Anaphylactic shock: symptoms, triggers, and what to do

Peer reviewed by Dr Krishna Vakharia, MRCGPAuthored by Amberley DavisOriginally published 19 Jun 2022

Meets Patient’s editorial guidelines

- DownloadDownload

- Share

- Language

- Discussion

- Audio Version

Up to 1 in 5 allergic people live in fear of death from a possible anaphylactic shock - a severe and often sudden allergic reaction that requires emergency medical attention. Thankfully, fatalities are rare, but if you or a loved one has a severe allergy, it's important to know the warning signs and what to do.

In this article:

Video picks for Allergies

Continue reading below

What is anaphylactic shock?

Anaphylactic shock - also known as anaphylaxis - is a severe allergic reaction that often comes on very suddenly and without warning.

According to Anaphylaxis UK1, the reaction "usually begins within minutes and rapidly progresses, but in some cases it can also occur up to 2-3 hours later". The UK charity warns that anaphylaxis is "potentially life-threatening, and always requires an immediate emergency response".

It's important to note that not all allergic reactions are considered to be anaphylaxis. Many people with allergies will never experience a reaction this extreme.

Nonetheless, the possibility of anaphylactic shock can be a great source of stress and anxiety in people's lives. For example, approximately 41% of parents who have children with diagnosed food allergies are thought to have higher stress levels2.

What are the symptoms of anaphylactic shock?

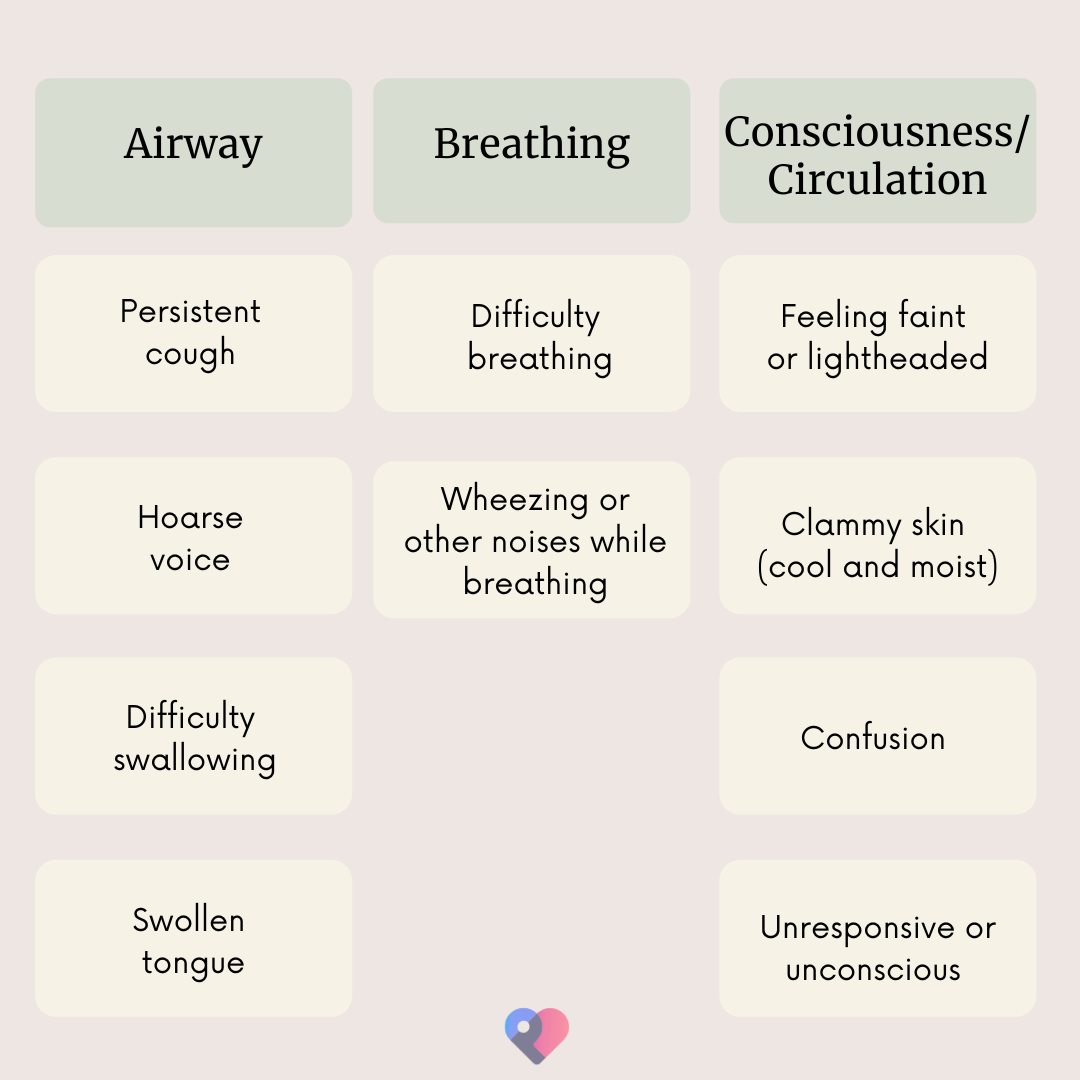

Back to contentsIf you or someone you are with starts having an allergic reaction, look out for the 'ABC symptoms' (Airway, Breathing, Consciousness/Circulation) of an anaphylactic shock3.

Anaphylaxis UK ABC symptoms

These symptoms of anaphylaxis can rapidly become worse as a person's blood pressure drops.

Continue reading below

Can anaphylactic shock kill you?

Back to contentsThis is a life-threatening allergic reaction sometimes resulting in death. Fortunately, this outcome is rare - occurring in just one in a thousand of all cases4. In the UK, this roughly translates to around 20 deaths per year.

Deaths are more likely to occur if adrenaline auto-injectors (AAIs),often known as 'epi-pens', aren't administered in time. This happens more often when people don't carry this prescribed emergency treatment device with them when outside the house.

What causes anaphylactic shock?

Back to contentsAn anaphylactic shock may be triggered when you are exposed to something that you are allergic to (known as an allergen). During an allergic reaction, your immune system attacks this allergen as if it were a harmful substance.

Allergic reactions can range from very mild to severe, and an anaphylactic reaction falls into the latter category. Here, the immune system's overreaction disrupts essential bodily functions which cause symptoms such as difficulty breathing, a swollen tongue, and feeling faint.

The 'shock' part of anaphylactic shock refers to the drop in blood pressure, which reduces the amount of blood delivered to the major organs. This happens when blood vessels leak fluid from the blood into surrounding tissues.

In around 20% of cases, no allergen trigger is identified (called idiopathic anaphylaxis)4. Currently, it's thought that many such reactions will be caused by 'hidden' food allergens that are hard to identify. If you experience idiopathic anaphylaxis, you may be referred to an allergy clinic where a specialist can try various allergy tests to shed light on which ingredients in your diet are the culprits.

What are the most common triggers for anaphylactic shock?

According to Anaphylaxis UK: "Anything can be an allergen, but the most common allergens that may trigger anaphylaxis are food, drugs, insects, or latex."

Food - the 14 major food allergens are nuts, gluten (a protein found in wheat)5, sulphites/sulphur dioxide (used as preservatives in a wide range of foods), celery, crustacean, egg, fish, lupin beans, milk, mustard, mollusc, sesame, and soya.

Drugs - while they tend to be safe for most people, certain medicinal drugs may cause allergic reactions. Common examples include antibiotics (such as penicillin) and painkillers (such aspirin, morphine, and codeine).

An insect sting or bite - some people are highly allergic to the venom injected through some insect bites and stings - for example, wasp or bee stings.

Latex - certain people are allergic to proteins found in latex, a material made from the rubber tree. Products made from latex include balloons, gloves, and condoms.

Continue reading below

How to stop anaphylactic shock

Back to contents1. Administer adrenaline auto-injector

If you believe someone you are with is experiencing anaphylactic shock, the first thing you should do is check if they are carrying an adrenaline auto-injector. If they have been diagnosed as at risk for anaphylaxis, then their doctor will have prescribed this injection device and instructed them to keep it with them at all times6.

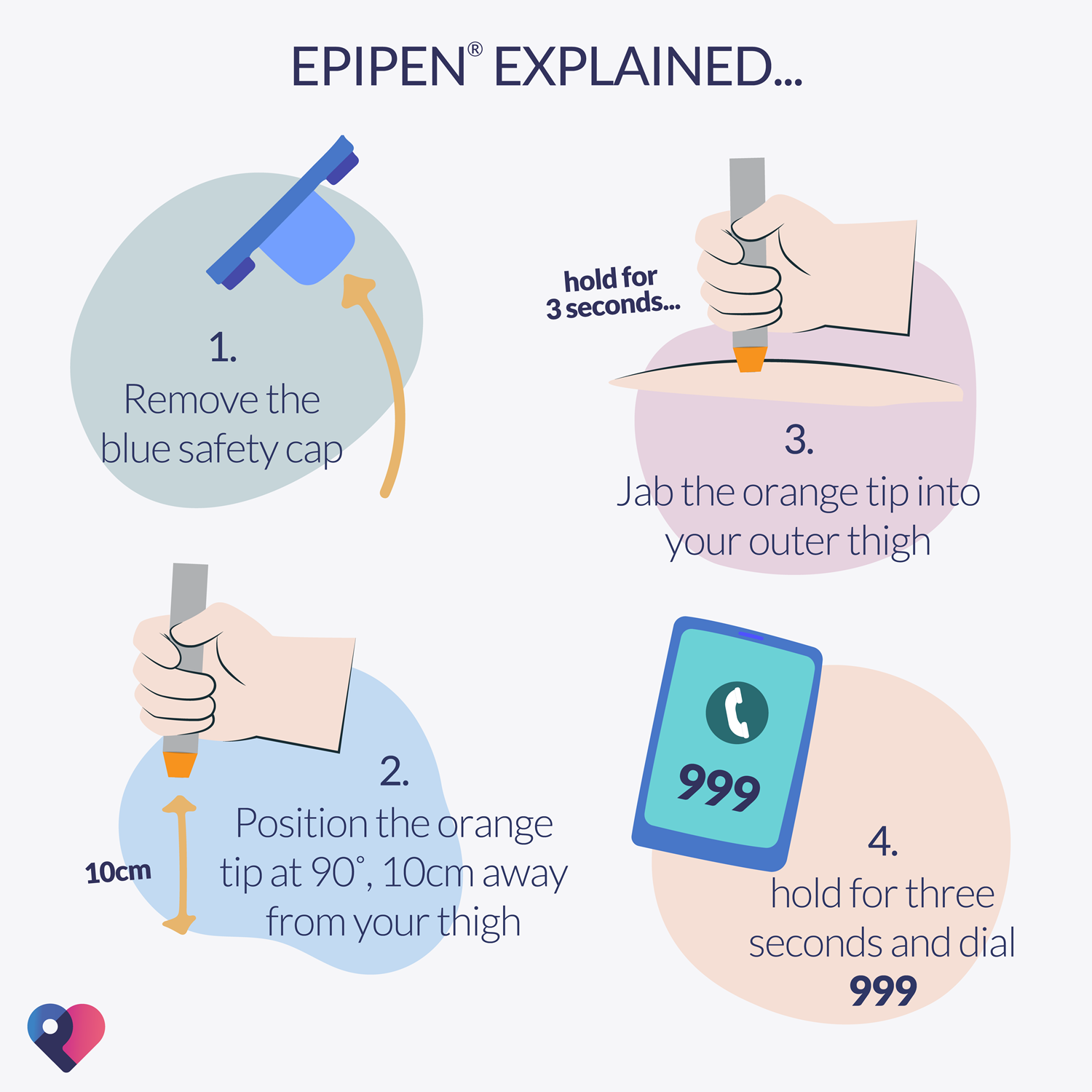

The AAI is loaded with adrenaline (sometimes called epinephrine). A shot of this hormone can quickly open up the airways, reduce swelling, and raise blood pressure. The three main AAIs available in the UK are EpiPen, Jext, and Emerade, and all should be injected into the middle of the outer thigh (upper leg). This can be done through clothing if necessary7.

Figure 1

Use this device as soon as you can - the quicker it's administered, the more effective it can be. If you yourself have been prescribed an AAI, Anaphylaxis UK strongly recommends ordering a trainer device so that you can practise using it. Your doctor will provide training for you and for people who may be required to give you an injection - such as close family or school staff.

2. Call emergency services

Anaphylactic shock is potentially life-threatening, and you must call 999 (if in the UK) and request an ambulance as soon as possible. Hospital treatments depend on the severity of the reaction. They include adrenaline injection, resuscitation, and allergy medicines (such as antihistamines and steroids).

How to prevent anaphylactic shock

Once you've identified the cause of your allergy, you may be able to prevent anaphylaxis by avoiding triggers. This means:

Checking labels and ingredients on food and drinks packets as well as products such as shampoo and toothpaste, even for trace amounts of the allergen.

Informing restaurant staff of your allergies and their severity.

Using insect repellent.

Moving calmly away from insects you're allergic to in order to prevent being stung.

Not walking around barefoot.

Being careful when drinking out of cans - insects are attracted to sugar and may crawl inside and sting you when you take a sip.

If you're allergic to certain medicines, there are usually alternatives a doctor can prescribe instead.

Further reading

Back to contentsPatient picks for Allergies

Allergies, blood and immune system

How to protect your baby against allergies

Allergies can be really distressing for any child but particularly for babies. This is because they don't understand what is happening to them and therefore become distressed. This can be upsetting to watch as a parent. Fortunately, there are things you can do to protect your baby against allergies and ease their symptoms.

by Emily Jane Bashforth

Allergies, blood and immune system

What's the difference between a side effect and a drug allergy?

Many of my patients get confused between side effects or intolerance and allergy. Side effects may settle with time and there may be steps you can take to reduce your chance of having them. But if you have an allergic reaction, you must stop the medicine and not take it again.

by Victoria Raw

Continue reading below

Article history

The information on this page is peer reviewed by qualified clinicians.

19 Jun 2022 | Originally published

Authored by:

Amberley DavisPeer reviewed by

Dr Krishna Vakharia, MRCGP

Ask, share, connect.

Browse discussions, ask questions, and share experiences across hundreds of health topics.

Feeling unwell?

Assess your symptoms online for free

Sign up to the Patient newsletter

Your weekly dose of clear, trustworthy health advice - written to help you feel informed, confident and in control.

By subscribing you accept our Privacy Policy. You can unsubscribe at any time. We never sell your data.