Ectopic pregnancy

Peer reviewed by Dr Philippa Vincent, MRCGPLast updated by Dr Toni Hazell, MRCGPLast updated 9 Jul 2025

Meets Patient’s editorial guidelines

- DownloadDownload

- Share

- Language

- Discussion

- Audio Version

Medical Professionals

Professional Reference articles are designed for health professionals to use. They are written by UK doctors and based on research evidence, UK and European Guidelines. You may find the Ectopic pregnancy article more useful, or one of our other health articles.

In this article:

Continue reading below

What is an ectopic pregnancy?

An ectopic pregnancy is one that occurs anywhere outside the uterus. By far the commonest place for ectopic pregnancy is the Fallopian tubes.

How common is an ectopic pregnancy? (Epidemiology)12

Back to contentsThe rate of ectopic pregnancy in the UK is 11 per 1,000 pregnancies. Although the mortality from ectopic pregnancies in the UK is decreasing, around 0.2 per 1000 ectopic pregnancies result in maternal death. Two thirds of these maternal deaths are associated with substandard care. Women who are less likely to seek medical help have a worse prognosis. These include recent migrants, asylum seekers, refugees and those who have difficulty reading or speaking English.

Rates of ectopic pregnancy after assisted reproduction are higher than in natural conception, with the risk generally quoted as being around 2%.34

The incidence of heterotopic pregnancy (when both an intrauterine and an ectopic pregnancy are present) varies from 1 in 4,000 women to 1 in 30,000 women in the general population, and possibly up to 1% of IVF pregnancies.5 6

Continue reading below

Where does a ectopic pregnancy occure? (Anatomy)7

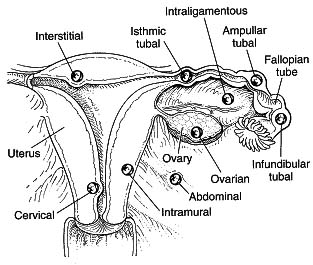

Back to contents95% of ectopic pregnancies occur in the Fallopian tubes. The majority occur in the ampullary or isthmic portions of the Fallopian tubes. About 2-3% occur as interstitial ectopic pregnancies (arising in the part of the tube which goes through the endometrial cavity). The rare remaining locations include cervical, fimbrial, ovarian and peritoneal sites, as well as previous caesarean section scars. There are a few documented cases of viable pregnancy outside the uterus and tubes but, as a general rule, only a intrauterine pregnancy is viable.

Ectopic pregnancy locations

Diagram from The Ectopic Pregnancy Trust, used with permission.

Interstitial, cornual and cervical pregnancy

These terms may be confused, but describe different situations. Cornual pregnancy describes pregnancy in a rudimentary horn of a bicornuate uterus, whilst interstitial pregnancy describes pregnancy in the interstitial rather than extrauterine part of the tube. Interstitial pregnancies represent 2-3% of ectopic pregnancies. Interstitial pregnancy can be misdiagnosed by ultrasound as normal intrauterine pregnancy. It tends to present early and suddenly and often there is catastrophic haemorrhage before the diagnosis is made.

Interstitial pregnancies are rare but dangerous types of ectopic pregnancy. Clinicians should be aware of the difficulties with both clinical and ultrasound diagnosis. The rarest of ectopics (<1%) are implanted within the cervical canal below the level of the internal cervical os. Predisposing factors include prior uterine curettage, induced abortion, Asherman's syndrome, leiomyomata and the presence of an intrauterine contraceptive device (IUD).

Risk factors

Back to contentsOne third of women with ectopic pregnancies do not have risk factors. However, the following increase the risk of ectopic pregnancy:

Assisted reproductive treatments such as in vitro fertilisation (IVF).

History of pelvic infection. Pelvic inflammatory disease may cause complete tubal occlusion or delay the transport of the embryo so that implantation occurs in the tube.

Adhesions from infection and inflammation from endometriosis may play a part.

Previous tubal surgery. Ectopic pregnancy has been reported in tubes that have been divided in a sterilisation operation and where they have been reconstructed to reverse one. A past history of ectopic pregnancy increases the risk.

IUCD use. IUCDs reduce the risk of ectopic pregnancy compared to using no contraception. The risk of ectopic pregnancy with an IUCD or intrauterine system (IUS) in situ is around 1 in 1,000 over five years. However, where an IUCD fails, the risk of a pregnancy being ectopic is very high, with some studies showing half of pregnancies in this situation being ectopic.8

Women becoming pregnant whilst using progestogen-only contraceptive methods may also have an increased risk of ectopic pregnancy (compared to those who become pregnant whilst not using contraception), although a previous history of ectopic pregnancy is not an absolute or a relative contra-indication to use. It is difficult to estimate the magnitude of this effect, if it exists, as many of the available studies are old and look at older pills which relied on thickening the contraceptive mucus, rather than newer ones which are anovulatory. Risks are lowest for depot injection and implants, and of course the absolute risk of an ectopic is much lower for any reliable method of contraception than for no contraception, because the vast majority of both intrauterine and ectopic pregnancies are prevented.9

Continue reading below

Symptoms of ectopic pregnancy (presentation)

Back to contentsBe aware that ectopic pregnancy commonly presents in an atypical way, so consider the possibility in women of reproductive age. Consider the need for a pregnancy test even in women with nonspecific signs.

History10

Symptoms and signs of ectopic pregnancy can resemble those of other more common conditions, including urinary tract infections and gastrointestinal conditions.

The most common symptoms are:

Abdominal pain.

Pelvic pain.

Amenorrhoea or missed period.

Vaginal bleeding (with or without clots).

Other symptoms may include:

Dizziness, fainting or syncope.

Breast tenderness.

Shoulder tip pain.

Urinary symptoms.

Passage of tissue.

Rectal pain or pressure on defecation.

Gastrointestinal symptoms such as diarrhoea and/or vomiting.

There may be a history of a previous ectopic pregnancy. After one ectopic pregnancy the chance of another is much increased.

If the ectopic pregnancy has ruptured, bleeding is profuse and there may be features of hypovolaemic shock, including feeling dizzy on standing. Most bleeding will be into the pelvis and so vaginal bleeding may be minimal and misleading.

Examination

Common signs:

Pelvic or abdominal tenderness.

Adnexal tenderness.

Other possible signs:

Rebound tenderness.

Cervical tenderness.

Pallor.

Abdominal distension.

Enlarged uterus.

Tachycardia and/or hypotension.

Shock or collapse.

NB: there is thought to be a possible increased risk of rupture of an ectopic pregnancy following palpation, so internal examination in primary care would not normally be performed if ectopic pregnancy is suspected, particularly where there is early access to ultrasound.

Women with a positive pregnancy test and any of the following need to be referred to hospital for urgent assessment via the early pregnancy assessment service or on-call gynaecologist out of hours:

Pain and abdominal tenderness.

Pelvic tenderness.

Cervical motion tenderness.

Vaginal bleeding.

Differential diagnosis

Back to contentsIn threatened miscarriage vaginal bleeding is the predominant feature and pain may come later as the cervix dilates. In ectopic pregnancy, pain usually comes first and if vaginal bleeding occurs it is of much less significance.

The differential diagnosis is also as for left iliac fossa pain or right iliac fossa pain.

Diagnosing ectopic pregnancy (investigations)10

Back to contentsA pregnancy test should be performed on all women of childbearing age presenting with lower abdominal pain where pregnancy is even the remotest possibility.

Every aspect of the investigation of a possible ectopic pregnancy should be carried out in an early pregnancy unit (EPAU) - it is not appropriate for any of this, including carrying out or chasing the results of blood tests, to be delegated to primary care.

The most accurate method to detect a tubal pregnancy is transvaginal ultrasound.

This can identify the location of the pregnancy and also whether there is a fetal pole and heartbeat. Ectopic pregnancies are often not positively seen on a scan; it is an empty uterus with a positive pregnancy test which is being looked for; this is known as a pregnancy of unknown location.

Human chorionic gonadotrophin (hCG) levels are performed in women with pregnancy of unknown location who are clinically stable. In a woman with pregnancy of unknown location, however, clinical symptoms are of more significance than hCG levels.

hCG levels are taken 48 hours apart. A change in concentration between 50% decline and 63% rise inclusive over 48 hours is suspicious and should prompt further review.

Treatment of ectopic pregnancy10

Back to contentsAdmit as an emergency if ectopic pregnancy is considered a possibility.

Anti-D rhesus prophylaxis should be given (at a dose of 250 IU) to all rhesus-negative women who have a surgical procedure to manage an ectopic pregnancy. Women who receive medical treatment for their ectopic pregnancy do not need to receive it.

All women should be given written information which is tailored to their care. They should also be given a 24-hour contact telephone number to use if their symptoms worsen or new symptoms develop.

Early pregnancy assessment units should accept self-referrals from women with a history of ectopic pregnancy.

Conservative management may be appropriate if the levels of hCG are falling and the patient is clinically well. Repeat hCG levels are performed in these cases.

It is not possible to move an ectopic pregnancy into the uterus, despite attempts in some areas to legislate for an attempt at this to be mandatory.1112

Medical treatment

Single-dose methotrexate can be used, although its efficacy may be less with higher hCG levels. Re-injection may be required and some studies have cast doubt on whether its efficacy is significantly more than expectant management.13

Medical management in the form of systemic methotrexate is offered first-line to those women who are able to return for follow-up and who have the following:

No significant pain.

Unruptured ectopic pregnancy with an adnexal mass <35 mm and no visible heartbeat.

No intrauterine pregnancy seen on ultrasound scan.

Serum hCG <1500 IU/L.

Over 75% of patients will complain of abdominal pain 2-3 days after administration of methotrexate.14

Other side-effects include nausea, vomiting and reversible impaired liver function.

Women should have blood taken for LFTs and to ensure hCG levels are dropping.

Contraception should be used for 3-6 months, as methotrexate is teratogenic.

Clear instruction must be given about the need for follow-up and the ability to return to the ward if there are problems.

Surgical treatment

Surgery should be offered to those women who cannot return for follow-up after methotrexate or to those who have any of the following:

Significant pain.

Adnexal mass ≥35 mm.

Fetal heartbeat visible on scan.

Serum hCG level ≥5000 IU/L.

A laparoscopic approach is preferable. A salpingectomy should be performed, unless the woman has other risk factors for infertility, in which case a salpingotomy should be undertaken.

Complications of ectopic pregnancy7

Back to contentsEctopic pregnancy would ideally be diagnosed before the woman's condition has deteriorated, resulting in ectopic pregnancy being less likely to be life-threatening disease, but this is not always possible.

Failure to make the prompt and correct diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy can result in tubal or uterine rupture (depending on the location of the pregnancy), which in turn can lead to massive haemorrhage, shock, disseminated intravascular coagulopathy (DIC), and even death.

Complications of surgery include bleeding, infection, and damage to surrounding organs, such as the bowel, bladder and ureters and to the major vessels nearby.

Prognosis

Back to contentsWith accurate determination of very low hCG concentrations and ultrasound, >85% of women are now diagnosed before tubal rupture, which has led to medical therapy and laparoscopic surgery with tubal preservation and the potential for future fertility.15

The risk of another ectopic pregnancy is about 10-20%.

The chance of subsequent intrauterine pregnancy is about 64-76%.1

Further reading and references

- Stabile G, Mangino FP, Romano F, et al; Ectopic Cervical Pregnancy: Treatment Route. Medicina (Kaunas). 2020 Jun 12;56(6). pii: medicina56060293. doi: 10.3390/medicina56060293.

- Szadok P, Kubiaczyk F, Bajorek A, et al; Ovarian ectopic pregnancy. Ginekol Pol. 2019;90(12):728. doi: 10.5603/GP.2019.0125.

- Cali G, Timor-Tritsch IE, Palacios-Jaraquemada J, et al; Outcome of Cesarean scar pregnancy managed expectantly: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Feb;51(2):169-175. doi: 10.1002/uog.17568.

- Ectopic pregnancy; NICE CKS, February 2023 (UK access only)

- Saving Lives, Improving Mothers’ Care; MBRRACE Oct 2024

- Anzhel S, Makinen S, Tinkanen H, et al; Top-quality embryo transfer is associated with lower odds of ectopic pregnancy. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2022 Jul;101(7):779-786. doi: 10.1111/aogs.14375. Epub 2022 May 11.

- Hu Z, Li D, Chen Q, et al; Differences in Ectopic Pregnancy Rates between Fresh and Frozen Embryo Transfer after In Vitro Fertilization: A Large Retrospective Study. J Clin Med. 2022 Jun 13;11(12):3386. doi: 10.3390/jcm11123386.

- Maleki A, Khalid N, Rajesh Patel C, et al; The rising incidence of heterotopic pregnancy: Current perspectives and associations with in-vitro fertilization. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2021 Nov;266:138-144. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2021.09.031. Epub 2021 Oct 4.

- Kajdy A, Muzyka-Placzynska K, Filipecka-Tyczka D, et al; A unique case of diagnosis of a heterotopic pregnancy at 26 weeks - case report and literature review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2021 Jan 18;21(1):61. doi: 10.1186/s12884-020-03465-y.

- Mullany K, Minneci M, Monjazeb R, et al; Overview of ectopic pregnancy diagnosis, management, and innovation. Womens Health (Lond). 2023 Jan-Dec;19:17455057231160349. doi: 10.1177/17455057231160349.

- Intrauterine Contraception; Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare Clinical Effectiveness Unit (March 2023 - last updated July 2023)

- Progestogen-only Pills; Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare (August 2022, amended November 2022)

- Ectopic pregnancy and miscarriage: diagnosis and initial management; NICE Guidance (last updated August 2023)

- Thomas C, Donovan GK, Fernandez MA, et al; Efforts to transfer ectopic embryos to the uterine cavity: A systematic review. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2023 Aug;49(8):1991-1999. doi: 10.1111/jog.15678. Epub 2023 May 16.

- The myth of ectopic pregnancy transplantation; BMJ 2019

- Solangon SA, Van Wely M, Van Mello N, et al; Methotrexate vs expectant management for treatment of tubal ectopic pregnancy: An individual participant data meta-analysis. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2023 Sep;102(9):1159-1175. doi: 10.1111/aogs.14617. Epub 2023 Jun 22.

- Diagnosis and management of ectopic pregnancy; Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Green Top Guideline No 21. November 2016

- Marion LL, Meeks GR; Ectopic pregnancy: History, incidence, epidemiology, and risk factors. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2012 Jun;55(2):376-86. doi: 10.1097/GRF.0b013e3182516d7b.

Continue reading below

Article history

The information on this page is written and peer reviewed by qualified clinicians.

Next review due: 8 Jul 2028

9 Jul 2025 | Latest version

Ask, share, connect.

Browse discussions, ask questions, and share experiences across hundreds of health topics.

Feeling unwell?

Assess your symptoms online for free