Slipped capital femoral epiphysis

SCFE

Peer reviewed by Dr Sarah Jarvis MBE, FRCGPLast updated by Dr Colin Tidy, MRCGPLast updated 29 Apr 2022

Meets Patient’s editorial guidelines

Medical Professionals

Professional Reference articles are designed for health professionals to use. They are written by UK doctors and based on research evidence, UK and European Guidelines. You may find one of our health articles more useful.

In this article:

Synonym: slipped upper femoral epiphysis

Continue reading below

What is slipped capital femoral epiphysis?

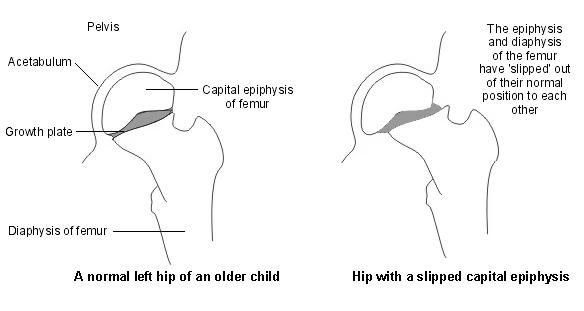

Often atraumatic or associated with a minor injury, slipped capital femoral epiphysis (SCFE) - sometimes called slipped upper femoral epiphysis - is one of the most common adolescent hip disorders and represents a unique type of instability of the proximal femoral growth plate. Characterised by a displacement of the proximal femoral epiphysis from the metaphysis, four separate clinical groups are seen:1

Pre-slip: wide epiphyseal line without slippage.

Acute form (10-15%): slippage occurs suddenly, normally spontaneously.

Acute-on-chronic: slippage occurs acutely where there is already existing chronic slip.

Chronic (85%): steadily progressive slippage (the most common form).

Hip with slipped capital epiphysis

The condition is also categorised as stable or unstable, which has greater prognostic value:

Stable (90% of cases): the patient is able to walk and osteonecrosis is very rare.

Unstable (10% of cases): the patient is unable to walk (even with crutches) and there is a 50% incidence of osteonecrosis.2

Radiographical classification is based on the degree or slip: mild (grade I), moderate (grade II) and severe (grade III).1

Diagnosis is often delayed - and this is associated with a worse prognosis.3

Slipped capital femoral epiphysis epidemiology4

SCFE is the most common hip disorder in adolescents, occurring in 10.8 per 100,000 children.

SCFE usually occurs in those aged 8 to 15 years of age and is one of the most commonly missed diagnoses in children.

The left hip is more commonly affected than the right; it is bilateral in 20-80% of cases.

It is 1.5 times more common in boys, although unstable slips appear to be at least as common in girls as in boys.

The incidence varies with racial group.

Incidence is rising; there is a trend to it occurring at a younger age and bilateral Slipped capital femoral epiphysis is increasing in frequency - all suspected to be related to increasing rates of childhood obesity.

Risk factors

SCFE is associated with obesity, growth spurts, and (occasionally) endocrine abnormalities such as hypothyroidism, growth hormone supplementation, hypogonadism, and panhypopituitarism.4

Mechanical: local trauma, obesity.

More than 80% of children diagnosed with slipped capital femoral epiphysis are obese.

Inflammatory conditions: neglected septic arthritis.

Endocrine:

Hypothyroidism, hypopituitarism, growth hormone deficiency, pseudohypoparathyroidism, vitamin D deficiency.

91% will be below the tenth percentile for height.5

Previous radiation of the pelvis, chemotherapy, renal osteodystrophy-induced bone dysplasia.

Contralateral slipped capital femoral epiphysis:2

There is a high incidence of slip in the contralateral hip (27% in one series).6

Controversy exists over whether or not a normal, asymptomatic hip should be fixed.

Scoring systems have been developed to stratify the risk; generally the younger the child is at presentation, the greater the risk of contralateral SCFE. Radiographic measurements of the angle of the growth plate to the neck of the femur are also used.

Weight loss to lower than 95% centile, following initial surgery, is associated with a lower risk of subsequent contralateral SCFE.6

Continue reading below

Slipped capital femoral epiphysis symptoms5

Discomfort in the hip, groin, medial thigh or knee (knee pain is referred from the hip joint) during walking, and a limp; pain is accentuated by running, jumping, or pivoting activities:

Knee pain due to referred pain from the hip is present in 15-50% of people with slipped capital femoral epiphysis.

Pre-slip: slight discomfort or found on X-ray.

Acute:

Presents within three weeks of onset of symptoms

Severe pain such that the child is unable to walk or stand.

Alterations in gait, including a limp on the affected side, external rotation of the leg and trunk shift.

Hip motion is limited, especially internal rotation and abduction, due to pain.

Obligate external hip rotation, Drehmann's sign: demonstrated when the child is supine and the hip is passively flexed and then falls back into external rotation and abduction.

Acute-on-chronic: pain, limp and altered gait occurring for several months, suddenly becoming very painful.

Chronic:

Present more than three weeks after onset of symptoms.

Mild symptoms with the child able to walk with altered gait. In a significant number of cases knee pain is reported as the only symptom.

External rotation of the leg during walking. Range of motion of the hip shows reduced internal rotation with additional external rotation.

When flexed up, the hip tends to move in an externally rotated position - see Drehmann's sign, above.

Mild-to-moderate shortening of the affected leg.

Atrophy of the thigh muscle may be noted.

Differential diagnosis7

Other causes of hip pain - for example:

Acute transient synovitis (irritable hip).

Continue reading below

Investigations4

Anteroposterior and 'frog-leg' lateral X-rays show widening of epiphyseal line or displacement of the femoral head.

Earliest findings include globular swelling of the joint capsule, irregular widening of the epiphyseal line and decalcification of the epiphyseal border of the metaphysis.

Epiphysis normally extends slightly cephalad to the upper border of the femoral neck.

Small amounts of slippage can be detected by the epiphyseal edge becoming flush with the superior border of the neck.

Sometimes, however, the only evidence of epiphyseal injury is slight widening of the growth plate.

Ultrasound can detect the presence of an effusion but is rarely indicated.

CT may be indicated if complex surgery is planned.5

Slipped capital femoral epiphysis treatment and management4 8

Avoid moving or rotating the leg. The patient should not be allowed to walk.

Provide analgesia and immediate orthopaedic referral if the diagnosis is suspected.

Closed reduction and hip spica casting are no longer used; they are more harmful than symptomatic or no treatment.5

Although surgery remains the standard treatment, the management of slipped capital femoral epiphysis remains controversial - a Cochrane review is currently assessing the outcome of the different surgical techniques, as well as non-operative treatments.1

Surgery2

The short-term goal of surgery is to prevent further progression of the slip and the longer-term goal is to prevent femoroacetabular impingement (FAI); residual abnormal morphology of the proximal femur is thought to be the cause of labral and cartilage damage leading to osteoarthritis of the hip.

Single in situ centre-to-centre screw fixation across the growth plate (pinning in situ) under fluoroscopic control is accepted as the most effective treatment for a stable slip:

It is minimally invasive requiring only a small incision on the thigh.

It is the most common treatment in all situations, stable and unstable, regardless of degree of deformity.5

In one series, excellent to good results were shown in 95% of mild slips, 91% of moderate slips and 86% of severe slips.

Arthrogram-assisted pinning may improve screw placement, particularly when fluoroscopic imaging is difficult due to obesity.

Open reduction:9

Most involve an osteotomy of the femoral neck, which has previously been reserved for treatment of severe deformities after the patient has stopped growing; however, it is increasingly used acutely in less severe cases to reduce the risk of FAI.2

Sometimes involves a surgical hip dislocation to create an extended retinacular flap to protect the blood supply to the femoral neck.

Routine use of open reduction is not recommended and it remains under evaluation.

It may reduce the rate of avascular necrosis (AVN) in unstable slipped capital femoral epiphysis.

Complications4 10

Chondrolysis (degeneration of the articular cartilage):5

Patients present with global loss of motion and pain.

Seen in 1.5% of slips treated with percutaneous in situ fixation.

Highest rates occur following non-operative treatment.

Avascular necrosis (AVN) of the epiphysis:11

Strongly associated with instability: patients with unstable slips have a 9.4-fold greater increased risk of AVN.

Is a risk factor for early development of severe osteoarthritis of the hip.

Occurs in 10-25% of cases and is associated with attempts to reduce a displaced epiphysis before treatment and with osteotomy of the femoral neck.

It is not clear whether early stabilisation (within 24 hours) reduces the risk of AVN; it may increase the risk.1

Recurrence or progression:5

More likely in non-idiopathic SCFE or following severe deformities.

True prevalence is not known.

Long-term effects of altered femoral head anatomy leading to osteoarthritis of the hip.

Prognosis10

The prognosis depends on the initial degree of epiphyseal slippage and on prompt recognition by the general practitioner.

The end result is much better when slip is mild or moderate.

With increasing displacement, complications increase.

Except for devastating complications, such as avascular necrosis of the femoral head and chondrolysis of the hip joint, the most critical factors that must be controlled in order to obtain better results are an early diagnosis of SCFE and prevention of femoroacetabular impingement.

Further reading and references

- Weight management: lifestyle services for overweight or obese children and young people; NICE Public health guideline, Oct 2013

- Johns K, Mabrouk A, Tavarez MM; Slipped Capital Femoral Epiphysis. StatPearls, Jan 2022.

- Herngren B, Stenmarker M, Vavruch L, et al; Slipped capital femoral epiphysis: a population-based study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2017 Jul 18;18(1):304. doi: 10.1186/s12891-017-1665-3.

- Baig MN, Glynn OA, Egan C; Slipped Upper Femoral Epiphysis: Are We Missing the Point? Cureus. 2018 Oct 1;10(10):e3394. doi: 10.7759/cureus.3394.

- Sattar JM Alshryda, Kai Tsang, Jalal Al-Shryda, John Blenkinsopp, Akinwanda Adedapo, Richard Montgomery, James Mason; Interventions for treating slipped upper femoral epiphysis (SUFE), Published Online: 28 FEB 2013 DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD010397

- Peck K, Herrera-Soto J; Slipped capital femoral epiphysis: what's new? Orthop Clin North Am. 2014 Jan;45(1):77-86. doi: 10.1016/j.ocl.2013.09.002.

- Weigall P, Vladusic S, Torode I; Slipped upper femoral epiphysis in children--delays to diagnosis. Aust Fam Physician. 2010 Mar;39(3):151-3.

- Peck DM, Voss LM, Voss TT; Slipped Capital Femoral Epiphysis: Diagnosis and Management. Am Fam Physician. 2017 Jun 15;95(12):779-784.

- Georgiadis AG, Zaltz I; Slipped capital femoral epiphysis: how to evaluate with a review and update of treatment. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2014 Dec;61(6):1119-35. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2014.08.001. Epub 2014 Sep 26.

- Nasreddine AY, Heyworth BE, Zurakowski D, et al; A reduction in body mass index lowers risk for bilateral slipped capital femoral epiphysis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2013 Jul;471(7):2137-44. doi: 10.1007/s11999-013-2811-3.

- Acute childhood limp; NICE CKS, September 2020 (UK access only).

- Aprato A, Conti A, Bertolo F, et al; Slipped capital femoral epiphysis: current management strategies. Orthop Res Rev. 2019 Mar 29;11:47-54. doi: 10.2147/ORR.S166735. eCollection 2019.

- Open reduction of slipped capital femoral epiphysis; NICE Interventional procedures guidance, January 2015

- Samelis PV, Papagrigorakis E, Konstantinou AL, et al; Factors Affecting Outcomes of Slipped Capital Femoral Epiphysis. Cureus. 2020 Feb 5;12(2):e6883. doi: 10.7759/cureus.6883.

- Novais EN, Millis MB; Slipped capital femoral epiphysis: prevalence, pathogenesis, and natural history. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2012 Dec;470(12):3432-8. doi: 10.1007/s11999-012-2452-y.

Article History

The information on this page is written and peer reviewed by qualified clinicians.

Next review due: 28 Apr 2027

29 Apr 2022 | Latest version

Feeling unwell?

Assess your symptoms online for free