Acute otitis media in children

Peer reviewed by Dr Colin Tidy, MRCGPLast updated by Dr Hayley Willacy, FRCGP Last updated 27 Sept 2023

Meets Patient’s editorial guidelines

- DownloadDownload

- Share

- Language

- Discussion

- Audio Version

Medical Professionals

Professional Reference articles are designed for health professionals to use. They are written by UK doctors and based on research evidence, UK and European Guidelines. You may find the Middle ear infection (otitis media) article more useful, or one of our other health articles.

In this article:

Continue reading below

What is otitis media?

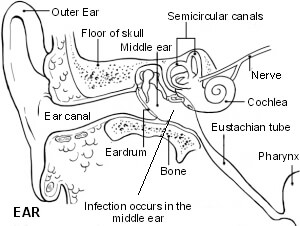

Otitis media (OM) also known as an ear infection is a very common problem in general practice. It describes two conditions which form part of a continuum of disease: acute otitis media (AOM) and otitis media with effusion (OME). Both occur mainly in childhood and both may be caused by bacterial or viral infection.

Spectrum of otitis media1

Back to contentsOtitis media (OM) is an umbrella term for a group of complex infective and inflammatory conditions affecting the middle ear. All OM involves pathology of the middle ear and middle ear mucosa. OM is a leading cause of healthcare visits worldwide and its complications are important causes of preventable hearing loss, particularly in the developing world.2 3

There are various subtypes of OM. These include acute otitis media, otitis media with effusion (OME), chronic suppurative otitis media (CSOM), mastoiditis and cholesteatoma. They are generally described as discrete diseases but in reality there is a great degree of overlap between the different types. OM can be seen as a continuum/spectrum of diseases.

Acute otitis media is acute inflammation of the middle ear and may be caused by bacteria or viruses. A subtype of AOM is acute suppurative OM, characterised by the presence of pus in the middle ear. In around 5% the eardrum perforates.

OME is a chronic inflammatory condition without acute inflammation, which often follows a slowly resolving AOM. There is an effusion of glue-like fluid behind an intact tympanic membrane in the absence of signs and symptoms of acute inflammation.

CSOM is long-standing suppurative middle ear inflammation, usually with a persistently perforated tympanic membrane.

Mastoiditis is acute inflammation of the mastoid periosteum and air cells occurring when AOM infection spreads out from the middle ear.

Cholesteatoma occurs when keratinising squamous epithelium (skin) is present in the middle ear as a result of tympanic membrane retraction.

Most children with acute otitis media experience a self-limiting illness and many will not present to a doctor. A few will have recurrent or chronic problems and may require referral.

Otitis media

Continue reading below

Pathophysiology4

Back to contentsInfecting organisms reach the middle ear from the nasopharynx. Children are particularly vulnerable to the transfer of organisms from the nasopharynx to the ear. As children grow bigger, the angle between the Eustachian tube and the wall of the pharynx becomes more acute, so that coughing or sneezing tends to push it shut. In small children, the less acute angle facilitates infected material being transmitted through the tube to the middle ear. Better Eustachian tube function (in terms of active muscle opening) has been found in some studies to be protective.5 6

In most cases, acute otitis media can be regarded as a complication of a preceding or concomitant upper respiratory infection.7

The most common bacterial pathogens are Haemophilus influenzae, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Moraxella catarrhalis and Streptococcus pyogenes.

Culture of fluid obtained from the middle ear reveals pathogenic bacteria in up to 70% of cases. S. pneumoniae and H. influenzae together comprise 60-80% of these.

Since the introduction of the pneumococcal vaccine the most common pathogen may be changing from S. pneumoniae to H. influenzae.

Bacterial pathogens cannot be isolated from middle ear fluid in around 30% of AOM cases.7

The most common viral pathogens are respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) and rhinovirus.

The COVID-19 virus (SARS-CoV-2) has been isolated from the middle ears of deceased patients, although some did not have previous clinical evidence of acute otitis media.8

Otitis media epidemiology

Back to contentsAt least 70% of children will experience one or more attacks of acute otitis media by the age of 2 years and about half experience more than three episodes:9

The peak age of incidence is 6-15 months and decreases with age. It is less common at school age.

More than 75% of episodes occur in children under 10 years of age.

Otitis media occurs more in the winter than the summer months, as it is usually associated with a cold.10

Otitis media occurs very slightly more frequently in boys than in girls.

AOM is a particular issue in the developing world. A 2012 literature review suggested that the annual global incidence of AOM is around 10% - over 700 million cases per year and about half in under-5s.11

Incidence varies by a factor of more than ten between high-income and low-income countries. Of these, chronic suppurative otitis media develops in around 5%.11

The authors estimate that 33 per 10 million die of complications of OM, most of them babies under 12 months of age in developing countries.11

Continue reading below

Otitis media risk factors4

Back to contentsRisk factors include:

Younger age.

Male sex.

Smoking in the household.

Immune deficiency.

Daycare/nursery attendance.

Formula feeding - breast-feeding for three months and above has a protective effect.

Craniofacial abnormalities - eg, Down's syndrome, cleft palate.

Ciliary dysfunction.

Cochlear implant.

Additionally, recurrent acute otitis media is associated with:

Early first episode.

Dummy use.

Winter season.

Supine feeding.

Otitis media symptoms (presentation)9

Back to contentsOtitis media symptoms

Acute otitis media commonly presents with acute onset of symptoms:

Pain (younger children may pull at the ear).

Malaise.

Irritability, crying, poor feeding, restlessness.

Fever.

Coryza/rhinorrhoea.

Vomiting.

Signs

Examination may reveal:

High temperature (febrile convulsions may be associated with the temperature rise in AOM).

A red, yellow or cloudy tympanic membrane.

Bulging of the tympanic membrane.

An air-fluid level behind the tympanic membrane.

Discharge in the auditory canal secondary to perforation of the tympanic membrane - this may obscure the view completely.

The pinna may be red.

Children under 6 months of age may display nonspecific symptoms. They may also have co-existing disease such as bronchiolitis, and the tympanic membrane may be difficult to see: it often lies in an oblique position and the ear canal tends to collapse closed.

Perforation of the eardrum often relieves pain. A child who is screaming and distressed may settle remarkably quickly - and then the ear starts to discharge green pus.

Differential diagnosis12

Back to contentsThe list of differential diagnoses is quite long; however, careful history taking and examination should distinguish between them clearly.

OME - fluid in the middle ear without inflammation.

Respiratory tract infection alone (there may be slight reddening of the tympanic membrane).

Referred pain (especially from teeth).

Herpetic infection of the ear.

Trauma.

Chronic suppurative otitis media (persistent inflammation and discharge through a perforated tympanic membrane for more than two weeks).

Bullous myringitis (rare - caused by mycoplasma pneumonia causing bullous red blisters on the tympanic membrane. It usually settles in a few days).

Often children who are unwell have a slightly red eardrum but in AOM it is very red.

Investigations12

Back to contentsUsually no investigation is required.

Culture of discharge from an ear may be indicated in chronic or recurrent perforation or if grommets are present.

Audiometry should be performed if chronic hearing loss is suspected; however, not during acute infection.

CT or MRI may be appropriate if complications are suspected.

Acute Otitis treatment and management

Back to contentsNICE guidance on antimicrobial prescribing for otitis media13

This recommends that children who are systemically very unwell, have symptoms and signs of a more serious illness, or are at higher risk of complications should be offered an immediate antibiotic prescription and advice. Children and young people should be referred to hospital if they have acute otitis media associated with a severe systemic infection, or have acute complications including mastoiditis, meningitis, intracranial abscess, sinus thrombosis or facial nerve paralysis.

The majority of cases of AOM will resolve spontaneously. Without specific treatment symptoms improve within 24 hours in 60% of children and settle within three days in 80% of children. Whilst adequate analgesia should be prescribed in all cases, antibiotics should be avoided in mild-to-moderate cases and when there is diagnostic uncertainty in patients aged 2 years and under.14

If an antibiotic is not required13

Consider eardrops containing an anaesthetic and an analgesic for pain if:

An immediate oral antibiotic prescription is not given; and

There is no eardrum perforation or otorrhoea.

Review treatment if symptoms do not improve within seven days or they worsen at any time.

If an antibiotic is required

Prescribe a five-day course of amoxicillin.

For children who are allergic to penicillin, prescribe a five-day course of erythromycin or clarithromycin.

If a second-choice antibiotic is needed for children with worsening symptoms who have taken one of the above preparations for at least 2 to 3 days, a 5- to 7-day course of co-amoxiclav should be offered.

Other treatments

Antihistamines, decongestants and echinacea are of no benefit.15

A warm compress over the affected ear may help reduce the pain.

If an episode of AOM fails to improve or worsens

Reassess and re-examine

Admit for immediate paediatric assessment, children younger than 3 months of age with a temperature of 38°C or more.

Admit for immediate assessment, children with suspected acute complications of AOM (eg, meningitis, mastoiditis).

Consider admitting children who are systemically very unwell, and children 3-6 months of age with a temperature of 39°C or more.

Exclude other causes of middle ear inflammation.

If symptoms persist despite two courses of antibiotics, seek specialist advice from an ENT specialist.

Treatment of recurrent AOM

Consider referral to an ENT specialist especially if:

The child has a craniofacial abnormality.

Recurrent episodes are very distressing or associated with complications.

Children with discharge or perforation have symptoms which have not resolved within three weeks

Children have had recurrent AOM (more than three episodes in six months or more than four in one year).

Children have impaired hearing following AOM. If aged under 3 with OME, bilateral effusions and mild hearing loss with no speech, language or developmental problems, observe initially. Otherwise, refer for consideration of grommets.

Children are over the age of 3 and have gone on to develop OME or have language or behavioural problems. They may benefit from surgical intervention such as the insertion of grommets and should be referred for a specialist opinion.16

If referral is not necessary:

Manage acute episodes in the same way as for initial presentation.

In people with grommets who present with acute discharge:

Consider taking an ear swab for culture and sensitivity.

Treat as for initial presentation or seek advice from an ENT specialist.

Do not start long-term prophylactic antibiotics in primary care.

Complications4

Back to contentsMost cases of AOM will resolve spontaneously with no sequelae.

Perforation of the eardrum is fairly common: progression to chronic suppurative otitis media may occur.

Labyrinthitis, meningitis, intracranial sepsis or facial nerve palsy are very rare and occur in fewer than 1 in 1,000.

Recurrent episodes may lead to scarring of the eardrum with permanent hearing impairment, chronic perforation and otorrhoea, cholesteatoma or mastoiditis.

In a small child with a high temperature there is a risk of febrile convulsions. This is discussed more fully in its own article.

Rare complications include:

Petrositis.

Acute necrotic otitis,

Otitic hydrocephalus (hydrocephalus associated with AOM, usually accompanied by lateral sinus thrombosis but the exact pathophysiology is unclear).

Subarachnoid abscess.

Subdural abscess.

Sigmoid sinus thrombosis.

Rarely, systemic complications can occur, including:

Bacteraemia.

Prognosis12

Back to contentsWith the exception of the few complications given above, there is usually complete resolution in a few days. Symptoms resolve in 24 hours in 60% of children.

Prevention17

Back to contentsIn recurrent otitis media (either three or more acute infections of the middle ear cleft in a six-month period, or at least four episodes in a year) strategies for managing the condition include the assessment and modification of risk factors where possible, repeated courses of antibiotics for each new infection and antibiotic prophylaxis. The latter should not be started without specialist advice (due to concerns over antibiotic resistance).

Advise adult patients and parents of child patients on avoiding exposure to passive smoking. In the case of small children advise against use of dummies and against flat, supine feeding. Ensure that children have had a complete course of pneumococcal vaccinations as part of the routine childhood immunisation schedule, although this only reduces risk of infection by 5%.

Limited evidence suggests that insertion of grommets results in fewer episodes of AOM in the first six months. Prevailing advice is to refer for this option if this is requested by the parents.

Dr Mary Lowth is an author or the original author of this leaflet.

Further reading and references

- National Deaf Children's Society

- Marchisio P, Galli L, Bortone B, et al; Updated Guidelines for the Management of Acute Otitis Media in Children by the Italian Society of Pediatrics: Treatment. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2019 Dec;38(12S Suppl):S10-S21. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000002452.

- Qureishi A, Lee Y, Belfield K, Birchall JP, Daniel M; Update on otitis media – prevention and treatment. Infection and Drug Resistance. 2014;7:15-24. doi:10.2147/IDR.S39637.

- Tesfa T, Mitiku H, Sisay M, et al; Bacterial otitis media in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Infect Dis. 2020 Mar 17;20(1):225. doi: 10.1186/s12879-020-4950-y.

- Nash K, Macniven R, Clague L, et al; Ear and hearing care programs for First Nations children: a scoping review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2023 Apr 19;23(1):380. doi: 10.1186/s12913-023-09338-2.

- Danishyar A, Ashurst JV; Acute Otitis Media

- Dinc AE, Damar M, Ugur MB, et al; Do the angle and length of the eustachian tube influence the development of chronic otitis media? Laryngoscope. 2015 Sep;125(9):2187-92. doi: 10.1002/lary.25231. Epub 2015 Mar 16.

- Swarts JD, Casselbrant ML, Teixeira MS, et al; Eustachian tube function in young children without a history of otitis media evaluated using a pressure chamber protocol. Acta Otolaryngol. 2014 Jun;134(6):579-87. doi: 10.3109/00016489.2014.882017.

- Heikkinen T, Chonmaitree T; Importance of respiratory viruses in acute otitis media. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2003 Apr;16(2):230-41.

- Jeican II, Aluas M, Lazar M, et al; Evidence of SARS-CoV-2 Virus in the Middle Ear of Deceased COVID-19 Patients. Diagnostics (Basel). 2021 Aug 25;11(9). pii: diagnostics11091535. doi: 10.3390/diagnostics11091535.

- Jamal A, Alsabea A, Tarakmeh M, et al; Etiology, Diagnosis, Complications, and Management of Acute Otitis Media in Children. Cureus. 2022 Aug 15;14(8):e28019. doi: 10.7759/cureus.28019. eCollection 2022 Aug.

- Zemek R, Szyszkowicz M, Rowe BH; Air pollution and emergency department visits for otitis media: a case-crossover study in Edmonton, Canada. Environ Health Perspect. 2010 Nov;118(11):1631-6.

- Monasta L, Ronfani L, Marchetti F, Montico M, Vecchi Brumatti L, Bavcar A, et al; (2012) Burden of Disease Caused by Otitis Media: Systematic Review and Global Estimates. PLoS ONE 7(4): e36226. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0036226.

- Otitis media - acute; NICE CKS, July 2023 (UK access only)

- Otitis media (acute): antimicrobial prescribing; NICE Guideline (2018, updated March 2022)

- Toll EC, Nunez DA; Diagnosis and treatment of acute otitis media: review. J Laryngol Otol. 2012 Oct;126(10):976-83. Epub 2012 Jul 19.

- Cherpillod J; Acute otitis media in children. Int J Gen Med. 2011;4:421-3. Epub 2011 Jun 2.

- Surgical management of children with otitis media with effusion (OME); NICE Clinical Guideline (February 2008)

- Gaddey HL, Wright MT, Nelson TN; Otitis Media: Rapid Evidence Review. Am Fam Physician. 2019 Sep 15;100(6):350-356.

Continue reading below

Article history

The information on this page is written and peer reviewed by qualified clinicians.

Next review due: 25 Sept 2028

27 Sept 2023 | Latest version

Ask, share, connect.

Browse discussions, ask questions, and share experiences across hundreds of health topics.

Feeling unwell?

Assess your symptoms online for free