Primary biliary cholangitis

PBC

Peer reviewed by Dr Toni Hazell, MRCGPLast updated by Dr Hayley Willacy, FRCGP Last updated 31 Oct 2022

Meets Patient’s editorial guidelines

- DownloadDownload

- Share

- Language

- Discussion

- Audio Version

Primary biliary cholangitis (PBC) is a condition that slowly damages the bile ducts in your liver, leading to liver damage and, sometimes, liver scarring (cirrhosis).

In this article:

Video picks for Liver and gallbladder

Continue reading below

What is primary biliary cholangitis?

Primary biliary cholangitis (PBC) is an auto-immune condition in which your immune system gradually destroys the tiny tubes (bile ducts) which take bile from the liver to the gut (intestine). The trapped bile then builds up in your liver, where it causes inflammation and damage to liver cells. This can eventually (usually after many years) lead to scarring of the liver (cirrhosis).

Primary biliary cholangitis is called:

Primary - because it is not secondary to any known cause such as alcohol.

Biliary - because it affects the bile ducts.

Cholangitis - because there is inflammation of the bile ducts.

Primary biliary cholangitis symptoms

Back to contentsAs many as half of people with PBC have no symptoms when they are diagnosed: PBC is sometimes diagnosed by chance when blood tests that have been done for other reasons show abnormalities which are due to PBC. Some of these people never develop symptoms. However, many will develop symptoms at some point as the disease progresses. Some patients are diagnosed when their doctor examines them and notices that the liver is a little enlarged, then arranges blood tests to look for the reason why.

When symptoms of PBC do occur they tend to come on gradually, and initially they are vague and may not be noticed. They usually include the following:

Tiredness (fatigue) occurs in about 8 out of every 10 patients. Often the earliest symptom, this can become quite a disabling tiredness and is mainly a daytime sleepiness. The reason PBC causes such severe tiredness is not clear. However, tiredness is a common condition with many possible causes (and most tiredness will not be caused by PBC).

Itch (pruritus). This is a common symptom, seen in up to 7 out of 10 patients. It is sometimes severe and distressing, with the whole skin feeling itchy. It is usually worse at night when lying in bed. The cause of the itch is not always clear. It is most likely to be due to chemicals from the bile, which build up in the bloodstream. It can be difficult to treat adequately but often eases over time.

Discomfort over the liver - upper right of the tummy (abdomen). This occurs in about 1 in 5 cases, probably as the liver becomes inflamed.

Red or pink blotchiness of the hands is fairly common.

Some people develop a feeling of sickness (nausea), bloating or diarrhoea. Stools (faeces) may be pale, bulky and difficult to flush away (this is called steatorrhoea). This is because your body's difficulty with digesting fat when you have PBC means that fat is not well absorbed and is present in the stools.

Going off alcohol and (for smokers) cigarettes is common.

An underactive thyroid gland (hypothyroidism) is present in about 2 out of every 10 people diagnosed with PBC. It is important to treat this, as it will otherwise make tiredness worse.

Sjögren's syndrome (dry eyes and dry mouth) is commonly associated with PBC.

When a doctor examines you, he or she may be able to feel that your liver is enlarged.

Early in the condition there may be few or no specific signs for the doctor to find.

As the disease progresses, yellowing of the skin and the whites of the eyes (jaundice) develops. This is due to a build-up of a chemical in bile (bilirubin) in the bloodstream.

Continue reading below

***Primary biliary cholangitis complications***

Back to contentsThe main complication of PBC is severe liver disease, which has many possible symptoms and complications. The complications of severe liver disease include:

Weight loss and nutritional deficiency.

Poor healing.

Greatly reduced immunity and susceptibility to infections.

Easy bruising and bleeding.

Bleeding into the bowel and stomach may occur.

Stomach ulcers are more common.

There may be swelling of the stomach (ascites) due to fluid leak from the liver.

Varicose veins may appear on stomach and legs.

Severe liver failure causes confusion and drowsiness.

Further, secondary problems develop as a consequence of liver disease, including 'thinning' of the bones (osteoporosis), hyperlipidaemia and nutritional deficiencies.

The risk of developing osteoporosis is increased in women with PBC. See the separate leaflet called Osteoporosis for more details.

Problems with the kidneys and pancreas can occur secondarily to problems with the liver.

Liver cancer is a very uncommon complication of PBC.

***Primary biliary cholangitis diagnosis***

Back to contentsBlood tests

If PBC is suspected from your symptoms, a blood test will usually confirm the diagnosis. Most people with PBC have:

A high level of certain liver chemicals (enzymes) in the bloodstream. See the separate leaflet called Liver function tests for more details.

An antibody called antimitochondrial antibody. This antibody is thought to have something to do with causing the disease, as it attacks a part of the internal working apparatus of cells called the mitochondria. It is present in about 19 out of 20 patients with PBC.

Other unusual antibodies are often found.

Many people with early PBC also have a raised cholesterol level. However, this is usually mainly the good cholesterol which is called high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol. This means that despite having higher cholesterol, there is no increased risk of heart disease. See the separate leaflet called High Cholesterol for more information.

Many people with PBC have an underactive thyroid gland (hypothyroidism).

Ultrasound scan

Your doctor may arrange for you to have an ultrasound scan of your liver. Gel is applied to the skin of your tummy (abdomen). The ultrasound probe is moved across your skin (similar to the scan that women have during pregnancy). This allows the doctor to look at your bile ducts for signs of scarring and blockage. The doctor can also check for any other possible causes of your symptoms.

Liver biopsy

A liver biopsy involves taking a small sample of tissue from a part of the liver. This involves a local anaesthetic and the passage of a hollow needle between two lower ribs on the right-hand side. This enables a tiny piece of liver tissue to be taken. The sample is then examined under the microscope to look for abnormal cells.

If PBC is present then typical changes are seen under the microscope. The biopsy can also give an indication of how severe the condition is. For example, whether liver scarring (cirrhosis) has developed, and if so, how badly. See the separate leaflet called Liver Biopsy for more details.

MRI scan

A magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan and other further specialised testing may be done if your doctors want to rule out other conditions which can be similar to PBC, particularly a condition called primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) which is more common in young men and which has a similar name and behaviour but a different cause.

Continue reading below

Primary biliary cholangitis treatment

Back to contentsIf you are diagnosed with PBC you will be under the care of a consultant specialising in liver disorders, and will probably also have access to a specialist nurse for day-to-day advice. There is no specific curative treatment for PBC. The treatments you are offered will depend on your symptoms, on the stage that your disease has reached and on how rapidly things are changing.

Treatment focuses on:

Treatments to reduce symptoms.

Treatments to slow the course of the disease.

Replacement of the liver.

What are the treatment options to stop the itching?

Itch (pruritus) can be a distressing symptom and can be difficult to treat.

The most commonly used medicine for itch caused by liver disease is colestyramine (trade name Questran®). Colestyramine works by binding to bile in the gut to stop it from making its way back to the liver. When bile gets into the gut, it travels down to the large intestine. Here, some of it is taken (absorbed) back into the bloodstream and returns to the liver to be reused. As colestyramine binds to bile in the large intestine, it stops this reabsorption and so more bile than usual is passed out with the stools (faeces). This helps to reduce the build-up of bile in the liver and bloodstream, which often eases itch. There may be a delay of 1-4 days after starting treatment before itch improves. Other bile-binding medicines are sometimes used.

Other medicines sometimes used to ease itch if colestyramine is not helpful include antihistamines and an antibiotic called rifampicin. Ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) - see below - may also relieve itch.

Plasmapheresis, which is like a plasma exchange, has been used in some cases of persistent, severe itch. It may need to be repeated but seems to be effective.

Dry skin can make itch worse, so using liberal amounts of moisturiser is useful if you have dry skin. It can help to keep the moisturiser cool.

Crotamiton is an anti-itch medication which is sometimes added to moisturiser to help relieve itch. Moisturising creams containing menthol may also be helpful as they give a cooling feeling to the skin.

Keeping cool will also tend to reduce itch, compared to being warm. Cool showers or cold flannels may be helpful.

Scratching will generally make it worse, as scratching heats the skin and brings itch-generating substances to the surface. If scratching is irresistible it may help to rub the itchy area with an ice cube, which both satisfies the need to rub it and cools it down at the same time.

Naloxone (more commonly known as a treatment for opiate overdose) can be helpful.

The antidepressant sertraline can be helpful both for itch and for low mood associated with tiredness.

What are the treatment options for the tiredness?

No medicines seem clearly to ease tiredness (fatigue) which is often a main symptom. A medicine called modafinil (usually used in narcolepsy) is sometimes helpful.

Tiredness is a depressing feeling, particularly when it is unrelenting. If you are affected then finding ways to distract from the physical tiredness, such as by watching films or listening to music, may be helpful. Antidepressants may be helpful, particularly sertraline which can also help with itch.

What treatment slows the progression of the disease?

There is no medicine that stops or reverses the disease. However, some medicines may slow down the progression of the disease in some people:

Ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) is the most common medicine used, with the aim of slowing the progression of the disease. It works by changing the 'makeup' of bile in the liver. This may reduce the harmful effect of bile on the liver cells. UDCA it does not work in everyone. It seems to work best in the early stages of PBC, when it appears to slow disease progression, and may prolong the time for which patients with PBC feel well. It seems to be less effective in the later stages of PBC (in people who have developed scarring of the liver (cirrhosis)). It may help to ease itch and jaundice, as it reduces the levels of some of the increased liver by products in the blood.

Immunosuppressive medicines are sometimes used, including penicillamine, azathioprine, methotrexate, ciclosporin and steroids. These work by suppressing the immune system. These medicines are sometimes used alongside UDCA, particularly in those patients who don't respond well to it. They also all have a risk of causing significant side-effects, and need to be carefully monitored.

A new group of medicines called biologics looks promising as treatment for autoimmune diseases like PBC. Research continues in this area.

Obeticholic acid (Ocaliva) and bezafibrate are new additional treatments for PBC. They work best in combination with UDCA. They have not yet been proved to slow disease progression, although they work to lower the levels of one of the liver enzymes which indicates bile duct blockage.

What about the diseases associated with primary biliary cholangitis?

Various other autoimmune diseases are more common in people with PBC. You may need treatment for these too.

'Thinning' of the bones (osteoporosis) is more common in women with PBC. The prevention and treatment of osteoporosis are the same as for any other woman. They are discussed in the separate leaflet called Osteoporosis.

What is the treatment for cirrhosis and liver failure?

A liver transplant is an option if the liver becomes badly damaged due to cirrhosis. This is a major operation and is not to be undertaken lightly. However, it can be a life-saving measure and the results are often very good, with around 9 out of every 10 patients recovering extremely well.

Some people with severe itch which has not responded to any other treatment have a liver transplant even if their liver is not too badly damaged. This is because severe itch is an extremely distressing symptom which can severely reduce their quality of life.

Sometimes, PBC can come back and affect the transplanted liver. However, this does not necessarily happen and, if it does, can take up to 15 years before it returns. It is not usually severe, so that another liver transplant does not generally become necessary.

See the separate leaflet called Cirrhosis for more details about cirrhosis.

What happens in primary biliary cholangitis?

In PBC, inflammation develops around the small bile ducts within the liver, which gradually become blocked due to this inflammation. This process gets worse very slowly, and the number of damaged and blocked bile ducts gradually increases.

As bile cannot flow down bile ducts, it builds up in the liver cells which eventually become inflamed and then damaged by the accumulation of bile. The substances in bile may also spill over into the bloodstream, causing itching and yellowing of the whites of your eyes and your skin (jaundice).

In the early stages of the disease, the main problems caused by PBC are due to the build-up of substances in the liver and bloodstream which would normally be drained into the first part of the gut (small intestine), known as the duodenum, as part of bile.

As damage to the liver cells gets worse, scarring (cirrhosis) may begin in the liver. The scarred liver cannot function properly and over time liver failure may develop. Cirrhosis occurs only in the later stages of the disease. The rate of decline from early stages of the disease to the later, more serious, stages of the disease can vary from person to person.

Not all people with PBC develop cirrhosis. If cirrhosis does occur, it typically develops several years after the disease first begins.

Is primary biliary cholangitis the same as primary sclerosing cholangitis?

Primary biliary cholangitis (PBC) is not to be confused with primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC). Both conditions cause problems with the bile ducts but PSC mainly affects men and affects a younger age group than PBC. This leaflet is about primary biliary cholangitis.

For information on PSC, see the separate leaflet called Primary sclerosing cholangitis.

What are bile and bile ducts?

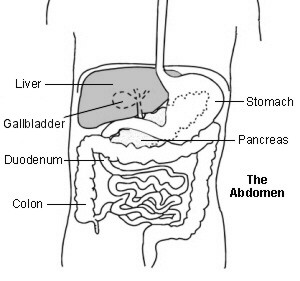

Upper abdomen showing bile ducts

Bile is a yellow-green liquid that contains various chemicals and bile salts. Bile helps you to digest food, particularly fatty foods. It also helps the body to absorb certain vitamins (A, D, E and K) from the food that you eat.

Bile is made by liver cells. Liver cells pass out bile into a network of tubes called bile ducts. These join together to form the larger common bile duct. Bile is constantly formed and drips down the tiny bile ducts, into the common bile duct. It is then stored in the gallbladder, which squeezes it out into the duodenum when you eat food containing fats.

The gallbladder is a pouch off the common bile duct; it lies under the bottom, front edge of the liver. It is a reservoir that stores bile but it also concentrates it. The gallbladder squeezes (contracts) when we eat, as the bile is needed to aid digestion. This empties the stored bile back into the common bile duct and out into the duodenum.

What does the liver do?

Liver function

The liver is in the upper right part of the tummy (abdomen). Its functions include:

Storing glycogen (fuel for the body) which is a starch made from sugars. It acts as 'quick access' energy for the body. When required, glycogen can be quickly broken down into glucose which is released into the bloodstream.

Helping to process fats and proteins from digested food.

Making proteins that are essential for blood to clot (clotting factors).

Processing many medicines which you may take.

Helping to remove or process alcohol, poisons and toxins from the body.

Making bile which passes from the liver to the gut and helps to digest fats.

How does primary biliary cholangitis happen?

The immune system normally defends us by attacking bacteria, viruses, and other germs with antibodies, white blood cells, and other defence mechanisms.

In people with autoimmune diseases, the immune system turns against and attacks tissues of the body. It is not clear why this happens:

Some people seem to have a tendency to develop autoimmune diseases. Their immune systems are more readily triggered into attacking parts of their own body. In such people, something may trigger the immune system to attack the body's own tissues. The exact trigger is not known. Possible triggers that have been suggested are some kind of infection or some kind of poison (toxin).

There may also be a genetic tendency to develop PBC, as it seems to run in some families.

In people with PBC, the immune system attacks the cells that line the small bile ducts in the liver. This causes inflammation and damage in and around these bile ducts. Gradually they become scarred and may block off.

People with PBC have an increased chance of developing other autoimmune diseases. For example, Sjögren's syndrome, two thyroid diseases called Graves' disease and Hashimoto's thyroiditis, Raynaud's phenomenon and scleroderma.

How common is primary biliary cholangitis?

PBC is an uncommon condition. It affects about 1 in 5,000 people in the UK. 9 out of 10 cases occur in women, who are mainly aged between 30 and 65 years (most commonly between 40

and 60 years). It is most common in the Northern Hemisphere and least common in Australia.

What is the outlook?

Back to contentsPBC is a progressive disease. Most commonly it progresses very slowly over a number of years. Most people have very few problems for twenty years or more.

The outlook is less good for those who already have jaundice at the time of diagnosis, as their disease has already progressed. They are more likely to need liver transplant within five years.

If I have primary biliary cholangitis, what can I do to stay healthy?

Alcohol

If you have primary biliary cholangitis (PBC), you may find that you are no longer able to cope with drinking alcohol. Some people just drink a small amount of alcohol on special occasions. The amount of alcohol that is sensible for you to drink will vary between people and will depend on the degree of damage to your liver.

It is advisable to take particular care around alcohol consumption if you know that you have a developing liver disease like PBC. This does not mean you can never have alcohol, but we know that excessive alcohol consumption reduces health and lifespan even in those who do not have PBC. Your liver is more vulnerable than average, so it makes sense to take particular care of it, even though there are no absolute rules around alcohol.

If you have liver failure or liver scarring (cirrhosis) you should not drink alcohol, as your liver will struggle to process it and it may speed liver failure at this stage.

There is no absolute rule to say that people with PBC, in particular, must give up smoking. However, smoking makes the risk from most diseases worse, and if you want to stay healthier for longer (and be as fit as possible for surgery if you need a liver transplant) then you should not smoke.

Medication

You should always remember to tell a doctor or a pharmacist that you have PBC before you start taking any medication. (This includes any medicines, supplements or remedies that you may buy over the counter.) This is because a lot of medicines are processed in the liver. Because your liver may not be working so well if you have PBC, you may have some unwanted effects from certain medicines.

Fitness, nutrition and diet

Worsening liver disease affects your ability to absorb a balanced diet, and chronic tiredness will reduce your fitness. Doing what you can to counter these two things will help you stay fitter for longer. Your liver is responsible for many aspects of food absorption and processing, so if you don't think about your diet you may become undernourished, particularly if you have lost your appetite, as sometimes occurs.

It is sensible to seek the advice of a dietician to help to ensure a balanced diet, and to assess whether you need food and vitamin supplements, particularly the fat soluble vitamins A, D, E and K. Your levels can be measured and supplements can be taken if needed. A daily multivitamin without iron is safe but added iron should not be taken without medical advice. Smaller, more frequent meals are generally advisable if you are unwell.

Physical activity will help you stay fitter for longer. Being physically active for at least 30 minutes every day of the week is a healthy target. Exercise increases energy levels, reduces body fat, increases muscle mass and helps prevent 'thinning' of the bones (osteoporosis).

Dr Mary Lowth is an author or the original author of this leaflet.

Patient picks for Liver and gallbladder

Digestive health

Gallstones

Gallstones are common but cause no symptoms in two out of three people who have them. They sometimes cause pain, yellowing of your skin or the whites of the eyes (jaundice), inflammation of the pancreas (pancreatitis) and gallbladder inflammation. Surgery is the usual treatment for gallstones that cause symptoms.

by Dr Colin Tidy, MRCGP

Digestive health

Cholecystitis

Cholecystitis is a painful condition caused by an inflamed gallbladder. The most common cause is gallstones.

by Dr Doug McKechnie, MRCGP

Further reading and references

- British Liver Trust

- EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: The diagnosis and management of patients with primary biliary cholangitis; European Association for the Study of the Liver (2017)

- Tanaka A; Current understanding of primary biliary cholangitis. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2021 Jan;27(1):1-21. doi: 10.3350/cmh.2020.0028. Epub 2020 Dec 3.

- Laschtowitz A, de Veer RC, Van der Meer AJ, et al; Diagnosis and treatment of primary biliary cholangitis. United European Gastroenterol J. 2020 Jul;8(6):667-674. doi: 10.1177/2050640620919585. Epub 2020 Apr 16.

- Shen N, Pan J, Miao H, et al; Fibrates for the treatment of pruritus in primary biliary cholangitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Palliat Med. 2021 Jul;10(7):7697-7705. doi: 10.21037/apm-21-1304.

Continue reading below

Article history

The information on this page is written and peer reviewed by qualified clinicians.

Next review due: 30 Oct 2027

31 Oct 2022 | Latest version

Ask, share, connect.

Browse discussions, ask questions, and share experiences across hundreds of health topics.

Feeling unwell?

Assess your symptoms online for free

Sign up to the Patient newsletter

Your weekly dose of clear, trustworthy health advice - written to help you feel informed, confident and in control.

By subscribing you accept our Privacy Policy. You can unsubscribe at any time. We never sell your data.