Obstetric cholestasis

Peer reviewed by Dr Doug McKechnie, MRCGPLast updated by Dr Philippa Vincent, MRCGPLast updated 20 Oct 2024

Meets Patient’s editorial guidelines

- DownloadDownload

- Share

- Language

- Discussion

- Audio Version

In this series:Pregnancy complicationsUrine infection in pregnancyChickenpox contact in pregnancyRubella and pregnancyHigh blood pressure in pregnancyPre-eclampsia

Obstetric cholestasis is a rare condition. It only affects pregnant women. In the UK fewer than 1 in 100 pregnant women will develop it.

In this article:

Video picks for Pregnancy complications

Continue reading below

What is obstetric cholestasis?

'Obstetric' relates to the area of medicine caring for pregnant women.

'Cholestasis' means there is a slowing down of the flow of bile down the bile ducts in the liver. This slowing of the flow of bile leads to a build-up of bile and some then leaks out into the bloodstream, particularly the bile salts. Once in the bloodstream they can make the skin very itchy.

It is also sometimes called intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy (ICP) and this name is being used more often.

What causes obstetric cholestasis?

Back to contentsObstetric cholestasis is a problem that can occur with the way the liver works during pregnancy. To understand what obstetric cholestasis is, it is necessary to understand a little bit about how the liver works normally.

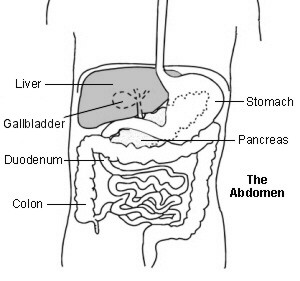

The liver is in the abdomen, on the upper right-hand side. The liver has many jobs including:

Storing fuel for the body.

Helping to process fats and proteins from digested food.

Making proteins that are needed for blood to clot properly.

Processing some medications.

Helping to remove toxins from the body.

Liver function

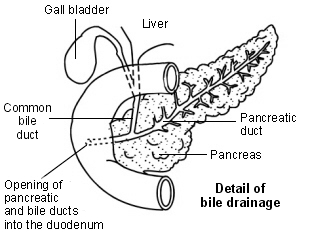

Pancreas - bile drainage

The liver also makes bile. Bile helps to break down (digest) fats in the gut. Bile is a greenish-yellow fluid which contains bile acids, bile pigments and waste products such as bilirubin. Liver cells pass bile into bile ducts inside the liver.

The bile flows down these ducts into larger and larger ducts, eventually leading to the common bile duct. The gallbladder is like a cul-de-sac reservoir of bile which comes off the common bile duct.

After eating, the gallbladder squeezes bile back into the common bile duct and down into the upper part of the gut (duodenum).

Exactly why obstetric cholestasis happens is not clear. Hormonal and genetic factors may be responsible:

Hormonal factors. Pregnancy causes an increase in oestrogen and progesterone hormones. These affect the liver and slow down the bile as it passes out along the tiny bile ducts. Some pregnant women may be more sensitive than others to these hormonal effects.

Genetic factors. Obstetric cholestasis seems to run in some families (although it may skip some generations). One theory is that women who develop obstetric cholestasis may have inherited a very slight problem with the way bile is made and passes down the bile ducts. This doesn't matter when they aren't pregnant but the high level of hormones made during pregnancy may tip the balance to slow down the flow of bile more significantly.

There may be other environmental factors which play a part. Whatever the underlying cause, pregnancy triggers the problem. Within a week or so after giving birth the symptoms stop and there is no long-term problem with the liver.

Continue reading below

What are the symptoms of obstetric cholestasis?

Back to contentsThe most common symptom is a really bad itch. There is not a skin rash but there may be marks on the skin from scratching. The itch can be all over, although it is often particularly bad on the hands and feet. It is often worst at night.

Usually itch is the only symptom. The itch tends to get worse until the baby is delivered. The itch can become so severe that it affects sleep, concentration and mood. It can be very distressing.

Typically, symptoms start after 24 weeks of your pregnancy, when the hormone levels are at their highest. Sometimes it can develop earlier in pregnancy.

Note: mild itching from time to time is normal in pregnancy. However, if you develop a constant itch that gets worse, it is very important to inform your midwife. A blood test can confirm if you have obstetric cholestasis.

Other less common symptoms include:

Tiredness.

Reduced appetite and feeling sick.

Mild jaundice: this can result in a yellow skin, dark urine and pale stools. This is uncommon and due to an increased level of bilirubin (part of bile) leaking from the bile ducts into the bloodstream. See the separate leaflet called Jaundice for more details.

A rash is not a symptom of cholestatic jaundice. Medical advice should be sought for any unusual rash in pregnancy.

Who gets obstetric cholestasis?

Back to contentsObstetric cholestasis is a rare condition that only affects pregnant women. In the UK, fewer than 1 in 100 pregnant women will develop obstetric cholestasis.

It is more common in women from certain ethnic groups, such as South Asians and Mapuche (indigenous people in southern Chile and southwestern Argentina). It affects about 1 in 67 pregnancies in women of South Asian origin. In certain parts of the world, particularly in Chile and Bolivia, at least 1 in 20 pregnant women develop this condition. It is also more common in women carrying twins, triplets, or more babies.

Mothers, daughters and sisters of women who have had obstetric cholestasis have a higher than average risk of also being affected when pregnant. Obstetric cholestasis in one pregnancy increases the chance that it will happen again in future pregnancies.

Continue reading below

What are the risks with obstetric cholestasis?

Back to contentsThe vast majority of women with obstetric cholestasis have a normal healthy baby. However, there are risks associated with obstetric cholestasis and women with this should be monitored throughout their pregnancy. Liver blood tests are not always useful for assessing the risks to the baby but bile salt levels have been shown to be a predictor for higher risks to the baby. Bile salt levels are the best test to monitor the risks to the baby in women with obstetric cholestasis.

For your unborn baby

The baby is more likely to be born with "meconium stained amniotic fluid". This is where the baby has opened its bowels before delivery and this is often a sign that the baby has been distressed during the delivery.

The baby is more likely to be seen to have some changes on monitoring of their heartbeat during pregnancy and delivery. These changes are also thought to reflect signs of increased distress in the baby.

The baby is more likely to be born early (prematurely). Studies suggest that this occurs in between 3 in 10 and 4 in 10 pregnancies affected by obstetric cholestasis. Bile acids increase the uterus's sensitivity to oxytocin which is a hormone that stimulates the uterus to start contracting.

The baby is more likely to have respiratory distress after birth. Studies suggest that a baby born to a woman with obstetric cholestasis is 3 times more likely to have respiratory distress than a woman without obstetric cholestasis, even when the baby is born at the same age. This is more likely when the pregnant woman's bile acids are found to be high and it is important that babies born to these women are delivered at a hospital where there is a neonatal intensive care unit (NICU). Not all babies will need to be admitted to a NICU, even with respiratory distress, but it is more common.

There is a higher risk of a stillbirth. The risk of a stillbirth in a normal pregnancy is about 1 in 200 and it is a little higher in women with obstetric cholestasis. Again, this is more likely when the pregnant woman has high bile salts. These women will be encouraged to be induced to have their baby before 37 weeks of pregnancy as the majority of stillbirths will occur after this.

In women with bile acids between 19 and 39 micromil per litre (considered mild intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy) the risk of stillbirth is similar to the risks in women without ICP. However the risks may be increased for those with moderate intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy and is significantly increased for those with severe ICP (over 100 micromol per litre of bile acids).

For you

There are no ongoing problems affecting pregnant women with obstetric cholestasis although the itch can be very distressing.

How is obstetric cholestasis diagnosed?

Back to contentsThe diagnosis of obstetric cholestasis is suspected if, while pregnant, an itch develops without any skin rash to explain the itch. A blood test can detect the level of bile acids and liver enzymes in the blood, which will be higher than normal.

Other blood tests may be taken to measure other liver functions and to rule out other causes of liver problems such as viral hepatitis. In some cases the itch develops a week or more before the blood test becomes abnormal. Therefore, if the first blood test is normal then another may be done a week or so later if the itch continues.

If there is any suspicion that there might be another reason for the symptoms, an ultrasound scan of the liver and extra scans of the baby might be advised.

The diagnosis is confirmed where there is:

Itching that is not due to any other known cause (such as a skin disorder).

A high level of liver enzymes and/or bile salts in your blood that cannot be explained by any other liver disease.

After the diagnosis

Once diagnosed, blood tests will usually be performed every week or two until the baby is born. This is done to monitor the levels of liver enzymes and/or bile salts in your blood as evidence suggests that women with higher levels of bile salts are more likely to have complications from the obstetric cholestasis.

Both the itch and the high levels of liver enzymes and bile salts go away soon after the baby is born. A blood test is usually advised around 10 days after the baby is born to confirm that everything is back to normal.

What is the treatment for obstetric cholestasis?

Back to contentsUrsodeoxycholic acid may be used to treat obstetric cholestasis. This is used to lower the amount of bile acids in the blood. This has been shown to decrease the itching and also to decrease the risks of pre-term birth, distress of the baby during delivery, respiratory distress after birth and need for the baby to be admitted to a neonatal intensive care unit.

Sometimes a medication called rifampicin is used alongside ursodeoxycholic acid.

General measures to reduce the itch symptoms

Treatment with ursodeoxycholic acid may resolve the symptoms of itching.

However, some women have found that keeping cool helps to ease the itch. Tips to do this include:

Lowering the thermostat in the house.

Keeping uncovered at night.

Taking cool showers and baths.

Soaking feet or hands in iced water.

These measures may give some temporary relief, particularly before going to bed when the itch may ease enough to allow you to fall asleep. A bland moisturising cream may also give some temporary relief from itch. Some women find aqueous menthol cream helps.

Patient picks for Pregnancy complications

Pregnancy

Fetal anticonvulsant syndrome

Fetal anticonvulsant syndrome (FACS) - also known as fetal valproate syndrome and fetal hydantoin syndrome - is a group of malformations that can affect some babies if they are exposed to certain medicines known as antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) while in the womb. Most women with epilepsy will have a healthy child. Women with epilepsy who are pregnant and worried about their medication should not stop taking it without talking to their doctor. Stopping your medication makes you more likely to have seizures which can also be a risk to the baby.

by Dr Hayley Willacy, FRCGP

Pregnancy

Fetal alcohol syndrome

FAS is a pattern of disabilities that can develop in a baby as it grows in the womb (uterus) because the mother drank alcohol whilst pregnant and the baby is therefore exposed to alcohol before birth.

by Dr Toni Hazell, MRCGP

Further reading and references

- Pillarisetty LS, Sharma A; Pregnancy Intrahepatic Cholestasis. StatPearls Publishing; 2021.

- Itch in pregnancy; NICE CKS, November 2023 (UK access only)

- Sahni A, Jogdand SD; Effects of Intrahepatic Cholestasis on the Foetus During Pregnancy. Cureus. 2022 Oct 25;14(10):e30657. doi: 10.7759/cureus.30657. eCollection 2022 Oct.

- Pillarisetty LS, Sharma A; Pregnancy Intrahepatic Cholestasis.

- Intrahepatic Cholestasis of Pregnancy; RCOG

Continue reading below

Article history

The information on this page is written and peer reviewed by qualified clinicians.

Next review due: 19 Oct 2027

20 Oct 2024 | Latest version

Ask, share, connect.

Browse discussions, ask questions, and share experiences across hundreds of health topics.

Feeling unwell?

Assess your symptoms online for free

Sign up to the Patient newsletter

Your weekly dose of clear, trustworthy health advice - written to help you feel informed, confident and in control.

By subscribing you accept our Privacy Policy. You can unsubscribe at any time. We never sell your data.