Drug allergy

Peer reviewed by Dr Krishna Vakharia, MRCGPLast updated by Dr Colin Tidy, MRCGPLast updated 15 Dec 2022

Meets Patient’s editorial guidelines

- DownloadDownload

- Share

- Language

- Discussion

- Audio Version

Medical Professionals

Professional Reference articles are designed for health professionals to use. They are written by UK doctors and based on research evidence, UK and European Guidelines. You may find the Drug allergy article more useful, or one of our other health articles.

In this article:

Any drug can cause a skin reaction but some classes of drugs are characteristically associated with certain types of reaction.

Not all dermatological problems from drug allergies produce visible signs. The skin may appear normal with marked pruritus. It may be difficult to decide if the drug is really the cause of the problem and to withdraw it, especially if it is providing important treatment. Early withdrawal of the offending drug may limit its adverse effects.

Many of these reactions are immunological in origin. Possibly the drug acts as a hapten and binds to proteins to form a structure that the immune system recognises as 'not self'. Most immunologically mediated reactions can be allocated to one of the Gel and Coombs' classes of hypersensitivity:1 2

Type I

This is mediated by IgE and results in urticaria, angio-oedema and anaphylaxis. They are often caused by proteins and especially insulin.

Type II

This is a cytotoxic reaction which produces haemolysis and purpura. They are caused by penicillin, cephalosporins, sulfonamides and rifampin.

Type III

This is immune complex reactions, which result in vasculitis, serum sickness and urticaria. They can be caused by salicylates, chlorpromazine and sulfonamides. Drug-induced vasculitis is the most common form of vasculitis.3 Serum sickness is an immune-complex-mediated hypersensitivity reaction that classically presents with fever, rash, polyarthritis or polyarthralgias.

Type IV

This is delayed-type reactions with cell-mediated hypersensitivity, which result in contact dermatitis, exanthematous reactions and photoallergic reactions. These reactions are the most common and are usually caused by topical applications. Antibodies can be demonstrated in fewer than 5% of drug reactions, as the problem is cell-mediated. Type IV reactions are not dose-dependent. They usually begin one to three weeks after medication is started. This is significantly slower than most other reactions. There may be eosinophilia and they may recur if other drugs that are chemically related are used.

Continue reading below

How common are drug allergies? (Epidemiology)

Population studies suggest that drug allergies are over-diagnosed. A five-year analysis of confirmed drug-related eruptions, showed that 39.8% were caused by antibiotics, 21.2% by anti-inflammatories, 7.6% by contrast media and 31.4% by others (oral antidiabetics, antimycotics, antipsychotics, anti-epileptics and others).4

Notification of adverse drug reaction is on a voluntary basis through the Yellow Card Scheme in the British National Formulary.

Diagnosis

Back to contentsHistory and examination are as important here as in any field.5

When a patient develops a dermatological problem it is often difficult to decide which, if any, drugs are responsible.6

Take a careful history, avoiding being too ready to accept the patient's diagnosis of what is to blame, especially if they are on multiple medication. Take note of all medication, including prescribed, over-the-counter (OTC), 'alternative' and illicit drugs. It is not only prescription-only medications (POMs) that can cause trouble and patients may be surprised to learn that OTC products, 'natural therapies' and illegal drugs can also have adverse effects.

Urticaria may not be due to a drug at all but the ingestion of strawberries or shellfish. There may be a viral infection. Has the patient had that drug before? Were there any problems then?

Allergic patterns identified by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE)1

Immediate (developing within an hour) - anaphylaxis, urticaria, exacerbation of asthma (eg, by exposure to NSAIDs).

Non-immediate without systemic involvement (6-10 days after first drug exposure or within three days of second exposure) - widespread red macules or papules (exanthema‑like) or fixed drug eruption.

Non‑immediate reactions with systemic involvement (2-6 weeks after first drug exposure or within three days of second exposure) - drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) or drug hypersensitivity syndrome (DHS). The features are widespread red macules, papules or erythroderma, fever, lymphadenopathy, liver dysfunction and eosinophilia.

Toxic epidermolysis (7-14 days after first drug exposure or within three days of second exposure - see below.

Stevens-Johnson syndrome (7-14 days after first drug exposure or within three days of second exposure ) - see below.

Acute generalised exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP) (3-5 days after first drug exposure) - characterised by:widespread pustules, fever, neutrophilia.

Continue reading below

Associated drugs and rashes1

Back to contentsAcneform lesions

These are different from acne vulgaris in that they tend to be over the upper body rather than the face and there are no comedones.

Typical drugs are corticosteroids, halogens, haloperidol, hormones, isoniazid, lithium, phenytoin and trazodone:

The halogens are usually bromide or iodide.

The hormones may be anabolic steroids taken illicitly by bodybuilders or some athletes. Progestogens can also be a problem. This tends to be in low-oestrogen, high-progestogen oral contraceptive pills rather than progestogen-only pills or depot and implant contraceptives.

Acute generalised exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP)

This produces an acute onset of fever and generalised scarlatiniform erythema with many small, sterile, non-follicular pustules. It appears like pustular psoriasis.

Most cases are caused by antibiotics, often in the first few days of administration.

Some may be viral infections, mercury exposure, or UV radiation. They resolve spontaneously and rapidly, with fever and pustules lasting 7-10 days before desquamation over a few days.

Typical drugs include beta-lactam antibiotics, macrolides and less commonly, a wide variety of drugs including paracetamol, carbamazepine, tetracyclines, diltiazem, furosemide, hydrochlorothiazide, hydroxychloroquine, nifedipine, phenytoin, pseudoephedrine, sertraline, simvastatin, terbinafine and vancomycin.

Alopecia

Alopecia may occur with angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, allopurinol, anticoagulants, azathioprine, bromocriptine, beta-blockers, cyclophosphamide, hormones (especially those with androgenic effects), indinavir, NSAIDs, phenytoin, methotrexate, retinoids and valproate. It is usual with cyclophosphamide therapy but is quite rare with the other medications.

Bullous pemphigoid

Lesions like bullous pemphigoid may occur with penicillamine, captopril, chloroquine, ciprofloxacin, enalapril, furosemide, neuroleptics, penicillins, psoralen combined with ultraviolet A (PUVA) treatment, sulfasalazine and terbinafine

Erythema nodosum

With erythema nodosum, lesions most often occur with oral contraceptives but can occur with halogens, penicillin, sulfonamides and tetracyclines.

Erythroderma

Erythroderma is a diffuse redness of the skin. Offending drugs include allopurinol, anticonvulsants, captopril, chloroquine, chlorpromazine, cimetidine, diltiazem, lithium, nitrofurantoin, omeprazole, phenytoin, St John's wort and sulfonamides.

Fixed drug eruptions

These occur when lesions recur in the same area when the same drug is given.

Plaques are circular, violaceous and oedematous and they resolve with macular hyperpigmentation. The latent period is half an hour to eight hours after taking the drug. Perioral and periorbital lesions may occur but the hands, feet and genitalia are the usual sites to be involved.

Fixed drug eruptions are well recognised with many drugs, including anticonvulsants, aspirin and NSAIDs, benzodiazepines, cetirizine, ciprofloxacin, clarithromycin, doxycycline, fluconazole, hydroxyzine, lamotrigine, loratadine, metronidazole, oral contraceptives, penicillins, phenytoin, sulfonamides, tetracyclines and zolmitriptan.

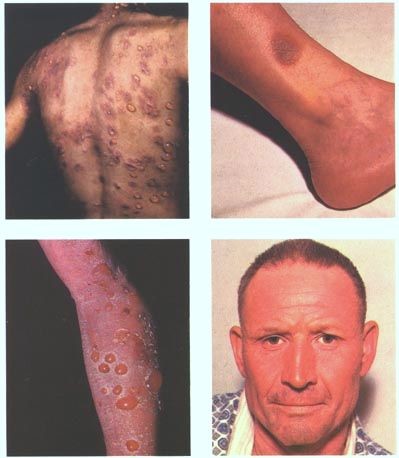

Drug Eruptions

© Jmarchn, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

By Jmarchn, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Hypersensitivity syndromes

True allergy may occur with allopurinol, amitriptyline, carbamazepine, lamotrigine, minocycline, NSAIDs, olanzapine, phenytoin, spironolactone and zidovudine.

Lichenoid reactions

Lesions are similar in appearance to lichen planus and there may be marked pruritus. They can accompany amlodipine, antimalarials, beta-blockers, captopril, diflunisal (now withdrawn), diltiazem, enalapril, furosemide, glimepiride, gold, leflunomide, penicillamine, phenothiazine, proton pump inhibitors, sildenafil, tetracycline, thiazides and ursodeoxycholic acid.

Lupus drug reactions

Unlike other drug reactions, lupus tends to require a long period of exposure.7 It produces symptoms like systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) but with skin findings being uncommon, or drug-induced subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (SCLE), which is characterised by annular psoriasiform, non-scarring lesions in a typical pattern for photosensitivity.

For SLE effects, hydralazine and minocycline are best known. For SCLE, hydrochlorothiazide is the most common.

Photosensitivity

The most common offenders are ACE inhibitors, amiodarone, amlodipine, celecoxib, chlorpromazine and other phenothiazines, diltiazem, furosemide, lovastatin, nifedipine, quinolones, sulfonamides, tetracyclines and thiazides.

Urticaria

The most likely drugs to cause urticaria are bupropion, carbamazepine, chlordiazepoxide, fluoxetine, imipramine, lamotrigine, lithium, paroxetine and trazodone.

Vasculitis

Vasculitis is most likely with fluoxetine, paroxetine and trazodone.

There are many other well-known reactions that are associated with drugs used in cancer chemotherapy and cytokine therapy. A list of such problems plus a more comprehensive list of other drug reactions may be found in the Medscape link under 'Further reading & references', below.

Potentially fatal drug allergies

Back to contentsMost drug eruptions are unpleasant rather than potentially life-threatening. There are two that are worthy of special mention.

Stevens-Johnson syndrome

See related separate article Stevens-Johnson syndrome.8 This is a much more serious drug eruption. It may be the result of malignancy in adults or viral infection in children but drugs should be considered as the potential culprit. It may be associated with allopurinol, anticonvulsants, aspirin and NSAIDS, carbamazepine, cimetidine, ciprofloxacin, codeine, diltiazem, erythromycin, furosemide, griseofulvin, indinavir, nitrogen mustard, penicillin, phenothiazines, phenytoin, ramipril, rifampicin, sulfonamides including co-trimoxazole and tetracyclines. Of these, sulfonamides are most often implicated.

Toxic epidermal necrolysis

See separate article Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis. Responsible agents include allopurinol, anticonvulsants, aspirin and NSAIDs, isoniazid, penicillins, phenytoin, prazosin, sulfonamides including co-trimoxazole, tetracyclines and vancomycin. Both Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis are often caused by infections, especially herpes simplex virus but, when caused by drugs, it is usually penicillins or sulfonamides.9

Clinical features are similar in all causes:

The reaction often starts with fever, sore throat, chills, headache, arthralgia, vomiting and diarrhoea and malaise.

Lesions may occur anywhere but most commonly affect the palms, soles, dorsum of hands and extensor surfaces. The rash may be confined to any one area of the body, most often the trunk. There is no pruritus.

Mouth involvement may be severe enough that patients may not be able to eat or drink.

Genitourinary involvement result in dysuria or an inability to pass urine.

The rash can begin as macules that develop into papules, vesicles, bullae, urticarial plaques, or confluent erythema.

The typical lesion has the appearance of a target, which is considered pathognomonic.

As stated above, toxic epidermal necrolysis is similar but more severe. Mucocutaneous detachment is more marked and a greater area is usually involved.

Both conditions require admission to hospital if not already there. The skin loss of toxic epidermal necrolysis is best managed in a burns unit.

Both but especially toxic epidermal necrolysis may result in scarring, severe sight impairment and even death.

Continue reading below

Investigations1

Back to contentsUsually no specific investigation is undertaken in primary care other than removing the suspected drug or even several drugs and monitoring for improvement.

Severe reactions require immediate investigation in secondary care (see 'Referral guidelines', below).

FBC may show leukopenia, thrombocytopenia and eosinophilia in patients with serious drug eruptions.

In the severe forms of reactions, LFTs and renal function should be monitored. In vasculitis, CXR and urinalysis are required.

Two blood samples should be taken for mast cell tryptase after a suspected drug‑related anaphylactic reaction.

In lupus-type responses, autoantibodies may be positive. Antihistone antibodies are often found in drug-induced SLE, whilst anti-Ro/SS-A antibodies are typical of drug-induced SCLE.10

Prick testing can be dangerous. It is usually reserved for penicillin/cephalosporin allergy where these drugs play an important role in patient management.11

Patch testing is often of little value but may be helpful where multiple drugs are suspected.12

Oral provocation tests may be regarded as the 'gold standard' but they have to be conducted under strict supervision.13

In chronic cases, biopsy may be helpful.

Associated diseases14

Back to contentsAlthough compromise of the immune system dampens the immune response, it may increase the risk of adverse reactions. One study of HIV-positive patients reported a serious adverse drug reaction incidence to antiretroviral therapy of 10%.15 Stevens-Johnson syndrome or toxic epidermolysis occurs in less than 0.5% of patients.

Common causes of non-immunological reactions

Not all drug reactions are immunological in origin.

The Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction classically occurs on starting penicillin for syphilis. It is due to the rapid destruction of spirochetes and the release of endotoxins from these organisms. It may occur if penicillin is given for another condition and it was not known that the patient had syphilis. If the reaction is to be anticipated, the diagnosis of syphilis having been made, it is usual to start steroids at a dose such as prednisolone 20 mg a day, a day before the first injection of penicillin and to tail off quite rapidly over the next few days. It is important to make the diagnosis and not to mistake it for allergy to penicillin and stop the antibiotic or syphilis will remain inadequately treated. This reaction may sometimes be seen with griseofulvin or ketoconazole given for dermatophyte infections and diethylcarbamazine treatment of onchocerciasis.

Photosensitivity is not an immunological reaction. It may be caused by production of free radicals or reactive oxygen species. There is an excessive sensitivity to sunburn. The phenothiazines and doxycycline are often involved.

Antimetabolites almost invariably cause certain adverse effects such as hair loss with cyclophosphamide.

Argyria is the accumulation of silver from silver nitrate nasal sprays. It causes blue-grey discoloration of skin and nails.

Aspirin and other NSAIDs can act on mast cells directly and cause release of histamine and other mediators without any immunological reaction. Other drugs that may do include X-ray contrast media, cimetidine, quinine, hydralazine, atropine, vancomycin, tubocurarine, opiates, cytokines and even alcohol.

Idiosyncratic reactions are unpredictable. In slow acetylators, drugs such as isoniazid may accumulate and cause peripheral neuropathy. If a patient with infectious mononucleosis is given ampicillin or amoxicillin there will almost invariably be a rash and the patient will probably be incorrectly labelled as allergic to penicillin. Penicillin V is the drug of choice for streptococcal sore throat and amoxicillin must not be given for throat infections, especially in young people.

Drug allergy treatment

Back to contentsIn uncomplicated cases, remove the offending drug and, if the condition resolves as expected, make notes to the effect that the patient has an adverse reaction to that drug. It may not be possible to be conclusive about which drug, if any, was responsible and, whilst caution is prudent, it is inappropriate to be too eager to label patients as allergic to any specific drug. Many people have probably been wrongly labelled as allergic to penicillin over the years and denied safe and effective treatment.

However, failure to note allergy can be fatal. Accurate record-keeping is very important to prevent a patient from being given a drug after an adverse reaction to it.

Provided that they are not thought to be part of the problem, antihistamines may give some symptomatic relief.

Some specific clinical scenarios1

Corticosteroids have been shown to be helpful for DRESS.16

Patients who have had a mild allergic reaction to NSAIDs may tolerate a selective COX-2 inhibitor.These should be started at the lowest possible dose.

Patients with asthma and nasal polyps have a high incidence of NSAID-related allergy.

Referral guidelines

Most drug reactions are minor and self-limiting but certain red flags must be noted and admission or specialist referral considered, including:

If the patient is systemically unwell.

If the rash is extensive, it could progress to a serious exfoliative dermatitis.

Detachment of the skin.

Involvement of mucous membranes including eyes and genitalia (may suggest Stevens-Johnson syndrome).

Patients should be referred to a specialist drug clinic if they have had:1

A suspected anaphylactic reaction.

A severe non-immediate cutaneous reaction (eg, drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, toxic epidermal necrolysis).

Prognosis

Back to contentsMost cases resolve without complications but it may take 10-14 days for the rash to disappear. Patients with exanthematous eruptions will have mild desquamation as the rash resolves.

The Stevens Johnson syndrome has a mortality of around 10% whilst toxic epidermal necrolysis carries a mortality of 50%.17

Further reading and references

- Seitz CS, Rose C, Kerstan A, et al; Drug-induced exanthems: correlation of allergy testing with histologic diagnosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013 Nov;69(5):721-8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2013.06.022. Epub 2013 Aug 6.

- Couto M, Silva D, Ferreira A, et al; Intradermal Tests for Diagnosis of Drug Allergy are not Affected by a Topical Anesthetic Patch. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2014 Sep;6(5):458-62. doi: 10.4168/aair.2014.6.5.458. Epub 2014 Jun 18.

- Management of allergy to penicillins and other beta-lactams; British Society for Allergy and Clinical Immunology (BSACI) (2015)

- Chiriac AM, Banerji A, Gruchalla RS, et al; Controversies in Drug Allergy: Drug Allergy Pathways. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2019 Jan;7(1):46-60.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2018.07.037. Epub 2018 Dec 17.

- Phillips EJ, Bigliardi P, Bircher AJ, et al; Controversies in drug allergy: Testing for delayed reactions. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2019 Jan;143(1):66-73. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2018.10.030. Epub 2018 Dec 17.

- Drug allergy: diagnosis and management of drug allergy in adults children and young people; NICE Clinical guideline (September 2014; updated November 2018).

- Beatty R; Hypersensitivity

- Radic M, Martinovic Kaliterna D, Radic J; Drug-induced vasculitis: a clinical and pathological review. Neth J Med. 2012 Jan;70(1):12-7.

- Heinzerling LM, Tomsitz D, Anliker MD; Is drug allergy less prevalent than previously assumed? A 5-year analysis. Br J Dermatol. 2012 Jan;166(1):107-14. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2011.10623.x.

- Akpinar F, Dervis E; Drug Eruptions: An 8-year Study Including 106 Inpatients at a Dermatology Clinic in Turkey. Indian J Dermatol. 2012 May;57(3):194-8. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.96191.

- Knowles SR, Shear NH; Recognition and management of severe cutaneous drug reactions. Dermatol Clin. 2007 Apr;25(2):245-53, viii.

- Rubin RL; Drug-induced lupus.; Toxicology. 2005 Apr 15;209(2):135-47.

- Mockenhaupt M; Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis: clinical patterns, diagnostic considerations, etiology, and therapeutic management. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2014 Mar;33(1):10-6.

- Harr T, French LE; Toxic epidermal necrolysis and Stevens-Johnson syndrome. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2010 Dec 16;5:39.

- Marzano AV, Tavecchio S, Menicanti C, et al; Drug-induced lupus erythematosus. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2014 Jun;149(3):301-9.

- Frew A; General principles of investigating and managing drug allergy. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2011 May;71(5):642-6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2011.03933.x.

- Liippo J, Pummi K, Hohenthal U, et al; Patch testing and sensitization to multiple drugs. Contact Dermatitis. 2013 Nov;69(5):296-302. doi: 10.1111/cod.12076.

- Rerkpattanapipat T, Chiriac AM, Demoly P; Drug provocation tests in hypersensitivity drug reactions. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011 Aug;11(4):299-304. doi: 10.1097/ACI.0b013e328348a4e9.

- Chaponda M, Pirmohamed M; Hypersensitivity reactions to HIV therapy. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2011 May;71(5):659-71. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2010.03784.x.

- Eluwa GI, Badru T, Agu KA, et al; Adverse drug reactions to antiretroviral therapy (ARVs): incidence, type and risk factors in Nigeria. BMC Clin Pharmacol. 2012 Feb 27;12:7. doi: 10.1186/1472-6904-12-7.

- Oelze LL, Pillow MT; Phenytoin-induced drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) syndrome: a case report from the emergency department. J Emerg Med. 2013 Jan;44(1):75-8. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2011.05.052.

- Mockenhaupt M; The current understanding of Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2011 Nov;7(6):803-13; quiz 814-5.

Continue reading below

Article history

The information on this page is written and peer reviewed by qualified clinicians.

Next review due: 14 Nov 2027

15 Dec 2022 | Latest version

Ask, share, connect.

Browse discussions, ask questions, and share experiences across hundreds of health topics.

Feeling unwell?

Assess your symptoms online for free