Breast lumps and breast examination

Peer reviewed by Dr Colin Tidy, MRCGPLast updated by Dr Hayley Willacy, FRCGP Last updated 27 Sept 2021

Meets Patient’s editorial guidelines

Medical Professionals

Professional Reference articles are designed for health professionals to use. They are written by UK doctors and based on research evidence, UK and European Guidelines. You may find the Breast lumps article more useful, or one of our other health articles.

In this article:

The detection of a lump in the breast causes understandable fear of a cancer diagnosis. Careful examination will increase the chance of correct diagnosis. It is important that referrals are appropriate and that information and discussion accompany this assessment.

Continue reading below

Epidemiology

Breast cancer is the most common cancer in the UK, accounting for 15% of all new cancer cases (2017)1 . In females in the UK, breast cancer is the most common cancer (30% of all new female cancer cases). 99% of breast cancer cases in the UK are in females, and 1% are in males.

Age-standardised rates for White females with breast cancer range from 122.4 to 125.7 per 100,000. Rates for Asian females are significantly lower, ranging from 59.7 to 92.3 per 100,000, and the rates for Black females are also significantly lower, ranging from 68.8 to 107.9 per 100,000.

Risk factors for malignancy2 3

Previous history of breast cancer.

Family history of breast cancer in a first-degree relative. A number of genetic mutations are implicated. The BRCA1, BRCA2 and TP53 mutations carry very high risk but only around 5% of women diagnosed with breast cancer carry a relevant genetic mutation on their chromosomes. Between 6% and 19% of women will have a family history but this may be due to chance, shared environmental or lifestyle risk factors, or increased genetic susceptibility.

Risk increases with age. In Europe, ≤5% of cases present before the age of 35, ≤25% before the age of 504 . In the UK in 2015-2017, on average each year around a quarter of new cases (24%) were in people aged 75 and over1 .

Never having borne a child or having a first child after the age of 30.

Not having breastfed (breastfeeding is protective).

Early menarche and late menopause.

Radiation to chest (even quite small doses).

Being overweight.

High alcohol intake - may increase risk in a dose-related manner5

Breastfeeding and physical activity may reduce risk. Breast augmentation is not generally associated with increased risk. There are also concerns that implants may slow detection and therefore adversely affect survival6 .

Presentation

Presenting symptoms of breast cancer:

Breast lump. Most patients present having felt a lump - usually painless but may be painful in some.

Nipple change - eg, inversion, change in shape or a scaling rash.

Nipple discharge.

Bloodstained discharge from nipple - intraduct carcinoma may present in this way.

Skin contour changes.

Axillary lumps - lymph nodes.

Breast pain/mastalgia. Alone this is an uncommon presentation.

Symptoms of metastatic disease - bone pains/fractures, symptoms of lung, liver or brain metastases. (Unusual at presentation.)

Asymptomatic but picked up at routine mammography screen.

History

Organised screening, education programmes and improved consciousness of the female population have substantially changed the type of patients seen nowadays compared with a few decades ago and the neglected tumour is much rarer than it was. Occasionally, patients (usually elderly but not always) will still present with a fungating mass that has obviously been neglected for a long time.

Patients presenting with a lump in the breast will be aware of the possible diagnosis and will be very anxious. This should be taken into account when taking the history and discussing management.

Direct questions should include the following:

When was the lump first noticed?

Has it changed in size or in any other way? This includes a nipple becoming inverted.

Is there any discharge from the nipple?

Menstrual history. If she is premenopausal, when was her last menstrual period?

Any changes noted through the menstrual cycle?

Family history (including breast cancer, other cancers and other conditions).

Questions relating to the risk factors listed above.

Examination

In line with good practice and GMC guidance, explain to the patient what you intend to do and why7 . Obtain consent for the examination and document this. Offer a chaperone and document the discussion.

In the past, advice has been to use the examination to teach the patient self-examination. It may seem logical that regular self-examination should be beneficial but there is no evidence it reduces mortality, and may induce anxiety. Most authorities now suggest women should be "breast-aware" and report any change promptly rather than routinely self-examine3 .

Breast inspection

Inspect with the patient sitting and then with their hands raised above head.

A lump may be visible.

Look for:

Variations in breast size and contour.

Whether there is an inverted nipple (nipple retraction) and, if so, is it unilateral or bilateral?

Any oedema (may be slight).

Redness or retraction of the skin.

Dimpling of the skin (called peau d'orange and is like orange peel because of oedema of the skin. This has sinister significance as it is caused by lymphatic invasion, and therefore is due to an invasive underlying tumour, or an inflammatory breast cancer).

The next stage is palpation, and a systematic search pattern improves the rate of detection.

Technique for palpation of the breast8

There is no proven "best method" to examine the breast. Different people have different techniques and the following description is by no means the only approach.

Ask the patient to lie supine with their hands above their head. Examine from the clavicle medially to the mid-sternum, laterally to the mid-axillary line and to the inferior portion of the breast. Remember the axillary tail of breast tissue. Examine the axilla for palpable lymphadenopathy.

Examine with the hand flat to avoid pinching up tissue. Use the pads or palmar surfaces of the second, third and fourth fingers held together and moved in small circles.

Some advise beginning with light pressure and then repeating in the same area using medium and deep pressure before moving to the next section.

Three search patterns are generally used:

Radial spoke method (wedges of tissue examined starting at the periphery and working in towards the nipple in a radial pattern).

Concentric circle method, examining in expanding or contracting concentric circles.

Vertical strip method, which examines the breast in overlapping vertical strips moving across the chest.

If you have difficulty finding a discrete lump, ask the patient to demonstrate it for you.

A discrete mass should be described in terms of location, size, mobility and texture. Mobility includes whether attached to skin or underlying tissue.

Examine both breasts.

Support the patient's arm to palpate axillary nodes and then feel for supraclavicular and cervical nodes. Note the presence or absence of palpable regional nodes.

If there is a history of discharge from the nipple it is often easier to get the patient to demonstrate the discharge (rather than the doctor attempting to do so). If there is no such history, it is inappropriate to attempt to demonstrate a discharge.

It is also worth noting:

Breast examination should be thorough and take about three minutes each side.

It can be taught using silicone models.

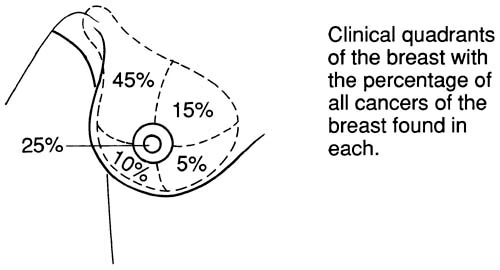

The diagram of frequency of malignancy by site in the breast:

Diagram of breast sections

If a lump is found, note size, consistency and whether it is attached to skin or underlying tissue.

Clinical features of palpable breast masses

Malignant breast masses | Benign breast masses |

Consistency: hard | Consistency: firm or rubbery |

Painless (90%) | Often painful (consistent with benign breast conditions) |

Irregular margins | Regular or smooth margins |

Fixation to skin or chest wall | Mobile and not fixed |

Skin dimpling may occur | Skin dimpling unlikely |

Discharge: bloody, unilateral | Discharge: no blood and bilateral discharge. Green or yellow colour |

Nipple retraction may be present | No nipple retraction |

Continue reading below

Appropriate referral9

The importance of minimising delay is consistently reported by patients in surveys to be very important and is recognised by professional consensus. Short delays are unlikely to affect the clinical course of a breast cancer. Longer delays are usually either due to patient delay or to the GP's failure to refer. Whilst there is evidence that earlier detection is associated with reduced mortality, there is controversial evidence about the effects of delays to treatment10 . GPs are advised by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) to convey optimism about the effectiveness of treatment and survival when referring people with suspected breast cancer.

Furthermore, the majority of palpable breast lumps are not breast cancer.

NICE guidance11

Refer people, using a suspected cancer pathway referral (for an appointment within two weeks) for breast cancer, if they are:

Aged 30 and over and have an unexplained breast lump with or without pain.

Aged 50 and over with any of the following symptoms in one nipple only:

Discharge.

Retraction.

Other changes of concern.

Consider a suspected cancer pathway referral (for an appointment within two weeks) for breast cancer in people:

With skin changes that suggest breast cancer.

Aged 30 and over with an unexplained lump in the axilla.

Consider non-urgent referral in people aged under 30 with an unexplained breast lump with or without pain.

Investigations

It is recommended that investigation prior to referral is not appropriate. Once seen in the breast clinic, investigation usually involves mammography and/or ultrasound, with biopsy if appropriate. For further details of investigation and diagnostic procedures, see the separate Breast Cancer article.

Further reading and references

- Suspected cancer; NICE Quality standard, June 2016 - last updated December 2017)

- Veitch D, Goossens R, Owen H, et al; Evaluation of conventional training in Clinical Breast Examination (CBE). Work. 2019;62(4):647-656. doi: 10.3233/WOR-192899.

- Ravi C, Rodrigues G; Accuracy of clinical examination of breast lumps in detecting malignancy: a retrospective study. Indian J Surg Oncol. 2012 Jun;3(2):154-7. doi: 10.1007/s13193-012-0151-5. Epub 2012 May 22.

- Breast cancer statistics; Cancer Research UK

- Familial breast cancer: classification, care and managing breast cancer and related risks in people with a family history of breast cancer; NICE Clinical Guideline (June 2013 - last updated November 2023).

- Breast cancer - managing FH: Summary; NICE CKS, December 2018 (UK access only)

- Primary breast cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up; ESMO (2015)

- Miller ER, Wilson C, Chapman J, et al; Connecting the dots between breast cancer, obesity and alcohol consumption in middle-aged women: ecological and case control studies. BMC Public Health. 2018 Apr 6;18(1):460. doi: 10.1186/s12889-018-5357-1.

- Sonden ECB, Sebuodegard S, Korvald C, et al; Cosmetic breast implants and breast cancer. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen. 2020 Feb 24;140(3). pii: 19-0266. doi: 10.4045/tidsskr.19.0266. Print 2020 Feb 25.

- Good Medical Practice - 2013; General Medical Council (last updated 2020).

- Thistlethwaite J, Stewart RA; Clinical breast examination for asymptomatic women - exploring the evidence. Aust Fam Physician. 2007 Mar;36(3):145-50.

- Breast cancer - recognition and referral; NICE CKS August 2020 (UK access only)

- Caplan L; Delay in breast cancer: implications for stage at diagnosis and survival. Front Public Health. 2014 Jul 29;2:87. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2014.00087. eCollection 2014.

- Suspected cancer: recognition and referral; NICE guideline (2015 - last updated October 2023)

Article History

The information on this page is written and peer reviewed by qualified clinicians.

Next review due: 26 Sept 2026

27 Sept 2021 | Latest version

Feeling unwell?

Assess your symptoms online for free