Osteoporosis

Peer reviewed by Dr Colin Tidy, MRCGPLast updated by Dr Hayley Willacy, FRCGP Last updated 29 Dec 2021

Meets Patient’s editorial guidelines

- DownloadDownload

- Share

- Language

- Discussion

- Audio Version

Medical Professionals

Professional Reference articles are designed for health professionals to use. They are written by UK doctors and based on research evidence, UK and European Guidelines. You may find the Osteoporosis article more useful, or one of our other health articles.

In this article:

Continue reading below

What is osteoporosis?

Osteoporosis is a progressive systemic skeletal disease characterised by reduced bone density and micro-architectural deterioration of bone tissue. As a result, bone is increasingly fragile and more susceptible to fracture.

Osteoporotic (fragility) fractures are fractures that result from mechanical forces that would not ordinarily result in fracture. Osteoporotic fractures are defined as fractures associated with low bone mineral density (BMD) and include spine, forearm, hip and shoulder fractures.

For clinicians, managing osteoporosis is a challenge due to conflicting guidelines and as yet incomplete evidence (and therefore guidance) in important areas.

Bone density

Back to contentsBone density values in individuals can be expressed in relation to a reference population in standard deviation (SD); when SDs are used in relation to the young healthy population, this measurement is referred to as the T score. A Z score compares bone density to the normal at that age, and a score of -2 indicates bone density below normal for a person of that age.

BMD categories established by the World Health Organization (WHO):

Normal: hip BMD greater than the lower limit of normal which is taken as 1 SD below the young adult reference mean (T score ≥-1).

Low bone mass (osteopenia): hip BMD between 1 and 2.5 SD below the young adult reference mean (T score less than -1 but above -2.5).

Osteoporosis: hip BMD 2.5 SD or more below the young adult reference mean (T score ≤-2.5).

Severe osteoporosis: hip BMD 2.5 SD or more below the young adult reference mean in the presence of one or more fragility fractures (T score ≤-2.5 PLUS fracture).

Bone density can be measured by a number of investigative tests but the one most commonly used is dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (now abbreviated to DXA). See the 'Investigations' section below for further details.

Continue reading below

Who gets osteoporosis? (Epidemiology)1

Back to contentsIn England and Wales more than 2 million women have osteoporosis.

In England and Wales there are around 180,000 fractures per year due to osteoporosis.

1 in 3 women and 1 in 5 men will have an osteoporotic fracture in their lifetime.

Osteoporosis is in general an age-related disease. Bone formation initially exceeds bone resorption but by the third decade this has reversed resulting in a net loss of bone mass. Therefore, bone mass declines with age and this is accelerated for a time in women after menopause. Prevalence of osteoporosis increases markedly with age, from 2% at 50 years to more than 25% at 80 years in women.2

Risk factors for fragility fractures3

Reduced BMD is a major risk factor for fragility fracture.

As well as reduced BMD, a number of other risk factors increase fracture risk. Some do this by increasing the risk of osteoporosis, some are independent risk factors and some work in more than one way. Identification of these risk factors is important as it guides case-finding and treatment.

Increasing age (risk increased partly independent of reducing BMD).

Female sex.

Low body mass (<19 kg/m2) and anorexia nervosa.

Parental history of hip fracture.

Past history of fragility fracture (especially hip, wrist and spine fracture).

Corticosteroid therapy (current treatment at any dose orally for three months or more).

Alcohol intake of three or more units per day.

Smoking.

Falls and conditions increasing the risk of falls, such as:

Visual impairment.

Lack of neuromuscular co-ordination or strength.

Cognitive impairment.

Sedative medication and alcohol.

Secondary osteoporosis causes, such as:

Rheumatoid arthritis and other inflammatory arthropathies.

Prolonged immobilisation or a very sedentary lifestyle.

Primary hypogonadism (men and women).

Post-transplantation.

Gastrointestinal disease such as Crohn's disease, ulcerative colitis and coeliac disease.

Untreated premature menopause (<45 years) or prolonged secondary amenorrhoea.

Chronic liver disease.

Osteoporosis symptoms

Back to contentsUnfortunately, the process that leads to established osteoporosis is asymptomatic and the condition usually presents only after bone fracture. It is important that clinicians be alert to recognise low-trauma 'fragility fractures' (fracture caused by a force equivalent to the force of a fall from the height of an ordinary chair or less).

Fragility fractures occur most commonly in the spine (vertebrae), hip (proximal femur) and wrist (distal radius). They may also occur in the arm (humerus), pelvis, ribs and other bones.2 Signs differ according to the fracture site.

Continue reading below

Investigations2 4

Back to contentsSee also the separate Osteoporosis Risk Assessment and Primary Prevention article.

Osteoporosis diagnosis

Diagnosis of osteoporosis centres on the assessment of BMD. DXA (or DEXA stands for dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry) is regarded as the gold standard technique for diagnosis. The accuracy at the hip exceeds 90%. Residual errors arise for various reasons. Incorrect diagnosis of osteoporosis can be caused by osteomalacia, osteoarthritis or soft-tissue calcification.

The WHO, the International Osteoporosis Foundation (IOF) and the National Osteoporosis Guideline Group (NOGG) recommend the use of DXA at the hip for the diagnosis of osteoporosis. Other radiological investigations sometimes used for screening purposes are:5

Single-energy X-ray absorptiometry (SXA).

Digital X-ray radiogrammetry (DXR). DXR is simpler and less time-consuming than DXA. It can be carried out anywhere where there is the facility to perform a standard radiograph of the hand. It may be used as a screening tool for osteoporosis (for example, following Colles'/other forearm fractures), without the need for additional radiographs.

Ultrasonic measurement of bone, usually measured at the heel. This can be used for the assessment of fracture risk or for selection of those in need of DXA. It is unreliable for diagnosis of osteoporosis and is associated with underdiagnosis.

Consider the following screening blood tests, in patients suffering from osteoporosis, to identify treatable underlying causes of osteoporosis and to rule out differential diagnoses (osteomalacia, myeloma):

FBC and ESR or CRP.

U&E, LFTs, TFTs, serum calcium.

Testosterone/gonadotrophins in men.

Serum immunoglobulins and paraproteins, urinary Bence-Jones' proteins.

Assessment of fracture risk

Although osteoporosis indicates a high likelihood of fracture, many fragility fractures occur in people with bone density values above the defined level. Measurements of BMD by DXA at the lumbar spine, femoral neck, total hip and wrist have been shown to predict future fracture occurrence. Peripheral DXA has some predictive value but less so than measurements at the hip and spine.4 The use of BMD alone to assess risk, however, has a high specificity but low sensitivity and most osteoporotic fractures will occur in people who do not have osteoporosis as defined by a T score of ≤2.5. Fractures can be better predicted by adding clinical risk factors that contribute to fracture risk independently of BMD. BMD should not therefore normally be routinely measured without the prior use of a risk assessment tool as follows.

The WHO risk calculator available (FRAX®) calculates the ten-year probability of a major osteoporotic fracture in people aged 40-90 (with or without BMD result). The result then leads to a position on a chart of low, intermediate and high risk and subsequent NOGG advice as to the need for treatment.

For UK populations, the QFracture® score may be more appropriate for fracture risk assessment as it was based on UK data.3 It may be used for ages 30-99 and does not include BMD.

NOGG guidelines advocate the use of FRAX®, whilst National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines allow for use of either FRAX® or QFracture® but advise FRAX® where BMD is available. Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) guidelines encourage the use of QFracture prior to BMD measurement as a risk calculation tool.

Case finding

There is no national screening protocol for osteoporosis. Guidelines from NOGG, NICE, SIGN and IOF differ, making it difficult for the clinician to choose whom to carry out risk assessments or BMD measurement upon. Broadly, consider a risk assessment in:

Those with a history of fragility fracture. Some guidelines suggest this should trigger BMD measurement; others suggest these should be considered for treatment without the need for further assessment.

Postmenopausal women with risk factors.

Women or men with significant risk factors.

Women or men on oral corticosteroid treatment. (Any dose taken continuously over three months or frequent courses. 7.5 mg prednisolone or equivalent per day over three months continuously is considered high dose by NICE and confers higher risk.)

All women over 65 and all men over 75 (NICE only).

Osteoporosis treatment and management1

Back to contentsGeneral

As osteoporosis is an asymptomatic condition, management is centred on preventing fragility fractures, which are associated with enormous morbidity and mortality. Treatment for osteoporosis should include not only drug treatment but also advice on lifestyle, nutrition, exercise and measures to reduce falls. Advise on smoking cessation where indicated, and moderation of alcohol intake. Advise regular weight-bearing exercise. Evidence suggests this has a modest but significant effect in improving bone density.6

Assess for risk of falls and consider referral to a falls prevention service. Consider hip protectors. Reduce polypharmacy, especially sedatives.

Calcium and vitamin D

Ensure adequate calcium intake and vitamin D status, prescribing supplements if required.7 Dietary calcium may be assessed by one of a number of online tools.8 9 Elderly people who are housebound or living in a nursing home may be assumed to require vitamin D supplementation. If there is adequate dietary calcium intake of more than 1000 mg/day but a lack of vitamin D, consider prescribing 10 micrograms (400 units) of vitamin D without a full replacement dose of calcium. For people who have a dietary calcium intake of less than 1000 mg/day, prescribe 10 micrograms (400 units) of vitamin D with at least 1000 mg of calcium daily (eg, as two Calcichew D3® tablets - calcium 500 mg, colecalciferol 5 micrograms). There is ongoing research into the safety of calcium supplementation but no risk has been found where calcium is combined with vitamin D and, thus far, evidence suggests combined calcium and vitamin D are more effective than vitamin D alone in preventing fractures.10 Additionally it has been shown that vitamin D supplementation does not prevent fractures or falls or have clinically meaningful effects on bone mineral density.11

The detail in the following two sections reflects NICE guidance. NOGG thresholds do not differentiate between primary and secondary prevention, other than where previous fragility fractures affect the FRAX® score upon which management advice is based. To follow NOGG guidelines on whether to treat or not, simply follow the algorithm following risk calculation in the FRAX® link above. Once the FRAX® risk has been calculated, your patient will be placed in a category on an intervention chart which will advise on subsequent management (low risk: lifestyle advice; intermediate risk: measure BMD and recalculate risk; high risk: consider treatment).

Further osteoporosis management in postmenopausal women who have never had an osteoporotic fragility fracture (primary prevention)12

Bisphosphonates

NICE recommends that oral bisphosphonates (alendronic acid, ibandronic acid and risedronate sodium) are options for treating osteoporosis in adults, only if the person is eligible for risk assessment as defined in NICE's guideline on osteoporosis and the 10‑year probability of osteoporotic fragility fracture (as calculated either using FRAX® or QFracture®) is at least 1%.13

The first-line bisphosphonate is usually alendronate on the basis of cost.

Bisphosphonate treatment is only recommended in postmenopausal women aged under 65 with confirmed osteoporosis but without fragility fractures, if they have an independent clinical risk factor for fracture and at least one additional indicator of low BMD.

Start bisphosphonates in osteoporotic women without fragility fracture once they reach age 65 if they have any independent clinical risk factor for fracture, or over the age of 70 if they just have an indicator of low BMD.

The responsible physician may decide a DXA scan is not required in women aged 75 years or older who have two or more independent clinical risk factors for fracture or indicators of low BMD.

Other osteoporosis treatments

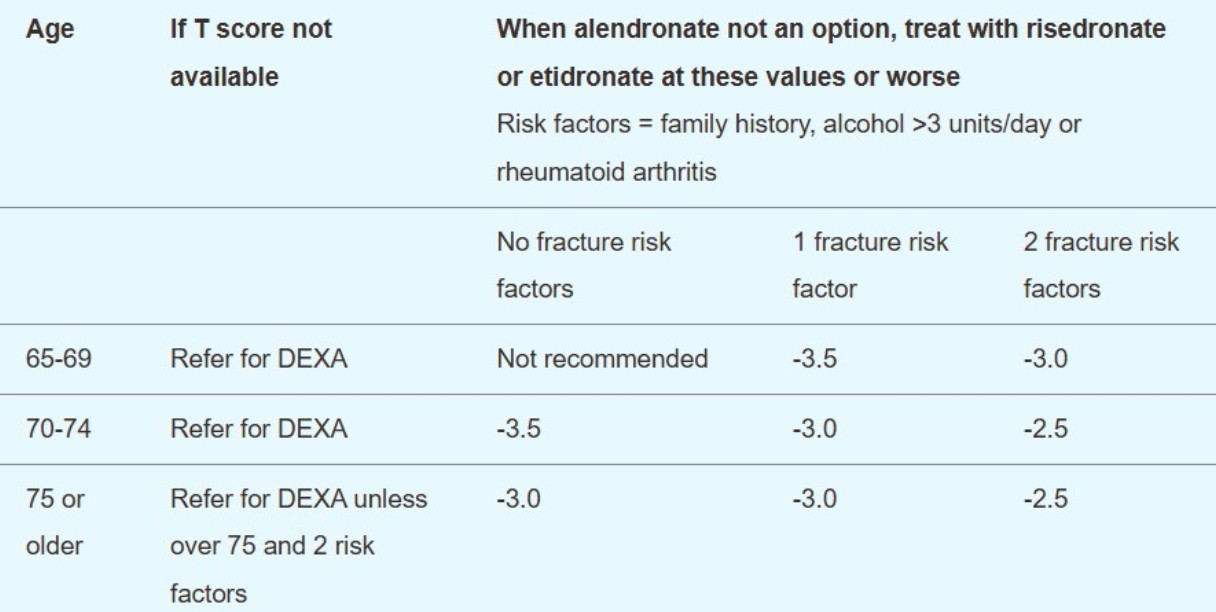

Second-line treatments (risedronate and etidronate) may be considered if the patient is aged over 65 and unable to take alendronate:

Primary prevention - T-score treatment threshold for second-line treatment in patients without previous fragility fracture

Denosumab is a monoclonal antibody that reduces osteoclast activity (and hence bone breakdown) which is given by six-monthly subcutaneous injections. It may be a suitable option in women who are unable to comply with instructions for alendronate and either risedronate or etidronate.

Primary prevention - T-score treatment threshold for denosumab treatment in patients without previous fragility fracture14

Age | Number of independent clinical risk factors for fracture Parental history of hip fracture, alcohol intake of four or more units per day and rheumatoid arthritis | ||

| No fracture risk factors | 1 fracture risk factor | 2 fracture risk factors |

65-69 | Not recommended | -4.5 | -4.0 |

70-74 | -4.5 | -4.0 | -3.5 |

75 or older | -4.0 | -4.0 | -3.0 |

Strontium ranelate was licensed for the prevention of osteoporotic fractures in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis, but the European Medicines Agency (EMA) advised that it should only be used where other medications were not tolerated and there are few cardiovascular risk factors.15 The manufacturer decided to withdraw strontium worldwide because the number of patients treated with the drug declined. GPs are advised to identify and review any patients who are currently prescribed strontium ranelate and discuss alternative treatment options with them.

Raloxifene is not recommended as a treatment option for the primary prevention of osteoporotic fragility fractures.

Further osteoporosis management in postmenopausal women who have had an osteoporotic fragility fracture (secondary prevention)16

Bisphosphonates. Start first-line bisphosphonate (usually alendronate on the basis of cost) and consider calcium and vitamin D supplementation. If the initial alendronate is not tolerated or is inappropriate, or there is an inadequate response, the next step depends on BMD, age and risk factors:

Secondary prevention - T-score treatment threshold for second-line treatment in patients with previous fragility fracture

Age | If T score not available | When alendronate not an option, treat with risedronate or etidronate at these values or worse12

Risk factors = family history, alcohol above three units/day or rheumatoid arthritis | ||

|

| No fracture risk factors | 1 fracture risk factor | 2 fracture risk factors |

50-54 | Refer for DXA | Not recommended | -3.0 | -2.5 |

55-59 | Refer for DXA | -3.0 | -3.0 | -2.5 |

60-64 | Refer for DXA | -3.0 | -3.0 | -2.5 |

65-69 | Refer for DXA | -3.0 | -2.5 | -2.5 |

70-74 | Refer for DXA | -2.5 | -2.5 | -2.5 |

75 and over | DXA may not be required (see any local guidelines) | -2.5 | -2.5 | -2.5 |

Raloxifene. If second bisphosphonate is not an option, treat with raloxifene at these thresholds:

Secondary prevention - T-score treatment threshold for third-line treatment in patients with previous fragility fracture

Threshold for treatment with raloxifene Risk factors = family history, alcohol more than three units/day or rheumatoid arthritis | |||

Age | 0 risk factors | 1 risk factor | 2 risk factors |

50-54 | Not recommended | -3.5 | -3.5 |

55-59 | -4.0 | -3.5 | -3.5 |

60-64 | -4.0 | -3.5 | -3.5 |

65-69 | -4.0 | -3.5 | -3.0 |

70-74 | -3.0 | -3.0 | -2.5 |

75 and over | -3.0 | -2.5 | -2.5 |

If raloxifene is not an option, consider referral to secondary care for assessment for teriparatide or denosumab:

Strontium has now been withdrawn by the manufacturer.

Denosumab may also be a treatment option for the secondary prevention with increased risk of fractures in patients who cannot comply with the special instructions for administering alendronate, risedronate or etidronate, or have an intolerance or a contra-indication to those treatments.14

Teriparatide is a recombinant fragment of parathyroid hormone prescribed in secondary care. It may be considered if the woman is:

Unable to take or has a contra-indication to or intolerance of alendronate and an alternative bisphosphonate.

Proven to have an unsatisfactory response to a bisphosphonate.

65 or older with:

A T score of -4 SD or below; or

A T score of -3.5 SD or below plus a history of more than two fractures.

55-65 with a T score of -4 SD or below plus a history of more than two fractures.

Romosozumab is a monoclonal antibody that increases bone formation, and decreases bone resorption. This anabolic or bone-forming therapy has a novel mechanism of action that differs from that of teriparatide. Romosozumab is given in a monthly dose of 210 mg subcutaneously for 12 months followed by a transition to antiresorptive therapy with the aim of maintaining the increase in BMD.

Editor's note |

|---|

Dr Krishna Vakharia, 27th May 2022 Romosozumab for treating severe osteoporosis17 Who are postmenopausal; and Who have had an osteoporotic fracture (spine, hip, forearm or humerus fracture) within 24 months (so are at imminent risk of another fracture). Clinical trial evidence suggests that romosozumab followed by alendronic acid is more effective at reducing the risk of fractures than alendronic acid alone. Comparing romosozumab indirectly with other bisphosphonates and other medicines for this condition suggests that romosozumab is likely to be at least as effective at reducing the risk of fractures in people with osteoporosis after menopause. Dr Krishna Vakharia, 15th August 2024 |

Osteoporosis in men and premenopausal women4 5

Treatment for men is less well evaluated and researched and not as extensively covered by guidelines. Management would normally be undertaken in secondary care. Alendronate, risedronate, zoledronic acid, teriparatide and strontium are approved for the treatment of osteoporosis in men. Osteoporosis is more likely to be related to a secondary cause in men, so investigation for an underlying cause is important.

Hormone replacement therapy (HRT) has an unfavourable risk:benefit ratio for older postmenopausal women but may be used for the prevention and treatment of osteoporosis in women with premature menopause or in younger postmenopausal women who have symptoms of menopause.

Pharmacological treatments for osteoporosis7

Back to contentsThere have been no head-to-head trials of the treatment options for osteoporosis, so it is not known which is most effective.

Bisphosphonates

These are the mainstay of treatment. Bisphosphonates act by inhibiting the action of osteoclasts. They are, however, poorly absorbed and need to be taken separately from food. They may cause oesophageal irritation and should be taken by the patient sitting up with plenty of water. Etidronate was the first but has been superseded by the more powerful alendronate and risedronate, both of which can be taken daily or weekly, and the newer ibandronate that can be taken monthly. Less frequent dosing may improve adherence to therapy. All bisphosphonate trials have been controlled for calcium/vitamin D and so bisphosphonates have usually historically had calcium/vitamin D co-prescribed. This practice, however, is less clear in light of more recent concerns about calcium supplementation, and if there is evidence of adequate dietary calcium and adequate vitamin D status, it is probably best avoided.

Zoledronic acid (Aclasta®)

This is the most potent bisphosphonate, given by a single intravenous infusion once a year, and licensed for the treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis and osteoporosis in men. It is very expensive compared with oral formulations.19

The main adverse effects/concerns relating to bisphosphonates are:

Gastrointestinal adverse effects.

Poor adherence to treatment (partly due to complex instructions about taking them - the tablet is taken first thing in the morning on an empty stomach with a large glass of water. The person should be sitting upright or standing when the tablet is taken and must not lie down, eat or take other oral medication for at least 30 minutes afterwards (60 minutes for ibandronate). Most are taken on a weekly basis).

Osteonecrosis of the jaw.20

Atypical femoral fractures.

Possible increased risk of atrial fibrillation and oesophageal cancer (evidence currently inconclusive and suggests an association rather than cause).4

Raloxifene

This a selective oestrogen receptor modulator (SERM), reduces postmenopausal bone loss and reduces vertebral fractures but, like HRT, may increase the risk of venous thromboembolism. Unlike HRT, however, it decreases the risk of breast cancer (oestrogen-positive tumours) but may exacerbate hot flushes. The Commission on Human Medicines (CSM) has advised that HRT should not be considered as first-line therapy for long-term prevention of osteoporosis, due to the increased risk of breast cancer and cardiovascular disease.

Parathyroid hormone peptides

These are given by subcutaneous injection daily for a maximum of two years (course not to be repeated). Evidence of efficacy exists for vertebral but not hip fractures. Expense restricts their use. They may be considered as an alternative for men or women in whom alendronate and either risedronate or etidronate are contra-indicated or not tolerated, or where treatment with one of these options has been unsatisfactory (another fragility fracture and a decline in BMD despite treatment for one year).

Teriparatide (recombinant 1-34 parathyroid hormone) (Forsteo®).

Parathyroid hormone (the full 1-84 parathyroid hormone peptide) (Preotact®).

Treatment of fractures21 22

Back to contentsWhere fractures have occurred, these are managed in accordance with relevant guidance. Treatment of fractures is discussed in the related separate articles Femoral Fractures, Wrist Fractures, etc.

Recently, surgical procedures for the treatment of vertebral compression fractures have been approved by NICE. Compression fractures cause:

Pain and morbidity associated with high doses of analgesia.

Loss of height.

Difficulty breathing.

Loss of mobility.

Gastrointestinal symptoms.

Difficulty sleeping.

Symptoms of depression.

Management aims to reduce these problems and options include:

Analgesia.

Back braces.

Physiotherapy.

Percutaneous vertebroplasty - injection of bone cement into the vertebral body.

Balloon kyphoplasty - inflation of a balloon-like device into the vertebral body to restore its height, followed by injection of bone cement.

NICE advises the latter surgical options only in those with severe pain despite conservative measures, and where it has been confirmed that the pain is due to the fracture. A 2018 Cochrane review advises however that patients should be informed about both the high- to moderate-quality evidence that shows no important benefit of vertebroplasty and its potential for harm.23

Length of osteoporosis treatment24

Back to contentsOne of the currently difficult areas for primary care clinicians managing people with osteoporosis is to know how to monitor treatment and when to stop it. There is no consensus on how often BMD should be measured for individuals on treatment; guidelines generally suggest between three and five years.

Bisphosphonates bind to bone mineral and inhibit osteoclastic bone resorption. Continual bone remodelling is important in maintaining a healthy skeleton by repairing microdamage, and there has been a theoretical concern that prolonged treatment could potentially have a weakening effect on bone. Furthermore, the bisphosphonates are retained in bone for some time after treatment is stopped, and the effects can continue for months or years after treatment has been stopped.

It is clear that there should be a review of the need for treatment vs the risks at some point, and this is mostly agreed to be after around five years. Where risk factors have changed (steroid treatment discontinued, for example, or T score above -2.5), this becomes a simple decision; however, in the majority of cases it is not so straightforward.

At this time, NOGG has the most clear algorithm to help determine whether to continue treatment at this point. It advises:

Review after five years of bisphosphonate treatment (three years for zoledronic acid).

If there have been recurrent fractures:

Check adherence.

Exclude secondary causes.

Reconsider treatment choice.

Continue treatment.

If no fractures, re-measure BMD and FRAX®:

If T score at femoral neck ≤-2.5 or above NOGG intervention threshold:

Check adherence.

Exclude secondary causes.

Reconsider treatment choice.

Continue treatment.

If T score at femoral neck >-2.5 or results are below NOGG intervention threshold, consider a drug holiday. Repeat BMD and FRAX® in two years.

Generally the following are likely to need to continue treatment at five years:

Those aged 75 years or more.

Those who have previously sustained a hip or vertebral fracture.

Those on continuous oral glucocorticoids in a dose of 7.5 mg/day prednisolone or equivalent.

Those who have had one or more low-trauma fractures during treatment, after exclusion of poor adherence to treatment (for example, less than 80% of treatment has been taken) and after causes of secondary osteoporosis have been excluded. In such cases the treatment option should be re-evaluated.

Those in whom the total hip or femoral neck BMD T score is ≤-2.5 SD.

When treatment is discontinued, reassess fracture risk after two years, or earlier if a fragility fracture is sustained.

Prognosis2 5

Back to contentsOsteoporotic fragility fractures can cause substantial pain and severe disability, often leading to a reduced quality of life, and hip and vertebral fractures are associated with decreased life expectancy.

Hip fracture nearly always requires hospitalisation, is fatal in 20% of cases and permanently disables 50% of those affected; only 30% of patients fully recover. Surgery carries risks of complications. Fixation failure is more likely to be a problem in osteoporotic bone.

Vertebral fractures are often undiagnosed. They are associated with long-term pain and disability. One study found a year after the event, four out of five people with vertebral fracture still had significant pain and loss of quality of life.25 One vertebral fracture increases a patient's risk of sustaining another vertebral fracture five-fold - 20% of these within a year.

Osteoporotic fractures in general cause severe pain and disability to individuals who sustain them, at an annual cost to the NHS of over £1.73 billion.

Further reading and references

- Falls: assessment and prevention of falls in older people; NICE Clinical Guideline (June 2013) (Replaced by NG249)

- EULAR/EFORT recommendations for management of patients older than 50 years with a fragility fracture and prevention of subsequent fractures; European League against Rheumatism (2017)

- Liu GF, Wang ZQ, Liu L, et al; A network meta-analysis on the short-term efficacy and adverse events of different anti-osteoporosis drugs for the treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis. J Cell Biochem. 2018 Jun;119(6):4469-4481. doi: 10.1002/jcb.26550. Epub 2018 Feb 28.

- Osteoporosis - prevention of fragility fractures; NICE CKS, July 2021 (UK access only)

- Osteoporosis: assessing the risk of fragility fracture; NICE Clinical Guideline (August 2012, updated February 2017)

- QFracture®-2016 risk calculator

- Management of osteoporosis and the prevention of fragility fractures - A national clinical guideline; Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN - January 2021)

- Clinical guideline for the prevention and treatment of osteoporosis; National Osteoporosis Guideline Group (NOGG - 2017)

- Howe TE, Shea B, Dawson LJ, et al; Exercise for preventing and treating osteoporosis in postmenopausal women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011 Jul 6;(7):CD000333. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000333.pub2.

- Poole KE, Compston JE; Bisphosphonates in the treatment of osteoporosis. BMJ. 2012 May 22;344:e3211. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e3211.

- Dietary Calcium Calculator; International Osteoporosis Foundation

- Rheumatological diseases unit: Calcium Calculator; Institute of Genetics and Molecular Medicine (IGMM), University of Edinburgh

- Avenell A, Mak JC, O'Connell D; Vitamin D and vitamin D analogues for preventing fractures in post-menopausal women and older men. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014 Apr 14;4:CD000227. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000227.pub4.

- Mark J Bolland, PhD et al; Effects of vitamin D supplementation on musculoskeletal health: a systematic review, meta-analysis, and trial sequential analysis, The Lancet, October 2018.

- Alendronate, etidronate, risedronate, raloxifene and strontium ranelate for the primary prevention of osteoporotic fragility fractures in postmenopausal women (amended); NICE Technology appraisal guidance, last updated February 2018

- Bisphosphonates for treating osteoporosis; NICE Technology appraisal guidance, August 2017 - last updated July 2019

- Denosumab for the prevention of osteoporotic fractures in postmenopausal women; NICE Technology appraisal guidance, October 2010

- Strontium ranelate: cardiovascular risk. Drug Safety update; GOV.UK, March 2014

- Alendronate, etidronate, risedronate, raloxifene, strontium ranelate and teriparatide for the secondary prevention of osteoporotic fragility fractures in postmenopausal women; NICE Technology Appraisal Guidance, January 2011

- Romosozumab for treating severe osteoporosis; NICE Technology appraisal guidance, May 2022

- Abaloparatide for treating osteoporosis after menopause; NICE Technology appraisal guidance, August 2024

- Summary of Product Characteristics (SPC) - Aclasta® 5 mg solution for infusion; Novartis Pharmaceuticals UK Ltd, electronic Medicines Compendium, May 2015

- Sturrock A, Preshaw PM, Hayes C, et al; Attitudes and perceptions of GPs and community pharmacists towards their role in the prevention of bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaw: a qualitative study in the North East of England. BMJ Open. 2017 Sep 29;7(9):e016047. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-016047.

- Percutaneous vertebroplasty and percutaneous balloon kyphoplasty for treating osteoporotic vertebral compression fractures; NICE Technology Appraisal Guidance, April 2013

- Dionyssiotis Y; Management of osteoporotic vertebral fractures. Int J Gen Med. 2010 Jul 21;3:167-71.

- Buchbinder R, Johnston RV, Rischin KJ, et al; Percutaneous vertebroplasty for osteoporotic vertebral compression fracture. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018 Nov 6;11:CD006349. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006349.pub4.

- Maraka S, Kennel KA; Bisphosphonates for the prevention and treatment of osteoporosis. BMJ. 2015 Sep 2;351:h3783. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h3783.

- Suzuki N, Ogikubo O, Hansson T; The prognosis for pain, disability, activities of daily living and quality of life after an acute osteoporotic vertebral body fracture: its relation to fracture level, type of fracture and grade of fracture deformation. Eur Spine J. 2009 Jan;18(1):77-88. doi: 10.1007/s00586-008-0847-y. Epub 2008 Dec 12.

Continue reading below

Article history

The information on this page is written and peer reviewed by qualified clinicians.

Next review due: 28 Dec 2026

29 Dec 2021 | Latest version

Ask, share, connect.

Browse discussions, ask questions, and share experiences across hundreds of health topics.

Feeling unwell?

Assess your symptoms online for free