Spondylolisthesis and spondylolysis

Peer reviewed by Dr Laurence KnottLast updated by Dr Colin Tidy, MRCGPLast updated 20 Nov 2021

Meets Patient’s editorial guidelines

- DownloadDownload

- Share

- Language

- Discussion

Medical Professionals

Professional Reference articles are designed for health professionals to use. They are written by UK doctors and based on research evidence, UK and European Guidelines. You may find the Cervical spondylosis article more useful, or one of our other health articles.

In this article:

What is spondylolisthesis?

Spondylolisthesis is the movement of one vertebra relative to the others in either the anterior or posterior direction due to instability. Degenerative spondylolisthesis is a common pathology, often causing lumbar canal stenosis.1

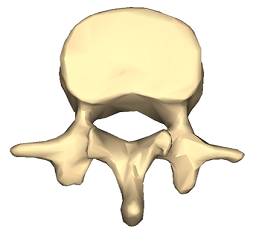

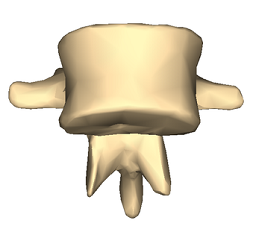

Anatomy of the vertebrae

The vertebrae can be divided into three portions:

Centrum - involved in weight bearing. This is the body of the vertebra and is formed of cancellous bone.

Dorsal arch - surrounds and protects the spinal cord. It carries the upper and lower facet joints of each vertebra which articulate with the facet joints of the vertebra above and below, respectively. The part of the vertebral arch between them is the thinnest part and is called the pars interarticularis, or the isthmus.

Posterior aspect - protrudes and can be palpated on the lower back.

Lumbar vertebra 1 inferior surface

© Anatomography, via Wikimedia Commons

Lumbar vertebra 1 anterior surface

© Anatomography, via Wikimedia Commons

Images by Anatomography, via Wikimedia Commons. Click here to see a lumbar vertebra 1 close-up superior surface animation.

Types of spondylolisthesis2

Back to contentsStable or unstable.

Asymptomatic or symptomatic.

Graded according to degree of slippage; the Meyerding classification is based on the ratio of the overhanging part of the superior vertical body to the anterio-posterior length of the inferior vertebral body:

Grade I: 0-25%.

Grade II: 26-50%.

Grade III: 51-75%.

Grade IV: 76-100%.

Grade V (spondyloptosis): >100%.

Graded according to type; the Wiltse classification (1976):

Type I: dysplastic (congenital).

Type II: isthmic: secondary to a lesion involving the pars interarticularis:

Subtype A: secondary to stress fracture.

Subtype B: result of multiple healed stress fractures resulting in an elongated pars.

Subtype C: acute pars fracture (rare).

Type III: degenerative.

Type IV: post-traumatic: fracture in a region other than the pars.

Type V: pathological: diffuse or local disease.

Type VI: iatrogenic.

Continue reading below

Spondylolisthesis vs spondylolysis

Back to contentsSpondylolysis and spondylolisthesis are separate conditions, although spondylolysis often precedes spondylolisthesis.

Spondylolysis is a bony defect (commonly due to a stress fracture but it may be a congenital defect) in the pars interarticularis of the vertebral arch, separating the dorsum of the vertebra from the centrum. It may occur unilaterally or bilaterally. It most commonly affects the fifth lumbar vertebra and may cause back pain.

Spondylolisthesis refers to the anterior slippage of one vertebra over another (or the fifth vertebra over the sacrum). There are five forms:

Isthmic: the most common form, usually acquired in adolescence as a consequence of spondylolysis but often unnoticed until adulthood.

Degenerative: developing in older adults as a result of facet joint osteoarthritis and bone remodelling.

Traumatic (rare): resulting from fractures of the neural arch.

Pathologic: from metastases or metabolic bone disease.

Dysplastic: (rare): congenital, resulting from malformation of the pars.

Spondylosis is a general term for degenerative osteoarthritic changes in the spine. It involves dehydration of the intervertebral discs with consequent narrowing of the intervertebral spaces. There may be changes in the facet joints with osteophyte formation and this may put pressure on the nerve roots, causing motor and sensory disturbance.

How common is spondylolisthesis and spondylolysis? (Epidemiology)2

Back to contentsSpondylolysis is a common diagnosis with a high prevalence in children and adolescents complaining of low back pain.

There is an increased risk of spondylolysis in young athletes like gymnasts, presumably due to impact-related stress fractures. However most cases are low-grade. At-risk activities include gymnastics, diving, tennis, cricket, weightlifting, football and rugby.

Isthmic spondylolisthesis affects around 5% of the population but is more common in young athletes. 60-80% of people with spondylolysis have associated spondylolisthesis.3 4

The majority of cases of spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis affect L5 and most of the remainder affect L4.

Degenerative spondylolisthesis is more common in older people, particularly women.

Traumatic, metastatic and dysplastic spondylolistheses are relatively rare.

Many cases of spondylolisthesis are asymptomatic.

Continue reading below

Spondylolisthesis causes (aetiology)

Back to contentsSpondylolisthesis commonly occurs due to a fracture or defect in the pars interarticularis, the narrowest part of the posterior vertebral arch between the upper and lower facet joints. When this is breached, the upper facet joint may no longer be able to hold the vertebra in place against the downward force of body weight and forward/downward slippage occurs.

Risk factors for spondylolisthesis

Risk factors that increase the risk of spondylolysis developing into spondylolisthesis include5 :

Female gender.

Young age.

Presence of spina bifida or spina bifida occulta.

Vertebral wedging.

Hyperlordosis.

Positive family history.

Certain high-impact sports, as evidenced by increased rates in athletes and gymnasts.3

Symptoms of spondylolisthesis (presentation)4

Back to contentsSpondylolisthesis symptoms

Presentation varies slightly by type although common spondylolisthesis symptoms include exercise-related back pain, radiating to the lower thighs, which tends to be eased by rest, particularly in positions of spinal flexion.

Isthmic spondylolisthesis

Most patients are asymptomatic, even with progressing slippage.

Symptoms often begin around the adolescent growth spurt.

Back pain - worse with activity (particularly back extension) - this may come on acutely or insidiously.

Pain may flare with sudden or trivial activities and is relieved by resting.

Pain is worse with higher grades of disease.

Pain may radiate to buttocks or thighs

There are usually no neurological features with lower grades of slippage but radicular pain becomes common with larger slips. Pain below the knee due to nerve root compression or disc herniation would suggest more severe slippage. High degrees of spondylolisthesis may present with neurogenic claudication or even cauda equina impingement.

Tightened hamstrings are very common

There may be enhanced lordosis and a waddling gait with shortened step length.

There may be gluteal muscular wasting.

Degenerative spondylolisthesis

Pain is aching in nature and insidious in onset.

Pain is in the low back and posterior thighs.

Neurogenic claudication may be present with lower-extremity symptoms worsening with exercise.

Symptoms are often chronic and progressive, sometimes with periods of remission.

If lumbar stenosis is also present, reflexes may be diminished.

Dysplastic spondylolisthesis

Presentation and physical findings are similar to isthmic spondylolisthesis but with a greater likelihood of neurological compromise.

Traumatic spondylolisthesis

Patients will have experienced acute trauma and are likely to have significant pain.

Severe slips may cause cauda equina compression with bladder and bowel dysfunction, radicular symptoms or neurogenic claudication.

Physical findings are as for the other types.

Pathological spondylolisthesis

Symptoms may be insidious in onset and associated with radicular pain.

Physical findings are as for the other types.

Spondylolysis symptoms

Most cases of spondylolysis are asymptomatic and identified incidentally.

It may present with low back pain provoked by lumbar extension, paraspinal spasm and tight hamstrings.

It frequently does not show on X-ray. It is important to consider it in the differential diagnosis of back pain, as its identification can prevent progression and avoid the potential need for aggressive intervention.

Differential diagnosis

Back to contentsOther causes of back pain need to be ruled out such as:

Spinal cord lesion.

Diagnosing spondylolisthesis (investigations)

Back to contentsBlood tests - looking for infection, myeloma, hypercalcaemia/hypocalcaemia.

Lateral spinal X-rays - will show spondylolisthesis. These are best performed in the position of maximal pain.

Oblique spinal X-rays - may (but will often not) detect spondylolysis.

Radionuclide scintigraphy and CT may help in cases of spondylolysis in distinguishing progressing lesions of the pars from stable lesions.

MRI is often performed perioperatively to look at relationships between the bony and neurological structures in the compromised area.

Spondylolisthesis treatment and management1 2 4

Back to contentsThe goal of treatment is to relieve pain, stabilise the spinal segment and stop or reverse the slippage. Patients need to be evaluated for the presence of instability, as if there is an unstable segment early surgery will be needed.

Depending on the severity of the spondylolysis and symptoms associated it may be treated either conservatively or surgically, both of which have shown significant success.

Conservative treatments such as bracing and decreased activity have been shown to be most effective with patients who have early diagnosis and treatment. Low-intensity pulsed ultrasound in addition to conservative treatment appears to achieve a higher rate of bony union. Surgery may be required if conservative treatment, for at least six months, failed to give sustained pain relief for the activities of daily living.

For degenerative spondylolisthesis, surgery is indicated mainly for perceived functional impairment. Improvement in neurological symptoms is one of the main treatment objectives. For this, it is useful to perform radicular decompression. The most frequent technique is direct posterior decompression.

Conservative treatment

Complete bed rest for 2-3 days can be helpful in relieving pain, particularly in spondylolysis, although longer periods are likely to be counterproductive. Patients should try to sleep on their side as much as possible, with a pillow between the knees.

Activity modification to prevent further injury. This may mean avoidance of activities if there is >25% slippage.

Analgesia - eg, paracetamol, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), codeine phosphate.

Steroid and local anaesthetic injections are sometimes used around compressed nerve roots or even into the fracture area of the pars for diagnostic purposes.

Bracing: a brace or corset may be recommended for a pars interarticularis fracture which is likely to heal. Bracing with exercise may be beneficial for patients with mild or even more severe degrees of slippage.

Physiotherapy: this includes massage, ultrasound, bracing, mobilisation, biomechanical correction, hydrotherapy, exercises for flexibility, strength and core stability and a gradual return to activity programme.

More than 80% of children treated non-surgically will have full resolution of symptoms.

A meta-analysis of observation studies suggested that around 80% of all patients treated non-operatively would have a successful clinical outcome after one year. Lesions diagnosed at the acute stage and unilateral lesions were the best subgroups.6

Surgical treatment

If there is evidence of progression or if conservative measures are ineffective then surgical therapy may be offered. This depends also on degree and aetiology.

Surgical intervention involves a prolonged rehabilitation period so it is generally not considered until conservative treatments have failed. An exception would be in the case of significant instability or neurological compromise and in high-grade slips.

Surgical therapy involves fusing the affected vertebra with a neighbouring normally aligned vertebra (both anteriorly and posteriorly). The intervertebral disc is usually also removed, as it is inevitably damaged. The slipped vertebra may be realigned.

Whilst most surgeons agree that decompression of the nerves is of benefit to patients, the benefit of realigning slipped vertebrae is uncertain. For example, when the spondylolisthesis is very gradual in onset, or in cases of congenital spondylolisthesis, compensatory changes in the spine and musculature occur so that realignment may increase the possibility of further injury.

There is good evidence that surgical treatment of symptomatic spondylolisthesis is significantly superior to non-surgical management in the presence of:7

Significant neurological deficit.

Failed response to conservative therapy.

Instability with neurological symptoms.

Degree of subluxation of III or more.

Unremitting pain affecting quality of life.

A large systematic review concluded that reduction of displacement carried benefits over fusion alone, although a large retrospective review showed high complication rates, particularly for older patients with more severe disease.8 9 10 11

Fusion techniques can be associated with neurological complications in older patients with degenerative spondylolisthesis, but in adolescent patients outcomes are good.9

Surgery is commonly complicated by pseudoarthrosis (non-union) which may result in chronic pain years down the line.

In the case of spondylolysis, if surgery is offered it would involve pinning the defect. However, most cases are managed conservatively.

Complications of surgical repair

Back to contentsImplant failure.

Pseudoarthrosis (failure of bone healing leading to a 'false joint').

Poor alignment of the fusion.

Neurological damage: foot drop, spinal cord compression. Chronic nerve injury/inflammation: neuropathic pain can persist in the face of apparent surgical success, possibly due to permanent changes in the nerves or a deregulation of pain control mechanisms.

Spondylolisthesis prognosis

Back to contentsSpondylolisthesis is generally a benign condition; however, it runs a chronic course and is therefore a cause of much morbidity and disability. In degenerative spondylolisthesis this will relate in part to the progress and prognosis of the underlying changes.

Dr Mary Lowth is an author or the original author of this leaflet.

Further reading and references

- Guigui P, Ferrero E; Surgical treatment of degenerative spondylolisthesis. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2017 Feb;103(1S):S11-S20. doi: 10.1016/j.otsr.2016.06.022. Epub 2016 Dec 30.

- Gagnet P, Kern K, Andrews K, et al; Spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis: A review of the literature. J Orthop. 2018 Mar 17;15(2):404-407. doi: 10.1016/j.jor.2018.03.008. eCollection 2018 Jun.

- Toueg CW, Mac-Thiong JM, Grimard G, et al; Prevalence of spondylolisthesis in a population of gymnasts. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2010;158:132-7.

- Syrmou E, Tsitsopoulos PP, Marinopoulos D, et al; Spondylolysis: a review and reappraisal. Hippokratia. 2010 Jan;14(1):17-21.

- Sadiq S, Meir A, Hughes SP; Surgical management of spondylolisthesis overview of literature. Neurol India. 2005 Dec;53(4):506-11.

- Klein G, Mehlman CT, McCarty M; Nonoperative treatment of spondylolysis and grade I spondylolisthesis in children and young adults: a meta-analysis of observational studies. J Pediatr Orthop. 2009 Mar;29(2):146-56. doi: 10.1097/BPO.0b013e3181977fc5.

- Alfieri A, Gazzeri R, Prell J, et al; The current management of lumbar spondylolisthesis. J Neurosurg Sci. 2013 Jun;57(2):103-13.

- Weinstein JN, Lurie JD, Tosteson TD, et al; Surgical compared with nonoperative treatment for lumbar degenerative spondylolisthesis. four-year results in the Spine Patient Outcomes Research Trial (SPORT) randomized and observational cohorts. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009 Jun;91(6):1295-304. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.H.00913.

- Sansur CA, Reames DL, Smith JS, et al; Morbidity and mortality in the surgical treatment of 10,242 adults with spondylolisthesis. J Neurosurg Spine. 2010 Nov;13(5):589-93. doi: 10.3171/2010.5.SPINE09529.

- Kasliwal MK, Smith JS, Kanter A, et al; Management of high-grade spondylolisthesis. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 2013 Apr;24(2):275-91. doi: 10.1016/j.nec.2012.12.002. Epub 2013 Feb 21.

- Longo UG, Loppini M, Romeo G, et al; Evidence-based surgical management of spondylolisthesis: reduction or arthrodesis in situ. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014 Jan 1;96(1):53-8. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.L.01012.

Continue reading below

Article history

The information on this page is written and peer reviewed by qualified clinicians.

Next review due: 19 Nov 2026

20 Nov 2021 | Latest version

Ask, share, connect.

Browse discussions, ask questions, and share experiences across hundreds of health topics.

Feeling unwell?

Assess your symptoms online for free