Movember spotlight: black men's mental health

Peer reviewed by Dr Krishna Vakharia, MRCGPAuthored by Amberley DavisOriginally published 2 Nov 2023

Meets Patient’s editorial guidelines

- DownloadDownload

- Share

- Language

- Discussion

Black men are more likely to experience poor mental health than any other ethnic group, yet they are the least likely to receive treatment. This Movember, we explore this contradiction and ask what can be done to get boys and men the support they need.

In this article:

Continue reading below

Stigma, barriers, and discrimination

Male depression has been labelled a mental health crisis, with men accounting for around 80% of suicides worldwide1.

For black men, and particularly young black men, this gender gap and the male stigma around mental health is compounded by cultural barriers and experiences of racism. This has made black men the most likely group to develop mental health problems2.

UK statistics:3

3.2% of black men experience symptoms of psychosis, compared to 1.3% of Asian men and 0.3% of white men. There is no significant variation by ethnic group among women.

23% of people from UK black communities are experiencing a common mental health problem in any given week. This is compared to 18% of those from Asian communities and 17% from white communities.

6% of black people are treated for mental health problems, compared to 13% of white people. This is the lowest treatment rate of any ethnic group.

There are lots of complex reasons for this, and every person's circumstances are unique. But there are some overarching factors that help explain how both race and gender inequalities and barriers have led to this crisis. We explore these factors, with help from mental health expert and counsellor Matthew Schubert.

Intergenerational trauma

Back to contentsThe concept of intergenerational trauma may help explain some of the mental health challenges faced by black men. This is the idea that you can feel the effects of trauma experienced by your family members in previous generations4, as Schubert explains:

"Much like the inheritance of genes, life experiences are transmitted across generations. When trauma, oppression, and socio-economic adversities affect a parent or grandparent, their impact often carries forward through their children."

Black communities have experienced more trauma than other racial groups, due to a long history of racism and discrimination4. Children learn how to respond to their surroundings in a similar way as their parents responded to theirs. Consequently, it's thought that the burden of inherited trauma explains why more black people experience post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) than other ethnicities5.

Fatherless household epidemic

But are there intergenerational traumas that might affect black men in particular? Schubert believes so: "the fatherless household epidemic is more common in the black communities. When boys don't have a father figure in the home to model the behaviour of a loving male adult, they have a harder time becoming a loving male adult themselves - and this can mean bottling up emotions."

In a 2019 survey of England and Wales, 63% of children in Black Caribbean families were found to live in single-parent households - this compares to the lowest ratio of 6% of children in UK Indian families6. This can also be seen in the US, where 58% of black children are raised in a fatherless home, compared to 21% in the white community7.

Continue reading below

Toxic masculinity

Back to contentsBlack men also have to battle with a set of unhealthy and harmful standards that set out what it means to be masculine. This so-called toxic masculinity has existed as a cultural pressure for decades, for men across all ethnicities.

One notion of toxic masculinity is toughness. Expressions such as 'take it like a man' or 'boys don't cry', build the dangerous and unrealistic idea that men should not express emotions that make them look vulnerable, such as being sad or anxious.

Yet, bottling up emotions and following the masculine norms of self-reliance make men more likely to develop depression8, more likely to consider suicide9, and less likely to seek support for their mental health10.

For black men, this is compounded by intergenerational trauma. Historically, black men have opted into toxic masculinity to provide for and protect their families - beginning with slavery and lasting through social structures that have ultimately favoured wealthy white men above everyone else11.

Black masculinity

Experts argue that black masculinity has been a way for black men to form their own culture of dominance, building a barrier between them and racist discrimination.

Counsellor Schubert agrees that the behaviours passed down from father to son are important here. "Again, we can use the example of fatherless households. If there is no positive adult male role model in the home, boys will have a difficult time becoming emotionally mature men."

Outside the family home, the image of black masculinity has seeped into our films and TV shows, sending a clear message to some black men that displays of emotion are frowned upon12.

Accessing mental health support

Back to contentsThese influences leave black men more vulnerable to mental health problems like isolation, loneliness, trauma-related mental conditions, depression, and anxiety. It also makes them less likely to ask for help. For those that do, they may experience some barriers and shortcomings in the care they receive.

An analysis of 66 studies on ethnic inequalities in UK mental healthcare found13:

A lack of socially relevant knowledge in medical training and services, which becomes a barrier when treating mental illnesses linked to experiences of complex trauma, systemic racism, and migration.

Many patients avoid mental healthcare due to fears of racist care and concerns around unsuitable treatment.

Direct experiences of discrimination.

A lack of progress in tackling ethnic inequalities, due to many services not adopting community recommendations.

Ongoing education

Schubert says that for mental health professionals working with marginalised or oppressed communities, ongoing education about cultural and racial diversities is crucial. "By understanding people's diverse backgrounds, professionals can significantly enhance their ability to empathise with, comprehend, and effectively support their clients."

There are also many examples of this in UK healthcare:

The Young Black Men and Mental Health programme is an NHS-funded pioneering programme with Islington Council, in London. Initiatives include a 'Becoming a Man' counselling programme in schools as well as 'Let's talk about race and culture' training sessions for professionals.

Shifting the Dial is a community programme also promoting good mental health in young black men. Based in Birmingham, tactics here involve theatre groups focussed on strengthening mental wellbeing and 'Dear Youngers', a mental health forum offering peer support.

These types of programmes offer valuable blueprints for the future of black mental health support. A report sharing what has been learnt from Shifting the Dial has called for the UK government to tackle all forms of discrimination, including in schools, employment, policing, and healthcare.

It also asks charitable bodies to ensure black-led organisations get fair access to funding, so that these types of programmes can continue to improve black men's mental health support.

What can you do this Movember?

In November 2023, men's health movement Movember is asking people to move for mental health. This means completing a 60km run or walk in November to commemorate the 60 men who kill themselves every hour worldwide. There are also other ways to do your bit for Movember and black men's mental health.

Continue reading below

Further reading

Back to contentsSibrava et al: Posttraumatic stress disorder in African American and Latino adults: clinical course and the role of racial and ethnic discrimination.

US Census Bureau: America’s families and living arrangements.

King et al: Expressions of masculinity and associations with suicidal ideation among young males.

Bansal et al: Understanding ethnic inequalities in mental healthcare in the UK: A meta-ethnography.

Patient picks for Mental wellbeing

Mental health

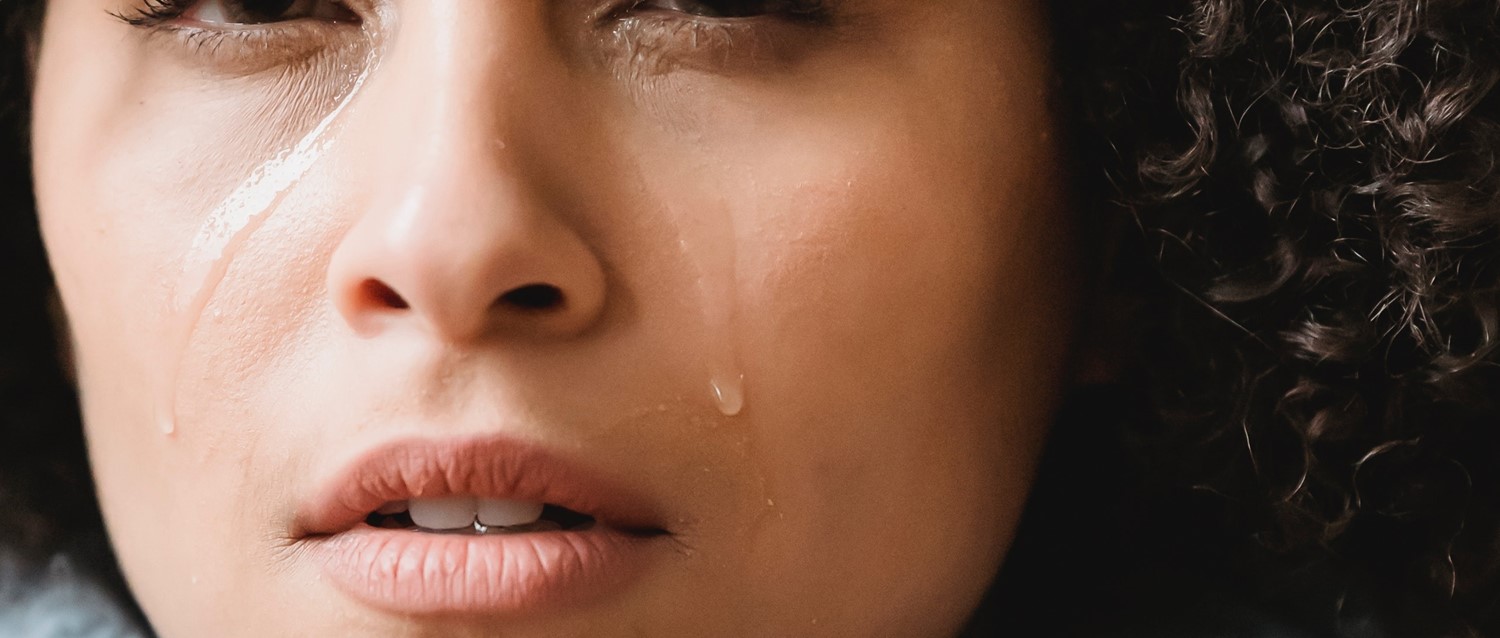

Is crying good for you?

Crying is a completely natural, human process that happens under a variety of circumstances. We cry when we belly laugh, when we grieve, when we're overcome with happiness and at soppy adverts on TV. But is crying actually good for your health? And why is it important to let your tears out when you just need a good bawl?

by Emily Jane Bashforth

Mental health

Building healthy boundaries for a fresh start to the new year

As the new year gets closer, many of us start making big promises about how the next one will be better - getting healthier, earning more, or prioritising what feels most meaningful. But as we cross the finish line of 2025, one thing that can really support your mental wellbeing is setting healthy boundaries. We asked an expert to share some simple, helpful tips for setting better boundaries in the year ahead.

by Victoria Raw

Article history

The information on this page is peer reviewed by qualified clinicians.

2 Nov 2023 | Originally published

Authored by:

Amberley DavisPeer reviewed by

Dr Krishna Vakharia, MRCGP

Ask, share, connect.

Browse discussions, ask questions, and share experiences across hundreds of health topics.

Feeling unwell?

Assess your symptoms online for free

Sign up to the Patient newsletter

Your weekly dose of clear, trustworthy health advice - written to help you feel informed, confident and in control.

By subscribing you accept our Privacy Policy. You can unsubscribe at any time. We never sell your data.