Pemphigus

Peer reviewed by Dr Rosalyn Adleman, MRCGPLast updated by Dr Colin Tidy, MRCGPLast updated 13 Jun 2023

Meets Patient’s editorial guidelines

Medical Professionals

Professional Reference articles are designed for health professionals to use. They are written by UK doctors and based on research evidence, UK and European Guidelines. You may find one of our health articles more useful.

In this article:

Continue reading below

What is pemphigus?

Pemphigus describes a group of autoimmune disorders in which there is blistering of the skin and/or mucosal surfaces. The term used to include most bullous eruptions but improved diagnostic tests have allowed a reclassification of bullous diseases. The bullae are superficial and confined to the epidermal layer. This is in contrast to bullous pemphigoid where bullae are subepidermal.

Multiple subtypes of pemphigus disease have been identified based on their distinct clinical features and pathophysiology, including pemphigus vulgaris, pemphigus foliaceus, IgA pemphigus, and paraneoplastic pemphigus:1

Pemphigus vulgaris (PV) is the most common subset or variant and accounts for 70% of cases of pemphigus.

Pemphigus foliaceus (PF) is characterised by lesions which occur only in the skin and associated with antibodies to desmoglein 1 (DSG1).

Pemphigus herpetiformis, IgA pemphigus, paraneoplastic pemphigus and IgG/IgA pemphigus are rarer forms.2

Pathophysiology1

The particular autoimmune characteristic associated with pemphigus was first described in the 1960s. Essentially this is the identification of circulating IgG autoantibodies to antigens on the surface of keratinocytes.3

These pathogenic IgG autoantibodies bind to transmembrane desmosomal proteins of keratinocytes called desmogleins. The binding process results in loss of cell to cell adhesion, causing acantholysis and the production of superficial bullae in the epidermal layer. These superficial bullae rupture easily.4

An immunogenetic predisposition is now well established.5

The acantholysis occurs with or without complement activation. If complement is activated then this process may trigger release of inflammatory mediators and T-cell activation.

The cell surface desmogleins are principally DSG3, but 50-60% also have antibodies to DSG1.

The circulating IgG autoantibodies may be of both the IgG1 and IgG4 variety and disease activity correlates with the titre of antibodies.

Continue reading below

Pemphigus epidemiology1 6

Pemphigus vulgaris (PV) is by far the most common variant of pemphigus. Even this variant is rare. UK incidence has been claimed to be rising and is estimated to be 0.68 per 100,000 person years. Incidence is higher in women and in older age groups.7

The exact prevalence and incidence depends on the population studied reflecting the immunogenetics of pemphigus:

Pemphigus occurs worldwide but has a disproportionate geographic and ethnic distribution, with a significantly higher prevalence in patients of Ashkenazi Jewish or Mediterranean descent.

HLA-DRB1*0402 is associated with the disease in Ashkenazi Jews and DRB1*1401/04 and DQB1*0503 in non-Jewish patients of European or Asian descent.4

PV may occur at any age, but is most commonly seen between the ages of 30 and 70 years. In adolescents, girls are more often affected than boys.

The majority of affected children and adolescents have mucocutaneous disease.8

Pemphigus, like pemphigoid, appears to be triggered by environmental factors. Such factors include:

Removal of the trigger factor does not bring about resolution of the condition.

Pemphigus symptoms (presentation)1

General features

Skin lesions:4

Skin blisters are flaccid rather than tense. Intact blisters may not be found.

Lesions can extend easily and become large.

Blisters appear on normal or erythematous skin.

Affected skin is painful but very rarely pruritic (contrast with bullous pemphigoid).

Fluid in the blisters may be turbid.

Vegetating lesions (excess granulation and crusting) may be found in intertriginous areas.

Nail lesions may occur (paronychias, nail dystrophies and subungal haematomas).

Mucous membranes:

Bullae in the mouth are rarely intact.10

Lesions are usually irregular and poorly defined.

Lesions are painful and heal very slowly.

The oral cavity is most often affected (almost all patients). Gingival, buccal and palatine lesions occur.

Lesions may extend to cause hoarseness.

Eating and drinking may become very uncomfortable.

Other mucous membranes (conjunctivae, oesophagus and genitalia) may be involved.

Specific features

Pemphigus vulgaris (PV):

Most commonly presents with painful erosions or blisters on the oral mucosa, and these oral lesions may occur up to four months before skin lesions become evident.

Occasionally, the lesions will remain confined to the mouth.

A small number of patients will present with cutaneous blistering first; however, all will go on to develop oral lesions.

Pemphigus foliaceus (PF):

Presents with lesions on the skin only, and these patients will not go on to develop oral blisters.

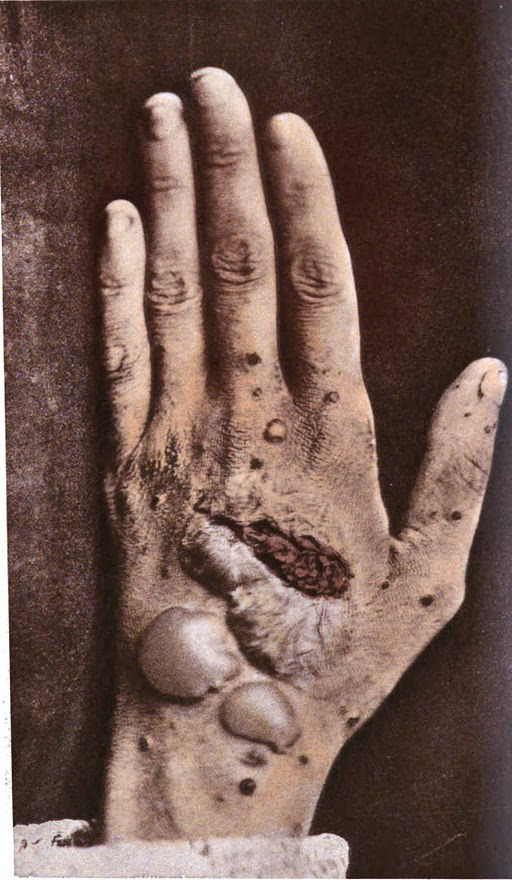

Pemphigus foliaceus

By George Henry Fox, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Paraneoplastic pemphigus (PNP):

It may present in patients who are already known to have an underlying neoplasm such as the B-cell lymphoproliferative disorders (eg, non-Hodgkin's lymphoma and chronic lymphocytic leukaemia).

It may present with mucocutaneous lesions before any underlying tumour has been diagnosed.

Patients present with painful ulcers on their mucous membranes, generalised polymorphic blistering and lichenoid skin lesions.

Continue reading below

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnoses will include other blistering eruptions of the skin and mucous membranes:

Aphthous ulcers (oral lesions).

Herpetic lesions.

Pemphigus herpetiformis.

Pemphigus erythematosus.

Lichen planus (bullous forms).

Pemphigus IgA.

Investigations

A person in whom a diagnosis of pemphigus is being considered should have the following investigations performed prior to being given any treatment.11

General tests

FBC and differential count.

U&Es.

LFTs.

Random blood glucose measurement.

Antinuclear antibody.

CXR.

Urinalysis for blood, protein and sugar.

Blood pressure measurement.

Bone densitometry.

Specific diagnostic tests

Differences of opinion are apparent amongst experts around the world on how best to diagnose and treat pemphigus vulgaris (PV):12

Skin biopsy should be from the edge of a blister and preferably examined fresh rather than in transport media (risk of false-negative results).

A skin or mucosal biopsy is sent for histological examination and immunofluorescence (direct and indirect).

Enzyme-linked immunosorbant assays (ELISAs) may be performed for DSG1 and DSG3 antibodies in serum.

Associated diseases

Pemphigus is associated with other autoimmune diseases. It has been reported in association with myasthenia gravis.

Pemphigus treatment and management1 13

There are differences of opinion on diagnosis and treatment, which require more research.14 General measures include advising patients with painful oral lesions to have soft diets and use soft toothbrushes. Topical analgesics or anaesthetics may give some symptomatic relief.

Treatment mainly relies on immune system suppression to prevent new lesion formation and heal existing bullous skin and/or mucous lesions. For all forms of pemphigus, corticosteroids are considered as a first-line therapy, with or without adjuvant therapies.

Generally, mild pemphigus treatment involves lower steroid doses compared to moderate/severe disease treatment, which involves higher steroid doses with the addition of steroid-sparing adjuvant agents.

Historically, azathioprine and mycophenolate mofetil were first-line corticosteroid-sparing adjuvant therapies. More recently, rituximab has become a treatment of choice, both at disease onset and especially for refractory disease.

Rituximab efficacy is higher when it is administered early in the course of the disease. Therefore, it should be considered as first-line treatment to improve efficacy and reduce cumulative doses of corticosteroids and their side effects.

Refractory pemphigus is difficult to treat, and there are many case studies supporting the use of various adjunct agents such as intravenous immune globulin (IVIg), immunoadsorption, or plasmapheresis, as well as other supportive treatments, including steroid mouthwashes and analgesic sprays to treat oral erosions.

For all forms, the most important factor is treating quickly and effectively and to taper corticosteroids to avoid recurrence.

Most treatments are considered successful if they improve disease significantly within the first two months, characterised by healed lesions without the appearance of new lesions.

If successful, treatment should be tapered gradually, starting with the corticosteroids, followed by the adjuvant nonsteroidal agent. Generally, clinically significant improvement is expected within weeks for PF and within months for PV.

Patients should be followed up routinely until all treatment has been stopped, and the patient remains in remission.

Complications

Secondary infection, particularly of skin lesions, may delay healing and increase scarring.

Malignancies from immunosuppression.

Growth impairment in children (corticosteroids and immunosuppressants).

Leukaemia and lymphomas (treatments causing prolonged immunosuppression).

Osteoporosis and adrenal insufficiency (from corticosteroids).

Prognosis

Untreated, the mortality associated with pemphigus vulgaris (PV) was 75%. The use of corticosteroids and adjuvant drugs has reduced the mortality rate significantly. It has been reported as 12% in the UK, with a 3 x higher risk of death compared with age-matched controls.7

Many experience serious side-effects from the drugs used, and many of the deaths occurring today are as a result of infection due to the immunosuppressive effects of the treatment. The outlook is worst in elderly patients and patients with extensive disease.

Further reading and references

- Kasperkiewicz M, Ellebrecht CT, Takahashi H, et al; Pemphigus. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2017 May 11;3:17026. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2017.26.

- Didona D, Paolino G, Di Zenzo G, et al; Pemphigus Vulgaris: Present and Future Therapeutic Strategies. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2022 Jan 1;12(1):e2022037. doi: 10.5826/dpc.1201a37. eCollection 2022 Feb.

- Didona D, Maglie R, Eming R, et al; Pemphigus: Current and Future Therapeutic Strategies. Front Immunol. 2019 Jun 25;10:1418. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.01418. eCollection 2019.

- Pemphigus vulgaris; DermNet.

- Pemphigus vulgaris and pemphigus vegetans; Primary Care Dermatology Society (PCDS).

- Malik AM, Tupchong S, Huang S, et al; An Updated Review of Pemphigus Diseases. Medicina (Kaunas). 2021 Oct 9;57(10):1080. doi: 10.3390/medicina57101080.

- Porro AM, Caetano Lde V, Maehara Lde S, et al; Non-classical forms of pemphigus: pemphigus herpetiformis, IgA pemphigus, paraneoplastic pemphigus and IgG/IgA pemphigus. An Bras Dermatol. 2014 Jan-Feb;89(1):96-106. doi: 10.1590/abd1806-4841.20142459.

- Tron F, Gilbert D, Joly P, et al; Immunogenetics of pemphigus: an update. Autoimmunity. 2006 Nov;39(7):531-9.

- Bystryn JC, Rudolph JL; Pemphigus. Lancet. 2005 Jul 2-8;366(9479):61-73.

- Tron F, Gilbert D, Mouquet H, et al; Genetic factors in pemphigus. J Autoimmun. 2005 Jun;24(4):319-28.

- Kridin K, Schmidt E; Epidemiology of Pemphigus. JID Innov. 2021 Feb 20;1(1):100004. doi: 10.1016/j.xjidi.2021.100004. eCollection 2021 Mar.

- Langan SM, Smeeth L, Hubbard R, et al; Bullous pemphigoid and pemphigus vulgaris - incidence and mortality in the UK: population based cohort study. BMJ. 2008 Jul 9;337:a180. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a180.

- Gurcan H, Mabrouk D, Razzaque Ahmed A; Management of pemphigus in pediatric patients. Minerva Pediatr. 2011 Aug;63(4):279-91.

- Brenner S, Wohl Y; A burning issue: burns and other triggers in pemphigus. Cutis. 2006 Mar;77(3):145-6.

- Santoro FA, Stoopler ET, Werth VP; Pemphigus. Dent Clin North Am. 2013 Oct;57(4):597-610. doi: 10.1016/j.cden.2013.06.002. Epub 2013 Aug 12.

- Harman KE, Albert S, Black MM; Guidelines for the management of pemphigus vulgaris. Br J Dermatol. 2003 Nov;149(5):926-37.

- Mimouni D, Nousari CH, Cummins DL, et al; Differences and similarities among expert opinions on the diagnosis and treatment of pemphigus vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003 Dec;49(6):1059-62.

- Di Lernia V, Casanova DM, Goldust M, et al; Pemphigus Vulgaris and Bullous Pemphigoid: Update on Diagnosis and Treatment. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2020 Jun 29;10(3):e2020050. doi: 10.5826/dpc.1003a50. eCollection 2020 Jul.

- Martin LK, Werth V, Villanueva E, et al; Interventions for pemphigus vulgaris and pemphigus foliaceus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009 Jan 21;(1):CD006263.

Article History

The information on this page is written and peer reviewed by qualified clinicians.

Next review due: 12 May 2028

13 Jun 2023 | Latest version

Feeling unwell?

Assess your symptoms online for free