Endometrial sampling

Peer reviewed by Dr Doug McKechnie, MRCGPLast updated by Dr Hayley Willacy, FRCGP Last updated 30 Jan 2023

Meets Patient’s editorial guidelines

Medical Professionals

Professional Reference articles are designed for health professionals to use. They are written by UK doctors and based on research evidence, UK and European Guidelines. You may find the Endometrial hyperplasia article more useful, or one of our other health articles.

In this article:

Continue reading below

What is endometrial sampling?

The endometrium is sampled when pathology, particularly endometrial cancer, is suspected; this may be when the patient experiences a change in her normal pattern of menstrual bleeding or when bleeding is unexpected - eg, after the menopause.

When a patient presents with any of these symptoms the GP should undertake a full pelvic examination, including speculum examination of the cervix.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines advise when to refer urgently in the UK:1

If the patient is aged over 55 with:

Unexplained bleeding more than 12 months after her last menstrual period, refer using urgent cancer referral.

Unexplained discharge:

If it is new; or

If she has thrombocytosis; or

If she reports haematuria -consider direct access ultrasound to assess the endometrium.

Visible haematuria and:

A low Hb; or

Thrombocytosis; or

Raised blood glucose - consider direct access ultrasound to assess the endometrium.

If the patient is aged under 55 with:

Unexplained bleeding more than 12 months after her last menstrual period, consider referral using urgent cancer referral.

Risk factors for endometrial cancer2

These include:

Obesity:

Diabetes (doubles the risk).5

Hypertension.

Insulin resistance and hyperinsulinaemia.6

Sedentary lifestyle.7

Longer exposure to oestrogen:

Anovulatory cycles - eg, polycystic ovary syndrome.8

Nulliparity.

Early menarche.

Late menopause.

Tamoxifen.

Unopposed oestrogen HRT.

Family history of endometrial or colonic cancer - Lynch syndrome.9

Continue reading below

Clinical scenarios

Postmenopausal woman with symptoms (vaginal bleeding)

Transvaginal ultrasound measurement of endometrial thickness has become a routine procedure and an initial investigation in most patients with abnormal uterine bleeding (see guidelines above).Greater than 5 mm endometrial thickness has been the standard threshold for the symptomatic postmenopausal patient having ultrasound scanning in the UK and the USA.10 There is some uncertainty regarding the optimal cutoff for endometrial thickness. Several meta-analyses that have used a cutoff measurement of 5 mm or less had a 96% sensitivity and a post-test probability of 2.5% for endometrial cancer in postmenopausal women.11 However, there is a false positive rate of over 70%.12 The British Gynaecological Cancer Society 2021 guidelines suggest a threshold of 4 mm.13 Greater thickness is associated with an increased risk of endometrial pathology - cancer, hyperplasia and polyps, and the thicker the endometrium, the greater the risk.

If a thickness of >4 or 5 mm is found, the next step is to obtain an endometrial sample for histology. This strategy is the most cost-effective for the UK where the prevalence of endometrial cancer is below 15%.14

If the endometrial sample is normal but the bleeding persists, further sampling is recommended.13

Asymptomatic postmenopausal women

When there is a coincidental finding of a thickened endometrium of greater than 4 mm, endometrial sampling is not necessary.13 15 However, if the endometrial thickness is >11 mm it is recommended that a biopsy should be taken.16 Decisions on further surveillance are made based on each individual's risk profile.

Pre-menopausal women

Pre-menopausal women with irregular bleeding, after history and examination, should be offered investigation according to NICE guidelines.17 This will be either hysteroscopy and endometrial sampling, or pelvic ultrasound. In the pre-menopausal patient, the timing of the ultrasound should be as close to the end of the bleeding period as possible. This should be when the endometrium is at its thinnest.

Endometrial biopsy

Introduced in the 1930s, originally using a narrow metal cannula with side opening with serrated edges and syringe attached for suction as the instrument was removed.

As the cannula was rotated during removal, a strip of endometrium was peeled off and sucked into the syringe. This caused significant cramping during removal.

Subsequently, the Vabra® curette was introduced, which required a vacuum source and also caused significant cramping.

Today the most widely used device is the disposable Pipelle® also known as Pipelle de Cornier®.

Can now be performed without prior cervical dilatation and can be undertaken as an outpatient procedure or in general practice.

Transcervical instillation of 5 mls 2% lidocaine can be used and has been shown to significantly reduce pain during endometrial sampling.18

Endometrial sampling in primary care

Studies have shown that endometrial sampling is possible and effective in general practice.19 20 The samples are taken by trained general practitioners and initial management of these patients is exclusively in primary care. Most patients are treated with the Mirena® intrauterine system. Pre-menopausal patients with abnormal uterine bleeding can be managed in general practice without referral to hospital if endometrial sampling is available to appropriately trained and supported GPs - GPs with Extended Roles.

Continue reading below

Pipelle® biopsy21

Pipelle® endometrial biopsy is a cost-effective and safe procedure that is well tolerated by patients.

Pipelle® is a flexible polypropylene suction cannula with an outer diameter of 3.1 mm. For comparison, this is significantly narrower than the diameter of a Mirena® intrauterine system insertion tube, which is 4.4mm.22

There is less pain and a lower risk of perforation with the Pipelle® than with the Novak® curette.23

In addition, the Pipelle® is more portable than the Novak® curette and the Vabra® aspirator, both of which require external suction.

A quantitative systematic review showed that, providing an adequate specimen is obtained, Pipelle® has a high positive predictive value. However, it also concluded that Pipelle® has a poor negative predictive value. Therefore if a woman is at high risk of endometrial carcinoma and her symptoms persist but her Pipelle® biopsy is normal, further evaluation is warranted.24

In postmenopausal women the inadequate sample rate has been reported as 31%.25

The Pipelle® is poor at detecting endometrial pathologies such as polyps and submucosal myomas.

Procedure

A sexual history and screening for sexually transmitted infections should be considered.

Bimanual examination to assess the uterus.

The cervix is then visualised.

A tenaculum is applied to the anterior lip of the cervix and is used to provide gentle traction whilst a sound is inserted though the cervical os. This minimises the risk of perforation.

Dilators may be required if there is difficulty in passing the sound.

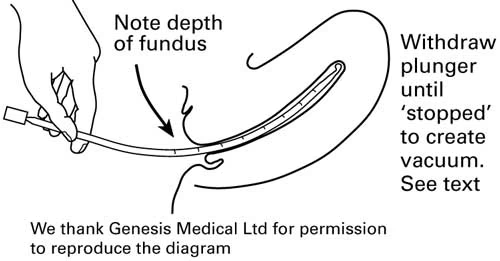

When the position and size of the uterine cavity have been assessed, the Pipelle® is inserted through the cervical os and advanced until gentle resistance is felt.

The inner piston of the device is then withdrawn to create suction and the endometrial sample is obtained by moving the Pipelle® up and down within the uterine cavity by approximately 2-3 cm but not beyond the cervical os.

Endometrial sampling

This procedure should be repeated at least four times and the device rotated 360° to ensure adequate coverage of the area.

The Pipelle® is then withdrawn from the cervical os and the endometrial sample expelled into a solution of formalin for transport to the laboratory.

Pipelle® endometrial sampling can also be combined with hysteroscopy.

Other devices include:

The Gravlee Jet Washer®.

The Mi-Mark® spiral sampler.

The Gynoscann® surface stripper (based on the intrauterine contraceptive device (IUCD) insertion principle).

The H Pipelle®.26

The Explora®.27

The Tao brush®.28

Vabra aspirator.29

SAP-1 sampler.29

Contra-indications

These include:

Pregnancy.

Acute vaginal or cervical infection.

Clotting disorders.

Risk of endocarditis is not a contra-indication and antibiotic prophylaxis is no longer recommended.30

Complications

These include:

Prolonged bleeding.

Infection.

Uterine perforation and post-procedure pain.

Dilatation and curettage

This has been the traditional technique for obtaining samples of endometrium for pathological examination. However, 'blind' dilatation and curettage (D&C) has been shown to miss significant amounts of pathology, including:

Endometrial polyps.

Intrauterine mucous fibroids.

Small areas of endometritis.

Hyperplasia or cancer.

Diagnostic curettage requires cervical dilatation to >8 mm and the use of a small sharp curette for systematic, thorough, gentle sampling of all parts of the uterine cavity, including the tubal osteal areas.

Fractional curettage uses endocervical curettage followed by endometrial curettage with two samples examined separately.

Endomyometrial resection biopsy

3-5 mm deep biopsy obtained with hystero-resectoscope loop.

This is used to identify adenomyosis or to investigate deep lesions of the endometrium.

It permanently removes a narrow strip of basal endometrium with underlying myometrium.

This usually heals well.

Further reading and references

- Suspected cancer: recognition and referral; NICE guideline (2015 - last updated October 2023)

- Fader AN, Arriba LN, Frasure HE, et al; Endometrial cancer and obesity: epidemiology, biomarkers, prevention and survivorship. Gynecol Oncol. 2009 Jul;114(1):121-7. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2009.03.039. Epub 2009 Apr 29.

- Calle EE, Rodriguez C, Walker-Thurmond K, et al; Overweight, obesity, and mortality from cancer in a prospectively studied cohort of U.S. adults. N Engl J Med. 2003 Apr 24;348(17):1625-38.

- Soliman PT, Bassett RL Jr, Wilson EB, et al; Limited public knowledge of obesity and endometrial cancer risk: what women know. Obstet Gynecol. 2008 Oct;112(4):835-42. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318187d022.

- Saed L, Varse F, Baradaran HR, et al; The effect of diabetes on the risk of endometrial Cancer: an updated a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Cancer. 2019 May 31;19(1):527. doi: 10.1186/s12885-019-5748-4.

- Nead KT, Sharp SJ, Thompson DJ, et al; Evidence of a Causal Association Between Insulinemia and Endometrial Cancer: A Mendelian Randomization Analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015 Jul 1;107(9). pii: djv178. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djv178. Print 2015 Sep.

- Hermelink R, Leitzmann MF, Markozannes G, et al; Sedentary behavior and cancer-an umbrella review and meta-analysis. Eur J Epidemiol. 2022 May;37(5):447-460. doi: 10.1007/s10654-022-00873-6. Epub 2022 May 25.

- Cooney LG, Dokras A; Beyond fertility: polycystic ovary syndrome and long-term health. Fertil Steril. 2018 Oct;110(5):794-809. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2018.08.021.

- Biller LH, Syngal S, Yurgelun MB; Recent advances in Lynch syndrome. Fam Cancer. 2019 Apr;18(2):211-219. doi: 10.1007/s10689-018-00117-1.

- Management of Endometrial Hyperplasia; RCOG/BSGE Joint Guideline (2016)

- Braun MM, Overbeek-Wager EA, Grumbo RJ; Diagnosis and Management of Endometrial Cancer. Am Fam Physician. 2016 Mar 15;93(6):468-74.

- Schramm A, Ebner F, Bauer E, et al; Value of endometrial thickness assessed by transvaginal ultrasound for the prediction of endometrial cancer in patients with postmenopausal bleeding. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2017 Aug;296(2):319-326. doi: 10.1007/s00404-017-4439-0. Epub 2017 Jun 20.

- British Gynaecological Cancer Society (BGCS) Uterine Cancer Guidelines: Recommendations for Practice; British Gynaecological Cancer Society (Nov 2021)

- Dijkhuizen FP, Mol BW, Brolmann HA, et al; Cost-effectiveness of the use of transvaginal sonography in the evaluation of postmenopausal bleeding. Maturitas. 2003 Aug 20;45(4):275-82. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5122(03)00152-x.

- Ghoubara A, Emovon E, Sundar S, et al; Thickened endometrium in asymptomatic postmenopausal women - determining an optimum threshold for prediction of atypical hyperplasia and cancer. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2018 Nov;38(8):1146-1149. doi: 10.1080/01443615.2018.1458081. Epub 2018 Jun 3.

- Wolfman W; No. 249-Asymptomatic Endometrial Thickening. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2018 May;40(5):e367-e377. doi: 10.1016/j.jogc.2018.03.005.

- Heavy menstrual bleeding: assessment and management; NICE Guideline (March 2018 - updated May 2021)

- Hui SK, Lee L, Ong C, et al; Intrauterine lignocaine as an anaesthetic during endometrial sampling: a randomised double-blind controlled trial. BJOG. 2006 Jan;113(1):53-7.

- Dickson JM, Delaney B, Connor ME; Primary care endometrial sampling for abnormal uterine bleeding: a pilot study. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care. 2017 Oct;43(4):296-301. doi: 10.1136/jfprhc-2017-101735. Epub 2017 Aug 19.

- Narice BF, Delaney B, Dickson JM; Endometrial sampling in low-risk patients with abnormal uterine bleeding: a systematic review and meta-synthesis. BMC Fam Pract. 2018 Jul 30;19(1):135. doi: 10.1186/s12875-018-0817-3.

- Terzic MM, Aimagambetova G, Terzic S, et al; Current role of Pipelle endometrial sampling in early diagnosis of endometrial cancer. Transl Cancer Res. 2020 Dec;9(12):7716-7724. doi: 10.21037/tcr.2020.04.20.

- Jaydess Levonorgestrel Intrauterine System - New Product Review; Clinical Effectiveness Unit of the Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare, 2014

- Hill GA, Herbert CM 3rd, Parker RA, et al; Comparison of late luteal phase endometrial biopsies using the Novak curette or PIPELLE endometrial suction curette. Obstet Gynecol. 1989 Mar;73(3 Pt 1):443-5.

- Clark TJ, Mann CH, Shah N, et al; Accuracy of outpatient endometrial biopsy in the diagnosis of endometrial cancer: a systematic quantitative review. BJOG. 2002 Mar;109(3):313-21.

- Abdelazim IA, Abdelrazak KM, Elbiaa AA, et al; Accuracy of endometrial sampling compared to conventional dilatation and curettage in women with abnormal uterine bleeding. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2015 May;291(5):1121-6. doi: 10.1007/s00404-014-3523-y. Epub 2014 Nov 4.

- Madari S, Al-Shabibi N, Papalampros P, et al; A randomised trial comparing the H Pipelle with the standard Pipelle for endometrial sampling at 'no-touch' (vaginoscopic) hysteroscopy. BJOG. 2009 Jan;116(1):32-7.

- Arafah MA, Cherkess Al-Rikabi A, Aljasser R, et al; Adequacy of the endometrial samples obtained by the uterine explora device and conventional dilatation and curettage: a comparative study. Int J Reprod Med. 2014;2014:578193. doi: 10.1155/2014/578193. Epub 2014 Jan 8.

- Williams AR, Brechin S, Porter AJ, et al; Factors affecting adequacy of Pipelle and Tao Brush endometrial sampling. BJOG. 2008 Jul;115(8):1028-36.

- Du J, Li Y, Lv S, et al; Endometrial sampling devices for early diagnosis of endometrial lesions. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2016 Dec;142(12):2515-2522. doi: 10.1007/s00432-016-2215-3. Epub 2016 Aug 11.

- Prophylaxis against infective endocarditis: Antimicrobial prophylaxis against infective endocarditis in adults and children undergoing interventional procedures; NICE Clinical Guideline (March 2008 - last updated July 2016)

Article History

The information on this page is written and peer reviewed by qualified clinicians.

Next review due: 4 Dec 2027

30 Jan 2023 | Latest version

Feeling unwell?

Assess your symptoms online for free