Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome

Peer reviewed by Dr Philippa Vincent, MRCGPLast updated by Dr Toni Hazell, MRCGPLast updated 17 Sept 2024

Meets Patient’s editorial guidelines

- DownloadDownload

- Share

- Language

- Discussion

- Audio Version

Medical Professionals

Professional Reference articles are designed for health professionals to use. They are written by UK doctors and based on research evidence, UK and European Guidelines. You may find one of our health articles more useful.

In this article:

Continue reading below

What is Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome?

Wolff-Parkinson-White (WPW) syndrome is the most common of the ventricular pre-excitation syndromes. Others include Lown-Ganong-Levine syndrome and Mahaim-type pre-excitation.

They are important because of the association with paroxysmal tachycardias that can result in serious cardiovascular complications and sudden death. In ECG terms they are important to recognise because of the risk of misdiagnosis.

WPW syndrome was first described by Drs Wolff, Parkinson and White in 1930.1

WPW syndrome is a congenital abnormality which can result in supraventricular tachycardia (SVT) that uses an atrioventricular (AV) accessory tract. The accessory pathway may also allow conduction during other supraventricular arrhythmias, such as atrial fibrillation or flutter. The majority of patients with ECG findings of pre-excitation do not develop tachyarrhythmias. WPW syndrome is classified into two types according to the ECG findings:

Type A: the delta wave and QRS complex are predominantly upright in the precordial leads. The dominant R wave in lead V1 may be misinterpreted as right bundle branch block.

Type B: the delta wave and QRS complex are predominantly negative in leads V1 and V2 and positive in the other precordial leads, resembling left bundle branch block.

Causes of Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome

Back to contentsAn accessory pathway is likely to be congenital, although it presents in later years and may appear to be acquired.

The pattern arises from the fusion of ventricular pre-excitation through the accessory pathway and normal electrical conduction through the AV node.2

May be associated with congenital cardiac defects, Ebstein's anomaly, mitral valve prolapse, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy or other cardiomyopathies.

Continue reading below

How common is Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome? (Epidemiology)

Back to contentsWPW syndrome is relatively common and found in 1-3 people per 1,000 population.2

Familial studies have shown a slightly higher incidence of WPW, about 0.55% among first-degree relatives of an index patient with WPW, however symptomatic WPW (known as WPW syndrome) is more common in males.3

WPW syndrome is found in all ages, although it is most common in young, previously healthy people. Prevalence decreases with age because of loss of pre-excitation.

WPW syndrome is a developmental anomaly as well as a congenital anomaly. WPW syndrome in infancy often disappears and may recur in later childhood. Studies suggest that the prevalence of WPW syndrome is significantly lower in children aged 6-13 years than in those aged 14-15 years.4

Symptoms of Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome (presentation)2

Back to contentsSVT in WPW syndrome may begin in childhood or not appear clinically until middle age.

Asymptomatic: may be detected on incidental ECG.

Symptomatic: palpitations, light-headedness or syncope.

In one study of patients under 21 years or age with WPW on ECG, 64% had symptoms at presentation and 20% developed symptoms during follow-up.5

The tachycardia that produces symptoms may be an SVT, atrial fibrillation or atrial flutter.

Paroxysmal SVT can be followed after termination by polyuria, which is due to atrial dilatation and release of atrial natriuretic factor.

Sudden death: from deterioration of pre-excited atrial fibrillation into ventricular fibrillation (this is rare and discussed in more detail later in the leaflet).

During SVT, the rhythm is constant and regular, with constant intensity of the first heart sound.

The jugular venous pressure may be elevated but the waveform remains constant.

Clinical features of associated cardiac defects may be present - eg, mitral valve prolapse, cardiomyopathy.

Continue reading below

Differential diagnosis6

Back to contentsAtrioventricular nodal re-entry tachycardia (AVNRT).

Sinus node dysfunction.

Other causes of syncope.

Diagnosing Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome (investigations)

Back to contentsECG7

WOLFF-PARKINSON-WHITE SYNDROME

The electrical impulse may travel at the same speed as along the normal system (bundle of His), with no pre-excitation and the ECG is normal. The condition is described as latent, until the rate exceeds the refractory period of the AV node.

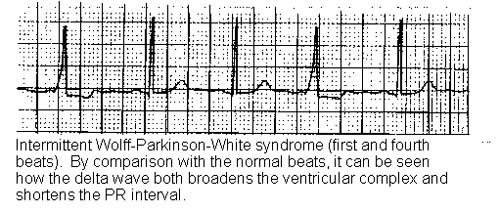

Classic ECG findings of WPW syndrome include a short PR interval (less than 120 ms), a prolonged QRS complex of longer than 120 ms with a slurred onset producing a delta wave in the early part of QRS and secondary ST-T wave changes.28

Repolarisation abnormalities are common in patients with WPW syndrome.

AV re-entry tachycardia, or circus movement tachycardia:

The accessory pathway only conducts in a retrograde manner and the condition remains latent until triggered.

A premature atrial extrasystole, finding the accessory pathway refractory, travels via the AV node, with reactivation back from the ventricles along the accessory pathway (retrograde conduction), if time has allowed recovery of excitability.

Therefore, a circuit is established, being seen as a tachycardia, with normal QRS but with inverted P waves (because of retrograde atrial activation).

Pre-excited atrial fibrillation:

Conduction is rapid, avoiding any rate-limiting effect of the AV node, the accessory pathway having a much shorter anterograde refractory period. Ventricular response is thus not limited.

Hypotension, by causing a sympathetic response, can further shorten the refractory period and ventricular fibrillation may result.

The appearance is irregular, variable QRS (normal to wide complex), at rates often around 250 beats per minute.

There is a much rarer form of AV tachycardia with anterograde conduction via the accessory pathway and retrograde conduction via the AV node, seen as a regular, rapid, broad-complex tachycardia.

Other investigations

A variety of recording devices can be used if arrhythmias are infrequent, including Holter monitors, event monitors and implantable loop recorders. In general, monitoring needs to be at a frequency related to symptoms - eg, if symptoms occur every few days, 24-hour monitoring is unlikely to be helpful.

Stress testing may help to diagnose transient paroxysmal dysrhythmia, determine the relationship between exercise and tachycardia or evaluate the effect of medication.

Routine blood tests may be needed to help rule out non-cardiac conditions triggering tachycardia - eg, FBC, U&E and creatinine, LFTs, TFTs and blood levels of anti-arrhythmic drugs.

Echocardiogram: may be needed to assess left ventricular function and wall motion and to help rule out valvular disease, Ebstein's anomaly, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (in which the incidence of accessory pathways is increased), or other congenital cardiac defects.

Intracardiac or oesophageal electrophysiological studies may be useful in identifying accessory pathways and during surgery to map areas that require ablation.

Management of Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome25

Back to contentsAsymptomatic patients may just need periodic review, but should be clearly told to seek urgent medical help if they experience palpitations or syncope. The decision on whether to treat or adopt a 'watch and wait' strategy should be made by a cardiologist. Factors favouring treatment, for example with accessory pathway ablation, would include pathways felt to be high-risk, or patients with a high-risk occupations.

The main forms of treatment are drug therapy, radiofrequency (RF) ablation and surgical ablation.

Accessory pathway RF catheter ablation is the first-line treatment for symptomatic WPW syndrome. It has replaced surgical treatment and most drug treatments due to its high success rate and low-risk profile.

Drug treatment may still be appropriate for patients who refuse ablation or as an interim control measure if they are at high risk of complications.

Patients who present with tachyarrhythmic symptoms may require drug therapy to prevent further episodes and while awaiting definitive treatment - this may also be a long-term option for those in whom ablation or surgery are contraindicated, or not wanted.

Digoxin is contra-indicated in patients with WPW syndrome. Most deaths from WPW syndrome have been associated with digoxin use.

Termination of an acute episode25

Narrow-complex AV re-entrant tachycardia is treated in the same way as AVNRT, by blocking AV node conduction. Options include:

Vagal manoeuvres - eg, Valsalva, carotid sinus massage, splashing cold water or iced water on the face.

Intravenous adenosine. Do not use adenosine if atrial fibrillation is suspected, as blocking the AV node can paradoxically increase ventricular rate, resulting in fall in cardiac output (ventricular refractory period after a normally conducted impulse through AV node may be critical in maintaining cardiac output) - cardioversion is more appropriate.

Beta-blockers or calcium-channel blockers can be used as second-line agents with electric cardioversion being reserved for refractory arrhythmias.

Atrial fibrillation can occur after drug administration, particularly adenosine, with a rapid ventricular response. An external cardioverter-defibrillator should be immediately available.

Atrial flutter/fibrillation or wide-complex tachycardia

Atrial flutter/fibrillation causes abnormal QRS complexes and irregular R-R intervals.

Cardioversion may be the best option, as conventional drugs may paradoxically increase the ventricular rate, with risk of ventricular fibrillation.

Patients with atrial fibrillation and rapid ventricular response are often treated with amiodarone or procainamide. Procainamide and cardioversion are accepted treatments for conversion of tachycardia associated with WPW syndrome.

Amiodarone has been used in WPW pattern with atrial fibrillation, but some evidence suggests that it is less effective and has a higher risk of precipitating ventricular. fibrillation. It is not usually a first-line option,

AV node blockers should be avoided in atrial fibrillation and atrial flutter with WPW syndrome. In particular, avoid adenosine, diltiazem, verapamil, and other calcium-channel blockers and beta-blockers. They can exacerbate the syndrome by blocking the heart's normal electrical pathway and facilitating antegrade conduction via the accessory pathway.

Long-term maintenance treatment25

Response to long-term anti-arrhythmic therapy for the prevention of further episodes of tachycardia in patients with WPW syndrome is unpredictable. Some drugs may paradoxically make the reciprocating tachycardia more frequent.

In patients without structural or coronary heart disease, flecainide and propafenone are deemed reasonable.

Dofetilide or sotalol are reasonable options in patients with structural heart disease.

Radiofrequency ablation5

RF ablation is increasingly being used both in common types of arrhythmia and selected asymptomatic patients, with a 95% success rate.

This follows electrophysiological studies to determine the site of the accessory pathway. Rarely, there may be more than one accessory pathway.

This is now first-line management, ahead of open-heart surgical disconnection and cardiac pacing.

Patients who have accessory pathways with short refractory periods do not respond well to drug treatments and are best treated with ablation.

Indications for RF ablation include:

Patients with symptomatic AV re-entrant tachycardia.

Atrial fibrillation or other atrial tachyarrhythmias that have rapid ventricular rates via a bypass tract.

Asymptomatic patients with ventricular pre-excitation, whose livelihood, profession, insurability or mental well-being may be influenced by unpredictable tachyarrhythmias or in whom such tachyarrhythmias would endanger the safety of themselves or others.

Patients with atrial fibrillation and a controlled ventricular response via the bypass tract.

Patients with a family history of sudden cardiac death.

Surgical ablation

Although largely superseded by RF ablation, surgical ablation may still be indicated for patients in whom RF ablation has failed, those who need heart surgery for other reasons and for those patients with multifocal abnormalities requiring surgical ablation (rare).

Complications of Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome

Back to contentsTachyarrhythmia:

WPW syndrome can present with several forms of tachydysrhythmia, depending on the pathway of the aberrant rhythm, including reciprocating tachycardias and atrial fibrillation.

Increased risk of dangerous ventricular arrhythmias due to fast conduction across the bypass tract if they develop atrial flutter or fibrillation.

Digoxin and perhaps other AV nodal blocking agents may accelerate conduction through the bypass tract, causing potentially lethal ventricular arrhythmias or haemodynamic instability during atrial fibrillation.

Occurs rarely.

Risk factors for sudden cardiac death include male gender, age less than 35 years, history of atrial fibrillation or AVRT, multiple accessory pathways, septal location of the accessory pathway and the ability for rapid anterograde conduction of the accessory pathway.

The ten-year risk of sudden cardiac death related to WPW is around 0.2% and is highest below the age of 20.

Sudden cardiac death is unusual without preceding symptoms, but in 0.2% of those with WPW it is the first presentation.

Prognosis

Back to contentsPrognosis is usually very good once treated. Catheter ablation may be curative.

The prognosis depends on the intrinsic electrophysiological properties of the accessory pathway rather than on symptoms.9

Sudden cardiac death is rare but may occur due to arrhythmia or the management of arrhythmia with inappropriate drugs.

In asymptomatic patients, the capacity for antegrade conduction across the accessory pathway often decreases with age. This is probably due to fibrotic changes at the site of insertion of the accessory bypass tract.

Further reading and references

- Scheinman MM; The history of the Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome. Rambam Maimonides Med J. 2012 Jul 31;3(3):e0019. doi: 10.5041/RMMJ.10083. Print 2012 Jul.

- Chhabra L, Goyal A, Benham M. Wolff Parkinson White Syndrome (WPW). StatPearls 2020 last updated August 7 2023. .

- Vatasescu RG, Paja CS, Sus I, et al; Wolf-Parkinson-White Syndrome: Diagnosis, Risk Assessment, and Therapy-An Update. Diagnostics (Basel). 2024 Jan 30;14(3):296. doi: 10.3390/diagnostics14030296.

- Jung HJ, Ju HY, Hyun MC, et al; Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome in young people, from childhood to young adulthood: relationships between age and clinical and electrophysiological findings. Korean J Pediatr. 2011 Dec;54(12):507-11. doi: 10.3345/kjp.2011.54.12.507. Epub 2011 Dec 31.

- 2015 ACC/AHA/HRS guideline for the management of adult patients with supraventricular tachycardia

- Marrakchi S, Kammoun I, Kachboura S; Wolff-Parkinson-white syndrome mimics a conduction disease. Case Rep Med. 2014;2014:789537. doi: 10.1155/2014/789537. Epub 2014 Jul 9.

- ECG Library

- Chadha S, Kulbak G, Yang F, et al; The delta wave in Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome. QJM. 2013 Dec;106(12):1147-8. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcs211. Epub 2012 Oct 29.

- Pappone C, Vicedomini G, Manguso F, et al; Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome in the era of catheter ablation: insights from a registry study of 2169 patients. Circulation. 2014 Sep 2;130(10):811-9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.011154. Epub 2014 Jul 22.

Continue reading below

Article history

The information on this page is written and peer reviewed by qualified clinicians.

Next review due: 17 Sept 2027

17 Sept 2024 | Latest version

Ask, share, connect.

Browse discussions, ask questions, and share experiences across hundreds of health topics.

Feeling unwell?

Assess your symptoms online for free