Bleeding disorders

Peer reviewed by Dr Adrian Bonsall, MBBSLast updated by Dr Jacqueline Payne, FRCGPLast updated 28 Feb 2017

Meets Patient’s editorial guidelines

- DownloadDownload

- Share

- Language

- Discussion

- Audio Version

This page has been archived.

It has not been reviewed recently and is not up to date. External links and references may no longer work.

Medical Professionals

Professional Reference articles are designed for health professionals to use. They are written by UK doctors and based on research evidence, UK and European Guidelines. You may find the Blood clotting tests article more useful, or one of our other health articles.

In this article:

Related synonyms: bleeding diathesis, clotting disorder, coagulation disorder, coagulopathy, haemostatic disorder

Bleeding disorders are usually taken to mean coagulopathies with reduced clotting of the blood but also encompass disorders characterised by abnormal platelet function or blood vessel walls that result in increased bleeding. Bleeding disorders may result from faults at many different levels in the coagulation process. They can range from severe and life-threatening conditions, such as haemophilia A, to much milder variants. Some bleeding symptoms (eg, bruising without obvious cause, nosebleeds and heavy menstrual bleeding) are quite common in the general population and there is phenotypical variation even among individuals with defined bleeding problems. Investigation of mild bleeding problems often fails to provide a diagnosis.1

Continue reading below

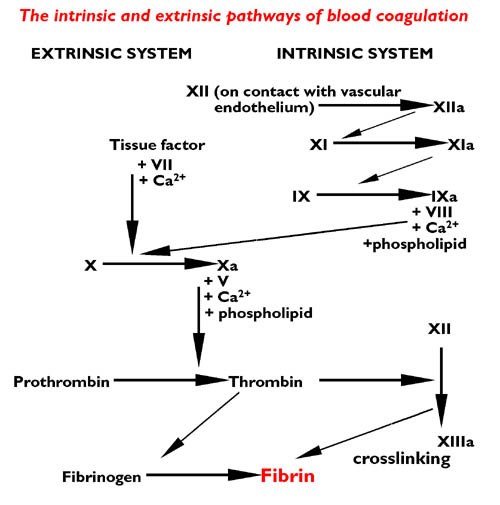

The coagulation cascade2

When a blood vessel is injured, a series of biochemical reactions is brought into play. This has been presented in the past as a coagulation 'cascade', describing a series of reactions necessary to achieve haemostasis by the development of a clot, stopping its formation at the right time and eventually facilitating clot dissolution when the vessel has healed. The scientific literature has moved towards the concept of a cell-based model which has more relevance to in vivo mechanisms (see below).

Nevertheless, the coagulation cascade is still useful in describing the sequence of events that occur in vitro and on which laboratory tests of coagulation are based.

Most of the proteins required for the cascade are produced by the liver as inactive precursors (zymogens) which are then modified into clotting factors. There are two routes for activation of the coagulation system: an intrinsic and an extrinsic pathway. The intrinsic pathway is activated by contact with collagen from damaged blood vessels (or indeed any negatively charged surface). The extrinsic pathway is activated by contact with tissue factor from the surface of extravascular cells.

Both routes end in a final common pathway - the proteolytic activation of thrombin and the cleaving of fibrinogen to form a fibrin clot. The intrinsic pathway is the main 'player' in this scenario, with the extrinsic pathway acting as an enhancer.

Coagulation

The cell-based model3

The original cascade proposed by McFarlane in 1964 has been developed over the ensuing decades. A newer model describes the complex formed by tissue factor and factor VII. These participate in the activation of factor IX, indicating that the intrinsic and extrinsic coagulation pathways are linked almost from the outset. The new cascade model identifies a role for endothelial cells and details the influence of host factors, including the role of inflammation in coagulation.

Three stages are identified in the cell-based model in which it is envisaged that most of the processes involved occur at the cell surface level:

Initiation - tissue injury exposes tissue factor (TF) to plasma. TF-expressing cells are found in the blood vessel walls but can also be induced in monocytes and TF-bearing microparticles derived from monocytes and platelets.

Amplification - small amounts of thrombin induce platelet activation and aggregation and promote activation of factors V, VIII and XI on platelet surfaces.

Propagation - this involves the formation of proteins (eg, tenase, prothrombinase) ending in the formation of the thrombin clot.

Platelets are identified as having three functions - control of thrombin generation, support of fibrin formation and regulation of fibrin clot retraction. It has been postulated that different populations of platelets, with distinct surface properties, are involved in these coagulant functions4.

Classification

Back to contentsBleeding disorders can be classified as either congenital or acquired:

Congenital bleeding disorders

Von Willebrand's disease (vWD) is the most common inherited bleeding disorder. Usually the condition is mild without spontaneous bleeding. It occurs equally in men and women and is caused by reduced production or abnormality of Von Willebrand's factor (vWF) that both promotes normal platelet function and stabilises factor VIII.

Haemophilia A (factor VIII deficiency) and haemophilia B (factor IX deficiency or Christmas' disease) are the most well-known congenital bleeding disorders as well as notable examples of X-linked genetic disease5.

Other inherited bleeding disorders affecting the coagulation pathway are much rarer and inherited in an autosomal recessive fashion; for example, prothrombin (factor II) deficiency is found in about 1 in 2 million individuals.

Platelet function disorders: rare autosomal recessive disorders affecting platelet membrane glycoproteins and causing abnormal platelet adhesion (eg, Bernard-Soulier syndrome), aggregation (eg, Glanzmann's thrombasthenia) or secretion6.

Acquired disorders7

Liver disease and cirrhosis cause reduced synthesis of clotting proteins and thrombocytopenia.

Vitamin K deficiency due to dietary deficiency, gastrointestinal malabsorption or absence of gut bacteria in infancy (vitamin K deficiency bleeding of the newborn)8.

Shock, sepsis or malignancy can all cause an increased bleeding tendency, often through the final common pathway of disseminated intravascular coagulopathy (DIC) where simultaneous microvascular thrombosis and generalised bleeding occur due to massive consumption of coagulation factors or damage to vessel walls (for example, in meningococcal septicaemia).

Renal disease: causes platelet dysfunction and reduced aggregation.

Autoimmune: circulating autoantibodies to coagulation factors (eg, in lymphoma and systemic lupus erythematosus) or to platelets (as in immune thrombocytopenic purpura).

Amyloidosis: where factor X deficiency occurs as well as hyperfibrinolysis and local infiltration of blood vessels.

Vitamin C deficiency leads to weakened collagen and blood vessel fragility but can also cause diffuse haemorrhage in surgical patients.9

Advanced age can be associated with fragile veins.10

Prolonged steroid use is reputed to be associated with hypercoagulability and increased bleeding tendency. However, one study found that this effect was likely to be of limited clinical consequence.11

Remember that some diseases can be associated with both bleeding and thrombosis - eg, polycythaemia vera and essential thrombocythaemia.12

Continue reading below

Presentation613

Back to contentsSymptoms

Bruising may be spontaneous or recurrent:

Large bruises on sun-exposed areas of limbs in the elderly are usually due to cumulative ultraviolet vessel damage to underlying elastin and are rarely significant.

Large bruises on the trunk are more indicative of a bleeding disorder.

Prolonged bleeding:

After minor cuts or abrasions.

Nosebleeds lasting >10 minutes despite adequate compression (especially in children).

Severe menorrhagia causing anaemia, with normal uterus.

Bleeding from gums without gingival disease and unrelated to brushing.

Following dental extraction.

Postpartum haemorrhage.

After injections or surgical procedures.

Also enquire regarding:

Current medication:

Including aspirin, clopidogrel, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, warfarin and other anticoagulants.

Complementary and alternative medicines - eg, garlic tablets, milk thistle.14

Remember drug interactions between warfarin and other medications that prolong the international normalised ratio (INR).

Family history of bleeding tendency.

Alcohol intake.

Other constitutional symptoms - eg, malaise, weight loss.

Past history of thrombosis (can be suggestive of thrombophilia).

Previous blood transfusions.

Renal or hepatic impairment.

Signs

Systemically look for:

Pallor.

Sepsis.

Haemodynamic status.

Lymphadenopathy or hepatosplenomegaly.

Check:

Skin, palate and gums for:

Bruising.

Petechia (non-blanching haemorrhagic spot <2 mm diameter).

Purpura (2-10 mm diameter).

Ecchymosis (>10 mm diameter).

Fundi for retinal haemorrhages.

Joints for haemarthrosis.

Rectal or vaginal examination may be appropriate.

Comparing coagulation factor and platelet defects15

| Coagulation factor defects | Platelet disorders and von Willebrand's disease |

Bruising on trunk and limbs | Large bruises | Small bruises |

Bleeding from cuts | Relatively slight | Profuse |

Nosebleeds | Uncommon | Common, frequently profuse and of long duration |

Gastrointestinal bleeding | Uncommon | Common |

Haematuria | Common | Rare |

Haemarthrosis | In severe haemophilia | Very rare |

Bleeding after surgery or dental extraction | Up to a day's delay before bleeding occurs | Immediate bleeding |

Investigations117

Back to contentsFBC, blood film and platelet count - may detect leukaemia, lymphoma, thrombocytopenia or abnormal platelets.

Consider checking U&Es to exclude uraemia causing a platelet disorder.

Consider LFTs to detect hepatic cause of acquired coagulation factor deficiency and alcohol-related damage.

Bone marrow biopsy.

A coagulation screen usually involves taking blood in a mixture of citrate, EDTA and clotted sample bottles. It includes:

Activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT):

This measures the intrinsic pathway (which includes factors I, II, V, VIII, IX, X, XI and XII) and the common pathway.

A plasma sample is used and the intrinsic pathway is activated by adding phospholipid, an activator such as kaolin (which acts as a negatively charged surface) and calcium ions. The formation of prothrombinase complexes on the surface of the phospholipid enables the formation of thrombin and a subsequent clot. The result is reported as the time in seconds for this reaction.

The test is used to assess the overall competence of the coagulation system, as a routine test to monitor heparin therapy and as a pre-operative screen for bleeding tendencies. It will also reveal possible coagulation factor deficiencies, as in haemophilia A and B.

Prothrombin time (PT):

This assesses the extrinsic and final common pathway of the coagulation cascade, thus can detect factor I, II, V, VII or X deficiency or the effects of warfarin.

It is performed by adding thromboplastin and calcium ions to a plasma sample. The time for clot formation is measured.

Prolonged time suggests the presence of an inhibitor to, or a deficiency of, one or more coagulation factors, the presence of warfarin, the existence of vitamin K deficiency or liver dysfunction.

The INR, used to monitor warfarin, is derived by comparing the patient's prothrombin time to that of a standardised sample.

Thrombin clotting time test:

This measures the rate of a patient's clot formation compared with a normal plasma control. The plasma is first depleted of platelets and a standard amount of thrombin added.

The test is used in the diagnosis of DIC and other conditions that can affect fibrinogen level, such as liver disease.

Thromboelastometry:

This is not generally part of the conventional screen but is increasingly recognised as important in the emergency situation18.

It can help to differentiate between surgical or traumatic blood loss and coagulopathy and its use can guide the use of haemostatic therapy.

If the above tests are all normal, the vast majority of common haemostatic disorders will have been excluded. However, if symptoms persist and/or there is a suggestion of family history, patients should be referred to a haematologist for further tests which may include:

The platelet function analyser (PFA), which has largely replaced the in vivo bleeding time test (see below), although it is not specific for, or predictive of, any particular disorder and its limitations need to be taken into account.1920

Bleeding time - this tests the interaction between the platelets and the vessel walls. A standardised spring-loaded lancet is used to make a small cut in the patient's forearm and the time for the bleeding to stop is then measured. The test is not useful as a screening test, as it has a high false positive result. It is sometimes used in the investigation of vWD, although it has been largely superseded by the PFA.

Fibrinogen - the level can be determined by immunological or functional assay. It is usually performed when APTT or PT screening tests are prolonged. The main disorders detected are afibrinogenaemia or hypofibrinogenaemia (due to absence or a low level of fibrinogen production) and dysfibrinogenaemia (due to a molecular alteration of fibrinogen, causing poor function). Differences in the level of fibrinogen measured by the two methods are suggestive of dysfibrinogenaemia.1

Specific factor assays - factors VIII or IX to determine severity of haemophilia; factor VIII and vWF in vWD.

Gene analysis looking for specific gene defects.

Haemostasis tests in bleeding disorders1

| Platelet count | Prothrombin time | Activated partial thromboplastin time | Bleeding time | Thrombin time | Additional tests |

Haemophilia A | Normal | Normal | Prolonged | Normal |

| Factor VIII low |

Haemophilia B | Normal | Normal | Prolonged | Normal |

| Factor IX low |

Von Willebrand's disease | Normal | Normal | Prolonged or normal | Prolonged |

| Von Willebrand's factor and factor VIII activity low and impaired ristocetin-induced platelet aggregation |

Liver disease | Low | Prolonged | Prolonged |

| Normal (rarely prolonged) |

|

Disseminated intravascular coagulopathy | Low | Prolonged | Prolonged |

| Grossly prolonged |

|

Massive transfusion | Low | Prolonged | Prolonged |

| Normal |

|

Oral anticoagulants | Normal | Grossly prolonged | Prolonged |

| Normal |

|

Heparin | Normal (rarely low) | Mildly prolonged | Prolonged |

| Prolonged |

|

Continue reading below

Management

Back to contentsManagement is dependent on the underlying condition - see separate Haemophilia A (Factor VIII Deficiency), Haemophilia B (Factor IX Deficiency) and Von Willebrand's Disease articles.

Whilst the sex-linked nature of haemophilia results in those affected being predominantly male, women are much more likely to present with mild bleeding disorders due to the demands of menstruation and childbirth. Menorrhagia can be tackled by standard means - see separate Menorrhagia article.

Prevention

Back to contentsThose with serious inherited bleeding disorders may want genetic counselling and prenatal diagnosis22.

Further reading and references

- The Haemophilia Society

- Guideline on the selection and use of therapeutic products to treat haemophilia and other hereditary bleeding disorders; United Kingdom Haemophilia Centre Doctors' Organisation (UKHCDO)

- Othman M, Chirinian Y, Brown C, et al; Functional characterization of a 13-bp deletion (c.-1522_-1510del13) in the promoter of the von Willebrand factor gene in type 1 von Willebrand disease. Blood. 2010 Nov 4;116(18):3645-52. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-12-261131. Epub 2010 Aug 9.

- Canadian Hemophilia Society

- Hayward CP; Diagnosis and management of mild bleeding disorders. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2005:423-8.

- Adams RL, Bird RJ; Review article: Coagulation cascade and therapeutics update: relevance to nephrology. Part 1: Overview of coagulation, thrombophilias and history of anticoagulants. Nephrology (Carlton). 2009 Aug;14(5):462-70. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1797.2009.01128.x.

- De Caterina R, Husted S, Wallentin L, et al; Anticoagulants in heart disease: current status and perspectives. Eur Heart J. 2007 Apr;28(7):880-913. Epub 2007 Apr 10.

- Heemskerk JW, Mattheij NJ, Cosemans JM; Platelet-based coagulation: different populations, different functions. J Thromb Haemost. 2013 Jan;11(1):2-16. doi: 10.1111/jth.12045.

- Franchini M, Mannucci PM; Past, present and future of hemophilia: a narrative review. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2012 May 2;7:24. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-7-24.

- Bolton-Maggs PH, Chalmers EA, Collins PW, et al; A review of inherited platelet disorders with guidelines for their management on behalf of the UKHCDO. Br J Haematol. 2006 Dec;135(5):603-33.

- van Herrewegen F, Meijers JC, Peters M, et al; Clinical practice: the bleeding child. Part II: disorders of secondary hemostasis and fibrinolysis. Eur J Pediatr. 2012 Feb;171(2):207-14. doi: 10.1007/s00431-011-1571-x. Epub 2011 Sep 17.

- Chalmers EA; Neonatal coagulation problems. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2004 Nov;89(6):F475-8.

- Blee TH, Cogbill TH, Lambert PJ; Hemorrhage associated with vitamin C deficiency in surgical patients. Surgery. 2002 Apr;131(4):408-12.

- Leibovitch I, Modjtahedi S, Duckwiler GR, et al; Lessons learned from difficult or unsuccessful cannulations of the superior ophthalmic vein in the treatment of cavernous sinus dural fistulas. Ophthalmology. 2006 Jul;113(7):1220-6.

- Turan A, Dalton JE, Turner PL, et al; Preoperative prolonged steroid use is not associated with intraoperative blood transfusion in noncardiac surgical patients. Anesthesiology. 2010 Aug;113(2):285-91. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181e6a195.

- Schafer AI; Molecular basis of the diagnosis and treatment of polycythemia vera and essential thrombocythemia. Blood. 2006 Jun 1;107(11):4214-22. Epub 2006 Feb 16.

- Tosetto A; The Role of Bleeding History and Clinical Markers for the Correct Diagnosis of VWD. Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis. 2013 Jul 12;5(1):e2013051. doi: 10.4084/MJHID.2013.051. Print 2013.

- Shakeel M, Trinidade A, McCluney N, et al; Complementary and alternative medicine in epistaxis: a point worth considering during the patient's history. Eur J Emerg Med. 2010 Feb;17(1):17-9. doi: 10.1097/MEJ.0b013e32832b1679.

- Karnath B; Easy Bruising and Bleeding in the Adult Patient, 2005.

- Federici AB; Clinical diagnosis of von Willebrand disease. Haemophilia. 2004 Oct;10 Suppl 4:169-76.

- Mumford AD, Ackroyd S, Alikhan R, et al; Guideline for the diagnosis and management of the rare coagulation disorders: a United Kingdom Haemophilia Centre Doctors' Organization guideline on behalf of the British Committee for Standards in Haematology. Br J Haematol. 2014 Nov;167(3):304-26. doi: 10.1111/bjh.13058. Epub 2014 Aug 6.

- Spahn DR, Bouillon B, Cerny V, et al; Management of bleeding and coagulopathy following major trauma: an updated European guideline. Crit Care. 2013 Apr 19;17(2):R76. doi: 10.1186/cc12685.

- Favaloro EJ; The Platelet Function Analyser (PFA)-100 and von Willebrand disease: a story well over 16 years in the making. Haemophilia. 2015 Sep;21(5):642-5. doi: 10.1111/hae.12710. Epub 2015 May 16.

- Naik S, Teruya J, Dietrich JE, et al; Utility of platelet function analyzer as a screening tool for the diagnosis of von Willebrand disease in adolescents with menorrhagia. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2013 Jul;60(7):1184-7. doi: 10.1002/pbc.24456. Epub 2013 Jan 17.

- Handbook of Diagnostic Hemostasis and Thrombosis Tests; University of Washington Department of Laboratory Medicine Reference Laboratory Services, 2005

- Street AM, Ljung R, Lavery SA; Management of carriers and babies with haemophilia. Haemophilia. 2008 Jul;14 Suppl 3:181-7.

Continue reading below

Article history

The information on this page is written and peer reviewed by qualified clinicians.

28 Feb 2017 | Latest version

Ask, share, connect.

Browse discussions, ask questions, and share experiences across hundreds of health topics.

Feeling unwell?

Assess your symptoms online for free