Brachial plexus assessment and common injuries

Peer reviewed by Dr Laurence KnottLast updated by Dr Colin Tidy, MRCGPLast updated 14 Jan 2022

Meets Patient’s editorial guidelines

- DownloadDownload

- Share

- Language

- Discussion

- Audio Version

Medical Professionals

Professional Reference articles are designed for health professionals to use. They are written by UK doctors and based on research evidence, UK and European Guidelines. You may find one of our health articles more useful.

In this article:

Continue reading below

Brachial plexus assessment and common injuries

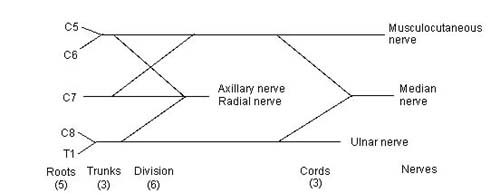

The nerve supply to the arm is from nerve roots C5-T1 via the brachial plexus. The nerves pass under the clavicle and end in the axilla1 .

Brachial plexus

Brachial plexus injuries in adults2

Back to contentsSevere brachial plexus injuries cause dramatic consequences on the motor and sensory functions of the upper limb. The increased incidence of motor vehicle accidents during the past century has been associated with a significant increase in brachial plexus injuries2 .

Milder injuries of the brachial plexus can occur, with transient symptoms and with a full recovery. Milder injuries are more common in some sports, such as martial arts3 .

Signs and symptoms

Traumatic injury mostly occurs in severe road traffic accidents (especially on a motorcycle) and falls from heights. Young men are most commonly affected. The position of the arm (as the injury occurs) will determine the levels involved.

If the arm was held at the side, a C8-T1 injury is usual. However, if the arm is abducted, C7 is commonly involved.

Symptoms are often associated with:

Broken clavicle.

Swelling around the shoulder.

Neck and shoulder pain.

Paraesthesiae and weakness in the arm.

Horner's syndrome, which indicates complete lesion in the lower plexus, ie C5-C7.

Examination

See also the separate Neurological Examination of the Upper Limbs article.

Sensory nerves

Pinch the nail base, pull the finger outwards and ask about feeling anything. A burning feeling indicates continuity in the following nerves; absence does not necessarily mean the nerve is divided but may be due to neurapraxia instead.

Thumb - tests the median nerve supplied by C6.

Middle finger - tests the median nerve supplied by C7.

Little finger - tests the ulnar nerve suppled by C8.

Motor nerves

Examination can be made difficult by anomalous nerve distribution, including C4 contributing to the brachial plexus and also because many muscles are supplied by more than one motor neuron. Assessment of loss of motor function at the cervical root:

C5: shoulder movement in all directions, flexion of elbow (to some degree).

C6: flexion of elbow, rotation of forearm, flexion of wrist (to some degree).

C7: mainly a sensory trunk. (Produces generalised loss of movement in the arm, without total paralysis in any given muscle group. Always supplies the latissimus dorsi.)

C8: extension and flexion of fingers, flexion of wrist, hand movement.

T1: intrinsic muscles of the hand - eg, adduction or abduction of fingers.

Continue reading below

Brachial plexus injuries in neonates

Back to contentsObstetric palsy is classically defined as the brachial plexus injury due to shoulder dystocia or to procedures performed during difficult childbirths. Obstetric palsy occurs in uncomplicated deliveries and in caesarean deliveries, and there are multiple factors that can cause it4 .

Many cases are temporary, with full function recovering within one week. However, permanent injury is not uncommon. See also the separate Birth Injuries to the Baby article.

There are two types of brachial plexus paralysis in neonates: the upper plexus injury is called Erb's palsy; the lower plexus injury is called Klumpke's palsy.

In the UK the incidence is 0.42 per 1,000 live births5 .

They can occur when the head is pulled away from the shoulder during delivery. A small proportion is unrelated to delivery6 .

Risk factors

Large birth weight and/or maternal diabetes.

Shoulder dystocia (increases the risk for brachial plexus injury 100-fold).

Breech presentation.

Multiparity.

Second stage of labour lasting more than 60 minutes.

Assisted delivery.

Intrauterine torticollis.

Examination

Examine 48 hours after delivery for a more reliable assessment.

Erb's palsy (C5-C6 injury) - the arm is characteristically held adducted and internally rotated with the forearm pronated, hand and wrist flexed ('waiter's tip' position). The infant is unable to move the arm or shoulder. See the separate Erb's Palsy article.

Klumpke's palsy - Horner's syndrome is present, ie meiosis, ptosis, anhydrosis.

Investigations2

Back to contentsMyelography, CT myelography, and MRI are indicated for the evaluation of brachial plexus. Electrodiagnostic and nerve conduction studies in association with the clinical findings can provide information regarding the location of the lesion, the severity of trauma, and expected clinical outcome.

High-resolution MRI requires no radiation exposure, is non-invasive and provides more detail than CT myelography7 .

Plain X-rays can be useful to diagnose hemidiaphragm paralysis from phrenic nerve involvement, or fractures of the clavicle or humerus.

Electromyography.

Nerve conduction studies.

Continue reading below

Brachial plexus treatment and management8 9

Back to contentsNerve damage causes a multifaceted clinical picture consisting of sensorimotor disturbances (pain, muscle atrophy, muscle weakness, secondary deformities). Brachial plexus injury may result in severe and chronic impairments for both adults and children. Therefore early treatment and extensive rehabilitation are required. Psychological problems associated with brachial plexus injury may limit rehabilitation effects and increase disability .

General measures

Adult trauma: rehabilitation may play an important role in reducing disability.

Neonatal: spontaneous recovery usually occurs and can start within days but can take months:

Physiotherapy can help10 .

Other treatments include botulinum toxin injection and electrical stimulation11 .

Neuromuscular electrical stimulation (NMES) is a treatment used in an older child, where muscles are stimulated by pulsating alternating currents. It should be titrated with guidance from the child to allow muscle contraction without pain.

Prevention of obstetric injury is not always possible, as a significant proportion of injuries may occur in utero12 .

Surgical

Specialist surgical repair in tertiary centres: options include nerve transfers, nerve grafting, muscle transfers and neurolysis of scar around the brachial plexus13 .

Phrenic nerve transfer has shown useful recovery of arm function in some patients; however, there is very little information about long-term functional and quality-of-life outcomes. There is also some evidence of consequent impairment of respiratory function. However, because patients with brachial plexus injuries are often very disabled and treatment options may be limited, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommends that phrenic nerve transfer may be considered as a treatment option14 .

NICE guidance states the evidence on the safety of free-functioning gracilis transfer to restore upper limb function in brachial plexus injury shows well-recognised complications (pain, bleeding, infection and graft failure). However evidence on its efficacy is adequate to support the use of this procedure. This procedure should only be performed in a specialist brachial plexus unit by a multidisciplinary team including specialised physiotherapists, with input from microvascular surgeons15 .

Arthrodesis of the shoulder may be considered but much more rarely in view of advances with nerve, tendon and free muscle transfers. Wrist arthrodesis may also be considered for wrist pain and gives stability to the hand.

In neonates, surgery is recommended as an early intervention, as outcome is best if repair is undertaken within three months16 .

Complications

Back to contentsProgressive contractures.

Deafferentation pain; this occurs when the nerve roots are avulsed in preganglionic lesions. The cells in the dorsal column are robbed of their nerve supply. After the injury (days to weeks), spontaneous signals are generated by these cells, which result in intractable pain for the patient.

Bony deformities.

Scoliosis.

Posterior shoulder dislocation.

Agnosia of the affected limb.

Further reading and references

- Orebaugh SL, Williams BA; Brachial plexus anatomy: normal and variant. ScientificWorldJournal. 2009 Apr 28;9:300-12.

- Luo TD, Levy ML, Li Z; Brachial Plexus Injuries. StatPearls, August 2021.

- Leinberry CF, Wehbe MA; Brachial plexus anatomy. Hand Clin. 2004 Feb;20(1):1-5.

- Sakellariou VI, Badilas NK, Mazis GA, et al; Brachial plexus injuries in adults: evaluation and diagnostic approach. ISRN Orthop. 2014 Feb 9;2014:726103. doi: 10.1155/2014/726103. eCollection 2014.

- Belviso I, Palermi S, Sacco AM, et al; Brachial Plexus Injuries in Sport Medicine: Clinical Evaluation, Diagnostic Approaches, Treatment Options, and Rehabilitative Interventions. J Funct Morphol Kinesiol. 2020 Mar 30;5(2). pii: jfmk5020022. doi: 10.3390/jfmk5020022.

- Galbiatti JA, Cardoso FL, Galbiatti MGP; Obstetric Paralysis: Who is to blame? A systematic literature review. Rev Bras Ortop (Sao Paulo). 2020 Apr;55(2):139-146. doi: 10.1055/s-0039-1698800. Epub 2020 Jan 9.

- Doumouchtsis SK, Arulkumaran S; Are all brachial plexus injuries caused by shoulder dystocia? Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2009 Sep;64(9):615-23.

- Allen RH, Gurewitsch ED; Temporary Erb-Duchenne palsy without shoulder dystocia or traction to the fetal head. Obstet Gynecol. 2005 May;105(5 Pt 2):1210-2.

- Bhandari PS, Maurya S; Recent advances in the management of brachial plexus injuries. Indian J Plast Surg. 2014 May;47(2):191-8. doi: 10.4103/0970-0358.138941.

- Smania N, Berto G, La Marchina E, et al; Rehabilitation of brachial plexus injuries in adults and children. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2012 Sep;48(3):483-506.

- Pejkova S, Filipce V, Peev I, et al; Brachial Plexus Injuries - Review of the Anatomy and the Treatment Options. Pril (Makedon Akad Nauk Umet Odd Med Nauki). 2021 Apr 23;42(1):91-103. doi: 10.2478/prilozi-2021-0008.

- DiTaranto P, Campagna L, Price AE, et al; Outcome following nonoperative treatment of brachial plexus birth injuries. J Child Neurol. 2004 Feb;19(2):87-90.

- Ramachandran M, Eastwood DM; Botulinum toxin and its orthopaedic applications. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2006 Aug;88(8):981-7.

- Doumouchtsis SK, Arulkumaran S; Is it possible to reduce obstetrical brachial plexus palsy by optimal management of shoulder dystocia? Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010 Sep;1205:135-43. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05655.x.

- Hale HB, Bae DS, Waters PM; Current concepts in the management of brachial plexus birth palsy. J Hand Surg Am. 2010 Feb;35(2):322-31.

- Phrenic nerve transfer in brachial plexus injury; NICE Interventional procedures guidance, Nov 2013

- Free-functioning gracilis transfer to restore upper limb function in brachial plexus injury; Interventional procedures guidance [IPG687]. March 2021.

- Terzis JK, Kokkalis ZT; Outcomes of hand reconstruction in obstetric brachial plexus palsy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008 Aug;122(2):516-26.

Continue reading below

Article history

The information on this page is written and peer reviewed by qualified clinicians.

Next review due: 13 Jan 2027

14 Jan 2022 | Latest version

Ask, share, connect.

Browse discussions, ask questions, and share experiences across hundreds of health topics.

Feeling unwell?

Assess your symptoms online for free