Cardiac catheterisation

Peer reviewed by Dr Krishna Vakharia, MRCGPLast updated by Dr Colin Tidy, MRCGPLast updated 22 Nov 2022

Meets Patient’s editorial guidelines

- DownloadDownload

- Share

- Language

- Discussion

- Audio Version

Cardiac catheterisation is a way to find out detailed information about your heart and coronary arteries and it is also possible to provide treatment for some conditions at the same time.

In this article:

Video picks for Heart tests

Continue reading below

What is a cardiac catheterisation?

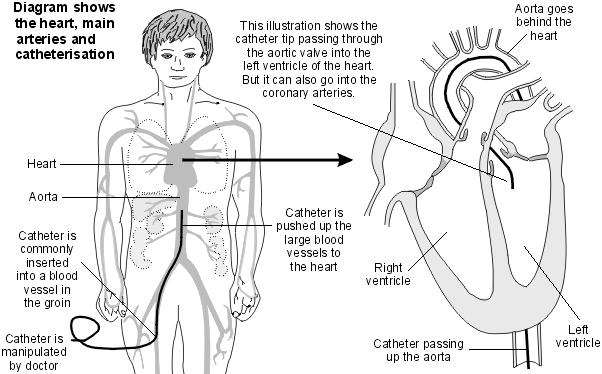

Cardiac catheterisation is a procedure in which a very thin plastic catheter is passed into the chambers of the heart. The catheter can also be passed into the main blood vessels of the heart (the coronary arteries).

How is cardiac catheterisation done?

Back to contentsCardiac catheterisation

You lie flat on a couch in a catheterisation room. An X-ray machine is mounted above the couch. A catheter is inserted through a wide needle or small cut in the skin into a blood vessel in the groin area or arm. It is carried out under local anaesthetic which is injected into the skin above the blood vessel. Therefore, it should not hurt when the catheter is passed into the blood vessel.

The doctor gently pushes the catheter up the blood vessel towards the heart. Low-dose X-rays are used to monitor the progress of the catheter tip which is gently manipulated into the heart chambers (ventricles and atria) and/or coronary arteries. You may be able to see the progress of the catheter on the X-ray monitor.

You cannot feel the catheter in the blood vessels or heart. You may feel an occasional 'missed' or 'extra' heartbeat during the procedure. This is normal and of little concern. During the procedure your heartbeat is monitored by electrodes placed on your chest which provide a heart tracing (electrocardiogram, or ECG). Sometimes a sedative is given before the test if you are anxious.

When the test is over, the catheter is gently pulled out. If it was inserted through a small cut in the skin in the arm then you will normally need a few stitches. If it was inserted through a wide needle in your groin then they will apply pressure over the site of insertion for about 10 minutes to prevent any bleeding.

Continue reading below

What is cardiac catheterisation used for?

Back to contentsCoronary angiography

This is the most common test using the cardiac catheter. This procedure shows up the structure of the coronary arteries 'like a road map'. It aims to detect any narrowing of the coronary arteries and the exact site and severity of any narrowing.

The coronary arteries are the blood vessels that take blood to the heart muscle. If they become narrowed then less blood and oxygen get to the heart muscle (coronary artery disease). This can cause chest pain (angina), heart failure and other heart conditions. Therefore, you may have this test to help to diagnose and assess these heart problems.

The tip of the catheter is pushed just inside a main coronary artery. Some dye is then injected down the catheter into the artery. X-ray films are taken as the dye is injected (the dye shows up clearly on X-ray films). The X-ray films are recorded as a moving picture and this is called an angiogram. The angiogram shows the vessels filling with blood and the sites of any narrowing can be seen. See the separate leaflet called Coronary Angiography.

Other uses

A cardiac catheter can be used for various other functions which include:

Measuring the pressure within the heart chambers. The tip of the catheter can include a tiny pressure monitor. For example, the pressure either side of a heart valve can be measured by placing the catheter tip in different positions within the heart chambers. This can help to determine how well the valve is opening.

To find how well the ventricles of the heart contract. Dye can be injected into the heart chambers and an X-ray video of the heart can see the dye as the heart chambers are pumping.

To sample blood from within the heart chambers or coronary arteries. For example, to determine how much oxygen is in blood in certain parts of the heart.

To perform 'procedures' within the heart or coronary arteries - for example:

The catheter tip can include a tiny balloon which can inflate to widen narrowed heart valves (valvuloplasty) or narrowed coronary arteries (angioplasty). Alternatively, a small cylindrical tube (stent) can be placed across a narrowing. See the separate leaflet called Coronary Angioplasty.

Destruction treatment (catheter ablation). In this procedure, a device at the catheter tip can destroy a tiny section of heart tissue. This is sometimes used to treat abnormal heart rhythms (arrhythmias). The source or 'trigger' of the abnormal electrical impulses can sometimes be destroyed by this technique. This is only suitable if the exact site of the trigger can be found by special tests and be located accurately by the catheter tip.

Newer techniques are being developed which use devices at the tip of the catheter. For example, a tiny ultrasound scanner at the tip of the catheter is a recent development. This can give detailed pictures from within coronary arteries.

Cardiac catheterisation tests in children

Cardiac catheterisation is commonly done to assess the heart of children and babies with certain types of congenital heart disease. A 'congenital' condition is one that is present from birth. A general anaesthetic is normally given to children to keep them asleep during the procedure.

How do I prepare for a cardiac catheterisation?

Back to contentsYou should receive instructions from your local hospital about what you need to do. The sort of instructions may include:

If you take warfarin or another 'blood-thinning' medicine (anticoagulant) you will need to stop this for 2-3 days before the test. (This prevents excessive bleeding in the area where the catheter is inserted.)

If you take insulin or medicines for diabetes, you may need to alter the timing of when you take these. Some medicines may need to be stopped for 48 hours. Your doctor should clarify this with you.

If you may be pregnant, you need to tell the doctor who will do the test.

You may be asked to not eat or drink for a few hours before the test.

You may be asked to shave both groins before the test.

You will have to sign a consent form at some point before the test. This is to confirm that you understand the procedure, understand the possible complications (see below) and agree to the procedure being done.

Continue reading below

How long does cardiac catheterisation take?

Back to contents'Routine' cardiac catheterisation for angiography usually takes about 20-30 minutes. In most cases it is done as a day-case procedure. However, some procedures using a cardiac catheter can take longer and some people need to stay in hospital for a short time.

After the test

Back to contentsThe doctor will discuss what he or she found during the test. A letter is also sent to your GP giving details of the test results.

You will need to rest for a few hours after the test. You should ask a friend or relative to accompany you home. Most people are able to resume their normal activities the next day.

There may be some bruising at the site of the catheter insertion, which may be a little sore when the anaesthetic wears off. Painkillers such as paracetamol will help to ease this.

You may need to have some stitches removed after about seven days if a small cut was made to insert the catheter.

Are there any risks or side-effects?

Back to contentsMost of the side-effects are minor and may include:

A bruise which may form under the skin where the catheter was inserted. This is not serious but it may be sore for a few days.

The small wound where the catheter is inserted sometimes becoming infected. Tell your GP if the wound becomes red and tender. A short course of antibiotics will usually deal with this if it occurs.

If dye is used to obtain X-ray pictures (angiogram), you may have a hot, flushing feeling when the dye is injected. Many people also describe a warm feeling in the groin when the dye is injected - as if they have 'wet themselves'. These feelings last just a few seconds (and the operator will tell you when they are about to inject the dye). Rarely, some people have an allergic reaction to the dye.

Serious complications are very rare. For example, some people have had a stroke (caused by a blood clot going to the brain) or a heart attack (myocardial infarction) during the procedure. Also, rarely, the catheter may damage a coronary artery.

The risk of serious complications is small and is mainly in people who already have serious heart disease. As a consequence of serious complications, a few people have died during this procedure. Your doctor will only recommend cardiac catheterisation if they feel the benefits outweigh the small amount of risk.

Patient picks for Heart tests

Tests and investigations

Ambulatory electrocardiogram

Ambulatory electrocardiogram monitors your heart when you are doing your normal activities. It helps to detect abnormal heart rates and rhythms (arrhythmias). The arrangements, and the way tests are performed, may vary between different hospitals. Always follow the instructions given by your doctor or local hospital.

by Dr Toni Hazell, MRCGP

Tests and investigations

Exercise Tolerance Testing

An exercise tolerance test (ETT) records the electrical activity of the heart whilst exercising. It is most useful in patients who experience chest pain on exertion. It is also used to detect whether heart rhythm abnormalities can be brought on by exercise.

by Dr Philippa Vincent, MRCGP

Further reading and references

- O'Gallagher K, Dancy L, Pearce L, et al; Interpretation of cardiac catheterisation reports: a guide for primary care. Br J Gen Pract. 2017 Oct;67(663):481-482. doi: 10.3399/bjgp17X693053.

- Manda YR, Baradhi KM; Cardiac Catheterization Risks and Complications. StatPearls, June 2022.

- cardiovascular conditions; National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE).

Continue reading below

Article history

The information on this page is written and peer reviewed by qualified clinicians.

Next review due: 21 Nov 2027

22 Nov 2022 | Latest version

Ask, share, connect.

Browse discussions, ask questions, and share experiences across hundreds of health topics.

Feeling unwell?

Assess your symptoms online for free

Sign up to the Patient newsletter

Your weekly dose of clear, trustworthy health advice - written to help you feel informed, confident and in control.

By subscribing you accept our Privacy Policy. You can unsubscribe at any time. We never sell your data.