Menstruation and menstruation disorders

Peer reviewed by Dr Colin Tidy, MRCGPLast updated by Dr Hayley Willacy, FRCGP Last updated 1 Apr 2022

Meets Patient’s editorial guidelines

- DownloadDownload

- Share

- Language

- Discussion

- Audio Version

Medical Professionals

Professional Reference articles are designed for health professionals to use. They are written by UK doctors and based on research evidence, UK and European Guidelines. You may find the Periods and period problems article more useful, or one of our other health articles.

In this article:

Continue reading below

What is menstruation?

Normal menstruation is the monthly cycle of blood loss per vagina, resulting from the breakdown of the uterine lining when implantation of a fertilised ovum does not occur. Menstruation is not a sign of ovulation but of the fact that the hormonal controls and the reproductive tract's responses to it work. The female reproductive system consists of the ovaries, Fallopian tubes, uterus, vagina and the vulva.

The onset of menstruation in girls is known as the menarche and the menstrual cycle continues until the menopause. Normal menstrual loss is about 5-80 ml per day for 4-5 days per month.1 The amount of blood loss varies between individuals but tends to get heavier with age. A cycle may last between 21-35 days.

Puberty and menarche

Back to contentsPuberty is a process of maturation of the sexual and secondary sexual characteristics, with menarche as a step within that process.

At birth all the woman's immature follicles lie dormant in the ovaries. No more are produced. This may be an important consideration in some circumstances - eg, in childhood leukaemias and chemotherapy, as they may need to be preserved to safeguard future fertility potential of the child.

The ovarian follicles lie dormant from birth until puberty arrives and the rising hormones lead to the maturation of several ovarian follicles per month; usually only one matures and is released.

Menarche is the start of the first menstrual period. Menarche has occurred at a younger age during the last century. This may be due to improved nutrition (and subsequent weight) in the population.

The average age of menarche is 13 years but it can be as early as 8 years and as late as 16 years and still be normal. Premature or delayed menarche should be investigated - ie before 8 years or after 15 years.2 See the separate Normal and Abnormal Puberty, Delayed Puberty and Precocious Puberty articles for more information.

Normal menstruation then occurs in a monthly cycle until menopause, unless interrupted by pregnancy.

Continue reading below

Hormonal control and menstruation3

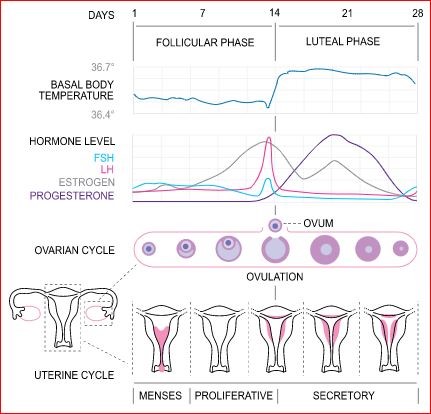

Back to contentsMenstrual Cycle

© Isometrik, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

By Isometrik, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The menstrual cycle is under the control of three sets of hormones:

Gonadotrophin-releasing hormones - luteinising hormone-releasing hormone (LHRH) and follicle-stimulating hormone-releasing hormone (FSHRH).

Gonadotrophins - luteinising hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH).

Ovarian hormones - oestrogen and progesterone.

The gonadotrophin hormone-releasing factors from the hypothalamus control the release of the pituitary hormones; the gonadotrophins - FSH and LH. They are produced by the anterior pituitary and control the ovarian hormones oestrogen and progesterone.

During the follicular phase a rise in FSH from the pituitary gland stimulates the development of several follicles on the surface of the ovary. Each follicle contains an egg. Later, as the FSH level decreases, only one follicle continues to develop. This follicle also produces oestrogen.

The LH peaks mid-cycle, triggering the release of the ovum - ovulation, which usually occurs 16-32 hours after the surge begins. The LH level falls a couple of days later.

The oestrogen level from the ovaries increases gradually towards ovulation and peaks during the LH surge.

The progesterone level starts to rise towards follicle release, preparing the endometrial lining of the uterus for implantation.

Post-ovulation - the luteal phase - levels of LH and FSH decrease. The ruptured follicle closes (after releasing the egg) and forms a corpus luteum, which produces progesterone. If the ovum is fertilised, the progesterone levels are maintained by the corpus luteum and the endometrium is maintained.

If the ovum is not fertilised the corpus luteum starts to degenerate and progesterone and oestrogen levels start to fall. The endometrial blood vessels constrict and the endometrial lining breaks down and is shed.

The first day of the menstrual cycle is counted as the first day of the bleed - Day 1. The menstrual cycle runs from the first day of menstruation to the next first day.

The hormonal swings may be associated with changes in mood and libido and with headaches in some women. However, some studies have not demonstrated good evidence for premenstrual mood symptoms.4 5

The typical changes of the menstrual cycle may help to guide natural family planning, if a woman wishes. Several methods are available, including calendar, temperature and cervical mucus observation, or palpating the cervix.6

Range of menstruation problems

Back to contentsMenstrual disorders may include:

Quantity: usually perceived as too great a loss - menorrhagia. This is defined as excessive menstrual blood loss which interferes with a woman's physical, social, emotional and/or material quality of life.7 Research studies tend to use a loss above 80 ml per menses to define menorrhagia, although women who complain of menorrhagia rarely lose this much blood. Menorrhagia may cause iron-deficiency anaemia.

Timing: may be too frequent (polymenorrhoea - more than one period per calendar month) or infrequent (oligomenorrhoea) or absent (amenorrhoea).8

Duration of bleeding: normal range is 3-7 days.

Time of onset: precocious puberty (before 8 years) or delayed puberty (after 15 years).

Associated symptoms: painful periods (dysmenorrhoea), premenstrual syndrome.

Continue reading below

Causes of abnormal bleeding during menstruation9

Back to contentsNon-reproductive causes

Normal menstruation can be affected by any failure of the clotting system in the body. Systemic disease disorders of blood clotting may therefore be a cause - eg, von Willebrand's disease or prothrombin deficiency, leukaemia, immune thrombocytopenia (ITP) and hypersplenism.

Hypothyroidism - can sometimes be associated with menorrhagia or intermenstrual bleeding (IMB).

Cirrhosis - associated with reduced ability of the liver to metabolise oestrogens, and hypoprothrombinaemia.

Diseases of the reproductive tract

The most common causes during fertile age are those related to pregnancy - eg, threatened, incomplete or missed abortion, ectopic pregnancy. Trophoblastic disease should be considered in women with recent pregnancy.

Malignancies - endometrial and cervical carcinoma are the most common; also ovarian carcinoma.

Endometritis - usually presents as intermenstrual spotting.

Uterine fibroids, endometrial polyps and adenomyosis.

Cervical lesions - erosions, polyps and cervicitis - can present as postcoital spotting.

Genetic conditions such as Turner syndrome with gonadal abnormality.

Dysfunctional uterine bleeding (DUB) is defined as abnormal uterine bleeding in the absence of organic disease.1 It usually presents as heavy menstrual bleeding (menorrhagia). The diagnosis of DUB can only be made once all other causes of abnormal or heavy uterine bleeding have been excluded. The pathophysiology is largely unknown.

Iatrogenic - hormones used for contraception or hormone replacement therapy (HRT) or management of other conditions. The combined oral contraceptive (COC) pill causes an artificial withdrawal bleed - ie early menopause or pregnancy can be masked, and women may complain of breakthrough bleeding. Women on hormonal contraception such as the contraceptive progestogen-only pill (POP) may have problems with erratic menstruation. Treatment such as chemotherapy or pelvic irradiation may cause ovarian failure.

Other factors that may affect the menstrual cycle

Breastfeeding usually delays the return of normal menstruation postpartum, particularly if exclusive and may form the basis for the lactation amenorrhoea method (LAM) of contraception for the first six months of the baby's life.

Rapid weight change - increase or decrease.

Body weight below a certain level - eg, in eating disorders - particularly anorexia nervosa.

Emotional stress - eg, fear of pregnancy/phantom pregnancy.

Significant Illness.

Medication - eg, hormones, cytotoxics, some psychotropic drugs (eg, risperidone).

Investigations and menstruation management

Back to contentsThese will depend on the possible cause. Further detailed information will be found by following the links to each separate dedicated article.

Coping with normal menstruation

Back to contentsHow a woman chooses to deal with the physical blood loss is a matter of personal preference. Wide ranges of sizes and types of absorbent disposable towels and tampons are available.

Period pains respond well to anti-inflammatories - eg, mefenamic acid.

Some women may need a combination of towels and tampons for overnight use, to prevent soiling bed linen.

Sometimes women may wish to postpone their cycle because of holidays, etc. This can be achieved by:

Medroxyprogesterone acetate (Provera®) 10 mg bd or tds, starting three days before the anticipated onset of menstruation. Menstruation will occur about three days after stopping taking the medroxyprogesterone.

Extended use of the COC pill; running packs together and omitting the pill-free week. This is safe and is often used for three packs (tricycling) but sometimes extended use for more than three months. Some women may experience breakthrough bleeding if they use such a continuous COC pill regimen.

Further reading and references

- Davis E, Sparzak PB; Abnormal Uterine Bleeding

- Klein DA, Emerick JE, Sylvester JE, et al; Disorders of Puberty: An Approach to Diagnosis and Management. Am Fam Physician. 2017 Nov 1;96(9):590-599.

- Thiyagarajan DK, Basit H, Jeanmonod R; Physiology, Menstrual Cycle

- Romans S, Clarkson R, Einstein G, et al; Mood and the menstrual cycle: a review of prospective data studies. Gend Med. 2012 Oct;9(5):361-84. doi: 10.1016/j.genm.2012.07.003.

- Gudipally PR, Sharma GK; Premenstrual Syndrome

- Contraception - natural family planning; NICE CKS, June 2021 (UK access only)

- Heavy menstrual bleeding: assessment and management; NICE Guideline (March 2018 - updated May 2021)

- Klein DA, Paradise SL, Reeder RM; Amenorrhea: A Systematic Approach to Diagnosis and Management. Am Fam Physician. 2019 Jul 1;100(1):39-48.

- Munro MG, Critchley HOD, Fraser IS; The two FIGO systems for normal and abnormal uterine bleeding symptoms and classification of causes of abnormal uterine bleeding in the reproductive years: 2018 revisions. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2018 Dec;143(3):393-408. doi: 10.1002/ijgo.12666. Epub 2018 Oct 10.

Continue reading below

Article history

The information on this page is written and peer reviewed by qualified clinicians.

Next review due: 31 Mar 2027

1 Apr 2022 | Latest version

Ask, share, connect.

Browse discussions, ask questions, and share experiences across hundreds of health topics.

Feeling unwell?

Assess your symptoms online for free