Bowel cancer

Colon and rectal

Peer reviewed by Dr Philippa Vincent, MRCGPLast updated by Dr Doug McKechnie, MRCGPLast updated 17 Apr 2023

Meets Patient’s editorial guidelines

- DownloadDownload

- Share

- Language

- Discussion

In this series:Bowel cancer screeningFaecal immunochemical testSigmoidoscopyColonoscopyCT colonographyBowel polyps

Colon cancer and rectal cancer (also called colorectal cancer) are common in the UK. The colon and rectum are parts of your bowel. Most cases occur in people aged over 50. If bowel cancer is diagnosed at an early stage, there is a good chance of a cure.

In general, the more advanced the cancer (the more it has grown and spread), the less chance that treatment will be curative. However, treatment can often slow the progress of the cancer.

In this article:

Video picks for Bowel cancer

What is bowel cancer?

What is bowel cancer?

Bowel cancer is sometimes called colon or rectum cancer, colorectal cancer, or cancer of the large intestine. It is one of the most common cancers in the UK. (In contrast, cancer of the small intestine is rare.)

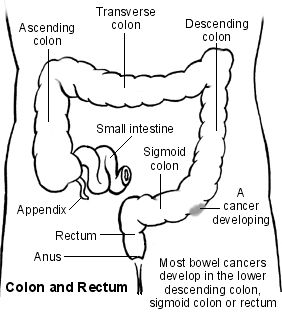

Bowel cancer can affect any part of the colon or rectum. However, it most commonly develops in the lower part of the descending colon, the sigmoid colon, or rectum.

Bowel cancer usually develops from a small fleshy growth (polyp) which has formed on the lining of the colon or rectum (see below). Sometimes bowel cancer begins from a cell within the lining of the colon or rectum which becomes cancerous.

Some rare types of cancer arise from various other cells in the wall of the colon or rectum. For example, carcinoid, lymphoma, and sarcomas. As the cancer cells multiply they form a tumour.

The tumour invades deeper into the wall of the colon or rectum. Some cells may break off into the lymph channels or bloodstream. The cancer may then spread (metastasise) to lymph nodes nearby or to other areas of the body - most commonly, the liver and lungs.

Polyps and bowel cancer

A bowel polyp (adenoma) is a small growth that sometimes forms on the inside lining of the colon or rectum. Most bowel polyps develop in older people. About 1 in 4 people over the age of 50 develop at least one bowel polyp. Polyps are non-cancerous (benign) and usually cause no problems.

However, sometimes a benign polyp can turn cancerous. If one does turn cancerous, the change usually takes place after a number of years. Most bowel cancers develop from a polyp that has been present for 5-15 years.

See the separate leaflet called Cancer for more general information about cancer.

Where are the colon and rectum?

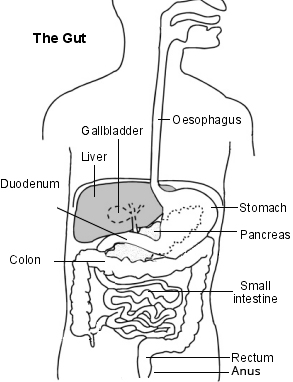

Back to contentsThe colon and rectum are parts of the bowel or gut (gastrointestinal tract). The gut starts at the mouth and ends at the anus. When we eat or drink, the food and liquid travel down the gullet (oesophagus) into the stomach. The stomach churns up the food and then passes it into the small intestine.

Diagram naming the parts of the gut

Large bowel - cancer

The small bowel (small intestine) is several metres long and is where food is digested and absorbed. Undigested food, water and waste products are then passed into the large bowel (large intestine). The main part of the large intestine is called the colon, which is about 150 cm long.

This is split into four sections: the ascending, transverse, descending and sigmoid colon. Some water and salts are absorbed into the body from the colon. The last part of the colon is called the rectum, which is about 15 cm long. The rectum stores stools (faeces) before they are passed out from the anus.

Continue reading below

What causes bowel cancer?

Back to contentsThe exact reason why a cell becomes cancerous is unclear. It is thought that something damages or alters certain genes in the cell. This makes the cell abnormal and multiply out of control.

See the separate leaflet called Causes of Cancer for more details.

Risk factors

Although bowel cancer can develop for no apparent reason, there are certain risk factors which increase the chance that bowel cancer will develop. Risk factors include:

Ageing: bowel cancer is more common in older people. Eight out of ten people who are diagnosed with bowel cancer are older than 60 years.

If a close relative has had bowel cancer (there is some genetic factor).

If you have a genetic condition that causes bowel cancer, such as familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) or hereditary non-polyposis bowel cancer (HNPCC). These account for about 5% of all bowel cancers and are quite rare conditions.

If you have ulcerative colitis or Crohn's disease (conditions of the colon) for more than 8-10 years.

Lifestyle factors: little exercise, drinking a lot of alcohol, smoking, and eating a diet high in red and processed meat.

There is a reduced risk of developing bowel cancer in people who eat a lot of fruit and vegetables.

Bowel cancer symptoms

Back to contentsWhen a bowel cancer first develops and is small it usually causes no symptoms. As it grows, the symptoms and signs of bowel cancer that develop can vary, depending on the site of the tumour.

The most common bowel cancer symptoms to first develop are:

Bleeding from the tumour. You may see blood mixed up with your stools (faeces). Sometimes the blood can make the faeces turn a very dark colour. The bleeding is not usually severe and in many cases it is not noticed, as it is just a small trickle which is mixed with the faeces. However, small amounts of bleeding that occur regularly can lead to anaemia which can make you tired and pale.

Passing mucus with the faeces.

A change from your usual bowel habit. This means you may pass faeces more often or less often than usual, causing bouts of diarrhoea or constipation.

A feeling of not fully emptying the rectum after passing faeces.

Tummy (abdominal) pains.

As the tumour grows in the colon or rectum, symptoms may become worse and can include:

The same symptoms as above, but more severe.

You may feel generally unwell, tired or lose weight.

If the cancer becomes very large, it can cause a blockage (obstruction) of the colon. This causes severe tummy (abdominal) pain and other symptoms such as being sick (vomiting).

Sometimes the cancer makes a hole in the wall of the colon or rectum (perforation). If this occurs, the faeces can leak into the abdomen. This causes severe pain.

If the cancer spreads to other parts of the body, various other symptoms can develop. The symptoms depend on where it has spread to.

All the above symptoms can be due to other conditions, so tests are needed to confirm bowel cancer.

Contact a doctor if you have any of the symptoms mentioned, or if you're worried you might have bowel cancer.

Continue reading below

How is bowel cancer diagnosed?

Back to contentsInitial assessment

If a doctor suspects that you may have bowel cancer, he or she will examine you. The examination will usually include a rectal examination. The doctor inserts a gloved finger through your anus into your rectum to feel if there is a tumour in the lower part of the rectum. However, often the examination is normal, especially if the cancer is in its early stages. Your doctor may also arrange blood tests and a faecal (poo) test called a FIT test.

FIT testing looks for tiny amounts of blood in the poo. It's useful even if you have visible blood in poo (try to take the sample from an area without visible blood). A negative FIT test makes bowel cancer unlikely; a positive FIT test can be caused by many things other than bowel cancer, but usually means that your doctor will refer you to a specialist urgently for further tests.

Editor’s note

Dr Krishna Vakharia, 16th October 2023

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) has recommended that a person should receive a diagnosis or ruling out of cancer within 28 days of being referred urgently by their GP for suspected cancer.

One or more of the following tests may be arranged:

Colonoscopy

A colonoscopy is a test in which a long, thin, flexible telescope (a colonoscope) is passed through your anus into your rectum and colon. This enables the whole of your colon and rectum to be looked at in detail.

Flexible sigmoidoscopy

This is similar to colonoscopy. The difference is that a shorter telescope is used which is inserted only into the rectum and sigmoid colon.

CT colonography

This test uses X-rays to build up a series of images of your colon and rectum. A computer then organises these to create a detailed picture that may show polyps or anything else unusual on the surface of your colon or rectum. This is good for people who are unable to have a colonoscopy, or don't want to have one. However, if anything is seen on the CT scan, it's likely that a colonoscopy will be offered as the next step anyway.

See the separate leaflets called Colonoscopy, Sigmoidoscopy, and CT Colonography.

Biopsy - to confirm the diagnosis

A biopsy entails a small sample of tissue being removed from a part of the body. The sample is then examined under the microscope to look for abnormal cells. If you have a colonoscopy or sigmoidoscopy, the doctor or nurse can take a biopsy of any abnormal tissue. This is done by passing a thin grabbing instrument down a side channel of the colonoscope or sigmoidoscope. It can take up to two weeks for the result of a biopsy.

Assessing the extent and spread of bowel cancer

Back to contentsIf you are confirmed to have bowel cancer, further tests may be done to assess if it has spread. For example, a computerised tomography (CT) scan, a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan, or an ultrasound scan. This assessment is called staging of the cancer. The aim of staging is to find out:

How much the tumour in the colon or rectum has grown, and whether it has grown partially or fully through the wall of the colon or rectum.

Whether the cancer has spread to local lymph nodes.

Whether the cancer has spread to other areas of the body (metastasised).

By finding out the stage of the cancer, it helps doctors to advise on the best treatment options. It also gives a reasonable indication of outlook (prognosis). For bowel cancer, it may not be possible to give an accurate staging until after an operation to remove the tumour. The tumour, node, metastasis (TNM) classification system is being increasingly used to stage bowel cancer. See the separate leaflet called Stages of Cancer for details.

Bowel cancer treatment

Back to contentsTreatment options that may be considered include:

Surgery.

Chemotherapy.

Radiotherapy.

The treatment advised for each case depends on various factors such as the stage of the cancer (how large the cancer is and whether it has spread), and your general health.

You should have a full discussion with a specialist who knows your case. They will be able to give the pros and cons, likely success rate, possible side-effects and other details about the various possible treatment options for your type of cancer.

You should also discuss with your specialist the aims of treatment. For example:

Curing the cancer

Some bowel cancers can be cured, particularly if they are treated in the early stages of the disease. (Doctors tend to use the word remission rather than the word cured. Remission means there is no evidence of cancer following treatment. If you are in remission, you may be cured. However, in some cases a cancer returns months or years later. This is why some doctors are reluctant to use the word cured.)

Controlling the cancer

If a cure is not realistic, with treatment it is often possible to limit the growth or spread of the cancer so that it progresses less rapidly. This may keep you free of symptoms for some time.

Easing symptoms

If a cure is not possible, treatments may be used to reduce the size of a cancer, which may ease symptoms such as pain. If a cancer is advanced then you may require treatments such as nutritional supplements, painkillers or other techniques to help keep you free of pain and any other symptoms.

Surgery

It is often possible to remove the primary tumour surgically. Removing the tumour may be curative if the cancer is in an early stage. The common operation is to cut through the colon or rectum above and below the tumour. The affected section is then removed and, if possible, the two cut ends are sewn together.

Sometimes a temporary colostomy is done to allow the joined ends to heal without stools (faeces) passing through. The colostomy is often reversed in a second operation a few months later when the joined ends of the colon or rectum are well healed.

If the tumour is low down in the rectum, then the rectum and anus need to be removed. You would then need a permanent colostomy.

A colostomy procedure entails an opening (hole) being made through the wall of the tummy (abdomen). A section of colon is then cut and the edges are attached to the opening in the abdominal wall. This is called a stoma and it allows faeces to pass out from the colon into a disposable bag which is stuck over the stoma.

Even if the cancer is advanced and a cure is not possible, surgery may still have a place to ease symptoms. For example, a stent can be inserted to ease a blocked colon.

A stent is a thin metal tube which is placed through a narrowed or blocked section of colon. It can then be opened wide and remains in the colon to prevent a further blockage.

Chemotherapy

One or other of these treatments may be advised depending on the site and stage of the cancer. Chemotherapy is a treatment of cancer by using anti-cancer medicines which kill cancer cells or stop them from multiplying.

Chemotherapy is increasingly being used for people with bowel cancer. Chemotherapy is used:

Sometimes, before surgery, to shrink the tumour and reduce the chances of the cancer coming back (neoadjuvant chemotherapy).

Sometimes, after surgery, to kill any tiny areas of cancer cells left behind and reduce the chances of the cancer coming back (adjuvant chemotherapy).

To treat advanced (metastatic) bowel cancer.

Targeted treatment and immunotherapy

Targeted treatments and immunotherapy are newer medications. Targeted treatments are designed to affect cancer cells selectively. Immunotherapy uses your immune system to kill cancer cells.

Targeted treatments and immunotherapy are used to treat advanced (metastatic) bowel cancer.

Many of the targeted treatments and immunotherapies are only suitable if the cancer has certain genetic changes. These are tested for in the original biopsy sample of the cancer.

Radiotherapy

This is a treatment which uses high-energy beams of radiation which are focused on cancerous tissue. This kills cancer cells, or stops cancer cells from multiplying. It is most commonly used for bowel cancer when the tumour is in the rectum. See the separate leaflet called Radiotherapy for details.

Radiotherapy can be used:

To shrink a tumour before surgery (neoadjuvant radiotherapy).

To kill any tiny deposits of cancer cells left behind after surgery, and reduce the chances of the cancer coming back (adjuvant radiotherapy).

To treat symptoms from metastatic bowel cancer in other organs (palliative radiotherapy).

What is the outlook?

Back to contentsThere has been a substantial improvement in bowel cancer outlook (prognosis) over the past decade. Without bowel cancer treatment, a cancerous tumour in the bowel is likely to become larger and spread to other parts of the body.

However, in many cases it grows slowly and may remain confined to the lining of the colon or rectum for some months before growing through the wall of the colon or rectum, or spreading. You have a good chance of a cure if you are diagnosed and treated when the cancer is in this early stage.

Doctors and researchers often use a statistic called '5-year survival' to estimate prognosis in cancer. This looks at large groups of people and describes how many of them will still be alive at five years after diagnosis. This gives an idea of the prognosis for a group of people, but can't tell exactly what will happen to an individual.

In England and Wales, between 2013 and 2017, the 5-year survival rates for bowel cancer, according to Cancer Research UK, were:

For stage 1 bowel cancer (cancer that has only grown into the inner part of the bowel wall), about 90 out of every 100 people are alive five years after diagnosis.

For stage 2 bowel cancer (cancer that has grown into the inner and outer part of the bowel wall), over 80 out of every 100 people are alive five years after diagnosis.

For stage 3 bowel cancer (cancer that has spread to the lymph nodes), about 70 out of every 100 people are alive five years after diagnosis.

For stage 4 bowel cancer (cancer that has spread to other organs), about 10 out of every 100 people are alive five years after diagnosis.

The treatment of cancer is a developing area of medicine. New treatments continue to be developed and the information on outlook above is very general. Your specialist can give more accurate information about your particular outlook, and how well your type of cancer and stage of cancer are likely to respond to treatment.

Screening for bowel cancer

Back to contentsA screening test aims to detect a disease before it has caused symptoms and when treatment is likely to be curative.

A simple screening test for bowel cancer, which tests for traces of blood in the stools (faeces), has been introduced in the UK. This bowel cancer screening test is offered to all people of certain older ages. In addition, some younger people may be offered screening if they have a higher-than-average risk of developing bowel cancer. There is a separate leaflet called Bowel Cancer Screening that gives details of the screening programme.

Patient picks for Bowel cancer

Tests and investigations

Bowel cancer screening

Bowel (colorectal) cancer is common. The outlook (prognosis) and chance of cure are much better if this cancer is detected at an early stage rather than at a later stage. A screening programme operates in the UK for certain age groups. The aim is to offer an easy screening test to detect bowel cancer when it is at an early stage and before symptoms start. Some people outside the normal screening age who have a high risk of developing bowel cancer are offered extra screening tests.

by Dr Hayley Willacy, FRCGP

Tests and investigations

Faecal immunochemical test

The faecal immunochemical test helps to diagnose bleeding disorders of the gut (intestine).

by Dr Colin Tidy, MRCGP

Further reading and references

- Diagnosis and management of colorectal cancer; Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network - SIGN (December 2011, revised August 2016)

- Bowel cancer statistics; Cancer Research UK

- Suspected cancer: recognition and referral; NICE guideline (2015 - last updated May 2025)

- Colorectal cancer (management in people aged 18 and over); NICE Guidance (2020, last updated December 2021)

- Colorectal cancer; NICE Quality Standard, 2012 - last updated February 2022

- Cervantes A, Adam R, Rosello S, et al; Metastatic colorectal cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guideline for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2023 Jan;34(1):10-32. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2022.10.003. Epub 2022 Oct 25.

Continue reading below

Article history

The information on this page is written and peer reviewed by qualified clinicians.

Next review due: 15 Apr 2028

17 Apr 2023 | Latest version

Ask, share, connect.

Browse discussions, ask questions, and share experiences across hundreds of health topics.

Feeling unwell?

Assess your symptoms online for free

Sign up to the Patient newsletter

Your weekly dose of clear, trustworthy health advice - written to help you feel informed, confident and in control.

By subscribing you accept our Privacy Policy. You can unsubscribe at any time. We never sell your data.