Rubella

Peer reviewed by Dr Hayley Willacy, FRCGP Last updated by Dr Colin Tidy, MRCGPLast updated 13 Jun 2023

Meets Patient’s editorial guidelines

- DownloadDownload

- Share

- Language

- Discussion

- Audio Version

Medical Professionals

Professional Reference articles are designed for health professionals to use. They are written by UK doctors and based on research evidence, UK and European Guidelines. You may find the Rubella article more useful, or one of our other health articles.

In this article:

Synonym: German measles

This disease is notifiable in the UK - see NOIDs article for more detail.

Continue reading below

What is rubella?

Rubella is a viral infection once seen mainly in spring and early summer. Epidemics occur every six to nine years in populations with no vaccination programme.1 Before introduction of vaccination it was endemic in virtually all countries.

Rubella virus is spread from person to person via the respiratory route. Immunity following natural infection or vaccination is life-long. In the absence of vaccination, the mean age of rubella infection is 5–9 years of age. The cyclical nature of rubella is related to the build-up of susceptible persons in the population and contact rates.2

It is now quite rare in developed nations since the introduction of immunisation (see the separate article Measles, Mumps and Rubella (MMR) Vaccination). The vaccine is safe and vaccination is a very successful health intervention. However, more evidence is needed to assess whether the protective effect of MMR could wane with time since immunisation.3

In the absence of mass vaccination, approximately 10-20% of women reaching child-bearing age are susceptible to rubella.4

Pathophysiology

Back to contentsAn RNA virus (genus Rubivirus, family Togaviridae) with man as the only known host:

There is only one major antigenic type.

It is transmitted as airborne droplets between close contacts (unlike most togaviruses which are arthropod-borne).

The incubation period is 14-21 days with patients being infectious for up to seven days before and four days after symptoms appear.

Infectivity is greatest just before and on the day of symptoms appearing.

Its major complication of maternal infection in early pregnancy is congenital rubella syndrome (CRS) - see the separate article Rubella and Pregnancy:

This causes a wide variety of malformations affecting the cardiac, ocular, central nervous and skeletal systems when a pregnant mother is infected.

This is still a problem in many developing countries.

Continue reading below

How common is rubella? (Epidemiology)5

Back to contentsBefore the introduction of routine vaccination, rubella was common in the UK with most infections occurring in young children (5–9 years of age). More than 80% of adults had evidence of prior infection.

Since the MMR vaccine was introduced, rubella infection has become uncommon in the UK. In England and Wales the total number of laboratory confirmed cases of rubella was 5 in 2015, 2 in 2016 and 3 in 2017.

Worldwide, an estimated 100,000 cases of congenital rubella syndrome (CRS) occur each year.

As vaccination uptake and rubella immunity is relatively high in the UK, rubella infection in pregnancy is uncommon and CRS is very rare.

Pre-vaccination there were 200–300 CRS births during non-epidemic years and much higher numbers in epidemic years.

Most identified infections in pregnancy in the UK are acquired abroad and in unvaccinated women.

Rubella signs and symptoms (presentation)5 6

Back to contentsSymptoms

Prodromal phase of lassitude, low-grade fever, headache, mild conjunctivitis and anorexia with rhinorrhoea very similar to a cold. The prodrome may be absent in children and tends to be more noticeable in adults.

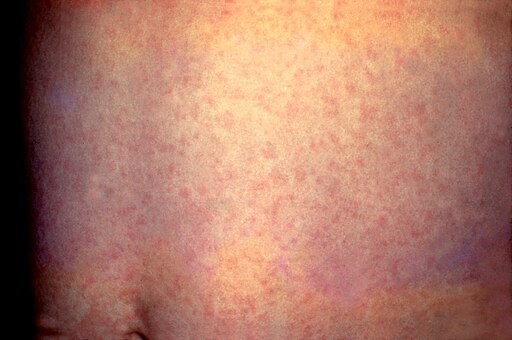

The rash then develops (it may be absent, especially in young children) - initially, pink discrete macules that coalesce, starting behind the ears and on the face, spreading to the trunk and then the extremities.

Cervical, suboccipital and postauricular lymphadenopathy are characteristic and may precede the rash.

Constitutional symptoms are usually mild (can be more prominent in adults).

In older patients, arthralgia is common.

Signs

There may be petechiae on the soft palate (Forchheimer's sign) but this is not diagnostic for rubella.

The rash is shown in close-up but it should be remembered that clinical diagnosis is unreliable.

The rash usually develops 14-17 days after exposure to the virus.

Rubella

© Photo Credit:Content Providers(s): CDC, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

By CDC, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Continue reading below

Differential diagnosis5

Back to contentsHerpesvirus type 6 (roseola infantum), enterovirus, adenovirus, cytomegalovirus, HIV, hepatitis, echovirus, coxsackievirus.

Tropical viruses including alphaviruses and flaviviruses (eg, West Nile virus, Dengue virus, Chikungunya virus, and Zika virus).

Other infections including scarlet fever, brucellosis, Kawasaki disease, syphilis, and toxoplasmosis.

Drug reactions, eg, mononucleosis reaction with amoxicillin and reaction to anti-epileptic drugs.

Investigations

Back to contentsClinical diagnosis is unreliable since symptoms are often fleeting and mimicked by other viruses. In particular, the rash is not diagnostic.

Serological and/or polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing is the gold standard investigation and the local Health Protection Unit (HPU) can provide a testing kit.5

FBC may show a low WBC count with an increased proportion of lymphocytes and thrombocytopenia (usually resolves in a month).

Management of rubella5

Back to contentsThere is no specific treatment.

Advise to stay away from school or work for at least 5 days after the initial development of the rash.

Use antipyretics for fever - avoid aspirin in children, due to the danger of Reye's syndrome.

Ask about any contact with pregnant women.

Where suspected infection occurs in a pregnant woman, it should be confirmed by investigation, in liaison with a virologist, and counselling should be given about the dangers to the fetus. Management requires referral and expert support.

Complications of rubella5

Back to contentsComplications occur rarely.

Rubella encephalopathy may occur about six days after the rash (usually there is full recovery in a few days without sequelae).

Arthritis and arthralgia can occur in adults.

Thrombocytopenia occurs in around 1 in 3,000 cases.

Guillain-Barré syndrome/neuritis.

Panencephalitis.

Prevention of rubella5

Back to contentsThe advice is to stay away from school or work for at least 5 days after the initial development of the rash.

Vaccination via MMR in the second year of life plus a preschool booster, with antenatal screening for rubella susceptibility.

Where non-immunity to rubella is discovered during pregnancy, immunisation after delivery offers protection for future pregnancies.

The vaccine has been proven to be safe, immunogenic and effective.7

The overall decline in rubella incidence and increase in the number of countries conducting rubella surveillance through a mandatory notification system are notable achievements toward the goal of rubella elimination in Europe.8

Rubella in pregnancy2 9

Back to contentsWhen infection with rubella occurs just before conception or during the first 8–10 weeks of gestation, it may cause multiple fetal defects in up to 90% of cases, including miscarriage or stillbirth.

The risk of birth defects declines with infection later in gestation, and fetal defects are rarely associated with maternal rubella after the 16th week of pregnancy, although sensorineural hearing deficit may occur with infection as late as week 20.

The defects associated with congenital rubella syndrome (CRS) most commonly affect the eyes (eg, cataracts, microphthalmia, glaucoma, pigmentary retinopathy, chorioretinitis), hearing (sensorineural deafness), the heart (eg, peripheral pulmonary artery stenosis, patent ductus arteriosus or ventricular septal defects), and the brain (eg, microcephaly).

Those that survive the neonatal period may face serious developmental disabilities (eg, visual and hearing impairments) and have an increased risk for developmental delay, including autism.

Congenital rubella infection has been associated with increased risk of endocrinopathies such as thyroiditis and insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus with associated long-term effects. A progressive encephalopathy resembling subacute sclerosing panencephalitis has also been observed in patients with CRS.

Further reading and references

- Rubella (German measles): guidance, data and analysis; GOV.UK. April 2013, last updated November 2022.

- Rubella fact sheet; World Health Organization (WHO)

- McLean H et al; Chapter 14 Rubella, Manual for the Surveillance of Vaccine-Preventable Diseases, 2014.

- Lambert N, Strebel P, Orenstein W, et al; Rubella. Lancet. 2015 Jun 6;385(9984):2297-307. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60539-0. Epub 2015 Jan 8.

- Di Pietrantonj C, Rivetti A, Marchione P, et al; Vaccines for measles, mumps, rubella, and varicella in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021 Nov 22;11(11):CD004407. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004407.pub5.

- Rubella vaccines: WHO position paper; World Health Organization, July 2020

- Rubella; NICE CKS, July 2023 (UK access only).

- Leung AKC, Hon KL, Leong KF; Rubella (German measles) revisited. Hong Kong Med J. 2019 Apr;25(2):134-141. doi: 10.12809/hkmj187785. Epub 2019 Apr 10.

- Davidkin I, Kontio M, Paunio M, et al; MMR vaccination and disease elimination: the Finnish experience. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2010 Sep;9(9):1045-53.

- Muscat M, Zimmerman L, Bacci S, et al; Toward rubella elimination in Europe: An epidemiological assessment. Vaccine. 2011 Dec 14.

- Mawson AR, Croft AM; Rubella Virus Infection, the Congenital Rubella Syndrome, and the Link to Autism. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019 Sep 22;16(19):3543. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16193543.

Continue reading below

Article history

The information on this page is written and peer reviewed by qualified clinicians.

Next review due: 12 May 2028

13 Jun 2023 | Latest version

Ask, share, connect.

Browse discussions, ask questions, and share experiences across hundreds of health topics.

Feeling unwell?

Assess your symptoms online for free