Chest X-ray - systematic approach

Peer reviewed by Dr Toni Hazell, MRCGPLast updated by Dr Mohammad Sharif Razai, MRCGPLast updated 19 Aug 2024

Meets Patient’s editorial guidelines

- DownloadDownload

- Share

- Language

- Discussion

- Audio Version

Medical Professionals

Professional Reference articles are designed for health professionals to use. They are written by UK doctors and based on research evidence, UK and European Guidelines. You may find one of our health articles more useful.

In this article:

Continue reading below

How to read a chest x-ray

Reading a chest X-ray (CXR) requires a systematic approach. Being systematic helps ensure that obvious pathology is not missed, subtle lesions are detected, conclusions are drawn accurately from films, and management is based on correct interpretations.

There are several ways to examine a CXR; every doctor should develop their own technique. This article is not a tablet of stone but should be a good starting point to develop your own routine.

GPs do not usually see X-ray films, but imaging, including chest X-rays, remains an important and cost-effective diagnostic tool for them.1 There may be occasions when a GP working in a hospital, such as out-of-hours service, has to make decisions based on an unreported film. Therefore, the skill of interpreting X-rays, learned as a junior hospital doctor, should be maintained.

Posteroanterior chest X-ray

Mikael Häggström, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

The 'right film for the right patient'

Back to contentsThis may sound pedantic but it is very important.2 Check that the film bears the patient's name. However, as names can be shared, check other features such as date of birth or hospital number too. The label may also tell of unusual but important features such as anteroposterior (AP) projection or supine position.

After verifying the correct patient, check the date of the film to ensure you are viewing the correct one.

Continue reading below

Technical details

Back to contentsTechnical aspects should be considered briefly:

Check the position of the side marker (typically 'R' for the right side and 'L' for the left side) against features such as the apex of the heart and air bubble in the stomach. A misplaced marker is more common than dextrocardia or situs inversus.

Most X-rays are taken in a posteroanterior (PA) projection. Anteroposterior (AP) projections are usually for bedridden patients and may be noted on the radiograph. If in doubt, check the scapulae's position: in PA views, they are clear of the lungs, whereas in AP views, they overlap. Vertebral endplates are clearer in AP, and laminae in PA. The heart appears larger in AP views due to the reduced distance from the tube to the patient in portable films, which enlarges the heart's shadow.

The normal posture for films is erect. Supine is usually for patients confined to bed. It should be clear from the label. In an erect film, the gastric air bubble is clearly in the fundus with a clear fluid level but, if supine, in the antrum. In a supine film, blood will flow more to the apices of the lungs than when erect. Appreciating this will help prevent a misdiagnosis of pulmonary oedema.

Rotation should be minimal. It can be assessed by comparing the medial ends of the clavicles to the margins of the vertebral body at the same level. Oblique chest films are requested to look for achalasia of the cardia or fractured ribs.

CXR should be taken with the patient in full inspiration but some people have difficulty holding full inspiration. The exception is when seeking a small pneumothorax as this will show best on full expiration. A CXR in full inspiration should have the diaphragm at the level of the 6th rib anteriorly and the liver pushes it up a little higher in the right than on the left. Do not be unduly concerned about the exact degree of inflation.

Penetration is affected by both exposure duration and beam power. Higher kilovoltage (kV) produces a more penetrating beam, affecting image contrast and quality. A poorly penetrated film appears diffusely light, obscuring soft tissues, especially behind the heart, while an over-penetrated film appears dark, making lung markings difficult to see.

Note breast shadows in adult women.

So far you have checked that it is the right film for the right patient and that it is technically adequate.

Systematic search for pathology3

Back to contentsHave a brief look for obvious unusual opacities such a chest drain, a pacemaker or a foreign body. This is a two-dimensional picture and so a central opacity may not be something that was swallowed and is now impacted in the oesophagus. It might be a metal clip from a bra strap or a hair band on a plait.

Look at the mediastinal contours, first to the left and then to the right. The trachea should be central. The aortic arch is the first structure on the left, followed by the left pulmonary artery. The branches of the pulmonary artery fan out through the lung.

Check the cardio-thoracic ratio (CTR). The width of the heart should be no more than half the width of the chest. About a third of the heart should be to the right and two thirds to the left of centre. NB: the heart looks larger on an AP film and thus you cannot comment on the presence or absence of cardiomegaly on an AP film.

The left border of the heart consists of the left atrium above the left ventricle. The right border is only the right atrium alone and above it is the border of the superior vena cava. The right ventricle is anterior and so does not have a border on the PA CXR film. It may be visible on a lateral view.

The pulmonary arteries and main bronchi arise at the left and right hila. Enlarged lymph nodes or primary tumours make the hilum seem bulky. Know what is normal. Abnormality may be caused by lung cancer or enlarged nodes from causes including sarcoidosis (bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy) and lymphoma.

Now look at the lungs. The pulmonary arteries and veins are lighter and air is black, as it is radiolucent. Check both lungs, starting at the apices and working down, comparing left with right at the same level. The lungs extend behind the heart, so try to look there too. Note the periphery of the lungs - there should be few lung markings here. Disease of the air spaces or interstitium increases opacity. Look for a pneumothorax which shows as a sharp line of the edge of the lung.

Ascertain that the surfaces of the hemidiaphragms curve downwards and that the costophrenic and cardiophrenic angles are not blunted. Blunting suggests an effusion. Extensive effusion or collapse causes an upward curve. Check for free air under the hemidiaphragm - this occurs with perforation of the bowel but also after laparotomy or laparoscopy.

Finally look at the soft tissues and bones. Are both breast shadows present? Is there a fractured rib? If so, check again for a pneumothorax. Are the bones destroyed or sclerotic?

There are some areas where it is very easy to miss pathology and so it is worth reviewing the X-ray film again. Pay attention to the apices, periphery of the lungs, under and behind the hemidiaphragms, and behind the heart. The diaphragm slopes backwards and so some lung tissue is below the level of the highest part of the diaphragm on the film.

Continue reading below

Lateral films4

Back to contentsA lateral view may have been requested or performed on the initiative of the radiographer or radiologist. As an X-ray is a two-dimensional shadow, a lateral film helps to identify a lesion in three dimensions. The usual indication is to confirm a lesion seen on a PA film.

The heart lies in the antero-inferior field. Look at the area anterior and superior to the heart; this should be black because it contains aerated lung. Similarly, the area posterior to the heart should be black right down to the hemidiaphragms.

The degree of blackness in these two areas should be similar, so compare one with the other. If the area anterior and superior to the heart is opacified, it suggests disease in the anterior mediastinum or upper lobes. If the area posterior to the heart is opacified there is probably collapse or consolidation in the lower lobes.

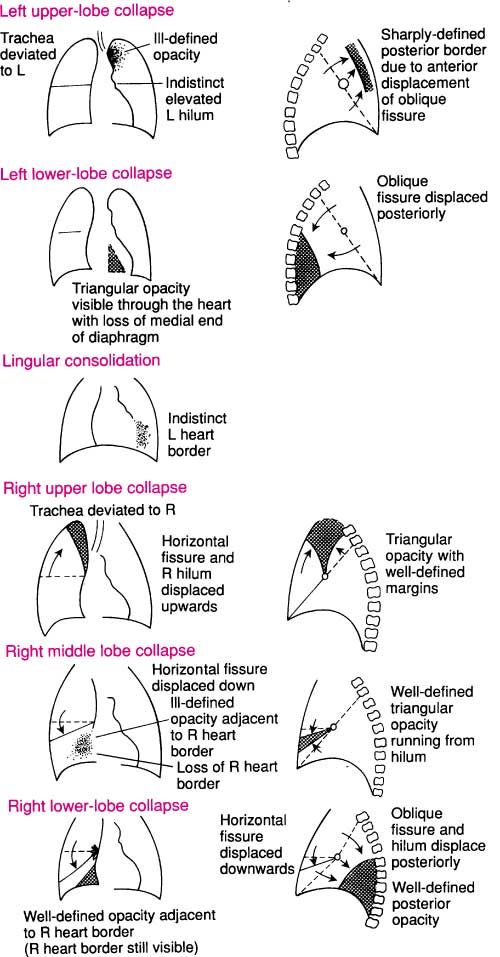

Diagrams

Back to contentsThe following diagrams help to understand the interpretation of the CXR.

Chest X-ray - interpretation

Abnormal opacities

Back to contentsWhen observing an abnormal opacity, note:

Size and shape.

Number and location.

Clarity of structures and their margins.

Homogeneity.

If available, compare with an earlier film.

The common patterns of opacity are:

Collapse and consolidation

Collapse - also called atelectasis - and consolidation are caused by the presence of fluid instead of air in areas of the lung. In an air bronchogram the airway is highlighted against denser consolidation and vascular patterns become obscured.

Confluent opacification of the hemithorax may be caused by consolidation, pleural effusion, complete lobar collapse and after a pneumonectomy. Consolidation is usually interpreted as meaning infection but it is impossible to differentiate between infection and infarction on X-ray. The diagnosis of pulmonary embolism requires a high index of suspicion.

To find consolidation, look for absence or blurring of the border of the heart or hemidiaphragm. The lung volume of the affected segment is usually unaffected.

Collapse of a lobe (atelectasis) may be difficult to see. Look for a shift of the fissures, crowding of vessels and airways and possible shadowing caused by a proximal obstruction like a foreign body or carcinoma.

A small pleural effusion will cause blunting of the costophrenic or cardiophrenic angles. A larger one will produce an angle that is concave upwards. A very large one will displace the heart and mediastinum away from it, whilst collapse draws those structures towards it. Collapse may also raise the hemidiaphragm.

Heart and mediastinum

The heart and mediastinum are deviated away from a pleural effusion or a pneumothorax, especially if it is a tension pneumothorax and towards collapse.

If the heart is enlarged, look for signs of heart failure with an unusually marked vascular pattern in the upper lobes, wide pulmonary veins and possible Kerley B lines. These are tiny horizontal lines from the pleural edge and are typical of fluid overload with fluid collecting in the interstitial space.

If the hilum is enlarged, look for structures at the hilum such as pulmonary artery, main bronchus and enlarged lymph nodes.

Chest X-ray in children5

Back to contentsIt is crucial to consider that the X-ray is from a child when interpreting it. It is still essential to check it is the right film for the right patient.

A child, especially if small, is more likely to be unable to comply with instructions such as keeping still, not rotating and holding deep inspiration.

Technical considerations such as rotation and under- or over-penetration of the film still require attention and they are more likely to be unsatisfactory.

A child is more likely to be laid down and have an AP film with the radiographer trying to catch the picture at full inspiration. This is even more difficult with tachypnoea.6

Assess lung volume

Count down the anterior rib ends to the one that meets the middle of the hemidiaphragm. A good inspiratory film should have the anterior end of the 5th or 6th rib meeting the middle of the diaphragm. More than six anterior ribs shows hyperinflation. Fewer than five indicates an expiratory film or under-inflation.

Tachypnoea in infants leads to air trapping. This is because during expiration, the airways compress, increasing resistance. In infants especially under 18 months, air enters more easily than it leaves, resulting in air trapping and hyperinflation. Conditions such as bronchiolitis, heart failure, and fluid overload can cause this.

With under-inflation, the 3rd or 4th anterior rib crosses the diaphragm. This makes normal lungs appear opaque and a normal heart appears enlarged.

Positioning

Sick children, especially if small, may not be cooperative with being positioned. Check if the anterior ends of the ribs are equal distances from the spine. Rotation to the right makes the heart appear central, while rotation to the left makes the heart look larger and can cause the right heart border to disappear.

Lung density

Divide the lungs into upper, middle and lower zones and compare the two sides. Infection can cause consolidation, as in an adult. Collapse implies loss of volume and has various causes. The lung is dense because the air has been lost.

In children, the cause is usually in the airway, such as an intraluminal foreign body or a mucous plug. Complete obstruction of the airway results in reabsorption of air in the affected lobe or segment. Collapse can also be due to extrinsic compression such as a mediastinal mass or a pneumothorax.

Differentiating between collapse and consolidation can be difficult or impossible, as both are denser. Collapse may pull across the mediastinum and deviate the trachea. This is important, as pneumonia is treated with antibiotics but collapse may require bronchoscopy to find and remove an obstruction.

Pleural effusion

The features of effusion have already been noted for adults. In children, unilateral effusion usually indicates infection whilst bilateral effusion occurs with hypoalbuminaemia as in nephrotic syndrome.

Bronchial wall thickening is a common finding on children's X-rays. Look for 'tram track' parallel lines around the hila. The usual causes are viral infection or asthma but this is a common finding with cystic fibrosis.

Heart and mediastinum

The anterior mediastinum, in front of the heart, contains the thymus gland. It appears largest at about 2 years of age but it continues to grow into adolescence. It grows less fast than the rest of the body and so becomes relatively smaller. The right lobe of the lung can rest on the horizontal fissure, which is often called the sail sign.

Assessment of the heart includes assessment of size, shape, position and pulmonary circulation. The cardiothoracic ratio is usually about 50% but can be more in the first year of life and a large thymus can make assessment difficult, as will a film in poor inspiration.

As with adults, one third should be to the left of centre and two thirds to the right. Assessment of pulmonary circulation can be important in congenital heart disease but can be very difficult in practice.

Further reading and references

- Candemir S, Antani S; A review on lung boundary detection in chest X-rays. Int J Comput Assist Radiol Surg. 2019 Apr;14(4):563-576. doi: 10.1007/s11548-019-01917-1. Epub 2019 Feb 7.

- Bouck Z, Mecredy G, Ivers NM, et al; Routine use of chest x-ray for low-risk patients undergoing a periodic health examination: a retrospective cohort study. CMAJ Open. 2018 Aug 13;6(3):E322-E329. doi: 10.9778/cmajo.20170138. Print 2018 Jul-Sep.

- Speets AM, van der Graaf Y, Hoes AW, et al; Chest radiography in general practice: indications, diagnostic yield and consequences for patient management. Br J Gen Pract. 2006 Aug;56(529):574-8.

- Brady A, Laoide RO, McCarthy P, et al; Discrepancy and error in radiology: concepts, causes and consequences. Ulster Med J. 2012 Jan;81(1):3-9.

- Raoof S, Feigin D, Sung A, et al; Interpretation of plain chest roentgenogram. Chest. 2012 Feb;141(2):545-58. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-1302.

- Feigin DS; Lateral chest radiograph a systematic approach. Acad Radiol. 2010 Dec;17(12):1560-6. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2010.07.004.

- Shi J et al; Chest radiograph (paediatric), Radiopaedia, 2018.

- Bramson RT, Griscom NT, Cleveland RH; Interpretation of chest radiographs in infants with cough and fever. Radiology. 2005 Jul;236(1):22-9. Epub 2005 Jun 27.

Continue reading below

Article history

The information on this page is written and peer reviewed by qualified clinicians.

Next review due: 18 Aug 2027

19 Aug 2024 | Latest version

Ask, share, connect.

Browse discussions, ask questions, and share experiences across hundreds of health topics.

Feeling unwell?

Assess your symptoms online for free