Lung cancer

Peer reviewed by Dr Hayley Willacy, FRCGP Last updated by Dr Colin Tidy, MRCGPLast updated 21 Sept 2022

Meets Patient’s editorial guidelines

- DownloadDownload

- Share

Lung cancer (cancer of the lung) is common worldwide. Around 4 in 10 cases develop in people over the age of 75 years, usually in smokers. If lung cancer is diagnosed at an early stage, there is a chance of a cure. In general, the more advanced the cancer (the more it has grown and spread), the less chance that treatment will be curative. However, treatment can often slow the progress of the cancer.

In this article:

Continue reading below

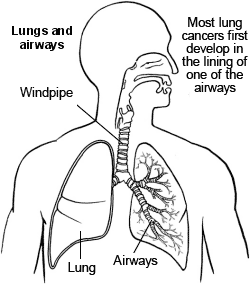

What are the lungs?

Upper and lower respiratory tract detail

There are two lungs, one on either side of the chest. Air goes into the lungs via the windpipe (trachea) which divides into a series of branching airways called bronchi. Air goes from the airways into millions of tiny air sacs (alveoli).

Oxygen from the air is passed into the bloodstream through the thin walls of the alveoli.

Patient picks for Lung cancer

Cancer

Can a new blood test detect lung cancer early?

New research suggests that a ground-breaking blood test could reduce the number of deaths from lung cancer each year.

by Milly Evans

Cancer

Mesothelioma

Mesothelioma is an uncommon type of cancer that occurs in the tissues covering internal organs, particularly your lungs or less commonly your tummy (abdomen). Past exposure to asbestos is the main risk factor for mesothelioma. The first symptoms are variable but can include shortness of breath, chest pain or abdominal swelling. It is not usually possible to cure mesothelioma but there are different treatments to help with symptoms.

by Dr Colin Tidy, MRCGP

What is lung cancer?

Lung cancer is one of the most common cancers in the UK. There are about 38,000 new cases diagnosed each year in the UK.

What is lung cancer?

Primary lung cancers

Primary lung cancers arise from cells in the lung. There are several types of primary lung cancer. The two most common types are called small-cell lung carcinoma (SCLC) and non-small-cell lung carcinoma (NSCLC).

NSCLCs include squamous cell cancers (the most common type of lung cancer), adenocarcinoma and large-cell carcinoma. About 1 in 5 cases of lung cancer are SCLC; the remainder is NSCLC. All these types of lung cancer arise from various cells which line the airways (bronchi). There are some other rarer types of primary lung cancer which arise from other types of cells in the lung.

Each type of lung cancer has different properties. For example, small-cell carcinoma grows and spreads (metastasises) rapidly. By the time small-cell cancer is diagnosed, in most cases it has already spread to other parts of the body. In contrast, a squamous cell carcinoma tends to grow more slowly and may not spread to other parts of the body for some time.

Secondary lung cancers

Secondary lung cancers (or lung metastases) are tumours which have spread to the lung from another cancer somewhere else in the body. The lung is a common site for metastases from other cancers. This is because all blood flows through the lungs and may contain tumour cells from any other part of the body.

Secondary lung cancers are not dealt with further in this leaflet.

Mesothelioma

This is a cancer of a tissue which covers the lungs (the pleura). Strictly speaking, mesothelioma is not a lung cancer. See the separate leaflet called Mesothelioma for more details.

See the separate leaflet called Cancer for more general information about cancer.

Continue reading below

What causes lung cancer?

A cancerous tumour starts from one abnormal cell. It is thought that something damages or alters certain genes in the cell. This makes the cell abnormal and multiply out of control. Certain risk factors increase the chance of certain cancers forming. See the separate leaflet called Causes of Cancer for more details.

Smoking

Smoking is a major risk factor and is the main cause of lung cancer. Chemicals in tobacco smoke are carcinogens. These are substances which can damage cells and cause you to develop lung cancer. About 9 in 10 cases of lung cancer are caused by smoking.

Compared with non-smokers, those who smoke between 1-14 cigarettes a day have eight times the risk of dying from lung cancer. Those who smoke 25 or more cigarettes a day have 25 times the risk. However, the risk of lung cancer depends more on the length of time a person has smoked. So, smoking one pack of cigarettes a day for 40 years is more hazardous than smoking two packs a day for 20 years.

After about fifteen years from stopping smoking, that person's risk of developing lung cancer is similar to that of a non-smoker.

Other factors

Non-smokers have a low risk of developing lung cancer. However, people who are regularly exposed to other people's smoke (passive smokers) have a small increased risk. People who work with certain substances have an increased risk, especially if they also smoke. These substances include radioactive materials, asbestos, nickel and chromium. People who live in areas where there is a high level of background radiation from radon have a small increased risk. Air pollution may be a small risk too.

A family history of lung cancer in a first-degree relative (mother, father, brother, sister) slightly increases the risk of lung cancer. But note: most cases of lung cancer do not run in families.

What are the symptoms of lung cancer?

The symptoms of lung cancer can vary between different people. Many people do not have symptoms in the early stages and lung cancer may be diagnosed when a chest X-ray is performed for a different reason. Initial symptoms of lung cancer may include one or more of the following:

Persistent cough.

Coughing up blood or bloodstained phlegm (sputum).

Chest and/or shoulder pains.

Tiredness and loss of energy.

Weight loss.

Shortness of breath or wheezing - especially if a tumour is growing in a main airway and is partially blocking the airflow.

Hoarse voice.

A change in shape at the end of your fingers (clubbing).

As the cancer grows in the lung, the symptoms may become worse and may include one or more of the following:

The same symptoms as above but more severe.

Lung infection (pneumonia) which may develop in a part of a lung blocked off by a growing tumour. The infection may not improve with antibiotics.

Fluid which may accumulate between the lung and chest wall (pleural effusion). This can cause worsening shortness of breath.

A tumour near to the top of the lung, which can press on nerves going down the arm and cause pain, weakness, and pins and needles in the arm and shoulder.

Swelling of the face (face oedema) which may develop if a tumour presses on a main vein coming towards the heart from the head.

Some small cell tumours can produce large amounts of hormones which can cause symptoms in other parts of your body.

If the cancer spreads to other parts of the body, various other symptoms can develop such as bone pain or swelling of the neck or above the collarbone.

Continue reading below

How is lung cancer diagnosed?

If a doctor suspects that you may have lung cancer, the common initial test is a chest X-ray. This is a simple and quick test and may show changes such as abnormal shadowing. However, a chest X-ray cannot confirm cancer, as there are various other causes of shadowing on a chest X-ray. Other tests are therefore needed.

Editor’s note

Dr Krishna Vakharia, 16th October 2023

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) has recommended that a person should receive a diagnosis or ruling out of cancer within 28 days of being referred urgently by their GP for suspected cancer.

Confirming the diagnosis

You may be offered a computerised tomography (CT) scan and other investigations which will help to confirm the diagnosis of lung cancer. You may need other tests which not only provide more information about the cancer but also help to detect whether it has spread.

Further tests

You may be offered different types of tests depending on the circumstances. If the CT scan shows the cancer is at an early stage and you are fit to be treated, you may be asked to have another type of scan. This is called a positron emission tomography-CT (PET-CT) scan. This shows up areas of active cancer and whether it has spread to the lymph glands in the chest. If the cancer has spread to these glands, you will be offered a biopsy. A small sample will be taken and inspected under a microscope to look for the cancerous cells. The type of cancer can also be determined from the sample. One or more of the following procedures may be done to obtain a sample for testing:

A bronchoscopy is the most common procedure to look into the airways and to obtain a biopsy from a tumour in a main airway. A bronchoscope is a thin, flexible, telescope. It is about as thick as a pencil. The bronchoscope is passed through the nose, down the back of the throat, into the windpipe (trachea) and down into the bronchi. The fibre-optics allow light to shine round bends in the bronchoscope and so the doctor can see clearly inside your airways. A bronchoscope has a side channel down which a thin grabbing instrument can pass. This can be used to take a small biopsy from tissue on the the inside lining of a bronchi.

Instead of taking a biopsy, in some cases it is thought better to perform a bronchial wash. The area of the tumour is flushed with fluid which is then sent off for analysis.

If the CT scan shows that the cancer has spread to the lymph glands in your neck, you may be offered an ultrasound scan with biopsy of the neck glands rather than bronchoscopy.

A fine-needle biopsy is often done where the cancer is at the edge of the lung, where a doctor inserts a thin needle through the chest wall to obtain a small sample of tissue (this is called a trans-thoracic needle biopsy). CT or ultrasound pictures help to guide the doctor to insert the needle into the suspicious area. The skin is numbed with local anaesthetic to make the test as painless as possible.

If you have an accumulation of fluid next to the lung, which may be due to a tumour, some fluid can be drained by a pleural tap with a fine needle (similar to the above). The fluid is examined for cancer cells.

If you are unable to have one of the tests previously described or they have not provided an answer, you may be asked to undergo a small operation to obtain lung tissue for testing.

An endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration (EBUS-TBNA) is a procedure in which a thin bronchoscope is inserted into the lungs. Images of the area between the two lungs (the mediastinum) are obtained using a special ultrasound probe attached to the bronchoscope. A biopsy can be taken at the same time.

Assessing the extent and spread

This assessment is called staging of the cancer. The aim of staging is to find out:

How much the cancer in the lung has grown.

Whether the cancer has spread to local lymph nodes or to other areas of the lungs.

Whether the cancer has spread to other areas of the body (metastasised).

By finding out the stage of the cancer, it helps doctors to advise on the best treatment options. It also gives a reasonable indication of outlook (prognosis).

A magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan is often used to detect the spread of cancer to the brain or bones.

How is lung cancer treated?

Treatment options which may be considered include surgery, and targeted therapies such as chemotherapy and radiotherapy. The treatment advised for each case depends on various factors, such as:

The site of the primary tumour in the lung.

The type of cancer.

The stage of the cancer (how large the cancer is and whether it has spread).

Your general health.

The types of treatment regimes for SCLC and NSCLC can be very different.

You should have a full discussion with a specialist who knows your case. They will be able to give the pros and cons, likely success rate, possible side-effects and details about the possible treatment options for your type of cancer.

You should also discuss with your specialist the aims of treatment. For example:

Treatment may aim to cure the cancer. Some lung cancers can be cured, particularly if they are treated in the early stages of the disease. (Doctors tend to use the word remission rather than the word cured. Remission means there is no evidence of cancer following treatment. If you are in remission, you may be cured. However, in some cases a cancer returns months or years later. This is why doctors are sometimes reluctant to use the word cured.)

Treatment may aim to control the cancer. If a cure is not realistic, with treatment it is often possible to limit the growth or spread of the cancer so that it progresses less rapidly. This may keep you free of symptoms for some time.

Treatment may aim to ease symptoms. Even if a cure is not possible, treatments may be used to reduce the size of a cancer, which may ease symptoms such as pain. If a cancer is advanced, you may require treatments such as nutritional supplements, painkillers, or other techniques to help keep you free of pain or other symptoms.

Surgery

An operation may be an option if the cancer is in an early stage. Surgery usually involves removing part or all of an affected lung. However, in many cases, the cancer has already spread when it is diagnosed and surgery is not usually then an option.

Surgery is not usually performed for people with SCLC. Also, surgery may not be an option if your general health is poor. For example, if you have other lung problems, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), which is also common in smokers.

Radiotherapy

Radiotherapy is a treatment which uses high-energy beams of radiation which are focused on cancerous tissue. This kills cancer cells, or stops cancer cells from multiplying. See the separate leaflet called Radiotherapy for more details.

Radiotherapy may be given to people with SCLC and NSCLC. It is usually offered when the cancer is restricted to the lung or has only spread to nearby lymph glands. It can sometimes result in remission of the cancer if surgery cannot be performed. It may, however, also be used in addition to surgery or chemotherapy.

Radiotherapy is sometimes given to the head (known as prophylactic cranial radiotherapy) to reduce the risk of the cancer spreading to the brain in people with SCLC.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy is a treatment of cancer by using anti-cancer drugs which kill cancer cells, or stop them from multiplying. If you are going to have surgery you will normally be offered this after the operation. See the separate leaflet called Chemotherapy for more details.

Chemotherapy may be given after surgery for NSCLC. This is known as adjuvant chemotherapy. The type of chemotherapy given depends on the type of cancer. Chemotherapy may also be used for some people to treat lung cancer which has spread to other areas of the body.

Other cancer treatments

Radiofrequency ablation is a fairly new technique which involves inserting a small probe into the tumour. A radiofrequency energy is then used to generate heat and kill the surrounding tumour tissue. This is usually done at the same time as having a CT scan which helps to guide the probe. It is most commonly used in people with small early-stage lung cancer for whom surgery is not appropriate.

Photodynamic therapy (PDT) uses low-powered lasers combined with a light-sensitive drug to destroy cancer cells. In the UK it is still only carried out in a few specialist hospitals. PDT is mainly used in clinical trials and is not standard treatment for lung cancer.

Microwave ablation is usually carried out under general anaesthetic. It involves inserting a small probe through the chest wall and delivering high-frequency microwave energy to lung cancer tissue. This heats the tissue, causing cancer cells to die.

The procedure has been found to be safe for most people, but sometimes it can cause serious complications. It is also not clear if it improves quality of life or prolongs survival for people with lung cancer. For these reasons, new guidance from NICE (see Further Reading below) recommends that it is not routinely offered to patients.

What is the outlook (prognosis) for lung cancer?

The outlook is best in those who are diagnosed when the cancer is still small and has not spread. Surgical removal of a tumour in an early stage may then give a good chance of cure. However, most people with lung cancer are diagnosed when the cancer has already spread. In this situation a cure is less likely. However, treatment can often slow down the progression of the cancer.

The treatment of cancer is a developing area of medicine. New treatments continue to be developed and the information on outlook above is very general. The specialist who knows your case can give more accurate information about your particular outlook and how well your type and stage of cancer are likely to respond to treatment.

Further reading and references

- Suspected cancer: recognition and referral; NICE guideline (2015 - last updated April 2025)

- Lung cancer: diagnosis and management; NICE guideline (2019 - updated March 2024)

- ESMO Small-cell lung cancer: Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up; European Society for Medical Oncology (2021)

- Metastatic Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up; European Society for Medical Oncology (2020)

- A list of all publications on lung cancer; National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE).

- Early and locally advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC); ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Annals of Oncology, Volume 28, supplement 4, iv1-iv21, July 2017.

Continue reading below

Article history

The information on this page is written and peer reviewed by qualified clinicians.

Next review due: 20 Sept 2027

21 Sept 2022 | Latest version

Book a free same day online consultation

Get help with common conditions under the NHS Pharmacy First scheme.

Feeling unwell?

Assess your symptoms online for free