Knee ligament injuries

Peer reviewed by Dr Krishna Vakharia, MRCGPLast updated by Dr Colin Tidy, MRCGPLast updated 16 Aug 2022

Meets Patient’s editorial guidelines

Medical Professionals

Professional Reference articles are designed for health professionals to use. They are written by UK doctors and based on research evidence, UK and European Guidelines. You may find the Knee ligament injuries article more useful, or one of our other health articles.

In this article:

Continue reading below

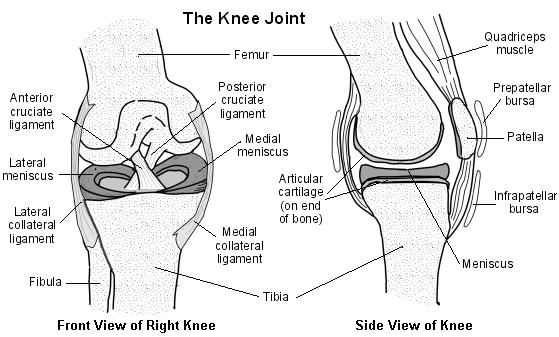

Anatomy of the knee

Cross-section diagram of the knee

Stability to the tibiofemoral joint is provided by several ligaments:

Medial collateral ligament (MCL) - prevents lateral movement of the tibia on the femur when valgus (away from the midline) stress is placed on the knee. Runs between the medial epicondyle of the femur and the anteromedial aspect of the tibia. Also has a deep attachment to the medial meniscus.

Lateral collateral ligament (LCL) - prevents medial movement of the tibia on the femur when varus (towards the midline) stress is placed on the knee. Runs between the lateral epicondyle of the femur and the head of the fibula. Also known as the fibular collateral ligament (FCL).

Anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) - controls rotational movement and prevents forward movement of the tibia in relation to the femur. Runs between attachments on the front (hence anterior cruciate) of the tibial plateau and the posterolateral aspect of the intercondylar notch of the femur.

Posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) - prevents forward sliding of the femur in relation to the tibial plateau. Runs between attachments on the posterior part (hence posterior cruciate) of the tibial plateau and the medial aspect of the intercondylar notch of the femur.

Knee ligament injuries

For guidance on examination of the knee, see also the separate Knee Pain article.

Any of the four ligaments of the knee may be injured, in isolation or with another associated injury. Ligament injuries can be graded according to the degree of damage:

Grade I: a few fibres are damaged or torn. This will usually heal naturally. It is often referred to as a sprain.

Grade II: more fibres are torn but the ligament is still intact. This may be referred to as a severe sprain.

Grade III: the ligament is completely disrupted. The knee joint is unstable and surgery may be indicated.

General management of knee ligament injuries

Following acute injury, rapid onset of a large tense effusion over 0-2 hours is suggestive of a ligamentous injury, particularly the ACL, or a fracture or dislocation. See also the separate Meniscal Tears and Other Knee Cartilage Injuries and Tibial and Fibular Fractures (including Horse Rider's Knee) articles.

Management aims are to manage pain, minimise knee swelling, maintain range of movement and quadriceps activation and arrange appropriate referral.

Physiotherapy is an integral part of the management of knee injuries, both in conservative and in surgical settings.1

In young adults, knee injury increases the risk of future diagnosed knee osteoarthritis about six-fold with highest risks found after cruciate ligament injury, meniscal tear and intra-articular fracture.2

X-ray assessment for knee injuries3

The Ottawa Knee Rules can be used to decide whether an X-ray is indicated. An X-ray should be performed if any of the following are present:

Inability to bear weight, both immediately and during the consultation, for four steps (inability to transfer weight twice on to each lower limb regardless of limping).

Inability to flex the knee to 90°.

Tenderness of the head of the fibula.

Isolated tenderness of the patella (no bone tenderness of the knee other than the patella).

Age 55 years or older.

Either offer an X-ray of the knee or offer referral to the A&E department for an X-ray (depending on availability of X-ray). In addition, offer an X-ray of the knee if knee swelling occurs following acute trauma.

Continue reading below

Medial collateral ligament4

The MCL is composed of superficial and deep portions:

Superficial MCL - anatomically this is the middle layer of the medial compartment. The proximal attachment is the posterior aspect of medial femoral condyle and the distal attachment is to the metaphyseal region of the tibia. Its function is to provide primary restraint to valgus stress at the knee.

Deep MCL - this is the deep layer of the medial compartment, which in many cases will be separated from the superficial MCL. It inserts directly into the edge of the tibial plateau and meniscus.

The mechanism of injury is usually a direct blow to the lateral aspect of the knee or a twisting injury.3 It will often occur in association with cruciate and meniscal injuries.

MCL assessment

See also the separate Knee Pain article.

The valgus stress test

The valgus stress test is performed with the hip abducted and the knee at 30° of flexion.

This test is performed to measure the amount of joint-line opening of the medial compartment which could indicate an MCL complex injury; also, to look for potential rotation of the tibia on the distal femur.

The leg is placed over the edge of the table and the examiner places his/her thigh against the patient's thigh to stabilise it.

The fingers of one hand are placed directly over the joint line to feel for the amount of joint-line opening that occurs when the other hand creates valgus stress by pressure on the anterior aspect of the ankle.

When proficient, the amount of joint-line opening can be quantified by the examiner to between 0-5 mm, 5-10 mm, and greater than 1 cm. This would indicate either a mild, moderate, or complete tear of the MCL complex.

The clinical findings may be subtle even with complete injury.

Radiographic assessment

X-ray: look for the Pellegrini-Stieda phenomenon - with chronic injury it is common to see calcification at the origin of the MCL.5

MRI: Any concomitant meniscal tear should also be visible.

MCL injury treatment and management

General points

PRICER (Protect, Rest, Ice, Compression, Elevation, Rehabilitation) and non-weight-bearing restriction with the use of crutches (often only required for a few days) are recommended.

Bracing and non-weight-bearing may be sufficient for mild injury.

Surgical

Optimum healing of the MCL occurs when the torn ends are in contact. Maturation of the scar occurs from six weeks to up to one year. The maturing scar tissue has only about 60% of the strength of the normal MCL.

The surgical plan depends on whether the injury is proximal, mid-substance, or distal. The knee should be held flexed at 30° and held in varus when the ligament is re-attached.

Complications

Early operative treatment of combined ACL and MCL injuries can lead to restriction of movement and slow recovery of the quadriceps muscle. Aggressive physiotherapy may be required and non-operative treatment may be preferred.6

Prevention of MCL injury

Prophylactic knee bracing has shown promise in preventing injury to the MCL.7

Lateral collateral ligament8

This is the primary restraint to varus angulation. LCL also acts to resist internal rotation forces.9

The mechanism of injury may be a direct blow to the medial aspect of the knee, which is rare due to the protective effects of the other knee, but may also be due to a varus stress such as a runner twisting on to the side of the planted foot.3 A case of isolated rupture of the LCL has been reported to have occurred during yoga practice.10

LCL assessment

See also the separate Knee Pain article.

Varus stress testing

The varus stress test is slightly more difficult to perform than the valgus test because the table begins to get in the way of performing the test correctly.

The patient's thigh is placed slightly more away from the table and one hand is placed with the thumb stabilising the lower extremity and the fingers or thumb placed directly over the lateral joint line.

In this position, the amount of joint-line opening that occurs can be palpated.

It is important that this hand also serve to stabilise the extremity such that true amount of instability can be felt.

The other hand is placed over the patient's foot and is used to apply varus stress with the knee flexed at 30°.

Increased varus opening is assessed and compared with the normal contralateral knee. Mild (0-5 mm), moderate (5-10 mm), or severe (>10 mm) lateral compartment opening, compared with the normal knee, is usually indicative of at least a posterolateral knee injury and potentially an ACL and/or PCL injury.

LCL injury treatment and management

General points

PRICER and non-weight-bearing restriction with the use of crutches are recommended.

Knee bracing with the knee locked in full extension for 4-6 weeks with weight bearing as tolerated. Active and passive range of movement exercises in the prone position are essential to prevent stiffness.

Surgical

Achilles allograft reconstruction may be used with acute grade III and chronic posterolateral injury. The main goal is to create a restraint for external rotation. A return to full weight-bearing gait should be gradual over the course of four weeks.

Continue reading below

Anterior cruciate ligament11

ACL tears most often occur in younger patients during football and basketball; in older patients, they occur most often from skiing injuries.12 Substantial anterior tibial shear forces that stress the ACL are produced from quadriceps contraction, especially in 0-30° of extension.

Typically, the ACL is torn in a non-contact deceleration or change of direction with a fixed foot that produces a valgus twisting injury. This usually occurs when the athlete lands on the leg and quickly pivots in the opposite direction. Meniscal tears are often associated with ACL injury. See the separate Meniscal Tears and Other Knee Cartilage Injuries article.

Mechanisms reported as possibly able to disrupt the ACL with minimal injury to other structures are:

Hyperextension.

Marked internal rotation of the tibia on the femur.

Pure deceleration.

ACL assessment

See also the separate Knee Pain article.

The anterior drawer test

Flex the knee to 90°.

Hold the position by sitting on the patient's foot.

Ensure that the hamstring muscles are relaxed.

With both hands, grasp below the knee and pull the tibia forward.

Compare the degree of movement with the other side.

Excessive movement may indicate ACL disruption.

Lachman's test

Flex the knee to 15-20°.

Hold the lower thigh in one hand and the upper tibia in the other.

Push the thigh in one direction and pull the tibia in the other.

Reverse the direction, pushing the tibia and pulling the thigh, looking for increased movement or laxity between the tibia and the femur.

Pivot shift test

Hold the patient's heel with one hand.

Internally rotate the foot and the tibia and, at the same time, apply an abduction (valgus) force at the knee.

Flex the knee from 0° to 30° whilst applying this force and still holding the foot and tibia in internal rotation.

Try to detect any palpable or visible reduction between the femur and the tibia.

Radiographic assessment

MRI of the knee is most commonly indicated in patients with suspected injuries of the menisci and of the cruciate ligaments.13 Plain radiographs have little value unless there has been an injury due to direct impact. In teaching centres where dedicated musculoskeletal radiologists report on images, diagnostic accuracy of 90% can be achieved for damage to the medial meniscus and ACL, slightly less for the lateral meniscus and slightly more for the PCL.

ACL injury treatment and management

General points

Surgical treatment is recommended for young and athletic patients as it can also reduce the risk of further relevant injuries of the meniscus and cartilage.

However, some (if, for example, they are not highly active or athletic or are minimally symptomatic) may choose conservative management. Management aims are to manage pain, minimise knee swelling, maintain range of movement and quadriceps activation and arrange appropriate referral.

In conservative management, after initial control of pain and effusion (using the PRICER method), hamstring and quadriceps activation/disinhibition and protected weight bearing in a hinged brace should be recommended. As swelling and pain slowly resolve, the range of movement should return to normal, or nearly normal, parameters. Exercises should be advised that take place in an anterior/posterior plane - eg, stationary cycling.

Surgical

Each patient should be assessed individually with regards to the type and frequency of physical activity and the degree of laxity at presentation. In some circumstances primary reconstruction may be considered once the knee has settled, there is no swelling and a full range of movement has been restored. It is important to emphasise that individual patient factors will guide the decision on whether to reconstruct surgically.14

With a complete rupture, where no local healing response is detectable at the injury site, a graft must be used to replace the ACL. There are four options used. The first three types are autografts using the central one third of the patellar ligament or the quadriceps tendon. The fourth type of graft is a cadaveric allograft.

A Cochrane review has found low-quality evidence that surgical intervention followed by structured rehabilitation was no better than structured rehabilitation alone in patient-reported outcomes of knee function at two and five years following injury.15

Complications

Early surgery may be associated with arthrofibrosis.

Prognosis

Surgery does not guarantee a return to previous level of sporting activity. The risk of a second ACL injury is high, especially in the short term. In the long term there is a significant risk of osteoarthritis, regardless of surgical intervention; this is even higher if revision surgery is required.16

Posterior cruciate ligament17

The PCL provides 95% of the total restraining force to straight posterior displacement of the tibia relative to the femur.18 Its secondary action includes resistance to varus, valgus and external rotation.

Hyperflexion is the most common mechanism for an isolated PCL injury typically from a direct blow to the proximal tibia with the knee in flexion (eg, from a fall on to a flexed knee or where the proximal tibia hits the dashboard in an accident).3

Structural damage to the PCL occurs in more than one third of trauma patients experiencing an acute knee injury with haemarthrosis.19

Isolated and combined PCL injuries are associated with severe limitations in daily, professional, and sports activities, as well as with devastating long-term effects for the knee joint.20

PCL assessment

See also separate Knee Pain article.

Associated injuries include ACL and collateral ligament injury (knee dislocation) and tibial plateau rim fractures. Any assessment should consider these.

The pain, degree of swelling and disability associated with ACL and MCL injuries are often missing from the patient's history. Many are able to walk with normal gait immediately after the injury. The soft endpoint of the posterior drawer test is firm by 2-3 weeks after injury.

Posterior drawer test

This is the most sensitive test for diagnosis of a PCL tear (sensitivity 90%, specificity 98%).21

Perform the same examination as the anterior drawer test but pushing backwards in relation to the tibia instead of pulling forwards.

Compare the degree of movement with the other side.

Posterior sag test

Flex both knees to 90°.

Look at the position of the tibia in relation to the femur.

If there is rupture of the PCL, the position will be relatively posterior.

Radiographic assessment

MRI assessment can help in the assessment of damage but is less accurate in diagnosing chronic PCL tear21 .

PCL injury treatment and management

General points

Management aims are to manage pain, minimise knee swelling, maintain range of movement and quadriceps activation and arrange appropriate referral.

Use the PRICER method in addition to any other modalities incorporated by the physiotherapist to control pain and swelling - eg, electrical stimulation, cold whirlpool.

Patients with minimal injuries can bear weight as tolerated immediately, although some may require axillary crutches initially.

Axillary crutches and a long leg brace are recommended for more severe injury.

Rehabilitation should focus on quadriceps strengthening to counteract the effects of the hamstrings and gravity on displacing the tibia posteriorly.21

Surgical21

Indications for operative treatment include PCL avulsion fractures, tears associated with other knee ligament injuries and isolated tears that have failed conservative management.

Several different techniques may be used to reconstruct the PCL, so the treatment protocol is determined by the individual physician and the type of graft used in surgery. The gold standard treatment has not been identified.

Prognosis

Conservatively managed patients do well, with 80% of people in one study reporting satisfactory knee function and the majority returning to sport after non-operative treatment with a six-year follow-up.21

However, PCL ruptures may lead to chronic patellofemoral, as well as medial compartment, arthrosis. The long-term consequences of a completely ruptured PCL are unknown.

Further reading and references

- Sprains and strains; NICE CKS, April 2020 (UK access only)

- Scotney B; Sports knee injuries - assessment and management. Aust Fam Physician. 2010 Jan-Feb;39(1-2):30-4.

- Snoeker B, Turkiewicz A, Magnusson K, et al; Risk of knee osteoarthritis after different types of knee injuries in young adults: a population-based cohort study. Br J Sports Med. 2020 Jun;54(12):725-730. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2019-100959. Epub 2019 Dec 11.

- Knee pain - assessment; NICE CKS, Aug 2022 (UK access only)

- Andrews K, Lu A, Mckean L, et al; Review: Medial collateral ligament injuries. J Orthop. 2017 Aug 15;14(4):550-554. doi: 10.1016/j.jor.2017.07.017. eCollection 2017 Dec.

- Medial collateral ligament; Wheeless' Textbook of Orthopaedics

- Halinen J, Lindahl J, Hirvensalo E; Range of motion and quadriceps muscle power after early surgical treatment of acute combined anterior cruciate and grade-III medial collateral ligament injuries. A prospective randomized study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009 Jun;91(6):1305-12.

- Miyamoto RG, Bosco JA, Sherman OH; Treatment of medial collateral ligament injuries. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2009 Mar;17(3):152-61.

- Crespo B, James EW, Metsavaht L, et al; Injuries to posterolateral corner of the knee: a comprehensive review from anatomy to surgical treatment. Rev Bras Ortop. 2014 Dec 24;50(4):363-70. doi: 10.1016/j.rboe.2014.12.008. eCollection 2015 Jul-Aug.

- Lateral collateral ligament; Wheeless' Textbook of Orthopaedics

- Patel SC, Parker DA; Isolated rupture of the lateral collateral ligament during yoga practice: a case report. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong). 2008 Dec;16(3):378-80.

- Kohn L, Rembeck E, Rauch A; [Anterior cruciate ligament injury in adults : Diagnostics and treatment]. Orthopade. 2020 Nov;49(11):1013-1028. doi: 10.1007/s00132-020-03997-3.

- Anterior Cruciate Ligament; Wheeless' Textbook of Orthopaedics

- McNally EG; Magnetic resonance imaging of the knee. BMJ. 2002 Jul 20;325(7356):115-6.

- Levy BA, Krych AJ, Dahm DL, et al; Treating ACL injuries in young moderately active adults. BMJ. 2013 Feb 13;346:f963. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f963.

- Monk AP, Davies LJ, Hopewell S, et al; Surgical versus conservative interventions for treating anterior cruciate ligament injuries. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016 Apr 3;4:CD011166. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011166.pub2.

- Failla MJ, Arundale AJ, Logerstedt DS, et al; Controversies in knee rehabilitation: anterior cruciate ligament injury. Clin Sports Med. 2015 Apr;34(2):301-12. doi: 10.1016/j.csm.2014.12.008. Epub 2015 Feb 27.

- Pache S, Aman ZS, Kennedy M, et al; Posterior Cruciate Ligament: Current Concepts Review. Arch Bone Jt Surg. 2018 Jan;6(1):8-18.

- Posterior Cruciate Ligament; Wheeless' Textbook of Orthopaedics

- Winkler PW, Zsidai B, Wagala NN, et al; Evolving evidence in the treatment of primary and recurrent posterior cruciate ligament injuries, part 1: anatomy, biomechanics and diagnostics. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2021 Mar;29(3):672-681. doi: 10.1007/s00167-020-06357-y. Epub 2020 Nov 17.

- Winkler PW, Zsidai B, Wagala NN, et al; Evolving evidence in the treatment of primary and recurrent posterior cruciate ligament injuries, part 2: surgical techniques, outcomes and rehabilitation. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2021 Mar;29(3):682-693. doi: 10.1007/s00167-020-06337-2. Epub 2020 Oct 30.

- Montgomery SR, Johnson JS, McAllister DR, et al; Surgical management of PCL injuries: indications, techniques, and outcomes. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2013 Jun;6(2):115-23. doi: 10.1007/s12178-013-9162-2.

Article History

The information on this page is written and peer reviewed by qualified clinicians.

Next review due: 15 Aug 2027

16 Aug 2022 | Latest version

Feeling unwell?

Assess your symptoms online for free