Wilson's disease

Peer reviewed by Dr Doug McKechnie, MRCGPLast updated by Dr Philippa Vincent, MRCGPLast updated 20 Jan 2025

Meets Patient’s editorial guidelines

- DownloadDownload

- Share

- Language

- Discussion

- Audio Version

In this series:Liver function testsGilbert's syndromeJaundiceCirrhosisLiver failurePrimary biliary cholangitis

Wilson's disease is a genetic disorder in which copper builds up in the body, mainly in the liver and brain. Without any treatment, the build-up of copper can cause serious symptoms. Treatment is with medication to remove the excess copper and/or to prevent a further build-up of copper.

In this article:

Video picks for Genetic conditions

Continue reading below

What is Wilson's disease?

Wilson's disease is a condition where too much copper builds up in the body. It is a rare inherited disorder that affects about 1 in 30,000 people. It is named after Dr Samuel Wilson who first described the disorder in 1912.

People who inherit the genetic fault in Wilson's disease are not able to get rid of copper from their body. Copper is a trace metal which is in many foods. Tiny amounts of copper are needed to remain healthy. Normally, the body gets rid of any excess copper. People with Wilson's disease cannot get rid of this excess copper and so it builds up in the body, mainly in the liver, the brain, the layer at the front of the eye (called the cornea) and the kidneys.

Too much copper in the liver cells (the hepatocytes) is harmful and leads to liver damage. Damage to brain tissue mainly occurs in an area called the lenticular nucleus. Hence, Wilson's disease is sometimes also called hepatolenticular degeneration.

What causes Wilson's disease?

Back to contentsIn Wilson's disease, a particular gene on chromosome 13 does not work. The gene is called ATP7B. This gene normally controls the way the liver cells get rid of excess copper. Normally, the liver cells pass out excess copper into the bile. If this process does not work then the copper builds up in liver cells. When the copper storage capacity of the liver cells is exhausted, the copper spills into the bloodstream and deposits copper in other parts of the body, mainly the brain.

Continue reading below

How is Wilson's disease inherited?

Back to contentsWilson's disease is an autosomal recessive disorder. This means that, in order to develop Wilson's disease, two abnormal ATP7B genes must be inherited - one from each parent.

Wilson's inheritance

People who inherit only one copy of the abnormal gene are called carriers. Carriers do not have the disorder, as they have one normal gene which is enough to control the function of copper in the body. However, carriers can pass the abnormal gene on to their children.

How common is Wilson's disease?

About 1 in 100 people are carriers of the ATP7B gene. When two people who carry the abnormal gene have a child, there is a:

1 in 4 chance that the child will have Wilson's disease (by inheriting the abnormal ATP7B gene from both parents).

2 in 4 chance that the child will not have Wilson's disease, but will be a carrier (by inheriting the abnormal ATP7B gene from one parent but the normal gene form the other parent).

1 in 4 chance that the child will not have Wilson's disease, and will not be a carrier (by inheriting the normal gene from both parents).

Wilson's disease symptoms

Back to contentsAlthough the genetic defect is present at birth, it takes several years for copper to build up to a level where it starts to cause damage. Symptoms typically start to develop between the ages of 6 and 20, most commonly in the teenage years, but some people don't start to develop symptoms until middle age.

Liver problems

Symptoms of liver problems often develop first. The toxic effect on the liver cells can cause inflammation of the liver (hepatitis) which may cause:

Yellowing of the skin or the whites of the eyes (jaundice).

Tummy (abdominal) pain.

Episodes of being sick (vomiting).

If left untreated, damage to liver cells causes scarring of the liver (cirrhosis). Eventually, severe cirrhosis and liver failure develop in untreated cases, causing severe problems.

(Note: there are various causes of cirrhosis. Wilson's disease is a very rare cause of cirrhosis.)

Brain problems

As copper deposits in the brain it can cause various symptoms.

Physical symptoms, including:

Tremor in the arms.

Slowness of movement.

Difficulty with speech.

Writing problems.

Difficulty swallowing.

An unsteady walk.

Headaches.

Fits (seizures).

Psychological symptoms, including:

Depression.

Mood swings

Inability to concentrate.

A personality change leading to argumentative and emotional behaviour.

Severe problems. If left untreated, the accumulation of copper in the brain can lead to:

Severe muscular weakness.

Severe rigidity.

Dementia.

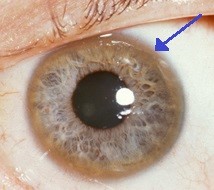

Wilson's disease eyes

Copper may build up in the layer at the front of the eye (called the cornea). This causes a characteristic feature called Kayser-Fleischer rings - a brownish pigmentation of the cornea.

Kayser-Fleischer ring

© Herbert L et al, CC BT 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

By Herbert L et al, CC BT 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Other Wilson's disease features

Other features that may develop include:

Anaemia.

Kidney damage.

Heart problems.

Inflammation of the pancreas (pancreatitis).

Menstrual problems.

Repeated miscarriage in women.

Premature 'thinning' of the bones (osteoporosis).

Continue reading below

How is Wilson's disease diagnosed?

Back to contentsIf Wilson's disease is suspected, it can be diagnosed by various tests:

A blood test to measure caeruloplasmin. This is a protein that binds copper in the bloodstream. The level is low in nearly all people with Wilson's disease.

Other blood tests may also be performed. These may be done to measure the copper levels and to test kidney and liver function.

A specialist may arrange a urine test to measure the amount of copper in the urine over a 24-hour period. The amount is typically higher than normal.

An examination of the layer at the front of the eye (called the cornea) by an optician (optometrist) or an eye specialist may show the Kayser-Fleischer rings if they have developed. (They are not present in all cases.)

A small sample (biopsy) of the liver may be taken to look at under the microscope. This can show the excess copper in the liver and the extent of any scarring of the liver (cirrhosis). See the separate leaflet called Liver biopsy for more details.

Other tests may also be advised - for example, a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan.

If Wilson's disease is confirmed then siblings should be checked to see if they have the condition. Brothers and sisters of a person with Wilson's disease have a 1 in 4 chance of also having the condition.

Wilson's disease treatment

Back to contentsIt is essential to treat Wilson's disease as, without treatment, it can be fatal. The earlier treatment is started, the better the chance of preventing long-term permanent damage to the liver or brain. There is no cure for Wilson's disease but treatment reduces the risks of complications.

Penicillamine is a medicine called a chelating agent and is used to remove copper from the body. The penicillamine causes the excess copper from the body to be passed out in the urine. The dose may be reduced to a maintenance dose after about a year when the initial build-up of copper has been cleared. Unfortunately, the symptoms of Wilson's disease can deteriorate as a side effect of the medication.

Trientine is an alternative to penicillamine. It too is a chelating agent and removes copper from the body. It has slightly fewer side effects.

Zinc is an option in certain circumstances. Zinc works by blocking the gut from absorbing copper from food. Therefore, it does not clear excess copper from the body, but prevents any further build-up of copper. Zinc is much less likely than penicillamine or trientine to cause side-effects. It may be an option for people who are diagnosed at the very early stages of the disease and have no symptoms. Also, a switch to zinc may be an option for people who have been initially treated with penicillamine or trientine once the initial build-up of copper has been cleared from the body. Zinc may also be taken by pregnant women.

Note: treatment is needed for life. First, it is used to clear the excess copper and then to prevent future accumulation of copper. Failure to take medication can lead to a return to a build-up of copper, which can be serious - even fatal.

For the few people who do not respond to treatment with medication, or are diagnosed in the late stage of the disease with severe scarring of the liver (cirrhosis) or liver failure, a liver transplant may be an option. This can be life-saving. The long-term outlook after a liver transplant is usually very good.

Diet

Foods with a high concentration of copper generally should be avoided, at least in the first year of treatment when the excess copper is being cleared from the body. These include liver, chocolate, nuts, mushrooms and shellfish, especially lobster.

Complications of Wilson's disease

Back to contentsIf treatment is begun in the early stages of the disease, it usually works very well. A normal length and quality of life can be expected.

However, without any treatment, Wilson's disease is usually fatal - typically before the age of 40.

If symptoms have developed before treatment has started, some of the symptoms improve with treatment but some may remain permanently. For example, some of the brain symptoms are permanent once they develop. A specialist will be able advise about which symptoms may go and which may be permanent, once treatment begins.

Patient picks for Genetic conditions

Children's health

Ehlers-Danlos syndrome

The Ehlers-Danlos syndromes (EDS) are a group of conditions that affect the stretchiness and strength of supporting tissues in the body, including skin, joints, blood vessels and internal organs. They vary in their impact from very mild through to very severe.

by Dr Rachel Hudson, MRCGP

Children's health

Congenital heart disease

Congenital heart disease is a condition where an abnormality (defect) develops in the heart before birth. There are a number of types of congenital heart defect. Some are mild and cause few problems; others are life-threatening for the baby.

by Dr Mary Harding, MRCGP

Further reading and references

- British Liver Trust

- Wilson Disease; Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM)

- EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: Wilson's disease. J Hepatol. 2012 Mar;56(3):671-85. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.11.007.

- Children's Liver Disease Foundation

- Wilson's Disease Support Group UK

- Purchase R; The treatment of Wilson's disease, a rare genetic disorder of copper metabolism. Sci Prog. 2013;96(Pt 1):19-32.

- Aggarwal A, Bhatt M; Update on Wilson disease. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2013;110:313-48. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-410502-7.00014-4.

- Bandmann O, Weiss KH, Kaler SG; Wilson's disease and other neurological copper disorders. Lancet Neurol. 2015 Jan;14(1):103-13. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(14)70190-5.

Continue reading below

Article history

The information on this page is written and peer reviewed by qualified clinicians.

Next review due: 19 Jan 2028

20 Jan 2025 | Latest version

Ask, share, connect.

Browse discussions, ask questions, and share experiences across hundreds of health topics.

Feeling unwell?

Assess your symptoms online for free

Sign up to the Patient newsletter

Your weekly dose of clear, trustworthy health advice - written to help you feel informed, confident and in control.

By subscribing you accept our Privacy Policy. You can unsubscribe at any time. We never sell your data.