Stevens-Johnson syndrome

Peer reviewed by Dr Laurence KnottLast updated by Dr Colin Tidy, MRCGPLast updated 17 Mar 2022

Meets Patient’s editorial guidelines

- DownloadDownload

- Share

- Language

- Discussion

- Audio Version

Medical Professionals

Professional Reference articles are designed for health professionals to use. They are written by UK doctors and based on research evidence, UK and European Guidelines. You may find the Drug allergy article more useful, or one of our other health articles.

In this article:

Continue reading below

What is Stevens-Johnson syndrome?1

Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS) is an immune-complex-mediated hypersensitivity disorder. Stevens-Johnson syndrome ranges from mild skin and mucous membrane lesions to a severe, sometimes fatal systemic illness, toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN). Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis are characterised by detachment of the epidermis and mucous membrane. They are mainly, but not always, caused by drugs.

SJS and TEN are considered to be on the same spectrum of diseases with different severities. They are classified by the percentage of skin detachment area. SJS and TEN can also cause complications in the liver, kidneys, and respiratory tract.

Erythema multiforme (EM) was previously considered to be a milder form of SJS without mucosal involvement; however, the clinical classification defined by Bastuji-Garin in 1993 separates EM as a clinically and aetiologically distinct disorder and has now been accepted by consensus.

Classification

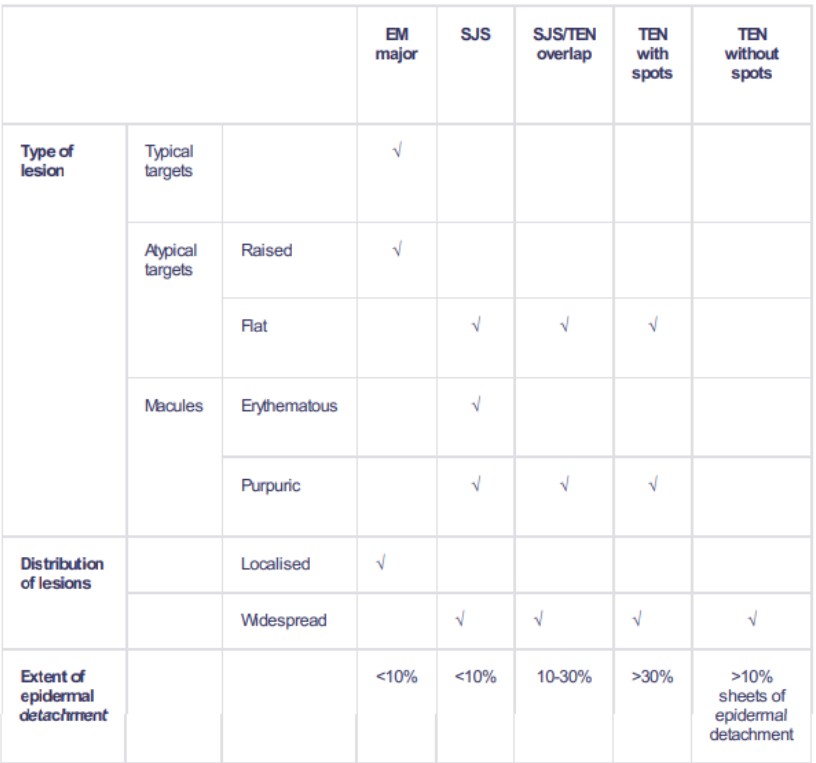

Back to contentsThe classification is based on the percentage of body surface area detached2 3 .

SJS classification

Continue reading below

Epidemiology

Back to contentsStevens-Johnson syndrome incidence is estimated at 1-2 cases/million population/year.2

Stevens-Johnson syndrome is much more common in individuals with HIV. (Estimated 1-2/1,000 in Canada4 .)

Stevens-Johnson syndrome is more common in females than in males.

Most patients are aged 10-30 but cases have been reported in younger children, who have a higher mortality risk5 .

Risk factors6

The rarity of Stevens-Johnson syndrome has made it difficult to clearly ascertain specific risk factors among heterogeneous populations; however, the presence of particular HLA alleles has been found to be associated with SJS/TEN among particular groups - for example:

HLA B1502 and HLA B1508 among the Han Chinese have been found to be associated with SJS/TEN in reaction to carbamazepine and allopurinol respectively.

HLAb 5701 abacavir is associated with SJS/TEN among people living with HIV.

Screening for these genes among specific populations, before commencing medications, may help to avert occurrence of the disease among these groups.

Stevens-Johnson syndrome causes (aetiology)7

Back to contentsApproximately 75% of SJS/TEN are caused by medications and 25% by infections and other causes.

Drugs most commonly associated with SJS and TEN

Allopurinol

Carbamazepine

Sulfonamides:

Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole.

Sulfadiazine.

Sulfasalazine.

Antiviral agents:

Nevirapine.

Abacavir.

Anticonvulsants:

Phenobarbital.

Phenytoin.

Valproic acid.

Lamotrigine.

Others:

Imidazole antifungal agents.

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (oxicam type such as meloxicam).

Salicylates.

Sertraline.

Bupropion (rarely).

Infection

Viral: includes herpes simplex virus, Epstein-Barr virus, enteroviruses, HIV, Coxsackievirus, influenza, hepatitis, mumps, lymphogranuloma venereum, rickettsia and variola.

Bacterial: includes Group A beta-haemolytic streptococcus, diphtheria, brucellosis, mycobacteria, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, tularaemia and typhoid.

Fungal: includes coccidioidomycosis, dermatophytosis and histoplasmosis.

Protozoal: malaria and trichomoniasis.

Immunisation

Associated with immunisation - eg, measles, hepatitis B.

Continue reading below

Stevens-Johnson syndrome presentation8 9 10

Back to contentsSee images available under 'Further reading' section, below.

Stevens-Johnson syndrome symptoms

Stevens-Johnson syndrome symptoms often starts with a nonspecific upper respiratory tract infection, which may be associated with fever, sore throat, chills, headache, arthralgia, vomiting and diarrhoea, and malaise.

Mucocutaneous lesions develop suddenly and clusters of outbreaks last from 2-4 weeks. The lesions are usually not pruritic.

Mouth: severe oromucosal ulceration.

Respiratory involvement may cause a cough productive of a thick purulent sputum.

Patients with genitourinary involvement may complain of dysuria or an inability to pass urine.

Ocular symptoms: painful red eye, purulent conjunctivitis, photophobia, blepharitis.

Signs

General examination: fever, tachycardia, hypotension; altered level of consciousness, seizures, coma.

Skin:

Lesions may occur anywhere, but most commonly affect the palms, soles, dorsum of hands and extensor surfaces. The rash may be confined to any one area of the body, most often the trunk.

The rash can begin as macules that develop into papules, vesicles, bullae, urticarial plaques, or confluent erythema.

The centre of the lesions may be vesicular, purpuric, or necrotic.

The typical lesion has the appearance of a target, which is considered pathognomonic.

Lesions may become bullous and later rupture. The skin becomes susceptible to secondary infection.

Urticarial lesions are usually not pruritic.

Nikolsky sign is positive (mechanical pressure to skin leading to blistering within minutes or hours).

Mucosal involvement: erythema, oedema, sloughing, blistering, ulceration and necrolysis.

Eye: conjunctivitis, corneal ulcerations.

Genital: erosive vulvovaginitis or balanitis.

Stevens-Johnson syndrome differential diagnosis7

Back to contentsAcute generalised exanthematous pustulosis.

Bullous phototoxic reactions.

Chemical or thermal burns.

Maculopapular drug rashes.

Paraneoplastic pemphigus acantholysis.

Investigations

Back to contentsSerum electrolytes, glucose and bicarbonate are essential to assess clinical severity and level of dehydration8 .

Stevens-Johnson syndrome diagnosis is based on clinical classification - as in the table, above - and on histopathology.

Skin biopsy: demonstrates that the bullae are subepidermal. Epidermal cell necrolysis may be seen and perivascular areas are infiltrated with lymphocytes.

Stevens-Johnson syndrome treatment and management3 7 11 12

Back to contentsMultidisciplinary management of eyes, mucous membranes (gynae, mouth, gastrointestinal tract) helps to improve outcomes and reduce adverse sequelae.

Acute phase:

identify and remove causative drug or underlying cause.

Use of the ALDEN (Algorithm for assessment of Drug-induced Epidermal Necrolysis) may be useful10 .

A rapid assessment of prognosis should be made using the SCORTEN (Score for Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis) system. SCORTEN is an illness severity score which has been developed to predict the mortality rate in SJS and TEN. One point is given for each of seven criteria present at the time of admission. The seven criteria are:

Age >40.

Presence of malignancy.

Heart rate >120 beats per minute.

Initial percentage of epidermal detachment >10%.

Serum bicarbonate <20 mmol/L.

Serum urea >10 mmol/L.

Serum glucose >14 mmol/L.

Patients with a SCORTEN score of >3 should be managed in intensive care.

Supportive:

Attention to airway and haemodynamic stability.

Severe fluid loss may require intravenous fluid replacement and electrolyte correction.

Pain control.

Skin lesions are treated in the same way as for burns.

Mouth: mouthwashes; topical anaesthetics are useful in reducing pain and allowing the patient to take in fluids.

Eye care: frequent ophthalmology assessment and frequent eye drops, including antibiotic and steroid when required.

Treat secondary infections.

Immunomodulation:

The use of corticosteroids is controversial due to the need to balance dampening of the aberrant immune response with poor healing and increased risk of infection. Some progress has been made with the use of pulsed systemic corticosteroids.

Some have advocated ciclosporin, cyclophosphamide, anti-TNFalpha monoclonal antibodies, plasmapheresis, haemodialysis and immunoglobulin therapy in the acute phase; however, none is considered to be standard at this time.

Some reports have found early administration of high-dose intravenous immunoglobulin to be associated with increased mortality in SJS and TEN; this is, therefore, no longer recommended.

Stevens-Johnson complications2 10

Back to contentsDehydration and acute malnutrition.

Shock and multiorgan failure.

Thromboembolism and disseminated intravascular coagulation.

Gastrointestinal ulceration, necrolysis, strictures and perforation.

Skin: secondary infection and scarring.

Mucosal pseudomembrane formation may lead to mucosal scarring and loss of function of the involved organ system.

Lung: mucosal shedding in the tracheobronchial tree may lead to respiratory failure.

Eye complications: include corneal ulceration and anterior uveitis. Sight impairment may develop secondary to severe keratitis or panophthalmitis in 3-10% of patients.

Vaginal stenosis and penile scarring have been reported.

Renal complications are uncommon but renal tubular necrolysis and acute kidney injury may occur.

Stevens-Johnson syndrome prognosis and sequelae3 8

Back to contentsMany patients surviving SJS and more that 50% surviving TEN experience long-term sequelae involving the skin, mucous membranes or eyes. These include:

Skin: hyperhidrosis, xeroderma, reversible hair loss, heat and cold sensitivity, scarring and irregular pigmentation.

Nail dystrophy.

Mucous membranes: vaginal, urethral and anal strictures. Persistent mucosal erosions.

Ocular: xerophthalmia, photophobia, symblepharon, synechiae, entropion, meibomian gland dysfunction and sight impairment.

The overall mortality rate is up to 10% for SJS and at least 30% for TEN. However, the mortality rate correlates with the SCORTEN score and is greater than 90% for people with a SCORTEN score of 5 or more2 . The high mortality rate results primarily from the development of complications in the form of systemic infections and multiple organ failure13 .

Stevens-Johnson syndrome prevention

Back to contentsFuture avoidance of any possible or confirmed underlying cause6 .

Screening for particular HLA alleles in particular groups.

Further reading and references

- Stevens Johnson Syndrome/Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis; DermNet NZ

- Stevens-Johnson Syndrome; DermIS (Dermatology Information System)

- Hasegawa A, Abe R; Recent advances in managing and understanding Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis. F1000Res. 2020 Jun 16;9. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.24748.1. eCollection 2020.

- Stevens Johnson Syndrome and Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis; DermNet NZ

- Schneider JA, Cohen PR; Stevens-Johnson Syndrome and Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis: A Concise Review with a Comprehensive Summary of Therapeutic Interventions Emphasizing Supportive Measures. Adv Ther. 2017 Jun;34(6):1235-1244. doi: 10.1007/s12325-017-0530-y. Epub 2017 Apr 24.

- Mittmann N, Knowles SR, Koo M, et al; Incidence of toxic epidermal necrolysis and Stevens-Johnson Syndrome in an HIV cohort: an observational, retrospective case series study. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2012 Feb 1;13(1):49-54. doi: 10.2165/11593240-000000000-00000.

- Liotti L, Caimmi S, Bottau P, et al; Clinical features, outcomes and treatment in children with drug induced Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis. Acta Biomed. 2019 Jan 29;90(3-S):52-60. doi: 10.23750/abm.v90i3-S.8165.

- Phillips EJ, Chung WH, Mockenhaupt M, et al; Drug hypersensitivity: pharmacogenetics and clinical syndromes. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011 Mar;127(3 Suppl):S60-6.

- Frantz R, Huang S, Are A, et al; Stevens-Johnson Syndrome and Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis: A Review of Diagnosis and Management. Medicina (Kaunas). 2021 Aug 28;57(9). pii: medicina57090895. doi: 10.3390/medicina57090895.

- Harr T, French LE; Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis. Chem Immunol Allergy. 2012;97:149-66. Epub 2012 May 3.

- Guerry MJ, Lemyze M; Acute skin failure. BMJ. 2012 Aug 6;345:e5028. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e5028.

- Shanbhag SS, Chodosh J, Fathy C, et al; Multidisciplinary care in Stevens-Johnson syndrome. Ther Adv Chronic Dis. 2020 Apr 28;11:2040622319894469. doi: 10.1177/2040622319894469. eCollection 2020.

- Zimmermann S, Sekula P, Venhoff M, et al; Systemic Immunomodulating Therapies for Stevens-Johnson Syndrome and Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Dermatol. 2017 Jun 1;153(6):514-522. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.5668.

- Charlton OA, Harris V, Phan K, et al; Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis and Steven-Johnson Syndrome: A Comprehensive Review. Adv Wound Care (New Rochelle). 2020 Jul;9(7):426-439. doi: 10.1089/wound.2019.0977. Epub 2020 Jan 9.

- Hinc-Kasprzyk J et al; Toxic epidermal necrolysis. Anaesthesiol Intensive Ther. 2015, 47(3):257-62.

Continue reading below

Article history

The information on this page is written and peer reviewed by qualified clinicians.

Next review due: 16 Mar 2027

17 Mar 2022 | Latest version

Ask, share, connect.

Browse discussions, ask questions, and share experiences across hundreds of health topics.

Feeling unwell?

Assess your symptoms online for free