Peripheral oedema

Peer reviewed by Dr Laurence KnottLast updated by Dr Colin Tidy, MRCGPLast updated 14 Oct 2021

Meets Patient’s editorial guidelines

Medical Professionals

Professional Reference articles are designed for health professionals to use. They are written by UK doctors and based on research evidence, UK and European Guidelines. You may find the Oedema article more useful, or one of our other health articles.

In this article:

Continue reading below

What is peripheral oedema?

Oedema is an accumulation of interstitial fluid. The volume of fluid in the interstitial space is normally kept constant at around 20% of body weight1 . Normally leakage from capillaries and lymphatic drainage keep this in balance. However, a number of different pathological processes can disturb the balance, causing an excess of fluid to collect. This may occur as a result of increased plasma volume, reduced plasma oncotic pressure, an increase in permeability or hydrostatic pressure of capillaries, or obstruction to lymphatic drainage.

Oedema is referred to as 'pitting' when after pressing on the affected skin, an indentation remains after the source of pressure has been removed. (For example, if you press gently on oedematous skin with your finger, then stop doing so, you can still see and feel the finger-shaped dent left behind.) This is the classic type of oedema caused by fluid accumulation. Non-pitting oedema occurs in conditions such as lymphoedema, myxoedema and lipoedema.

Peripheral oedema causes2

Pitting-dependent oedema

This is oedema of the ankle if mobile, sacral when bed-bound.

Immobility:

Increased fluid pressure from venous stasis.

Varicose veins.

Obesity:

Increased fluid pressure from sodium and water retention; should not to be confused with non-pitting lymphoedema.

Cardiac:

Increased fluid pressure: right heart failure, constrictive pericarditis.

Drugs:

Increased fluid pressure from sodium and water retention: calcium antagonists, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), prolonged steroid therapy, insulin.

Hepatic:

Decreased oncotic pressure due to hypoalbuminaemia. Also increased capillary permeability from systemic venous hypertension.

Renal:

Decreased oncotic pressure from protein loss, and increased fluid pressure from sodium and water retention: acute nephritic syndrome, nephrotic syndrome.

Gastrointestinal:

Decreased oncotic pressure: starvation, malnutrition, malabsorption, protein-losing enteropathy (eg, Crohn's disease, ulcerative colitis, tumours of stomach and colon, coeliac disease and other intestinal allergies).

Obstructive sleep apnoea:

Increased capillary hydrostatic pressure due to pulmonary hypertension.

Pregnancy:

Increased fluid pressure both from sodium and water retention and venous stasis from pelvic obstruction.

High-altitude illness:

Oedema of face, hands and ankles may occur. Cerebral and pulmonary oedema, however, are usually of greater concern if disease progresses.

Idiopathic oedema:

Associated with cyclical high lymph volume overload, or dynamic insufficiency: usually in a woman aged 20-40 years.

Variable and not related to menstrual periods.

Diagnosis is based on the exclusion of other causes of oedema.

Post-thrombotic syndrome:

Late complication of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) which occurs in up to two thirds of patients.

May present with pain, oedema, hyperpigmentation, and even skin ulceration.

May result from remaining venous obstructions, from reflux, or both.

Rate of reflux is highest during the 6-12 months after an acute DVT.

It may be temporary and self-limiting or not resolve, and persist at variable severity.

Pitting localised limb oedema

Compression of large veins by tumour or lymph nodes.

Following hip replacement or knee replacement.

Chronic venous insufficiency. May be unilateral or bilateral. Usually unilateral predominance.

Local infection, trauma (including burns, which may also cause generalised oedema because of protein loss), animal bites or stings.

Non-pitting lower-limb oedema

Hypothyroidism (mucopolysaccharide deposition).

Lymphoedema:

Blocked lymph channels: surgical damage, radiation, malignant infiltration, infectious (eg, filariasis), congenital (eg, Milroy's disease).

Lipoedema.

Allergy:

Increased capillary permeability: angio-oedema.

Continue reading below

Peripheral oedema symptoms2

Assessment should include:

Duration: swelling due to venous insufficiency is usually a long-standing problem.

Distribution of oedema:

Dependent oedema in an otherwise well patient suggests a benign cause such as immobility or varicose veins.

Pulmonary and ankle oedema are typical of cardiac failure.

Hands and face, which is most marked after lying down, occurs in hypoproteinaemia.

Ascites in liver failure, nephrotic syndrome, protein malnutrition.

Unilateral swelling, particularly of the calf, suggests a DVT.

Oedema in angio-oedema is mainly restricted to the face and lips, although any part of the body may be affected.

Hydroceles: fluid often accumulates in the scrotal sac - eg, in nephrotic syndrome.

Pitting-dependent oedema will become sacral if bed-bound.

Associated symptoms: breathlessness of recent onset may be due to cardiac failure, anaemia, lung cancer or pleural effusions (eg, from nephrotic syndrome).

Past history: coronary heart disease, chronic lung disease, DVT (past history could lead to venous insufficiency).

Medication.

Examination is directed towards assessment of the cause of oedema and therefore a full assessment including the cardiovascular system and abdomen is required.

Unilateral ankle oedema should raise suspicion of a DVT but oedema may be bilateral in inferior vein obstruction and, in cases of bilateral oedema, one side may be more affected and therefore more obvious than the other.

Peripheral oedema

By James Heilman, MD (own work) via Wikimedia Commons

Investigations2

A thorough history and examination along with a urine dipstick test will usually be sufficient to establish the cause, but the following may be required if clinical findings suggest:

Urine testing: (a combination of profuse proteinuria and oedema, with hypoalbuminaemia confirmed on blood testing, is pathognomonic of nephrotic syndrome).

Haemoglobin (anaemia may be a cause or aggravating factor of heart failure).

Renal function and electrolytes (renal disease such as acute kidney injury, chronic kidney disease, nephrotic syndrome, nephritic syndrome, etc).

LFTs (liver failure; may show hypoproteinaemia in cirrhosis, nephrotic syndrome, protein-losing enteropathy).

TFTs (for hypothyroidism).

Abdominal/pelvic ultrasound: will reveal, for example, pelvic tumour, ascites, liver metastases.

CXR: if heart failure or lung malignancy is suspected.

ECG: if heart failure is suspected.

D-dimer and duplex ultrasound scan where DVT is suspected. Duplex ultrasonography may also be useful for confirming chronic venous insufficiency.

Lymphoscintigraphy - the method of choice for evaluating lymphoedema3 .

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be indicated if ultrasonography is not conclusive and suspicion of DVT is high, or as an alternative to lymphoscintigraphy in evaluation of lymphoedema. It may also be required if tumours are found.

Continue reading below

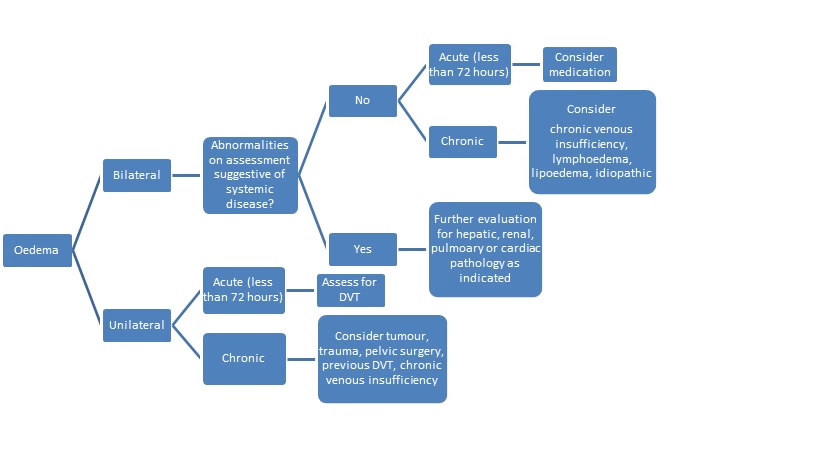

Algorithm4

The following algorithm may be helpful in assessing peripheral oedema.

Algorithm for peripheral oedema assessment.

Peripheral oedema treatment

Treatment is based on the cause.

Empirical treatment with diuretics is inappropriate in the absence of a clear diagnosis.

Further reading and references

- Scallan J, Huxley VH, Korthuis RJ; Capillary Fluid Exchange: Regulation, Functions, and Pathology. Chapter 4 Pathophysiology of Edema Formation. San Rafael (CA): Morgan & Claypool Life Sciences; 2010.

- Bromage D, Mayhew J, Sado D; Managing heart failure related peripheral oedema in primary care. BMJ. 2020 Jun 22;369:m2099. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m2099.

- Wiig H, Swartz MA; Interstitial fluid and lymph formation and transport: physiological regulation and roles in inflammation and cancer. Physiol Rev. 2012 Jul;92(3):1005-60. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00037.2011.

- Goyal A, Cusick AS, Bansal P; Peripheral Edema. StatPearls, 2021.

- Warren AG, Brorson H, Borud LJ, et al; Lymphedema: a comprehensive review. Ann Plast Surg. 2007 Oct;59(4):464-72.

- Trayes KP, Studdiford JS, Pickle S, et al; Edema: diagnosis and management. Am Fam Physician. 2013 Jul 15;88(2):102-10.

Article History

The information on this page is written and peer reviewed by qualified clinicians.

Next review due: 13 Oct 2026

14 Oct 2021 | Latest version

Feeling unwell?

Assess your symptoms online for free