Retinal detachment

Peer reviewed by Dr Doug McKechnie, MRCGPLast updated by Dr Colin Tidy, MRCGPLast updated 18 Dec 2024

Meets Patient’s editorial guidelines

- DownloadDownload

- Share

- Language

- Discussion

The retina is a structure at the back of the eye which is essential for sight. When two layers of tissue in the retina become separated, it is known as a retinal tear or detachment. It is a very serious eye condition and can cause severe visual impairment if it is not treated promptly. However, with rapid diagnosis and treatment, which is usually surgery, the outlook (prognosis) may be very good for some types of retinal detachment.

In this article:

Video picks for Eye injuries

Continue reading below

What is retinal detachment?

Retinal detachment (RD) is when the tissue at the back of the eye (retina) pulls away from its regular position, causing vision loss. If the retina detaches, it will stop working and affect your vision.

A retinal detachment can be repaired with surgery, but it needs to be detected and treated quickly, or it can cause loss of vision. Retinal detachment is therefore an emergency and needs to be assessed as soon as possible by a hospital eye specialist (ophthalmologist).

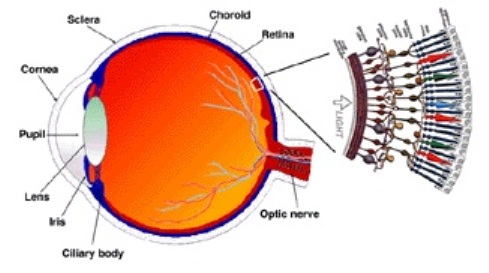

What is the retina?

Light enters the eye and is focused on the retina by the lens. The retina produces a picture which is then sent to the optic nerve which transports the picture to the brain. If the retina is damaged or not in its correct position, a clear picture cannot be produced.

Retinal anatomy

© د.مصطفى الجزار, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

By د.مصطفى الجزار (Own work) CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The retina is made up of two main layers. There is an inner layer of 'seeing cells' called rods and cones. These cells react to light and send electrical signals via the optic nerve to the brain. The cones help us to see in the daylight, and form colour vision. Rods help us to see in the dark. The outer layer - the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) - is a layer of cells behind the rods and cones. The RPE helps to nourish and support the rods and cones. It acts like a filter, keeping harmful substances away from the sensitive cells.

The macula is the small area of the retina where your central vision is formed. It is about 5 mm in diameter. The macula is the most densely packed with rods and cones. In the middle of the macula is an area called the fovea, which only contains cones. The fovea forms your pinpoint central vision.

The tiny blood vessels of the choroid bring oxygen and nutrients to the retina. Bruch's membrane is a thin protective barrier between the choroid and the delicate retina.

When you look at an object, light from the object passes through the cornea, then the lens and then hits the retina at the back of the eye.

Detached retina symptoms

Back to contentsSymptoms of retinal detachment include:

Flashes of light. Initially, you may notice flashing lights in your field of vision. This is noticed in 6 out of 10 people with retinal detachment and is most obvious in dim lighting and in side (peripheral) vision. It is thought to be caused by the retina being tugged and can be a warning sign.

Floaters. Floaters typically appear as one or more black moving dots in your vision. Sometimes they appear like cobwebs or curved shapes. The presence of floaters does not necessarily mean that you have RD, as floaters are very common. However, if you have any new floaters, a sudden increase in size and number of floaters, and floaters and flashes together, then contact your doctor urgently.

Vision loss. You may notice shadowing in your peripheral vision, cloudy vision or loss of vision like a curtain coming over your eye. This is a sign of the retina actually detaching and you should seek medical help at once.

No symptoms. Early tears or detachments in the retina cause no symptoms and are detected on routine eye checks.

It is very important to see your doctor or optician immediately if you have any of the symptoms above. If it is RD, the quicker it is treated, the better the outcome.

Are there any complications?

If retinal detachment is not treated promptly, it can lead to severe visual impairment in the affected eye. Occasionally the second eye is also affected.

Continue reading below

Retinal detachment treatment

Back to contentsTreatment is usually needed urgently if there are any signs of retinal detachment. The sooner retinal detachment is treated, the better the outcome. In particular, it is best to fix an RD before it extends to affect the macula - the most important, central, seeing part of the retina. The aim of treatment is to persuade the retina and the RPE to stick back together again, whilst sealing any tears to stop them from spreading and worsening. There are several procedures that can be used to achieve these aims. More than one procedure may be used for the same person, depending on circumstances. The procedure or procedures that are done depend on the size, exact site, duration, severity and type of RD.

The procedures that may be considered for retinal detachment surgery include the following:

Laser or freezing treatment. A retinal break can be fixed with a fine laser or by freezing (cryotherapy) of the break. This may be sufficient if no fluid has started to seep under the tear. Treatment is in a hospital clinic using local anaesthetic drops. It seals the break, rather like 'welding' the layers back together.

Scleral buckling. This is an operation done under general or local anaesthesia. A small piece of silicone is stitched next to the outer wall of the eye (the sclera) over the site of the retinal tear. This pushes the sclera (and therefore the retina) inwards against the detached segment. This procedure is called scleral buckling because the sclera is 'buckled' inwards by the silicone. In some cases a band of silicone may be placed all around the outside of the eye, like a belt. During the operation, some of the fluid that has built up behind the retina may be drained away. This can help the retina to re-attach better. However, if the fluid is not drained away at the time of the operation, it will gradually become absorbed back into the bloodstream. Once the silicone or plastic buckle is in place, a gas bubble may be injected into the vitreous cavity to keep the retina flat up against the RPE so that it can re-attach. The gas bubble gradually disperses over a few weeks. The silicone buckle is usually left on the eye permanently. Someone looking at you cannot see the buckle, as it is stitched to the sclera somewhere towards the back of the eye. Scleral buckling may be done in addition to laser or freezing treatment to fix a retinal break.

Pneumatic retinopexy

Pneumatic retinopexy. This may be done under local anaesthetic. The eye specialist injects a gas bubble into the vitreous cavity of the eye. The bubble pushes the detached part of the retina flat back up against the RPE. This then allows the retina and the RPE to re-attach permanently. The gas bubble gradually disperses and goes over a few weeks. For this treatment to work, you must keep your head in a set position for most of the time for a few weeks, to encourage the bubble to sit in the right spot. Some people find this very uncomfortable and so pneumatic retinopexy may not be suitable for everyone. It is most commonly done for RDs in the upper part of the retina. For this, the position needed is for your head to be down and forward to allow the bubble to rise and push gently over where the RD is situated. This head positioning can be tedious and hard work for the few weeks that it may be needed until the retina is firmly attached back to its proper place. Pneumatic retinopexy may be done in addition to laser or freezing treatment to fix a retinal break.

Vitrectomy. This is done under general or local anaesthesia. The gel-like substance called the vitreous humour is removed. The space left is then filled with a gas liquid or oil which pushes the retina back into place. The gas eventually disperses but is replaced by natural body fluid made in the eye. A scleral buckle may be applied at the same time as a vitrectomy is performed. After any of these treatments you will usually be given antibiotic and steroid drops to prevent infection and soothe inflammation. You may also need drops to lower the pressure in your eye and to relax the muscles of the iris.

Following surgery things to avoid with retinal detachment include sudden head movements and certain activities, such as heavy lifting, strenuous exercise, flying, being at high altitudes and scuba diving, which may increase the risk of eye injury.

After any treatment, if you experience significant pain or deterioration in your vision, you must inform your doctor immediately.

Retinal detachment causes

Back to contentsWhat is the most common cause of retinal detachment?

The most common cause of the retinal break is a posterior vitreous detachment. This is a very common condition of older people which occurs when the vitreous gel (the jelly-like substance filling the globe of the eye) shrinks and pulls away from the retina. A high proportion of people aged over 60 years have a vitreous detachment. However, in most cases the detachment will not damage the retina. Vitreous detachment leads to retinal tear in 10-15% of cases.

There are three different reasons for retinal detachment:

Rhegmatogenous retinal detachment. In this type of retinal detachment, a hole or break develops in the retina. This can allow fluid from the jelly-like centre of the eye (the vitreous humour) to creep in between the two layers of the retina (the light-sensitive cell layer and the RPE). This causes these two layers to separate (detach). This is the most common type of detachment.

Traction retinal detachment. Inflammation, eye surgery, eye infection or eye trauma can cause scar tissue (fibrous tissue) to form in the eye between the vitreous and the rods and cones. It can tug on the rods and cones, causing them to lift off the RPE. This is seen as a complication of inflammatory conditions such as uveitis.

Exudative retinal detachment. In this type of RD, fluid seeps out of blood vessels in the retina into the space between the retina and the RPE. This can occur as an uncommon complication of various conditions such as very severe high blood pressure, certain cancers and certain types of uveitis. Exudative RD generally resolves with successful treatment of the underlying disease, with very good recovery.

Retinal detachment

Risk factors for retinal detachment

Retinal detachment is more likely with the following:

Aged over 50.

Previous retinal detachment.

Family history of retinal detachment.

Near-sightedness (myopia). The greater the myopia, the greater the risk.

Previous eye surgery, such as cataract removal.

Previous severe eye injury.

Retinal detachment is becoming increasingly common in children, due to eye injury from contact sports and leisure activities such as paintball.

Continue reading below

How long before retinal detachment causes blindness?

Back to contentsThere is no definite answer for how long it takes for a retinal detachment to cause blindness. However, blindness may occur very quickly so if you think you may be experiencing symptoms of retinal detachment, you need to contact a doctor or get to your nearest eye hospital immediately. If the retinal detachment isn’t treated as soon as possible, more of the retina can detach, which increases the risk of permanent vision loss or blindness.

Retinal detachment diagnosis

Back to contentsRD is diagnosed by an eye doctor (ophthalmologist) using a special lamp to look into the back of your eye (retinal detachment fundoscopy). The specialist can also check your vision.

If your GP suspects RD from your symptoms or their examination, you should be referred immediately to an eye specialist who can confirm the diagnosis and arrange treatment. The specialist will need to put some drops into your eye to open wide (dilate) your pupil so they can see the retina properly. These drops will cause a temporary blurring of your vision, which wears off over a few hours.

There are usually no other tests required to diagnose RD.

If the doctor cannot see into your eye properly - for example, if you have a clouding of the lens in your eye (a cataract) - the following may be done to view your retina:

An ultrasound scan of your eye; or

An eye scan called optical coherence tomography.

After any treatment, if you experience significant pain or deterioration in your vision, you must inform your doctor immediately.

What is the outlook (prognosis)?

Back to contentsThis depends on several factors:

The length of time that the retina has been detached.

The cause of the retinal detachment.

The amount of the retina that is involved.

Whether the macula is involved.

If the RD does not involve the macula and is treated promptly, life after retinal detachment surgery usually means a good recovery with restoration of most of your vision is expected. It may take some weeks for vision to improve and glasses may be required permanently to aid vision.

If the macula has detached then the chances of treatment restoring your vision are much lower. Around 4 out of 10 people with macular detachment will recover useful vision. They tend to be patients in whom the macula was detached for a shorter period and they tend to be younger patients. Other patients may be left with some functional vision. However, for some, macular detachment will lead to severe visual impairment in the affected eye.

Having had RD in one eye increases the risk of it happening in the other eye. It can also occasionally recur in the first eye. For this reason you should be alert to any new symptoms and attend regular eye checks well into the future.

Dr Mary Lowth is an author or the original author of this leaflet.

Patient picks for Eye injuries

Eye health

Corneal injury and foreign bodies

Minor scratches or abrasions to the cornea are common. They can be extremely sore but usually heal in 24-48 hours. A course of antibiotic eye drops or ointment is commonly prescribed to prevent an eye infection from developing. More serious injuries to the eye may occur from sharp objects and from small flying particles hitting the eye at high speed. Serious injury can also result from chemical burns. Always see a doctor for a proper eye examination if you suspect that your eye has been injured from a small flying particle, or from a chemical.

by Dr Mary Elisabeth Lowth, FRCGP

Eye health

Subconjunctival haemorrhage

A subconjunctival haemorrhage is one common cause of a red eye. It is caused by a small bleed behind the covering of the eye. It can look alarming but it usually causes no symptoms and is usually harmless. The redness usually clears within two weeks.

by Dr Toni Hazell, MRCGP

Further reading and references

- Retinal detachment; NICE CKS, August 2024 (UK access only)

- Kwok JM, Yu CW, Christakis PG; Retinal detachment. CMAJ. 2020 Mar 23;192(12):E312. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.191337.

- Steel D; Retinal detachment. BMJ Clin Evid. 2014 Mar 3;2014:0710.

- Radeck V, Schindler F, Helbig H, et al; Characteristics of Bilateral Retinal Detachment. Ophthalmologica. 2023;246(2):99-106. doi: 10.1159/000527625. Epub 2022 Oct 25.

Continue reading below

Article history

The information on this page is written and peer reviewed by qualified clinicians.

Next review due: 17 Dec 2027

18 Dec 2024 | Latest version

Ask, share, connect.

Browse discussions, ask questions, and share experiences across hundreds of health topics.

Feeling unwell?

Assess your symptoms online for free

Sign up to the Patient newsletter

Your weekly dose of clear, trustworthy health advice - written to help you feel informed, confident and in control.

By subscribing you accept our Privacy Policy. You can unsubscribe at any time. We never sell your data.