Otitis externa and painful, discharging ears

Peer reviewed by Dr Colin Tidy, MRCGPLast updated by Dr Hayley Willacy, FRCGP Last updated 30 May 2022

Meets Patient’s editorial guidelines

- DownloadDownload

- Share

- Language

- Discussion

- Audio Version

Medical Professionals

Professional Reference articles are designed for health professionals to use. They are written by UK doctors and based on research evidence, UK and European Guidelines. You may find the Outer ear infection (otitis externa) article more useful, or one of our other health articles.

In this article:

Continue reading below

What is otitis externa?

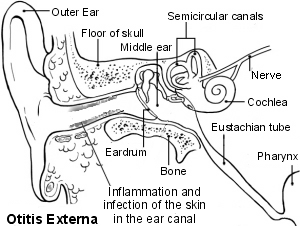

Otitis externa is inflammation of the outer ear. Otitis externa includes all the inflammatory conditions of the auricle, external auditory canal and outer surface of the eardrum. It can be localised or diffuse and may be acute or chronic. Acute diffuse otitis externa is also called swimmer's ear.

Epidemiology

Back to contentsOtitis externa is a common presenting complaint in UK general practice, with studies suggesting that it seen in around 1-3% of population.1 It is believed that around 10% of people will experience at least one episode in their lifetime.2

It is most common in adults and when in children usually affects 7- to 12-year-olds.3

Around 3% of cases seen in UK general practice are referred to secondary care.4

Otitis externa risk factors5 6

Hot and humid climates.

Swimming.

Older age.

Immunocompromise (eg, HIV).

Diabetes mellitus.

Narrow external auditory meatus (hereditary or acquired through chronic infection, exostoses).

Obstruction of normal meatus - eg, keratosis obturans, foreign body, hearing aid, hirsute ear canal.

Insufficient wax: Too little cerumen (often through over-cleaning) can predispose to infection as it reduces the protective function of cerumen allows the canal pH to rise.

Wax build-up: excessive cerumen can lead to obstruction, retention of water and debris, and infection.

Dermatological conditions: eczema, seborrhoeic dermatitis.

Allergic, atopic or irritant dermatitis affecting the ear canal epithelium.

Trauma to ear canal - eg, from cotton buds, radiotherapy.

Microbiologica - eg, from active otitis media, exposure to Pseudomonas aeruginosa or fungi.

Previous tympanostomy.

Radiotherapy to ear.

Continue reading below

Anatomy of the ear canal3

Back to contentsThe outer third of the canal is formed of elastic cartilage: the anterior and lower wall are cartilaginous and the superior and back wall are fibrous. The cartilage is the continuation of the pinna. The bony part forms the inner two thirds. The bony part is much shorter in children and is only a ring (annulus tympanicus) in the newborn.

Size and shape of the canal vary among individuals. The canal is approximately 2.5 cm (1 in) long and 0.7 cm (0.28 in) in diameter, in a sigmoid shape running from behind and above downward and forward. On the cross-section, it is of oval shape.

The canal is self-cleaning, which keeps it clear of debris. It achieves this by epithelial migration; the skin surface moves laterally from the tympanic membrane towards the ear canal opening.

Ear wax (cerumen) is composed of epithelial cells, lysozymes and oily secretions from sebaceous and ceruminous glands in the outer cartilaginous part of the canal. The composition varies from individual to individual, depending on diet, age and environment. Cerumen assists with cleaning and lubrication and provides some protection from bacteria, dust and insects. It creates an acidic coat which also helps to inhibit bacterial and fungal growth. Its hydrophobic properties also prevent water from reaching the canal skin and causing maceration.

The outer part of the canal is also protected by hairs which help to prevent objects from entering the ear canal and which aid in desquamation and skin migration out of the canal.

The ear - otitis externa

Aetiology

Back to contentsOtitis externa results from a disturbance of the lipid/acid balance of the ear canal.

Otitis externa is most usually infectious but may be caused by allergies, irritants or inflammatory conditions (all of which may also underlie bacterial infection).

Infections

Infection of the outer ear is usually bacterial (90%) or fungal (10%).7 Most cases involve multiple organisms, with the majority involving Staphylococcus aureus and/or P. aeruginosa.8

Fungal infection usually follows prolonged treatment with antibiotics, with or without steroids. About 10% of cases are fungal. 90% of fungal infections involve Aspergillus spp. and the rest are Candida spp. Dermatophyte infection may occur and seborrhoeic dermatitis may be followed by infection with Malassezia spp.

Herpes zoster (Ramsay Hunt syndrome).

Infection may be localised to an infected hair follicle, causing a furuncle or localised otitis externa (S. aureus is the usual infecting organism).

Skin inflammation

Causes include:

Irritants

These include:

Topical medications, hearing aids or earplugs:

Aggravating factors, such as ear trauma from foreign bodies in the ear, cotton buds, ear syringing or hearing aids.

Water in the ear in swimmers, especially in polluted water.

Chemicals including hair spray, hair dyes and cerumenolytics.

Continue reading below

Otitis externa symptoms5

Back to contentsThe main symptoms of otitis externa are pain and itching. There may also be discharge and hearing loss. Findings on otoscopy are:

Ear canal with erythema, oedema and exudate.

Mobile tympanic membrane.

Pain with movement of the tragus or auricle.

Pre-auricular lymphadenopathy.

Otitis externa is generally more severe with any of the following:

Oedematous ear canal narrowed and obscured by debris.

Hearing loss.

Discharge.

Regional lymphadenopathy.

Cellulitis spreading beyond the ear.

Fever.

Acute diffuse otitis externa

Moderate temperature (less than 38°C) and lymphadenopathy.

Swelling is diffuse.

Pain is variable with possible pruritus.

Moving the ear or jaw is painful.

There may be slight thick discharge, which can become bloody later.

Hearing may be impaired.

Bacterial infection is common.

Severe otitis externa

© James Heilman, MD (Own work),CC-BY-3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

By James Heilman, MD (Own work), CC-BY-3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Swimmer's ear is an interchangeable term with acute otitis externa and whilst it's prevalence is about five times greater in swimmers than in non-swimmers, you do not have to be a swimmer to have swimmer's ear. However, the term is often used to refer to acute otitis externa brought on by water remaining in the ear after swimming, creating a perfect medium for bacterial growth.

Chronic otitis externa

If due to infection this is usually fungal. Underlying skin conditions, diabetes, immunosuppression or prolonged use of antibiotic ear drops may contribute.

Symptoms are as for acute diffuse otitis externa. Discharge and itch are common.

Superficial fungal infection

Tends to be chronic.

Complaints are of itching and discomfort.

Discharge is variable.

See the separate Fungal Ear Infection (Otomycosis) article.

Furuncle

Small localised infection with severe pain in the ear and local swelling of the canal.

Pyrexia is moderate (less than 38°C).

There may be posterior auricular lymphadenopathy.

Auriscope examination can be very painful.

If the lesion bursts there is sudden relief of pain.

Contact dermatitis

Irritant dermatitis is usually insidious in onset with lichenification.

Allergic otitis externa is usually faster in onset with itching, erythema and oedema.

If otitis externa persists despite conventional treatment, consider allergy, usually to an aminoglycoside. Patch testing may be required.9

Other skin diseases

If seborrhoeic dermatitis or atopic dermatitis underlies the infection there will usually be local evidence of that disease.

Necrotising (malignant) otitis externa10

A life-threatening extension of otitis externa into the mastoid and temporal bones.

Usually due to P. aeruginosa or S. aureus.

Usually affects elderly patients with diabetes or patients who are immunocompromised.

Pain and headache of greater intensity than clinical signs would suggest.

Facial nerve palsy is a red flag sign but is not necessarily associated with a poorer prognosis.11

Criteria for diagnosis include:12

Pain.

Oedema.

Exudate.

Granulation tissue (may be present at the junction of bone and cartilage).

Microabscess (when operated upon).

Positive bone scan or failure of local treatment.

Pseudomonas spp. in culture.

Typical additional features:

Diabetes.

Cranial nerve involvement.

Positive radiograph.

A debilitating underlying condition.

Immunosuppression - eg, HIV/AIDS, chemotherapy.

Older age.

Atypical patients are not uncommon.13

A technetium bone scan is needed to exclude osteomyelitis.

Computed tomography may be useful in predicting the extent of skull involvement.14

Investigations5

Back to contentsSwabs are not generally recommended but may be useful if there has been treatment failure for otitis externa, or the situation looks atypical.8 If treatment fails or otitis externa recurs frequently, consider sending an ear swab for bacterial and fungal microscopy and culture. A swab is best taken from the medial aspect of the ear canal under visualisation to reduce contamination.

Identifying the organism is not usually therapeutically helpful:

Reported bacterial susceptibility may not correlate with clinical outcomes because sensitivities are determined for systemic administration. Much higher concentrations of antibiotic are achieved with topical application. Almost all bacteria recovered are sensitive to these concentrations.

It is not possible to tell from the culture results whether the isolated organisms are causative or are contaminants. In particular, fungi are often present after antibacterial drops have been used (which will have suppressed the normal bacterial flora) but may not be causing the inflammation.

The integrity of the tympanic membrane should be assessed if possible. It may be impossible to visualise but perforation can be assumed if the person:

Can taste medication placed in the ear; or

Can blow air out of the ear when the nose is pinched; or

Has a tympanostomy tube in situ.

Differential diagnosis15

Back to contentsForeign bodies may be present.

Impacted wax can cause pain and deafness. Drops will make it swell and can aggravate it before removal.

Otitis media is painful but, if the drum bursts, the pain ceases and a discharge follows.

A chronic discharging ear is associated with chronic suppurative otitis media and possibly cholesteatoma.

If the ear is swollen with a canal that bleeds readily on contact, consider malignancy.

Pain can be referred from the sphenoidal sinus, teeth, neck, or throat.

Barotrauma usually affects divers and, less commonly, those who have recently flown; however, it can result from a blow to the ear.

Dermatological disease, as listed in 'Presentation', above.

Otitis externa treatment and management3 5

Back to contentsThe aim of treatment is:

To settle symptoms (including pain).

To cure infection.

To reduce risk of recurrence.

To prevent complications.

Treatment and management of otitis externa is the same for adults and for children:

Acute otitis externa

Usually managed with topical drops.

Wicking and removal of debris to clean the canal and facilitate topical treatment can be helpful.

If initial therapy fails then reconsider diagnosis.

If there is cellulitis or cervical lymphadenopathy, oral antibiotics may be e indicated but they are seldom helpful in uncomplicated cases.

Patients with systemic symptoms need same-day ENT review and may need admission for intravenous antibiotics.

Chronic otitis externa

Chronic otitis externa is that which has been present for more than three months. There has often been modification of the normal flora by treatment. Focus is on trying to identify the underlying cause (possibly a skin condition such as eczema) or aggravating factors. Consider:

Inadequate aural toilet.

Continued trauma from scratching or swimming.

Poor compliance with treatment.

Contact sensitivity to previous topical treatment may be a contributing problem.

Excessive use of antibacterial drops, leading to fungal infection.

Underlying skin disease.

Hearing aid, ear plugs, or anatomical problems, such as meatal stenosis.

If no cause is apparent, prescribe seven days of acetic acid 2% ear drops together with corticosteroid ear drops.

If fungal growth is suspected, a topical antifungal preparation such as clotrimazole 1% solution may be tried. Swabbing is recommended.

Treatment can be difficult and referral may be required in these circumstances.

Other therapies tried include tacrolimus.16

Necrotising otitis externa

Necrotising or malignant otitis externa is caused by P. aeruginosa in 90% of cases.17 Oral and topical treatment with quinolones (given for six to eight weeks) are usually required. Evolving resistance to ciprofloxacin can be a problem.18

If necrotising or malignant otitis externa is suspected, urgent referral to ENT should be made.

Otitis externa treatments5

Back to contentsTopical treatments

Topical drops are usually effective unless there is spread with cellulitis or the patient is systemically unwell. A 2021 systematic review found that topical preparations were prescribed for 77-95% of cases in primary care.19 In most cases the choice of topical intervention does influence the therapeutic outcome significantly.

Acetic acid is effective and comparable to antibiotic/steroid at week 1. However, when treatment needs to be extended beyond this it is less effective. It is therefore recommended for mild cases only.20

Evidence for steroid-only drops is very limited.

Topical antibiotics are recommended for all but the mildest cases. Laboratory sensitivities are not usually relevant, as testing is done using concentrations achieved in systemic dosing. Much higher concentrations of antibiotic are achieved with topical application. Virtually all of the bacteria recovered are sensitive to the concentrations of antibiotic present in topical ear medications. Choice is therefore determined by other factors, such as availability, risks of ototoxicity or contact sensitivity, cost and dosing schedule and the wish to limit development of bacterial resistance:

The British National Formulary (BNF) recommends neomycin or clioquinol (which also covers fungal infections).

Aminoglycosides are relatively contra-indicated if there is perforation of the eardrum, as they can be ototoxic: they are used cautiously as second-line. They can cause contact dermatitis, although rarely after a short course.

Recommended steroids are betamethasone, hydrocortisone, prednisolone, dexamethasone and flumetasone.

Risk of secondary fungal infection or allergy increases when courses are prolonged: contact sensitivity from topical drops is most commonly due to antibiotics (especially aminoglycosides) or preservatives.

If there is extensive swelling of the auditory canal, consider inserting an ear wick (may require ENT referral for assistance with aural toilet). It should be impregnated with antibiotic-steroid combination and is inserted into the auditory canal. It is sometimes soaked in an astringent such as aluminium acetate or steroid to reduce oedema of the ear canal:

Insertion usually requires referral.

The ear wick should be changed at least every two or three days.

If packing is not used, patients with a swollen ear canal should insert drops whilst lying on the other side with the affected ear up, maintaining this position for 10 minutes afterwards.

Peroxide drops have been a recommended 'home remedy' for swimmer's ear in the past. They dissolve wax and are acidifying and bactericidal. They have a preventative role but no published evidence could be found for peroxide drops as a treatment for active infection.

There has been some interest in tacrolimus as a topical treatment in chronic refractory otitis externa.21

Patients prescribed antibiotic/steroid drops can expect their symptoms to last for approximately six days after treatment has begun. They should use drops for at least a week. If they have symptoms beyond the first week they should continue the drops until their symptoms resolve, for a maximum of a further seven days.

Patients with persisting symptoms beyond two weeks should be considered treatment failures and alternative management initiated.

Aural toilet

If earwax or debris is likely to obstruct topical medication, cleaning the external auditory canal lowers pH and increases the activity of aminoglycoside ear drops. Gentle syringing or microsuction are the usual methods. This cleaning is felt to improve drug penetration and reduce the risk of future infections. This may be required several times a week.

Syringing is usually avoided if the tympanic membrane is not intact.

Systemic treatment

Oral antibiotics are not usually needed. They may be indicated if:

The patient is systemically unwell.

There is pre-auricular lymphadenopathy.

There is evidence of spreading infection.

The antibiotic of choice is flucloxacillin (or erythromycin if there is penicillin allergy) because infection is usually due to S. aureus.

A systematic review found that when oral antibiotics were prescribed empirically it was most likely to be amoxicillin/clavulanic acid which would not cover the typical bacteria found in these infections.19

Advice on self-care

Remove or treat aggravating factors.

Advise patients to keep the ear dry and to use buds or ear plugs.

Avoid cotton wool to plug the discharging ear unless discharge is so profuse that it is required for cosmetic reasons. If used, keep it loose and change often.

Avoid swimming and, until settled, try to prevent water from entering the ear.

Complications15

Back to contentsTemporary hearing loss or muffling.

Acute otitis externa may become chronic. An outer ear infection is usually considered chronic if signs and symptoms persist for more than three months. Chronic infections are more common if there are conditions that make treatment difficult, such as a rare strain of bacteria, an allergic skin reaction, an allergic reaction to antibiotic eardrops, or a combination of a bacterial and fungal infection.

Deep tissue infection (cellulitis). Rarely, otitis externa may result in the spread of infection into deep layers and connective tissues of the skin.

Bone and cartilage damage (necrotising otitis externa). Infection spreads to the skin and cartilage of the outer ear and bones of the lower part of the skull, causing increasingly severe pain. It may involve the mastoid and there may be facial nerve palsy. Older adults and those with diabetes or immunosuppression are at increased risk. Necrotising otitis externa is also known as malignant otitis externa but it is not a malignancy.

If swimmer's ear develops into necrotising otitis externa, haematogenous extension leading to sepsis may result. This rare complication can be life-threatening.

Referral5

Back to contentsAdmit urgently if malignant otitis is suspected. Suspect malignant otitis if:

Pain and headache are more severe than the clinical signs would suggest; or

There is granulation tissue at the bone-cartilage junction of the ear canal, or exposed bone in the ear canal; or

The facial nerve is paralysed (drooping of the face on the side of the lesion).

Consider seeking specialist advice if:

Symptoms have not improved despite treatment and treatment failure is unexplained.

Treatment with a quinolone is indicated.

Consider referral to secondary care if there is:

Extensive cellulitis.

Extreme pain or discomfort.

Considerable discharge or extensive swelling of the auditory canal and microsuction or ear wick insertion is required.

Prognosis5

Back to contentsMost cases of otitis externa resolve within a few days of starting treatment. The condition will tend to recur unless underlying causative factors are addressed.

Follow-up

Back to contentsTwo groups require specific follow-up:

Patients with recurrent infections who may have an underlying cholesteatoma. These patients must have full visualisation of the tympanic membrane, which may only be possible following microsuction.

Patients who may have underlying systemic disease predisposing to persistent symptoms.

Prevention of otitis externa

Back to contentsPrevention of otitis externa relies upon minimising the underlying causative factors. Patients can be advised:

A dry ear is unlikely to become infected, so it is important to keep the ears free of moisture during swimming or bathing and to tip out any liquid after swimming/bathing.

Use ear plugs when swimming.

Avoid swimming in stagnant or contaminated water.

Use a dry towel or hair dryer to dry the ears.

Have ears cleaned periodically if flaky or scaly, or if there is excessive earwax.

Do not use cotton swabs to remove wax. They pack wax and dirt deeper into the ear canal, remove the protective layer of earwax further out and disturb the lining, creating an ideal environment for infection.

Swimmers sometimes try acidifying swimmer's ear drops before and after swimming. Mixtures which have been tried include:

One part of white vinegar with one part of rubbing alcohol (one teaspoon into each ear, drained after ten minutes).

3% peroxide solution (about half of an ear dropper full into the ear, allowed to fizz and tipped out). In addition to dissolving cerumen, this has bactericidal properties, although some clinicians think that peroxide may damage healthy tissue, so it has fallen somewhat out of favour.

Olive oil or proprietary wax drops to reduce wax build-up (which may trap water) can also be helpful.

Dr Mary Lowth is an author or the original author of this leaflet.

Further reading and references

- Smith ME, Hardman JC, Mehta N, et al; Acute otitis externa: Consensus definition, diagnostic criteria and core outcome set development. PLoS One. 2021 May 14;16(5):e0251395. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0251395. eCollection 2021.

- Necrotising otitis externa; ENT UK Guidelines, May 2020

- Wipperman J; Otitis externa. Prim Care. 2014 Mar;41(1):1-9. doi: 10.1016/j.pop.2013.10.001. Epub 2013 Dec 7.

- Mady OM, El-Ozairy HS, Wady EM; Increased incidence of otitis externa in covid-19 patients. Am J Otolaryngol. 2021 May-Jun;42(3):102672. doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2020.102672. Epub 2020 Aug 11.

- Wiegand S, Berner R, Schneider A, et al; Otitis Externa. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2019 Mar 29;116(13):224-234. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2019.0224.

- Raza SA, Denholm SW, Wong JC; An audit of the management of acute otitis externa in an ENT casualty clinic. J Laryngol Otol. 1995 Feb;109(2):130-3.

- Otitis externa; NICE CKS, May 2024 (UK access only)

- Hajioff D, MacKeith S; Otitis externa. BMJ Clin Evid. 2015 Jun 15;2015. pii: 0510.

- Schaefer P, Baugh RF; Acute otitis externa: an update. Am Fam Physician. 2012 Dec 1;86(11):1055-61.

- Liu Z, Slim MAM, Scally C; Otitis Externa in Secondary Care: A Change in Our Practice Following a Full Cycle Audit. Int Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2018 Jul;22(3):250-252. doi: 10.1055/s-0037-1606621. Epub 2017 Sep 19.

- Yariktas M, Yildirim M, Doner F, et al; Allergic contact dermatitis prevalence in patients with eczematous external otitis. Asian Pac J Allergy Immunol. 2004 Mar;22(1):7-10.

- Al Aaraj MS, Kelley C; Malignant Otitis Externa

- Soudry E, Joshua BZ, Sulkes J, et al; Characteristics and prognosis of malignant external otitis with facial paralysis. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007 Oct;133(10):1002-4.

- Arsovic N, Radivojevic N, Jesic S, et al; Malignant Otitis Externa: Causes for Various Treatment Responses. J Int Adv Otol. 2020 Apr;16(1):98-103. doi: 10.5152/iao.2020.7709.

- Vourexakis Z, Kos MI, Guyot JP; Atypical presentations of malignant otitis externa. J Laryngol Otol. 2010 Nov;124(11):1205-8. doi: 10.1017/S0022215110000307. Epub 2010 Mar 2.

- Chakraborty D, Bhattacharya A, Kamaleshwaran KK, et al; Single photon emission computed tomography/computed tomography of the skull in malignant otitis externa. Am J Otolaryngol. 2012 Jan-Feb;33(1):128-9. doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2011.05.002. Epub 2011 Jul 20.

- Medina-Blasini Y, Sharman T; Otitis Externa. StatPearls, Jan 2024.

- Kesser BW; Assessment and management of chronic otitis externa. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2011 Oct;19(5):341-7. doi: 10.1097/MOO.0b013e328349a125.

- Rubin Grandis J, Branstetter BF 4th, Yu VL; The changing face of malignant (necrotising) external otitis: clinical, radiological, and anatomic correlations. Lancet Infect Dis. 2004 Jan;4(1):34-9.

- Chen YA, Chan KC, Chen CK, et al; Differential diagnosis and treatments of necrotizing otitis externa: a report of 19 cases. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2011 Dec;38(6):666-70. doi: 10.1016/j.anl.2011.01.020. Epub 2011 Feb 24.

- Mughal Z, Swaminathan R, Al-Deerawi HB, et al; A Systematic Review of Antibiotic Prescription for Acute Otitis Externa. Cureus. 2021 Mar 27;13(3):e14149. doi: 10.7759/cureus.14149.

- Kaushik V, Malik T, Saeed SR; Interventions for acute otitis externa. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010 Jan 20;(1):CD004740.

- Caffier PP, Harth W, Mayelzadeh B, et al; Tacrolimus: a new option in therapy-resistant chronic external otitis. Laryngoscope. 2007 Jun;117(6):1046-52.

Continue reading below

Article history

The information on this page is written and peer reviewed by qualified clinicians.

Next review due: 29 May 2027

30 May 2022 | Latest version

Ask, share, connect.

Browse discussions, ask questions, and share experiences across hundreds of health topics.

Feeling unwell?

Assess your symptoms online for free