Salivary gland disorders

Peer reviewed by Dr Colin Tidy, MRCGPLast updated by Dr Laurence KnottLast updated 20 Dec 2021

Meets Patient’s editorial guidelines

- DownloadDownload

- Share

- Language

- Discussion

Medical Professionals

Professional Reference articles are designed for health professionals to use. They are written by UK doctors and based on research evidence, UK and European Guidelines. You may find the Salivary gland disorders article more useful, or one of our other health articles.

In this article:

What are salivary gland disorders?

Salivary gland problems may be due to infection, inflammation, obstruction or tumours. They may present with acute, chronic or recurrent symptoms. Usually a careful history and examination give initial clues as to the cause and ultrasound is generally the first line of investigation. All salivary gland swellings need urgent referral and investigation.

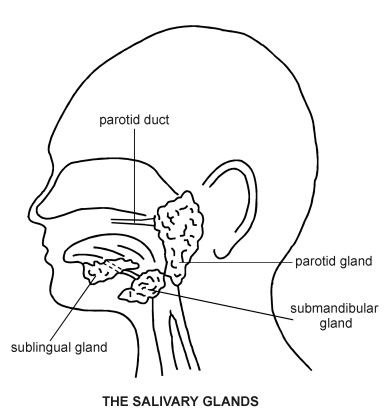

Salivary gland anatomy and physiology

Back to contentsApproximately 1-1.5 L/day of saliva are produced by three pairs of major salivary glands:

The parotid glands lie below the external auditory meatus, between the vertical ramus of the mandible and the mastoid process. The parotid duct crosses the masseter and opens via a small papilla on the buccal membrane opposite the crown of the second upper molar. The parotid gland has an intimate relationship with the facial nerve, which subdivides into its branches as it passes through the parotid.

The submandibular glands are walnut-sized paired structures, lying beneath and in front of the angle of the jaw, wrapping around the posterior edge of the mylohyoid muscle. Their ducts emerge to the floor of the mouth just lateral to the frenulum of the tongue.

The sublingual glands lie below the tongue and open through several ducts to the floor of the mouth.

There are also a large number (600-1,000) of minor salivary glands widely distributed throughout the oral mucosa, palate, uvula, floor of the mouth, posterior tongue, retromolar and peritonsillar area, pharynx, larynx and paranasal sinuses.

Saliva is made up of water, electrolytes, lubricants, antimicrobial compounds, enzymes and growth factors. Together, these components facilitate speech, mastication and swallowing, and start the process of digestion. Saliva also prevents oral problems by protecting the oral mucosa and teeth.

Salivary gland disorders

The major salivary glands

Continue reading below

Presentation

Back to contentsSalivary gland disorder symptoms

Ascertain the following from the history:

Which of the salivary glands is affected? Most commonly, it is the parotid. Conditions differentially affect the different salivary glands.

If there is swelling, is it unilateral or bilateral? Is it constant or does it come and go? Is the swelling painful? Pain may be referred to the ear or throat.

How long has the patient experienced symptoms? Has any mass increased in size since it was first noticed?

Are symptoms affected by eating?

Is there a feeling of dry mouth?

Are there systemic symptoms suggestive of infection, autoimmune disease, sarcoidosis or malignancy?

Is there anything of relevance in the current medical and dental history, or medication and immunisation record?

Signs

Examine the major salivary glands:

The parotid glands:

Swellings of the parotid are apparent as a loss of the angle of the jaw. The accessory lobe may also cause a lump anterior to the ear. The deep lobe needs to be inspected and palpated through the mouth. Swelling can displace the ipsilateral tonsil. Try to differentiate between generalised swelling of the gland, which tends to be due to obstruction of the duct or inflammatory disease, or localised lumps, which are more likely to be tumours.

Ask the patient to clench their teeth to allow palpation of the masseter. The anterior part of the parotid duct can be felt as it crosses the anterior border of the masseter muscle and occasionally a stone can be palpated in this part of the duct. Inspect the orifice of the duct in the mouth opposite the second upper molar by retracting the cheek with a spatula. Pressure on the body of the gland may lead to the extrusion of pus at the orifice in patients with parotitis.

Examine the facial nerve. Any facial weakness or asymmetry is highly suggestive of malignancy.

The submandibular glands:

Submandibular gland pathology usually involves swelling beneath and anterior to the angle of the jaw.

Inspect the orifices of the duct by asking the patient to lift their tongue to the roof of the mouth, noting the presence of inflammation or pus or indeed a visible impacted stone.

Examine bimanually with the index finger of one hand inside the mouth and fingers of the other hand over the outer surface of the lump in the neck. Under normal circumstances, the gland is not palpable but, if enlarged, can be felt 2-3 cm anterior to sternomastoid, below the horizontal ramus of the mandible. The gland has a rubbery consistency. The gland should not be fixed to the floor of the mouth or tongue. Check the course of the duct for a stone.

Sublingual gland pathology may cause swelling on the floor of the mouth.

Establish the following:

Is this swelling a salivary gland? Differentiating a swollen parotid gland and cervical lymphadenopathy may be very difficult clinically. Usually it is possible to feel in front of lymph nodes but it is impossible to get in front of the parotid. Similarly, attempt to differentiate between a submandibular swelling and superior cervical lymph nodes which are deep to sternomastoid.

Are there signs of systemic illness - eg, malaise, pyrexia?

Are the eyes dry? Look for keratoconjunctivitis sicca and for other features of Sjögren's syndrome, such as xerostomia and lingual papillary atrophy.

Has tooth enamel been lost? (This can be associated with the recurrent vomiting from bulimia.)

Is there any regional lymphadenopathy?

Terminology

Back to contentsSialadenitis refers to inflammation of a salivary gland and may be acute or chronic, infective or autoimmune.

Sialolithiasis refers to stone-related disease within the ductal systems of a gland.

Sialectasis refers to the dilation of a duct due to stones or strictures.

Sialadenosis refers to non-neoplastic non-inflammatory swelling with acinar hypertrophy and ductal atrophy.

Continue reading below

Causes of salivary gland disorders

Back to contentsIn the parotid glands, these include:

Stone in salivary duct.

Sarcoidosis (note, Heerfordt's syndrome = sarcoidosis with parotid enlargement, fever, anterior uveitis, and facial nerve palsy).

Acute and chronic bacterial parotitis.

In the submandibular glands:

Stone in the salivary duct.

Benign and malignant tumours.

Sjögren's syndrome (less common).

In the minor salivary glands:

Mucoceles.

Benign and malignant tumours.

Salivary gland infection1

Back to contentsMumps is the most common cause of salivary gland infection, although with widespread immunisation its incidence has fallen. It usually causes bilateral swelling of the parotid glands, although it may be unilateral and the other major salivary glands may also be affected in about 10% of cases2 3 . The swelling lasts around a week, accompanied by low-grade pyrexia and general malaise. See the separate Mumps article for more details.

Other viruses that may acutely infect the salivary glands include Coxsackievirus, parainfluenza, influenza A, parvovirus B19 and herpes.

Acute bacterial infection of the major salivary glands occurs usually in debilitated or dehydrated patients. Comorbidity and/or medication may inhibit saliva production, increasing vulnerability. Prior to the advent of antibiotics and intravenous fluid rehydration, bacterial parotitis had a high mortality rate. Infection ascends from the oral cavity, most frequently Staphylococcus aureus.

Chronic bacterial infection may occur on a background of a salivary gland previously damaged by stones, irradiation or autoimmune disease. Chronic infection destroys the glandular elements of the salivary glands and can impair the protective functions of saliva, leading to dental infections and disease. It consequently often first presents to a dentist.

Recurrent parotitis of childhood. Recurrent episodes of swelling and pain of the parotid gland with fever and pain, the cause of which is unknown.

Parotid swelling may be an initial presentation of HIV infection, and oral mucoceles and ranulas may also be a manifestation4 5 .

Tuberculosis is a rare cause of parotitis and other salivary gland swelling but should be considered in the differential in someone who is immunosuppressed or from a high-risk population6 .

Presentation

Swelling which is usually painful and tender.

Dry mouth.

Abnormal or foul tastes associated with purulent discharge from salivary duct opening (bacterial infection).

Mouth or facial pain, especially associated with eating.

Decreased mouth opening, difficulty talking.

Fever/systemically unwell.

Investigation

May include:

Blood tests - FBC, inflammatory markers, U&Es, blood culture, viral serology or salivary antibody testing, HIV test, as appropriate.

Pus swab for culture and sensitivities. (Massage the gland to express if needed.)

Sialography.

Ultrasound.

CT/MRI scan - often to exclude neoplasm.

Fine-needle aspirate or incisional biopsy for histology or culture material where relevant.

Salivary gland infection treatment and management

Mumps is a self-limiting condition without serious sequelae in most patients. Supportive treatment is appropriate. It remains a notifiable disease in the UK.

Acute suppurative infection is treated with antibiotics and incision and drainage if an abscess has developed.

Salivary flow should be encouraged by using warm compresses, sialagogues such as lemon drops, gum or vitamin C lozenges, hydration, salivary gland massage and oral hygiene.

With chronic infections, where duct obstruction is identified, stones or strictures can be removed, promoting saliva flow. Gland excision may sometimes be required where problems become recurrent.

NB: diseases of the salivary glands are rare in children (with the exception of acute parotitis usually due to mumps), so that any acute or chronic sialadenitis not responding to conservative treatment should be referred for specialist opinion7 .

Parotid gland chemodenervation with botulinum toxin has been shown to be effective as a minimally invasive option for symptomatic chronic sialadenitis refractory to medical treatment or sialendoscopy8 .

Complications

Complications of mumps parotitis include orchitis, oophoritis, aseptic meningitis and deafness. It is also (rarely) associated with sialectasia and recurrent sialadenitis .

Abscess formation with spread to the other deep neck spaces of the neck is the most concerning. Trismus may indicate parapharyngeal involvement. Ludwig's angina, where infection of the submental and sublingual spaces occurs, is rare but life-threatening.

Prevention

To prevent acute suppurative parotitis, consider risk factors, avoid anticholinergics and other drugs likely to disrupt saliva flow in the vulnerable and maintain good hydration and mouth care perioperatively and amongst critically ill patients. Mouth care is an important consideration in the care of the terminally ill.

A high uptake of measles, mumps and rubella (MMR) vaccine is essential to ensure herd immunity and prevent resurgence of mumps.

Salivary gland obstruction9

Back to contentsCalculi or stones can form in the major salivary glands and their ducts, causing obstruction of salivary outflow, typically with pain and swelling at mealtimes. This is most commonly seen in the submandibular gland and its duct (80-90%) but may also be seen in the parotid glands. Salivary gland obstruction is less common in the parotid gland, as its secretions are more watery and the duct is wider. Sublingual glands drain into 8-20 ducts so rarely obstruct.

Obstruction of minor salivary glands also occurs, resulting in cyst-like swellings in the lips and cheeks.

The cause of salivary gland stones is unknown. Stones are composed of mucus, cellular debris, calcium and magnesium phosphates.

Parotid gland obstructions are more usually due to stenosis of the opening of the duct rather than stones. This can sometimes be secondary to chronic trauma due to ill-fitting dentures.

Obstruction of a salivary duct causes inflammation and swelling of the gland.

If the salivary gland obstruction is not relieved, the gland becomes damaged and may ultimately require complete excision.

Salivary stones account for half of salivary gland disorders in the UK, with 5.9 cases per 100,000 people each year.

Presentation

Usually, colicky postprandial swelling of the gland.

Symptoms typically relapse and remit.

Investigation

Ultrasound - stones appears as markedly hyperechoic lines or points with distal acoustic shadowing. Ultrasound is now the first-line investigation and excludes other causes of swelling such as malignancy or lymphadenopathy.

Contrast sialography provides information about the ductal system and obstruction is indicated by filling defects or strictures.

CT scan.

Salivary gland obstruction treatment and management

Many stones will pass spontaneously so conservative treatment may consist of oral analgesics and antibiotics where there is infection. Good hydration, warm compresses and gland massage may assist the stone's passage.

Surgical management:

Proximal submandibular stones may be removed by dilating/incising Wharton's duct and a transoral approach.

Calculi in the submandibular duct may be removed by an incision in the floor of the mouth, whilst those in the substance of the gland may require gland excision.

Sialendoscopy assisted by CT navigation or lithotripsy are now more usually used where possible with the aim of better preserving gland function10 11 .

Prevention

Those who have had salivary calculi are more likely to produce them again. There are no evidence-based methods of prevention currently. Maintaining good hydration will aid saliva production and may reduce the risk of recurrence.

Sialadenosis9

Back to contentsSialadenosis is a generalised salivary gland swelling caused by hypertrophy of the acinar component of the gland. It is associated with a number of systemic diseases. Treatment for sialadenosis is aimed at the underlying cause. The most common degenerative disease affecting the salivary glands is Sjögren's syndrome, an autoimmune condition. See the separate Sjögren's Syndrome article.

It preferentially affects the parotid gland but may also affect the submandibular and minor salivary glands. It usually also affects the lacrimal glands.

Sjögren's syndrome may be accompanied by other systemic diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus or primary biliary sclerosis.

Sjögren's syndrome has a strong female-to-male predominance (9:1) and onset is typically in middle age.

Other causes of sialadenosis include:

Bulimia.

Anorexia.

Endocrine disorders such as Cushing's syndrome, diabetes mellitus and hypothyroidism.

Coeliac disease and malnutrition.

Alcoholism.

Drug-induced - eg, thiourea, anticholinergics.

Sarcoidosis and Heerfordt's syndrome.

Investigations

Sjögren's syndrome shows a characteristic sialectasis and parenchymal destruction on sialogram and may be confirmed through many different tests including:

Biopsy of the labial salivary glands.

Autoantibodies - Sjögren's syndrome A (SS-A) and Sjögren's syndrome B (SS-B).

Rheumatoid factor (positive in about 90%).

Antinuclear antibodies.

If sarcoidosis is suspected, CXR may show bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy. Other investigations depend on the overall clinical picture.

Sialadenosis treatment and management

In patients with Sjögren's syndrome, where the diagnosis is suspected, refer to rheumatology. Good dental care is essential to prevent caries. Parasympathetic drugs, such as pilocarpine, may be used for the treatment of hyposalivation and xerostomia. There is inadequate evidence currently to recommend local stimulants, lubricants and protectants, despite the widespread use of these products for symptomatic relief12 . Gland excision is rarely indicated.

Complications

The risk of malignant non-Hodgkin's lymphoma is increased in primary Sjögren's syndrome13 . It may be problematic to diagnose this in the context of persistent parotid swelling.

Salivary gland tumours9

Back to contentsMalignant tumours of the salivary glands are rare, with most neoplasms being benign.

Red flags

Rapid increase in the size of the swelling.

Ulceration and/or induration of the mucosa or skin.

Fixation to the skin.

Paraesthesia/anaesthesia of associated sensory nerves.

Past history of skin cancer, Sjögren's syndrome or radiation to the head and neck.

All salivary swellings, however, need urgent referral and investigation.

Investigation

Ultrasound is the first-line investigation, usually combined with fine-needle aspiration for cytology or core needle biopsy where a tumour is seen. MRI gives more information about tumour margins and staging, while CT scans and positron emission tomography-CT (PET-CT) are used to determine metastatic spread.

Salivary gland tumour treatment and management

Tumours generally require surgical excision. Postoperative radiotherapy may be required for malignant salivary gland tumours.

For further details, see the separate Salivary Gland Tumours article.

Further reading and references

- Wilson KF, Meier JD, Ward PD; Salivary gland disorders. Am Fam Physician. 2014 Jun 1;89(11):882-8.

- Mumps; NICE CKS, December 2023 (UK access only)

- Mumps: guidance, data and analysis; GOV.UK

- Ebrahim S, Singh B, Ramklass SS; HIV-associated salivary gland enlargement: a clinical review. SADJ. 2014 Oct;69(9):400-3.

- Syebele K, Butow KW; Oral mucoceles and ranulas may be part of initial manifestations of HIV infection. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2010 Oct;26(10):1075-8. Epub 2010 Sep 23.

- Tauro LF, George C, Kamath A, et al; Primary tuberculosis of submandibular salivary gland. J Glob Infect Dis. 2011 Jan;3(1):82-5.

- Ellies M, Laskawi R; Diseases of the salivary glands in infants and adolescents. Head Face Med. 2010 Feb 15;6:1.

- Strohl MP, Chang CF, Ryan WR, et al; Botulinum toxin for chronic parotid sialadenitis: A case series and systematic review. Laryngoscope Investig Otolaryngol. 2021 May 2;6(3):404-413. doi: 10.1002/lio2.558. eCollection 2021 Jun.

- Mehanna H, McQueen A, Robinson M, et al; Salivary gland swellings. BMJ. 2012 Oct 23;345:e6794. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e6794.

- Koch M, Zenk J, Iro H; Algorithms for treatment of salivary gland obstructions. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2009 Dec;42(6):1173-92, Table of Contents.

- Anicin A, Urbancic J; Sialendoscopy and CT navigation assistance in the surgery of sialolithiasis. Radiol Oncol. 2021 Aug 10;55(3):284-291. doi: 10.2478/raon-2021-0015.

- von Bultzingslowen I, Sollecito TP, Fox PC, et al; Salivary dysfunction associated with systemic diseases: systematic review and clinical management recommendations. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2007 Mar;103 Suppl:S57.e1-15.

- Zenone T; Parotid gland non-Hodgkin lymphoma in primary Sjogren syndrome. Rheumatol Int. 2011 Mar 23.

Continue reading below

Article history

The information on this page is written and peer reviewed by qualified clinicians.

Next review due: 19 Dec 2026

20 Dec 2021 | Latest version

Ask, share, connect.

Browse discussions, ask questions, and share experiences across hundreds of health topics.

Feeling unwell?

Assess your symptoms online for free