Psoriasis

Peer reviewed by Dr Rachel Hudson, MRCGPLast updated by Dr Doug McKechnie, MRCGPLast updated 26 Apr 2023

Meets Patient’s editorial guidelines

- DownloadDownload

- Share

- Language

- Discussion

- Audio Version

In this series:Guttate psoriasisPsoriatic arthritisNail psoriasis

Psoriasis is a long-term skin condition that can also affect the nails and joints. It tends to flare up from time to time. Treatment with various creams or ointments can often clear or reduce patches (plaques) of psoriasis.

Special light therapy and/or powerful medication are treatment options for severe cases where creams and ointments have not worked very well. People with psoriasis are more likely than usual to develop cardiovascular disease (heart disease and strokes).

In this article:

Video picks for Other skin problems

Continue reading below

What is psoriasis?

Psoriasis is a common skin condition where there is inflammation of the skin. It typically develops as patches (plaques) of red, scaly skin. Once you develop psoriasis it tends to come and go throughout life. A flare-up can occur at any time.

The frequency of flare-ups varies. There may be times when psoriasis clears for long spells. However, in some people the flare-ups occur often. Psoriasis is not due to an infection. You cannot pass it on to other people and it does not turn into cancer.

The severity of psoriasis varies greatly. In some people it is mild with a few small patches that develop and are barely noticeable. In others, there are many patches of varying size. In most people the severity is somewhere between these two extremes.

What is psoriasis?

What are the different types of psoriasis?

Back to contentsThere are different types of psoriasis. However, chronic plaque psoriasis (described below) is by far the most common and typical type.

The Primary Care Dermatology Society has published a 'Treatment pathway' - see Further Reading below. This has several pictures that may be useful, as well as a clear plan for treatment of the different areas and types of psoriasis. This includes often difficult to treat areas such as the face, the hands and the genital area.

Chronic plaque psoriasis

Elbow plaque psoriasis

© Haley Otman,CC BY 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

By Haley Otman, CC BY 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Between 8 and 9 out of 10 people with psoriasis have chronic plaque psoriasis. The rash is made up of red patches (plaques) on the skin. The picture shows typical plaques of psoriasis next to some normal skin. Each plaque usually looks pink or red with overlying flaky, silvery-white scales that feel rough. There is usually a sharp border between the edge of a plaque and normal skin.

The most common areas affected are over elbows, knees and the lower back. However, it may differ from person to person and appear anywhere on the skin, including:

Scalp psoriasis

This affects roughly half of people with chronic plaque psoriasis of the skin of their body. However, scalp psoriasis may occur alone in some people. It looks like severe dandruff. The whole scalp may be affected, or there may just be a few patches. If severe, it can lead to hair loss in some people.

Flexural psoriasis

Also known as inverse psoriasis. This is also a type of chronic plaque psoriasis but the affected skin looks slightly different - it is red and inflamed but the skin is smooth and does not have the rough scaling. It occurs in the creases of the skin (flexures) such as in the armpit, in the groin, under breasts and in skin folds.

The extent of the psoriasis can differ from person to person and can also vary from time to time in the same person. Many people have just a few small plaques of a centimetre or so when their psoriasis flares up. Others have a more widespread rash with large plaques of several centimetres across. Chronic plaque psoriasis can be itchy but it does not usually cause too much discomfort.

Nail psoriasis

About half of people with any type of psoriasis also get fingernail psoriasis. In some people toenails are also affected. Nail psoriasis may also occur alone without any skin rash. See the separate leaflet called Psoriatic Nail Disease for more details.

Pustular psoriasis

This is the second most common type of psoriasis. It usually just affects the palms of the hands and soles of the feet. (It is sometimes called palmoplantar pustulosis.) Affected skin develops crops of pustules, which are small fluid-filled spots. The pustules do not contain germs (bacteria) and are not infectious. The skin under and around the pustules is usually red and tender.

Rarely, a form of pustular psoriasis can affect skin apart from the palms and soles. This more widespread form is a more serious form of psoriasis and needs urgent treatment under the care of a skin specialist (a dermatologist).

Guttate (drop) psoriasis

This is a type of psoriasis where the trigger is known to be a germ (bacterium). It typically occurs following a sore throat. See the separate leaflet called Guttate Psoriasis for more details.

Erythrodermic psoriasis

This type of psoriasis is rare. It causes a widespread redness (erythema) of much of the skin surface, which is painful. Individual plaques of psoriasis cannot be seen because they have merged together.

There is still redness and scaling of the skin and the skin feels warm to touch. A person with erythrodermic psoriasis may also have a high temperature (fever). It is serious and needs urgent treatment and admission to hospital. It can interfere with your body's ability to control your temperature, and also causes lack of fluid in the body (dehydration).

Continue reading below

How common is psoriasis?

Back to contentsAbout 1 in 50 people develop psoriasis at some stage of their lives. It can first develop at any age but it most commonly starts between the ages of 15 and 30 years.

About 3 in 10 people with psoriasis have a close relative with the same problem. Also, one large study found that smokers (and ex-smokers for up to 20 years after giving up) have an increased risk of developing psoriasis compared with non-smokers. One theory for this is that poisons (toxins) in cigarette smoke may affect parts of the immune system involved with psoriasis.

What causes psoriasis?

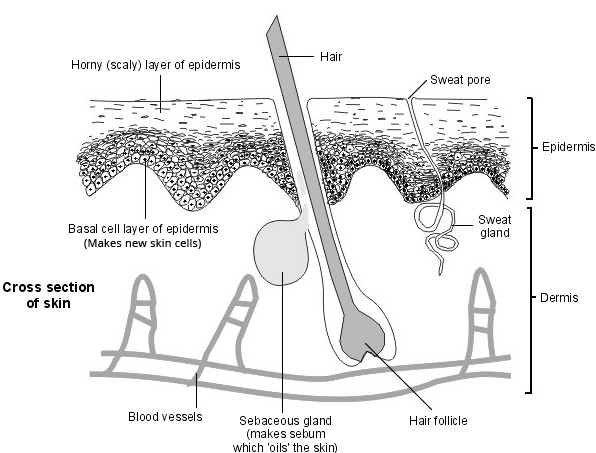

Back to contentsSkin - cross section

Normal skin is made up of layers of skin cells. The top layer of cells (horny layer of the epidermis) is flattened and gradually sheds (they fall off). New cells are constantly being made underneath (in the basal layer of the epidermis) to replace the shed top layer. Cells gradually move from the basal layer to the top horny layer. It normally takes about 28 days for a cell in the basal layer to reach the top layer of skin and to be shed. In psoriasis, this is accelerated, taking three to five days. The diagram above shows a cross-section of normal skin.

Autoimmune disease

People with skin conditions such as psoriasis make more skin cells than normal and make them more quickly. The skin also becomes inflamed. The cause of these changes isn't fully understood but it is now thought that psoriasis is probably an autoimmune disease.

Normally the immune system destroys anything that is foreign - eg, bacteria or viruses. In autoimmune diseases the immune system mistakenly treats parts of the body as foreign. Inherited (genetic) factors also seem to play a part.

It may be that some factor in the environment (perhaps a virus) triggers the condition to start in someone who is already genetically prone to develop it. Research continues to try to find the exact cause.

It is also not known exactly why psoriasis flares up at times but there are several things that are known to aggravate it (see below).

Continue reading below

How is psoriasis diagnosed?

Back to contentsPsoriasis is usually diagnosed by the typical appearance of the rash. No tests are usually needed. Occasionally, a small sample (biopsy) of skin is taken to be looked at under the microscope if there is doubt about the diagnosis.

What triggers psoriasis?

Back to contentsIn most people who have psoriasis, there is no apparent reason why a flare-up happens at any given time. However, in some people, psoriasis is more likely to flare up in certain situations. These include the following:

Stress

Stress seems to trigger a flare-up of psoriasis in some people. There is also some evidence to suggest that the treatment of stress may sometimes be of benefit. Find advice on how to reduce stress in the separate leaflet called Stress Management.

Smoking

Smoking may trigger psoriasis initially to develop in some people and may also aggravate existing psoriasis. Stopping smoking will not only help your psoriasis but will also help to reduce the risk of heart disease and stroke (see below). For tips on stopping, see the separate leaflet called Quit Smoking (Smoking Cessation).

Obesity and overweight

Being obese or overweight makes developing psoriasis more likely and more severe. Losing weight may improve psoriasis in people who are overweight. Find weight loss advice in the separate leaflet called Weight Loss (Weight Reduction).

Alcohol

Drinking a lot of alcohol may cause a flare-up in some people. See the separate leaflet called Alcohol and Sensible Drinking.

Infections

Certain types of infections may cause a flare-up of psoriasis. In particular, a sore throat caused by a certain type of germ (bacterium) called Streptococcus spp. can cause a flare-up of guttate psoriasis or chronic plaque psoriasis.

Medication

Some medicines may possibly trigger or worsen psoriasis in some cases. Medicines that have been suspected of doing this include: beta-blockers (propranolol, atenolol, etc), antimalarial medication, lithium, anti-inflammatory painkillers (ibuprofen, naproxen, diclofenac, etc), angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor medicines, and some antibiotics. In some cases the psoriasis may not flare up until the medication has been taken for weeks or months.

Trauma

Injury to the skin, including excessive scratching, may trigger a patch of psoriasis to develop. The development of psoriatic plaques where the skin has been damaged is known as Köbner's reaction.

Sunlight

Most people with psoriasis say that sunlight seems to help ease their psoriasis. Many people find that their psoriasis is less troublesome in the summer months. However, a few people find that strong sunshine seems to make their psoriasis worse. Severe sunburn (which is a skin injury) can also lead to a flare-up of psoriasis.

Hormonal changes

Psoriasis in women tends to be worst during puberty and during the menopause. These are times when there are some major changes in female hormone levels. Some pregnant women with psoriasis find that their psoriasis symptoms improve when they are pregnant, but it may flare up in the months just after having a baby.

There is no evidence that any particular foods or diets (apart from weight loss diets - see above) are any better or worse for psoriasis than any other.

Psoriasis treatments

Back to contentsThere is no once-and-for-all cure for treating psoriasis. Treatment os psoriasis aims to clear the rash as much as possible. However, as psoriasis tends to flare up from time to time, you may need courses of treatment on and off throughout your life.

There are various treatments options. There is no 'best buy' that suits everybody. The treatment advised by your doctor may depend on the severity, site and type of psoriasis. Also, one treatment may work well in one person but not in another. It is not unusual to try a different treatment if the first one does not work so well.

Many of the treatments of psoriasis include creams or ointments. As a rule, you have to apply creams or ointments correctly for best results. It usually takes several weeks of treatment to clear plaques of psoriasis.

The following is a brief overview of the more commonly used treatments for chronic plaque psoriasis. Unless psoriasis is very severe, treatment is usually with creams or ointments. If these treatments are not successful, you will usually be referred to a skin specialist for advice about other treatments such as medicines and light treatments.

Note: treatments of the less common forms of psoriasis are similar but are not dealt with here. Your doctor will advise.

Will psoriasis go away without any treatment?

Many people have a few red patches (plaques) of psoriasis that are not too bad or not in a noticeable place. Treatment is not essential and some people do not want any treatment if they are only mildly affected.

Having a healthy diet and regular exercise have been shown to improve psoriasis, (as well as reducing the risk of developing heart disease and stroke).

Moisturisers (emollients)

These are essential for anyone with psoriasis, no matter what other treatments they use. They help to soften hard skin and plaques, remove scales and prevent itch. There are many different brands of moisturising creams and ointments so find one that you like.

Using a moisturiser may also make other treatments more effective. However, apply the emollient first and allow about 30 minutes for it to be absorbed into your skin before applying any other treatment. For more information on using moisturisers see the separate leaflet called Moisturisers for Eczema (Emollients).

Vitamin D-based treatments

Calcipotriol, calcitriol and tacalcitol are also called vitamin D analogues, They are commonly used as a psoriasis treatment and often work well. They seem to work by slowing the rate at which skin cells increase.

They come as creams, ointments, lotions and a scalp application. They are easy to use and are less messy and have less of a smell than coal tar or dithranol creams and ointments (below). However, they can cause skin irritation in some people.

They all have a maximum amount that you can use per week. You can read more about this in the leaflet that comes with your preparation and in the separate medicine leaflets called Calcipotriol for psoriasis, Calcitriol ointment for psoriasis and Tacalcitol for psoriasis.

A vitamin D-based treatment is often used in combination with a steroid (eg, calcipotriol/betamethasone), particularly when a flare-up first starts.

They may all cause skin irritation which can lead to redness, soreness or itch in around 1 in 5 users. Any skin irritation that does develop usually settles but sometimes a break in treatment is needed or occasionally stopped completely.

An advantage of calcitriol and tacalcitol is that they are less irritating than calcipotriol. Therefore, one or other may be suitable for use on the face, flexures or genital area if advised by your doctor. Calcipotriol should not be used in these areas.

If you are trying for a baby, are pregnant or are breastfeeding, discuss vitamin D-based treatments with your doctor, as they are only prescribed in this situation if the benefits outweigh the risks.

Steroid creams or ointments

Topical steroids are other commonly used psoriasis treatments. They work by reducing inflammation. They are easy to use and may be a good treatment for difficult areas such as the scalp and face.

However, one problem with steroids is that in some cases, once you stop using the cream or ointment, the psoriasis may come back worse than it was in the first place. Only milder steroid creams or ointments should be used on your face or for psoriasis affecting flexures. See the separate leaflet called Topical Steroids (excluding Inhaled Steroids) for more information on how to use them.

Coal tar preparations

These have been used to treat psoriasis for many years. It is not clear how they work. They may reduce the turnover of the skin cells. They also seem to reduce inflammation and have anti-scaling properties.

Traditional tar preparations are messy to use but modern formulas are more pleasant. Creams, ointments, lotions, pastes, scalp treatments, bath additives and shampoos that contain coal tar are all available.

As a rule, do not use coal tar creams or other coal tar treatments on flexures such as the front of elbows, behind knees, groins, armpits, etc. Also, avoid using them on your face, as you need to be careful not to get them into your eyes.

However, some of the milder creams can be used on your face and flexures - your doctor will advise. Your doctor will also advise you on whether it is safe for you to use coal tar treatments on your genital areas.

Coal tar preparations can have an unpleasant smell and can stain clothes. They may cause skin irritation in some people and skin can become sensitive to sunlight whilst using them. Coal tar preparations should not be used during the first three months of pregnancy. However, they can be used later in the pregnancy and during breastfeeding.

Dithranol

Dithranol has been used for many years for psoriasis and is the most effective treatment that is applied directly to the skin. In most cases a daily application of dithranol to a plaque will get rid of the plaque but you need to persevere as it can take several weeks.

However, it irritates healthy skin, is messy and stains your skin, hair, bedding and clothes, so it is not suitable for everyone with psoriasis, and is now quite hard to get as several manufacturers have stopped producing it. Read more about how to use it in the separate medicine leaflet called Dithranol for psoriasis.

Salicylic acid

Salicylic acid is often combined with other treatments such as coal tar or steroid creams. It is good for loosening and lifting the scales of psoriasis on the body or the scalp. Other treatments tend to work better if the scale is lifted off first by salicylic acid. Salicylic acid can be used as a long-term treatment. You will find more information in the separate leaflet called Salicylic Acid.

Tazarotene

Tazarotene is a gel that is sometimes used to treat psoriasis. It is a vitamin A-based preparation. Irritation of the normal surrounding skin is a common side-effect. This can be minimised by applying tazarotene sparingly to the plaques and avoiding normal skin.

Tazarotene treatment must not be used if you are pregnant or breastfeeding, because it can harm your baby. You can read more about how to use tazarotene in the separate leaflet called Tazarotene for psoriasis.

For scalp psoriasis

A coal tar-based shampoo is often tried first and often works well. Some preparations combine a tar shampoo with either a salicylic acid preparation, a coconut oil/salicylic acid combination ointment, a steroid preparation, a calcipotriol scalp application, or more than one of these.

If you have scalp psoriasis, you may also find it helpful to wear lighter-coloured clothes so that scales falling from your scalp may be seen less easily. Changing your hairstyle to cover up the psoriasis as much as possible may also help. Be careful to brush your hair gently. Scalp treatments can also stain your pillow/pillowcase. So you may wish to cover your pillow with an old pillowcase.

Combinations

Some preparations use a combination of ingredients to treat psoriasis. For example, calcipotriol combined with a steroid may be used when calcipotriol alone has not worked very well. As mentioned, it is not usually wise to use a steroid long-term.

Therefore, one treatment strategy that is sometimes used is calcipotriol combined with a steroid for four weeks, alternating with calcipotriol alone for four weeks. Other combinations such as a coal tar preparation and a steroid are also sometimes used.

Other rotating treatment strategies are also sometimes used. For example, once a flare-up has settled just using treatment at the weekend.

Scalp treatments often contain a combination of ingredients such as a steroid, coal tar, and salicylic acid.

Other treatments for psoriasis

Back to contentsIf you have severe psoriasis then you may need hospital-based treatment. Light therapy (phototherapy) is one type of treatment that can be used. This may involve treatment with ultraviolet B (UVB) light.

Another type of phototherapy is called PUVA - psoralen and ultraviolet light in the A band. This involves taking tablets (psoralen) which enhance the effects of UV light on the skin. You then attend hospital for regular sessions under a special light which emits ultraviolet A (UVA).

Sometimes people with severe psoriasis are given intense courses of treatment, using the creams or ointments described above, but in higher strengths and with special dressings.

If psoriasis is severe and is not helped by the treatments listed above then a powerful medicine which can suppress inflammation is sometimes used. For example, methotrexate, ciclosporin, acitretin, etanercept, infliximab, efalizumab, secukinumab, ustekinumab, bimekizumab, and adalimumab. There is some risk of serious side-effects with these medicines, so they are only used on the advice of a specialist.

Problems related to psoriasis

Back to contentsPeople with psoriasis are more likely to have or develop some other problems in the long term. However, just because you have psoriasis does not mean that you will definitely develop these. The problems include the following:

Joint problems

At least 1 or 2 out of every 10 people with psoriasis also develop inflammation and pains in some joints (arthritis). This is called psoriatic arthritis. Any joint can be affected, but it most commonly affects the joints of the fingers and toes. The cause of this is not clear. It can happen even in people who only have nail psoriasis. See the separate leaflet called Psoriatic Arthritis for more details. You should see a doctor if you have any form of psoriasis and you develop pain or swelling of any joint or pain in your heel (Achilles tendinopathy).

Risk factors for cardiovascular disease

People with psoriasis are more likely to have some of the risk factors for developing cardiovascular disease (heart disease and stroke) such as high levels of cholesterol and other fats in the blood (hyperlipidaemia), high blood pressure (hypertension) and diabetes.

You are more likely to have these risk factors if you have severe psoriasis rather than mild psoriasis. If you have psoriasis you may wish to see your GP or practice nurse to discuss risk factors for cardiovascular disease, and ways of tackling them. See the separate leaflet called Cardiovascular Disease (Atheroma) for more details.

Obesity

Psoriasis is more common in people with obesity.

Psychological problems

Some people with psoriasis may feel embarrassed about their skin problem and develop a negative body image. They may avoid certain activities such as swimming because of fear of uncovering their skin and of other people seeing it. Personal relationships may be affected. Some people with psoriasis develop anxiety and depression.

Can you prevent psoriasis?

Back to contentsUnfortunately, we don't know any way to prevent psoriasis completely. Psoriasis isn't a consequence of something you've done. Psoriasis also isn't a contagious disease - it can't be passed from person to person.

Avoiding triggers and using treatments correctly can help to prevent flare-ups of psoriasis, as discussed above.

What is the outlook for psoriasis?

Back to contentsPsoriasis affects different people in different ways. In general, plaque psoriasis is a persistent (chronic) condition with flare-ups that come and go. However, some studies have shown that, over time, plaque psoriasis may go away completely at some point in around 1 in 3 people. Some people have a number of years where they are free from psoriasis and then it may flare up again.

The less common guttate psoriasis usually goes away completely after a few months. But, if you have an episode of guttate psoriasis, you have a higher than usual chance of developing chronic plaque psoriasis at a later time.

Patient picks for Other skin problems

Skin, nail and hair health

Frostbite

Frostbite is an injury that is caused by exposure of parts of the body to the cold. There are different degrees of frostbite. In superficial frostbite, the skin can recover fully with prompt treatment. However, if frostbite is deep, tissue damage can be permanent and tissue loss can occur. The most important way of preventing frostbite is to get out of the cold. If you are exposed to the cold, make sure that you have adequate protective clothing.

by Dr Toni Hazell, MRCGP

Skin, nail and hair health

Seborrhoeic warts

Seborrhoeic warts are non-cancerous (benign) warty growths that occur on the skin. They usually do not need any treatment.

by Dr Colin Tidy, MRCGP

Further reading and references

- Psoriasis: The assessment and management of psoriasis; NICE Clinical Guideline (October 2012 - last updated September 2017)

- Mansouri Y, Goldenberg G; Biologic safety in psoriasis: review of long-term safety data. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2015 Feb;8(2):30-42.

- Psoriasis - Primary Care Treatment Pathway; Primary Care Dermatology Society, Sept 2017

- Jensen P, Skov L; Psoriasis and Obesity. Dermatology. 2016;232(6):633-639. doi: 10.1159/000455840. Epub 2017 Feb 23.

- Schlager JG, Rosumeck S, Werner RN, et al; Topical treatments for scalp psoriasis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016 Feb 26;2:CD009687. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009687.pub2.

- Ford AR, Siegel M, Bagel J, et al; Dietary Recommendations for Adults With Psoriasis or Psoriatic Arthritis From the Medical Board of the National Psoriasis Foundation: A Systematic Review. JAMA Dermatol. 2018 Aug 1;154(8):934-950. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.1412.

- Psoriasis; NICE CKS, September 2022 (UK access only)

- Sbidian E, Chaimani A, Garcia-Doval I, et al; Systemic pharmacological treatments for chronic plaque psoriasis: a network meta-analysis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2022 May 23;5(5):CD011535. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011535.pub5.

Continue reading below

Article history

The information on this page is written and peer reviewed by qualified clinicians.

Next review due: 24 Apr 2028

26 Apr 2023 | Latest version

Ask, share, connect.

Browse discussions, ask questions, and share experiences across hundreds of health topics.

Feeling unwell?

Assess your symptoms online for free

Sign up to the Patient newsletter

Your weekly dose of clear, trustworthy health advice - written to help you feel informed, confident and in control.

By subscribing you accept our Privacy Policy. You can unsubscribe at any time. We never sell your data.