Retinal vein occlusions

Peer reviewed by Dr Doug McKechnie, MRCGPLast updated by Dr Philippa Vincent, MRCGPLast updated 22 Dec 2024

Meets Patient’s editorial guidelines

- DownloadDownload

- Share

- Language

- Discussion

Medical Professionals

Professional Reference articles are designed for health professionals to use. They are written by UK doctors and based on research evidence, UK and European Guidelines. You may find the Retinal vein occlusion article more useful, or one of our other health articles.

In this article:

Continue reading below

What are retinal vein occlusions?

Retinal vein occlusions (RVOs) are the second most common type of retinal vascular disorder after diabetic retinal disease.1 They can occur at almost any age (although typically occur in middle to later years - most in those aged over 65 years) and their severity ranges from asymptomatic to a painful eye with severe visual impairment.

Retinal vein occlusion is one of the most common causes of sudden painless unilateral loss of vision. Loss of vision is usually secondary to macular oedema. Occlusion may occur in the central retinal vein or branch retinal vein.2

Pathophysiology

Central retinal vein occlusion (CRVO) can be divided into ischaemic CRVO and non-ischaemic CRVO. Non-ischaemic CRVO is more common, accounting for 75% of cases.34

Occlusion of the retinal venous system by thrombus formation is the most common cause but other causes include disease of the vein wall and external compression of the vein. Retinal arteries and arterioles and their corresponding veins share a common adventitial sheath. It is thought that the thickening of the arteriole compresses the vein, eventually causing occlusion.

A backlog of stagnated blood combined with associated hypoxia results in extravasation of blood constituents, causing further stagnation and so on, resulting in the creation of a vicious circle of events. Ischaemic damage to the retina stimulates increased production of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) which, in turn, may lead to neovascularisation - a process that can result in haemorrhage (as the new vessels are of poor quality) or neovascular glaucoma (the new vessels grow into the aqueous drainage system, so clogging it up). Factors contributing to this pathophysiology include:

Advancing age.

Systemic conditions such as hypertension (found in 64% of patients with RVO), hyperlipidaemia, diabetes, smoking and obesity.

Raised intraocular pressure.

Inflammatory diseases such as sarcoidosis, Behçet's syndrome.

Hyperviscosity states such as myeloma.

There are more unusual associations, including chronic kidney disease, other secondary causes of hypertension and diabetes (eg, Cushing's syndrome), secondary causes of hyperlipidaemia (eg, hypothyroidism), polyarteritis nodosa, granulomatosis with polyangiitis, Goodpasture's syndrome.

Continue reading below

Branch retinal vein occlusion

Branch retinal vein occlusions (BRVOs) are three times more common than central retinal vein occlusions (CRVOs). There are various subclassifications of this depending on whether a major branch, a minor macular branch or a peripheral branch is affected. Each carries its own prognosis. A hemiretinal vein occlusion refers to an occlusion that is proximal enough to affect half of the retinal drainage (ie the superior or inferior portion) as opposed to the smaller portion affected by a BRVO.

Presentation

This largely depends on the amount of compromise to macular drainage. The most common presentation is of unilateral, painless blurred vision, metamorphopsia (image distortion) ± a field defect (usually altitudinal). Peripheral occlusions may be asymptomatic. Visual acuity depends on the degree of macular involvement. Fundoscopy will reveal vascular dilatation and tortuosity of the affected vessels, with associated haemorrhages in that area only (look for an arc of haemorrhages, like a trail left behind a cartoon image of a shooting star).

Management

Urgent referral to an on-call ophthalmologist.

Management depends on the area and degree of occlusion.

Some patients benefit from panretinal photocoagulation (PRP) laser treatment if they develop macular oedema (where visual acuity is ≤6/12 and there is no spontaneous improvement by 3-6 months) or neovascularisation.

Triamcinolone is no longer recommended for the treatment of macular oedema in BRVO.

Dexamethasone biodegradable implants are licensed for treatment of macular oedema secondary to BRVO.

Use of the anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (anti-VEGF) ranibizumab has been shown to have sustained benefit for macular oedema resulting from BRVO. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommends that it should be used only if treatment with laser photocoagulation has not been beneficial, or when laser photocoagulation is not suitable because of the extent of macular haemorrhage.5

Complications

These are similar to those of CRVO. New vessels tend to occur only when at least one quadrant of the retina is affected, and appear about six months after the original occlusion. The rate of complication for hemiretinal vein occlusions is greater than that of BRVO but less than that of CRVO.

Outcome

The outcome is reasonably good depending on the number of collateral veins that develop. 50% of patients return to a visual acuity of 6/12 or better. Over half will develop macular oedema and about one in five may develop retinal neovascularisation.

Central retinal vein occlusion

CRVO has two broad categories, which may overlap:

The milder form of the disease is non-ischaemic CRVO (accounting for ~75% of CRVOs). This may resolve fully with good visual outcome or progress to the ischaemic type.

The severe form of the disease is ischaemic CRVO. Patients may be left with neovascular glaucoma and a painful eye with severe visual impairment.

In some cases, the cut-off between the two can be arbitrarily based on angiographic findings but it is a useful predictor of outcome and complication development.

How common is central retinal vein occlusion? (Epidemiology)

This is a common condition. UK figures are not available. The prevalence of central vein retinal occlusion has been reported to be 0.8 per 1000 people in the developed world.3 The incidence increases with age. There is an equal sex distribution.

Presentation

The patient (usually aged >50) frequently presents with sudden unilateral painless loss of vision or blurred vision, often starting on waking.2

Non-ischaemic - mild or absent afferent pupillary defect. There are widespread dot-blot and flame haemorrhages throughout the fundus and some disc oedema.

Ischaemic - severe visual impairment with a marked afferent pupillary defect. The fundus looks similar to the non-ischaemic picture but disc oedema is more severe. Haemorrhages scattered throughout the fundus in typical blood-storm pattern with cotton wool spots (sparse scattered haemorrhages with less complete blockage). There may occasionally be an associated retinal detachment.4

Branch retinal vein occlusion

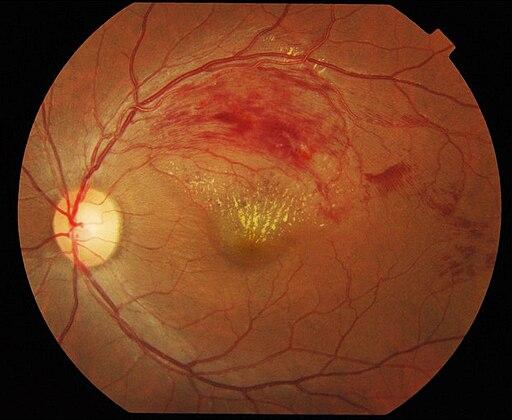

Ku C Yong, Tan A Kah, Yeap T Ghee, Lim C Siang and Mae-Lynn C Bastion, Department of Ophthalmology, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia Medical Centre (UKMMC) and Universiti Malaysia Sarawak (UNIMAS), Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia., CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Differential diagnosis

Diabetic retinopathy.

Other causes of sudden unilateral loss of vision - eg, retinal detachment, retinal artery occlusion.

Other causes of macular oedema.

Management

Currently, there are no proven treatment options available so management has the twofold aim of identifying/managing modifiable risk factors and recognising/treating complications. Where there is development of severe visual impairment due to a secondary complication (eg, neovascular glaucoma), the management aim is to keep the eye pain-free.

Urgent referral to the on-call ophthalmologist.

Investigations will include:3

Blood pressure.

Blood tests including ESR, FBC, lipid profile, blood glucose, renal function and thyroid function.

ECG (looking for LVH).

Patients under the age of 50 or with bilateral RVO or a family history should also be offered:3

Chest x-ray (looking for sarcoidosis or tuberculosis).

CRP, auto-antibodies, serum ACE levels, syphilis screen, serum homocysteine levels.

Thrombophilia screen.

Carotid duplex imaging.

The ophthalmologist will seek certain features that distinguish ischaemic from non-ischaemic CRVO. The former will be observed every 2 to 3 months ± treated with laser (panretinal photocoagulation) should any neovascularisation - particularly around the iris - occur.

Reduction of intraocular pressure is needed if this is elevated.

Intravitreal anti-VEGF agents:

In combination with use of laser panretinal photocoagulation (PRP), should be used when iris new vessels or angle new vessels are visible.

PRP results in dramatic regression of the new vessels. The effect is short-lived and new vessels recur commonly, so repeated treatment (typically every six weeks) with these agents (and PRP) may be required.

Intravitreal aflibercept injection is recommended as an option for treating visual impairment caused by macular oedema secondary to CRVO.6

Intravitreal triamcinolone has been evaluated but its beneficial effects in CRVO are short-lived and it is rarely offered as a treatment currently.

Intravitreal steroids have also been studied with regard to treating post-CRVO macular oedema. Currently, the response has been found to be positive but limited temporally and there are a number of complicating side-effects.7

Laser-induced chorioretinal venous anastomosis (L-CRA) has been used as a treatment for non-ischaemic CRVO. Improvements in laser technology have led to higher success rates in L-CRA creation and a reduction in complications.8

Any underlying modifiable risk factors will need to be identified and addressed.

Complications

Retinal neovascularisation (and secondary glaucoma or vitreous haemorrhage - the '90-day glaucoma').

Macular oedema ± lamellar or full-thickness macular hole.

Permanent macular degeneration or 'cellophane maculopathy'.

Outcome

The prognosis in central retinal vein occlusion is best in patients under the age of 50. In patients over 50, one third improve, one third stay the same and one third deteriorate.3

In non-ischaemic retinal vein occlusion, about 50% return to baseline or near-baseline visual acuity. Chronic macular oedema is the main cause of ongoing visual loss. The prognosis is usually linked to the initial visual acuity on diagnosis. Patients with initial visual acuity of 20:60 or better, normally stay the same. Patients with an initial visual acuity of 20:200 or worse, also usually stay the same and rarely improve, Patients with an initial visual acuity between these have a more variable clinical course with some improving, some worsening and some staying the same.3

In ischaemic retinal vein occlusion, the prognosis is more variable. 50% will develop glaucoma in the first 2-4 months. Less than 5% will re-vascularise.3

There is no risk of increased long-term mortality (in contrast to retinal artery occlusion). However, there is a risk of developing CRVO in the fellow eye.

Continue reading below

Investigations

In the eye clinic, further evaluation includes:

Measurement of intraocular pressure.

Fluorescein angiography is the investigation of choice in CRVO. It evaluates retinal capillary non-perfusion, neovascularisation and macular oedema. It is not often necessary in BRVO.

Optical coherence tomography angiograph (OCTA). This is non-invasive, transpupillary imaging. It measures the retina and can detect macular oedema that fluorescein angiography has missed because of blockage from haemorrhage.9

Non-ophthalmological management of retinal vein occlusions

The ophthalmology team is primarily concerned with the diagnosis of RVO and the management of the ocular complications. Baseline investigations should be carried out by the ophthalmology team at the time of diagnosis.

It is also their responsibility to impart this information effectively to the patient's GP, as underlying risk factors need to be assessed and addressed urgently. Rarer causes (such as those encountered in younger patients) need managing by relevant specialists. Initiation of medical management should occur within two months of diagnosis.

Risk factors have been identified in 'Pathophysiology', above. The principal area of investigation and management will be the cardiovascular risk factors. See the separate Prevention of cardiovascular disease article.

Issues which may arise in the context of general practice

Hormone replacement therapy (HRT) - historically, HRT was contra-indicated and discontinued in women experiencing an RVO. However, more recent studies have shown that continued use does not appear to be associated with a higher rate of recurrence. In addition, transdermal oestrogen is not thought to increase any thrombotic event risk. Previously, restarting HRT was advised on a case-by-case basis but starting HRT de novo was not advised. With the increasing use of TD oestrogen this may be changing and advice should be sought on a case-by-case basis.

The management of younger patients - although the visual outcome in this group of patients appears to be better, RVOs are associated with underlying systemic conditions which should be managed appropriately. In females, the most common association is with the oral contraceptive pill. Thus, an RVO is a contra-indication for this. Sometimes, no underlying cause can be found despite extensive investigations - this group presents a management problem and is likely to be under ophthalmological observation for a much longer period of time.

Further reading and references

- Aflibercept for treating visual impairment caused by macular oedema after branch retinal vein occlusion; NICE Technology appraisal guidance, September 2016

- Blair K, Czyz CN; Central Retinal Vein Occlusion.

- Central Retinal Vein Occlusion; Columbia Ophthalmology

- Esmaili DD, Boyer DS; Recent advances in understanding and managing retinal vein occlusions. F1000Res. 2018 Apr 16;7:467. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.12886.1. eCollection 2018.

- Blair K, Czyz CN; Central Retinal Vein Occlusion. StatPearls 2020.

- Blair K, Czyz CN; Central Retinal Vein Occlusion.

- Central Retinal Vein Occlusion; Columbia Ophthalmology

- Ranibizumab for the treatment of diabetic macular oedema; NICE Technology Appraisal Guidance, February 2013 - last updated October 2023

- Aflibercept for treating visual impairment caused by macular oedema secondary to central retinal vein occlusion, NICE Technology appraisal guidance, February 2014

- Gewaily D, Greenberg PB; Intravitreal steroids versus observation for macular edema secondary to central retinal vein occlusion. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2009, Issue 1. Art. No.: CD007324. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD007324.pub2

- McAllister IL; Chorioretinal Anastomosis for Central Retinal Vein Occlusion: A Review of Its Development, Technique, Complications, and Role in Management. Asia Pac J Ophthalmol (Phila). 2020 May-Jun;9(3):239-249. doi: 10.1097/APO.0000000000000286.

- Tsai G, Banaee T, Conti FF, et al; Optical Coherence Tomography Angiography in Eyes with Retinal Vein Occlusion. J Ophthalmic Vis Res. 2018 Jul-Sep;13(3):315-332. doi: 10.4103/jovr.jovr_264_17.

Continue reading below

Article history

The information on this page is written and peer reviewed by qualified clinicians.

Next review due: 21 Dec 2027

22 Dec 2024 | Latest version

Ask, share, connect.

Browse discussions, ask questions, and share experiences across hundreds of health topics.

Feeling unwell?

Assess your symptoms online for free