Gestational trophoblastic disease

Peer reviewed by Dr Hayley Willacy, FRCGP Last updated by Dr Colin Tidy, MRCGPLast updated 16 Mar 2023

Meets Patient’s editorial guidelines

- DownloadDownload

- Share

- Language

- Discussion

Medical Professionals

Professional Reference articles are designed for health professionals to use. They are written by UK doctors and based on research evidence, UK and European Guidelines. You may find the Molar pregnancy article more useful, or one of our other health articles.

In this article:

Continue reading below

What is gestational trophoblastic disease?1

Gestational trophoblastic disease (GTD) comprises a group of disorders spanning the premalignant conditions of complete and partial molar pregnancies (also known as hydatidiform moles) through to the malignant conditions of invasive mole, choriocarcinoma and the very rare placental site trophoblastic tumour (PSTT) and epithelioid trophoblastic tumour (ETT). The malignant potential of atypical placental site nodules (PSNs) remains unclear.

If there is any evidence of persistence of GTD after primary treatment, most commonly defined as a persistent elevation of human chorionic gonadotrophin (hCG), the condition is referred to as gestational trophoblastic neoplasia (GTN). The diagnosis of GTN does not require histological confirmation. The diagnosis of complete mole, partial mole, atypical PSN and PSTT/ETT does require histological confirmation.

Molar pregnancies can be subdivided into complete and partial molar pregnancies based on genetic and histopathological features.

Complete molar pregnancies are diploid and androgenic in origin, with no evidence of fetal tissue. Complete molar pregnancies usually (75-80%) arise as a consequence of duplication of a single sperm following fertilisation of an 'empty' ovum. Some complete moles (20-25%) can arise after dispermic fertilisation of an 'empty’ ovum.

Partial molar pregnancies are usually (90%) triploid in origin, with two sets of paternal haploid chromosomes and one set of maternal haploid chromosomes. Partial molar pregnancies occur, in almost all cases, following dispermic fertilisation of an ovum. In a partial mole, there is usually evidence of a fetus or fetal red blood cells. Not all triploid or tetraploid pregnancies are partial moles. For the diagnosis of a partial mole, there must be histopathological evidence of trophoblast hyperplasia.

Cure rates are generally excellent. This is due to central registration and monitoring in the UK, the use of beta human chorionic gonadotrophin (beta-hCG) as a biomarker, and the development of effective treatments.2

Classification

Back to contentsGTD is classified as follows:

Premalignant - hydatidiform mole

Complete hydatidiform mole (CHM).

Partial hydatidiform mole (PHM).

Malignant - GTN

Invasive mole.

Choriocarcinoma.

Placental site trophoblastic tumour (PSTT).

Epithelioid trophoblastic tumour (ETT).

Continue reading below

Aetiology

Back to contentsNormally at conception, half the chromosomes come from the mother and half from the father.

In complete molar pregnancies, all the genetic material comes from the father. An empty oocyte lacking maternal genes is fertilised. Most commonly (75-80%) this arises from a single sperm duplicating within an empty ovum. Less often an empty ovum is fertilised by two sperm. There is no fetal tissue.

In partial molar pregnancies, the trophoblast cells have three sets of chromosomes (triploid). Two sperm are believed to fertilise the ovum at the same time, leading to one set of maternal and two sets of paternal chromosomes. Around 10% of partial moles are tetraploid or mosaic in nature. There is usually evidence of fetal tissue or fetal blood cells in a partial molar pregnancy. An embryo may be present at the start.

An invasive mole develops from a complete mole and invades the myometrium.

Choriocarcinoma most often follows a molar pregnancy but can follow a normal pregnancy, ectopic pregnancy or abortion, and should always be considered when a patient has continued vaginal bleeding after the end of a pregnancy. It has the ability to spread locally, as well as metastasise.

Placental site trophoblastic tumours most often follow a normal pregnancy but occasionally arise from molar pregnancies. These may also be metastatic.

Gestational trophoblastic disease epidemiology1 3

Back to contentsGTD (hydatidiform mole, invasive mole, choriocarcinoma, PSTT) is an uncommon occurrence in the UK, with a calculated incidence of 1 in 714 live births:

There is evidence of ethnic variation in the incidence of GTD in the UK, with women from Asia having a higher incidence compared with non-Asian women (1 in 387 versus 1 in 752 live births, respectively).

The incidence of GTD is associated with age at conception, being higher in the extremes of age (women aged less than 15 years, 1 in 500 pregnancies; women aged more than 50 years, 1 in 8 pregnancies).

However, these figures may under-represent the true incidence of the disease because of problems with reporting, particularly in regard to partial moles.

GTN may develop after a molar pregnancy, a non-molar pregnancy or a live birth. The incidence after a live birth is estimated at 1 in 50 000.

Risk factors

Molar pregnancies may occur at any age but are more common in women aged over 45 years or under 16 years.

There is also an increased risk with multiple pregnancy and previous molar pregnancy.

Women with menarche over the age of 12, light menstruation and a history of use of the oral contraceptive pill may have higher risk.

Asian women have a higher incidence of GTD.

Continue reading below

Clinical presentation of gestational trophoblastic disease1

Back to contentsThe most common presentation is irregular vaginal bleeding, a positive pregnancy test and supporting ultrasound evidence. Vaginal bleeding is the most common presenting symptom of molar pregnancy and is associated with approximately 60% of presentations. Any woman who develops persistent vaginal bleeding after a pregnancy event is at risk of having GTN.

Less common presentations of molar pregnancies include hyperemesis, excessive uterine enlargement, hyperthyroidism, early-onset pre-eclampsia and abdominal distension due to theca lutein cysts.

Very rarely, women can present with haemoptysis, acute respiratory failure or neurological symptoms, such as seizures, likely to be due to metastatic disease affecting the lungs or brain.

Investigations1

Back to contentsUrine and blood levels of hCG

Levels of hCG may be of value in diagnosing molar pregnancies but are far more important in disease follow-up.

The estimation of hCG levels may be of value in diagnosing molar pregnancies.

Women who receive care for a miscarriage or who undergo medical abortion should be advised to do a urinary pregnancy test three weeks after miscarriage/the procedure.

A urine hCG test should be performed in all cases of persistent or irregular vaginal bleeding lasting more than eight weeks after a pregnancy event.

Ultrasound

The use of ultrasound in early pregnancy has led to the earlier diagnosis of molar pregnancy.

Ultrasound features suggestive of a complete molar pregnancy include a polypoid mass between five and seven weeks of gestation and thickened cystic appearance of the villous tissue after eight weeks of gestation with no identifiable gestational sac.

Partial molar pregnancies are associated with an enlarged placenta or cystic changes within the decidual reaction in association with either an empty sac or a delayed miscarriage.

Histology

The definitive diagnosis of a molar pregnancy is made by histological examination.

Pathological features consistent with the diagnosis of complete molar pregnancies include: absence of fetal tissue; extensive hydropic change to the villi; and excess trophoblast proliferation.

Features of a partial molar pregnancy include: presence of fetal tissue; focal hydropic change to the villi; and some excess trophoblast proliferation. Ploidy status and immunohistochemistry staining for p57, a paternally imprinted gene, may help in distinguishing partial from complete molar pregnancies.

The histological assessment of material obtained from the medical or surgical management of all miscarriages is recommended to exclude trophoblastic neoplasia if no fetal parts are identified at any stage of the pregnancy.

There is no need to send pregnancy tissue for histological examination routinely following therapeutic abortion, provided that fetal parts have been identified at the time of surgical abortion or on prior ultrasound examination.

Staging investigations where metastatic disease is suspected

Doppler pelvic ultrasound for local pelvic spread and vascularity.

CXR or lung CT scan to diagnose lung metastases.

CT scanning for liver or other intra-abdominal metastases.

MRI scanning for brain metastases.

Staging1

Back to contentsThe staging system of the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) is as follows:

Stage I: disease confined to the uterus.

Stage II: extends outside the uterus but is limited to the genital structures (adnexa, vagina, broad ligament).

Stage III: extends to the lungs with or without genital tract involvement.

Stage IV: all other metastatic sites.

Gestational trophoblastic disease treatment and management1

Back to contentsRegistration

Outcomes for women with GTN and GTD are better with ongoing care from GTD centres. The registration of affected women with a GTD centre represents a minimum standard of care. Women with the following diagnoses should be registered and require follow-up as determined by the screening centre:

Complete molar pregnancy/partial molar pregnancy.

Twin pregnancy with complete or partial molar pregnancy.

Limited macroscopic or microscopic molar change suggesting possible early complete or partial molar pregnancy/choriocarcinoma.

PSTT or ETT.

Atypical placental site nodule (PSN).

The gynaecologist treating affected women will register the woman with one of the three centres: Ninewells Hospital (Dundee), Charing Cross Hospital (London) and Weston Park Hospital (Sheffield).

Management of hydatidiform moles

Suction curettage is the method of choice for removal of complete molar pregnancies.

Suction curettage is the method of choice for removal of partial molar pregnancies except when the size of fetal parts deters the use of suction curettage and then medical removal can be used.

A urinary pregnancy test should be performed three weeks after medical management of failed pregnancy if products of conception are not sent for histological examination.

Anti-D prophylaxis is required following evacuation of a PHM.

Excessive vaginal bleeding can be associated with molar pregnancy and a senior surgeon directly supervising surgical evacuation is advised.

The use of oxytocin infusion prior to completion of the evacuation is not recommended. A single dose of an oxytocic can be used following evacuation if there is excessive bleeding.

If the woman is experiencing significant haemorrhage prior to evacuation, surgical evacuation should be expedited and the need for oxytocin infusion weighed up against the risk of tumour embolisation.

Twin pregnancies with a viable fetus and a molar pregnancy

The pregnancy should be allowed to proceed if the mother wishes, following appropriate counselling.

The probability of achieving a viable baby is poor (around 25%) and there is a high risk of complications such as premature delivery and pre-eclampsia.

There is no increased risk of developing persistent GTD after this type of molar pregnancy and outcome after chemotherapy is unaffected.

UK (Charing Cross Hospital) protocol for surveillance after hydatidiform mole4

Two-weekly serum and urine samples until hCG concentrations are normal.

In a partial mole, normal levels are confirmed four weeks later and if results remain normal, surveillance may end.

For a complete mole, after hCG levels return to normal, monthly urine hCG testing is continued. This continues for six months from evacuation if levels have normalised within eight weeks; if not, monitoring continues for six months from when levels became normal.

All women should notify the screening centre at the end of any future pregnancy, whatever the outcome of the pregnancy. Levels of hCG are measured 6-8 weeks after the end of the pregnancy to exclude disease recurrence.

Indications for chemotherapy in GTD3 4

Plateaued or rising hCG levels after evacuation.

Histological evidence of choriocarcinoma.

Evidence of metastases in the brain, liver, or gastrointestinal (GI) tract, or radiological opacities >2 cm on CXR.

Pulmonary, vulval, or vaginal metastases unless hCG concentrations are falling.

Heavy vaginal bleeding or evidence of GI or intraperitoneal haemorrhage.

Serum hCG greater than 20,000 IU/L more than four weeks after evacuation, because of the risk of uterine perforation with further evacuation attempts.

Raised hCG level six months after evacuation (even if falling).

Chemotherapy regimes

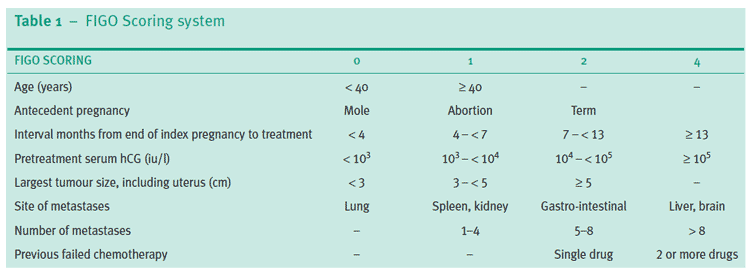

Women with evidence of persistent GTD should undergo assessment of their disease followed by chemotherapy. Treatment used is based on the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) 2000 scoring system for GTN following assessment at the treatment centre.

FIGO scoring system RCOG GT37

© Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists; reproduced with permission.

The total score is obtained by adding the individual scores for each prognostic factor. Low-risk 0-6; high-risk ≥7.

Women with GTN may be treated with single-agent or multi-agent chemotherapy. PSTT and ETT are now recognised as variants of GTN. They may be treated with surgery because they are less sensitive to chemotherapy.

Women with FIGO scores of 6 or less are at low risk and are treated with single-agent intramuscular methotrexate, alternating daily with folinic acid for one week followed by six rest days.

Women with scores of 7 or greater are at high risk and are treated with intravenous multi-agent chemotherapy, which includes combinations of methotrexate, dactinomycin, etoposide, cyclophosphamide and vincristine.

Treatment is continued, in all cases, until the hCG level has returned to normal and then for a further six consecutive weeks. Women suspected of choriocarcinoma require more extensive investigation in the specialist centre, including computerised tomography of the chest and abdomen, or magnetic resonance imaging of the head and pelvis, all with contrast in addition to the serum hCG and a Doppler ultrasound of the pelvis.

Any woman with a score of 13 or greater is now recognised to have a higher risk of early death (within four weeks), often due to bleeding into organs, or late death due to multihyphenate drug-resistant disease.

Rarely, women with multi-relapsed disease will require high-dose chemotherapy with stem cell recovery.

A 2016 Cochrane review found that dactinomycin (actinomycin D) is probably more likely to achieve a primary cure for low-risk disease, with fewer treatment failures than the methotrexate regimen, and that the side effect profile is similar.5 However, dactinomycin (actinomycin D) may be associated with a greater risk of severe adverse events. The review concluded that there were ongoing trials which are likely to contribute significantly to available evidence in this field and that higher-certainty evidence is still needed.

Prophylactic chemotherapy may reduce the risk of progression to GTN in women with complete moles who are at a high risk of malignant transformation. However, current evidence in favour of prophylactic chemotherapy is limited.6

Follow-up1

Back to contentsFor complete molar pregnancy, if hCG has reverted to normal within 56 days of the pregnancy event then follow-up will be for six months from the date of uterine removal.

If hCG has not reverted to normal within 56 days of the pregnancy event then follow-up will be for six months from normalisation of the hCG level.

Follow-up for partial molar pregnancy is concluded once the hCG has returned to normal on two samples, at least four weeks apart.

Women who have not received chemotherapy no longer need to have hCG measured after any subsequent pregnancy event.

Women who have a pregnancy following a previous molar pregnancy, which has not required treatment for GTN, do not need to send a post-pregnancy hCG sample.

Histological examination of placental tissue from any normal pregnancy, after a molar pregnancy, is not indicated.

Future pregnancy1

Back to contentsWomen are advised not to conceive until their follow-up is complete. Elevated hCG during the follow-up period may indicate recurrence. Pregnancy is best avoided during the follow-up period until the success of treatment has been established.

Women who undergo chemotherapy are advised not to conceive for one year after completion of treatment, as a precautionary measure.

Women who have a pregnancy following a previous molar pregnancy, which has not required treatment for GTN, do not need to send a post-pregnancy hCG sample.

Women should be advised not to conceive until their hCG follow-up is complete.

Contraception following treatment7

Back to contentsWomen should be advised that most methods of contraception can be safely used after treatment for GTD and can be started immediately after uterine evacuation, with the

exception of intrauterine contraception (IUC).

IUC should not be inserted in women with persistently elevated hCG levels or malignant disease. IUC should not normally be inserted until hCG levels have normalised but may be considered on specialist advice with insertion in a specialist setting for women with decreasing hCG levels following discussion with a GTD centre.

Emergency contraception (EC) is indicated if unprotected sexual intercourse (UPSI) takes place from five days after treatment for GTD.

Prognosis1

Back to contentsOutcomes for women with GTN and GTD are better with ongoing management from GTD centres. The registration of affected women with a GTD centre represents a minimum standard of care.

In the UK, the registration and treatment programme has a cure rate of 98-100%, and a chemotherapy rate of 0.5-1.0% for GTN after partial molar pregnancy and 13-16% after complete molar pregnancy.

The outlook for women treated for GTN is generally excellent with an overall cure rate close to 100%. The cure rate for women with a FIGO score of 6 or less is almost 100%, while the rate for women with a score of 7 or greater is 94%.

The prognosis for a woman with GTN after a non-molar pregnancy may be worse owing to delay in diagnosis or advanced disease, such as liver or central nervous system disease, at presentation.

Further pregnancies are achieved in approximately 80% of women following treatment for GTN with either methotrexate alone or multi-agent chemotherapy.

The risk of a further molar pregnancy is low (approximately 1%) and is associated more with complete than partial molar pregnancy. Women who become pregnant following a molar pregnancy are not at increased risk of maternal complications.

However, women exposed to a molar pregnancy prior to the index birth are at an almost 25% increased risk of preterm birth, whereas women with at least one birth between the molar pregnancy and the index birth are at an increased risk of a large-for-gestational-age birth and stillbirth.

There is an increased risk of premature menopause for women treated with combination agent chemotherapy.

Women, especially those approaching the age of 40 years, should be warned of the potential negative impact on fertility, particularly when treated with high-dose chemotherapy.

The use of exogenous oestrogens, including HRT, and other fertility drugs may be used once hCG levels have returned to normal.

Further reading and references

- International Society for the Study of Trophoblastic Diseases

- Hydatidiform Mole and Choriocarcinoma UK Information and Support Service

- Bolze PA, Attia J, Massardier J, et al; Formalised consensus of the European Organisation for Treatment of Trophoblastic Diseases on management of gestational trophoblastic diseases. Eur J Cancer. 2015 Sep;51(13):1725-31. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2015.05.026. Epub 2015 Jun 16.

- Gestational Trophoblastic disease (Choriocarcinoma – all ages); NHS England. June 2020.

- Management of Gestational Trophoblastic Disease; Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (September 2020).

- Froeling FE, Seckl MJ; Gestational trophoblastic tumours: an update for 2014. Curr Oncol Rep. 2014 Nov;16(11):408. doi: 10.1007/s11912-014-0408-y.

- Gestational trophoblastic disease: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis treatment and follow-up; European Society of Medical Oncology (Sept 2013)

- Hydatidiform Mole and Choriocarcinoma UK Information and Support Service

- Lawrie TA, Alazzam M, Tidy J, et al; First-line chemotherapy in low-risk gestational trophoblastic neoplasia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016 Jun 9;(6):CD007102. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007102.pub4.

- Wang Q, Fu J, Hu L, et al; Prophylactic chemotherapy for hydatidiform mole to prevent gestational trophoblastic neoplasia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017 Sep 11;9(9):CD007289. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007289.pub3.

- CEU Clinical Guidance: Contraception After Pregnancy; Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare (January 2017, amended October 2020)

Continue reading below

Article history

The information on this page is written and peer reviewed by qualified clinicians.

Next review due: 14 Mar 2028

16 Mar 2023 | Latest version

Ask, share, connect.

Browse discussions, ask questions, and share experiences across hundreds of health topics.

Feeling unwell?

Assess your symptoms online for free