Endometriosis

Peer reviewed by Dr Colin Tidy, MRCGPLast updated by Dr Toni Hazell, MRCGPLast updated 20 Jun 2024

Meets Patient’s editorial guidelines

- DownloadDownload

- Share

- Language

- Discussion

In this series:Pelvic pain in womenPelvic inflammatory diseaseOvarian cyst

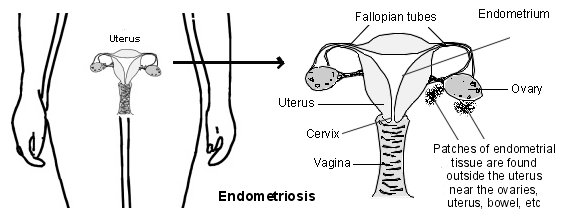

Endometriosis is a condition where tissue similar to the lining of the uterus grows outside the uterus, usually in the pelvic area or lower tummy (abdomen). Its exact cause is unknown, but genetics, hormones, and the immune system may play a role.

It affects those of the female sex, therefore, therefore the words woman/women and the pronouns she/her will be used throughout this leaflet. Endometriosis in trans men is discussed at the end of the leaflet.

In this article:

Key points

Endometriosis is a condition where tissue similar to the lining of the uterus grows outside the uterus, often causing pain, heavy periods, and sometimes fertility problems.

It develops when a person starts their periods and can last up until menopause.

Diagnosis often takes a long time because symptoms are similar to other conditions, such as pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) or fibroids, so multiple tests may be needed.

There is currently no cure for endometriosis. Treatment focuses on pain management through a combination of pain medication, hormonal therapy, and surgery.

What is endometriosis?

Endometriosis is when cells from the womb lining implant and grow in other places outside of the womb (uterus).

Endometriosis

Continue reading below

Endometriosis symptoms

The symptoms of endometriosis vary. Some women experience no symptoms, while others experience mild, moderate or severe symptoms.

Patches of endometriosis can vary from the size of a pinhead to large areas. In general, the bigger the patches of endometriosis, the worse the symptoms. However, this is not always the case. Some women have large patches of endometriosis with no symptoms. Some women have just a few spots of endometriosis but have bad symptoms.

Pain affects different women in different ways and this might be affected by your ethnicity and culture or by any neurodiverse conditions that you have.

More common endometriosis symptoms include:

Painful periods. Also known as menstrual cramping, this pain typically begins a few days before the period and usually lasts the whole of the menstrual cycle. It is different to normal period pain which is usually not as severe and doesn't last as long. Over time, the length of pain may increase until the woman is feeling pain through most or all of the month.

Pain during or after sex. The pain is typically felt deep inside and may last a few hours after sex.

Difficulty becoming pregnant (reduced fertility). This may be due to areas of endometriosis blocking the passage of the egg from an ovary to the Fallopian tube. Sometimes, the reason for reduced fertility is not clear.

Other symptoms include fatigue, pain on bowel movements, pain in the lower abdomen when you pass urine, low back pain and, rarely, blood in the urine or faeces.

Very rarely, patches of endometriosis occur in other sites of the body. This can cause unusual pains or bleeding in parts of the body that occur at the same time as period pains. This could include regular nosebleeds which only occur during the period, or shoulder-tip pain, caused by a patch of endometriosis under the diaphragm.

How common is endometriosis?

The exact number of women who develop endometriosis is not known. This is because many women have endometriosis without symptoms, or with mild symptoms, and are never diagnosed.

It is thought that around 10% of all women of reproductive age in the UK have endometriosis, but if you look at the population of women who are affected by subfertility, this increases to 30-50%. This is because endometriosis is a key cause of subfertility. Endometriosis is the second most common gynaecological condition, with fibroids being the most common.

Endometriosis can affect any woman and symptoms will start after the menarche (the time of the first menstrual period) and before the menopause. A family history of endometriosis in a first degree relative (mother, sister or daughter) increases your risk and use of combined hormonal contraception reduces your risk.

Continue reading below

What causes endometriosis?

There have been several theories for the cause of endometriosis over the years.

The lining of the womb (uterus) is called the endometrium. One theory is that some cells from the endometrium get outside the uterus into the pelvic area. They get there by spilling backwards along the Fallopian tubes when you have a period.

Patches of endometriosis tend to be 'sticky' and may join organs to each other. The medical term for this is adhesions. For example, the bladder or bowel may 'stick' to the uterus. Large patches of endometriosis may form into cysts which bleed each month when you have a period. The cysts can fill with dark blood and are known as 'chocolate cysts'.

Endometriosis diagnosis

If you have symptoms suggestive of endometriosis then the first thing to do is to go and see your GP. They will take a history and may examine you. This will give the GP a good idea as to whether they think that endometriosis is likely.

Tests. Tests in primary care might include swabs and an ultrasound scan.

Swabs will not diagnose endometriosis, but will look for infection in the pelvis. Pelvic infection can cause similar symptoms to endometriosis.

Blood tests are not usually helpful, unless another diagnosis is also being considered.

Women with suspected endometriosis will usually be offered an ultrasound scan of the uterus (womb) and ovaries. This is usually a transvaginal scan, where the scan probe is put into the vagina, as it gives a better view.

However, if you are not happy to have this done, an abdominal ultrasound can be done instead. This is where the probe is put onto the tummy (abdomen). This may be less likely to see subtle signs than a transvaginal scan.

An ultrasound scan can see large areas of endometriosis that have formed a cyst on the ovaries. However, it can't see small areas of endometriosis and it is common for people with endometriosis to have a normal ultrasound scan.

Next steps. After seeing your GP, the next step would be to decide whether you want to be referred to a specialist for a definitive diagnosis, or whether you are happy to be treated in primary care (by your GP) first. The most recent European guidelines say that either approach (refer for a definitive diagnosis, or treat without a diagnosis) are reasonable options for a woman who is suspected to have endometriosis and that this should be discussed with the patient.

Referral. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidance says that referral should be considered if:

The symptoms are severe, persistent or recurring.

The initial management in primary care isn't effective, can't be used or isn't tolerated.

Or, if there are pelvic signs of endometriosis (ie something that a doctor can find on examination of the woman), whether or not deep endometriosis is suspected.

Referral to an endometriosis specialist should also be done if there is a suspicion of endometriosis that is affecting the bowels, bladder, or ureters - the tubes joining the kidneys to the bladder.

Abnormal findings on an ultrasound, for example an ovarian cyst, would also usually prompt referral. The scan will sometimes be repeated in primary care 6-8 weeks after the first scan, to see if the cyst is changing in size.

One reason to consider earlier referral would be if you are trying to conceive, or thinking of doing so soon - most of the treatments used in primary care are also contraceptive and therefore, can't be used in women who want to get pregnant. Also women who have endometriosis may need help to conceive and so early referral is sensible. In some cases, particularly if the wait for a scan and a specialist referral is long, the GP might refer for a scan and to a specialist at the same time, with the intent that the scan will be available by the time that you see the specialist, and its result won't change the decision to refer.

Continue reading below

Endometriosis treatment

Primary Care treatment

If your symptoms are mild and you aren't referred to a specialist for suspected endometriosis, your GP might offer one or more of the following treatments.

Pain relief

Paracetamol taken during periods may be all that you need if symptoms are mild.

Anti-inflammatory painkillers such as ibuprofen, diclofenac, naproxen, and mefenamic acid may be better than paracetamol. However, some people have side-effects with these pain medications, and you should not take them if you have ever had an ulcer in your stomach or small intestine.

Codeine alone, or combined with paracetamol, is a more powerful painkiller. It may be an option if anti-inflammatories don't suit. Constipation is a common side-effect.

To ease pain during periods, it is best to take painkillers regularly over the time of your period rather than only now and then. You can take painkillers in addition to other treatments. Whilst it's not a painkiller, tranexamic acid can be helpful to reduce heavy periods. See our separate feature, 7 tips to help relieve endometriosis pain, for further pain management advice.

Hormone treatments

There are several options. They can be effective, particularly in reducing pain. Some of these also work as contraceptives while you take them, but do not affect future fertility.

Combined oral contraception (CHC) - given as a pill (sometimes called birth control pills), patch or vaginal ring.

Progestogen only contraception - given as a pill, implant or depot injection.

Progestogen hormone tablets. Progestogen hormone tablets include norethisterone, dydrogesterone and medroxyprogesterone - these may not always be contraceptive and so if you don't want to be pregnant, they might not be the best way to treat your symptoms as you will also need contraception; it might be better to use one medication which both treats the endometriosis and provides contraception.

If initial treatment in primary care does not help your symptoms then it may be appropriate to refer to a gynaecologist, often trying another treatment while you are waiting to be seen. You should also be offered support and you might find it helpful to contact organisations such as Endometriosis UK. Whatever path your endometriosis management takes, you should be kept informed at all points.

Overall, the hormone treatment options all have about the same success rate at easing pain. However, some women find one treatment better than others. Also, the treatments have different possible side-effects and not all women can access all treatments. For example, women who have had a blood clot in the past, or have some types of migraine, cannot use CHC.

BSGE endometriosis centres

The British Society for Gynaecological Endoscopy (BSGE) has a list of accredited endometriosis centres.

These will all have a multidisciplinary team which includes:

Surgeons with different expertise, who can work together if endometriosis affects different organs such as the bladder or the bowel.

Psychologist.

Specialist nurse.

Pain specialist.

If you have complicated endometriosis then it would be sensible to be managed at a specialist centre, and in some cases your local hospital might be a specialist centre. However, if you are at the very start of your journey, when endometriosis is suspected but not yet diagnosed, and the nearest specialist centre is a long distance from your home, then it is perfectly reasonable to be referred to your local gynaecologist to start with. A transfer to a specialist centre can always be made later, if needed.

Investigation of suspected endometriosis

If you are referred, the consultant may arrange some specialist tests.

MRI scans

Sometimes a pelvic MRI scan might be done to look for signs of deep endometriosis, such as in the bladder, bowel, or the ureters - the tubes that join the kidneys to the bladder. As with an ultrasound, some types of endometriosis can't be seen on an MRI scan, and a normal MRI scan doesn't rule out endometriosis.

Laparoscopy

The only definitive way to confirm endometriosis is with a laparoscopy. This is a small operation which involves making a small cut, under anaesthetic, in the tummy (abdominal) wall below the tummy button (umbilicus). A thin telescope-like instrument (a laparoscope) is pushed through the skin to look inside.

Patches of endometriosis can be seen by the doctor, and can often be removed at the same time. A laparoscopy is an invasive procedure, and has some risks, but it does have the benefit that the endometriosis can be treated at the same time - this is discussed in more detail later in this leaflet.

If the laparoscopy is negative then it is unlikely that you have endometriosis - another cause for your pain should be considered.

No treatment option

How your endometriosis progresses is very variable. If endometriosis is left untreated, it may improve but may also get worse or stay the same. Endometriosis is not a cancerous condition.

Complications sometimes occur in women with severe untreated endometriosis. For example, large patches of endometriosis can sometimes cause a blockage (obstruction) of the bowel or of the tube (the ureter) from the kidney to the bladder.

If endometriosis symptoms are mild and fertility is not an issue for you then you may not want any treatment. You can always change your mind and opt for endometriosis treatment if symptoms do not go, or become worse.

The main aims of treatment are to improve endometriosis symptoms such as pain and heavy periods and to improve fertility if this is affected.

Endometriosis surgery

Sometimes an operation is advised to confirm the diagnosis of endometriosis and to treat some of the larger patches of endometriosis. An operation may ease symptoms, and increase the chance of pregnancy if infertility is a problem.

There are various techniques that can be used. Most commonly, a thin telescope-like instrument (a laparoscope) is pushed through a small cut in the tummy (abdomen). This is the same procedure that is used to diagnose endometriosis.

The surgeon then uses the laparoscope to see inside the abdomen and remove any cysts or other endometriosis tissue (keyhole surgery).

An alternative to excision (removal of areas of endometriosis) is to use direct heat or a laser to destroy the suspected endometriosis tissue (this is called ablation). During a laparoscopy, the specialist may also be able to remove an ovarian cyst related to endometriosis. These can be very large and are sometimes called 'chocolate cysts' because they are often filled with menstrual fluid that resembles melted chocolate.

Your specialist may therefore ask for your consent at the same time to treat any large patches they may find (as described earlier) 'whilst they are in there'. This saves having two laparoscopies - one to diagnose and one to treat.

Sometimes, but less often, a more traditional operation is done with a larger cut to the abdomen to remove larger endometriosis patches or cysts.

Hysterectomy for endometriosis

If you are certain that you do not want to become pregnant in future, and other endometriosis treatments have not worked well, surgery to remove the uterus - a hysterectomy - may be an option. However, this is major surgery and does not always fully cure endometriosis symptoms, so you should carefully discuss the risks and benefits with your consultant.

The ovaries may also be removed. If your ovaries are not removed then endometriosis is more likely to return. Removing the ovaries causes a permanent early menopause, and you are likely to need hormone replacement therapy (HRT) to treat menopausal symptoms and reduce the risk of osteoporosis (bone thinning).

Most women who have had a hysterectomy need only one hormone (oestrogen) in their HRT, but some women who have had a hysterectomy for endometriosis may need two hormones (oestrogen and progestogen), so make sure that your GP knows that your hysterectomy was for endometriosis.

Other treatments

A specialist endometriosis consultant might also recommend some of the following treatments, which would not generally be started by your GP:

Gonadotrophin-releasing hormone (GnRH) analogues. There are several GnRH analogue preparations which include buserelin, goserelin, nafarelin, leuprorelin and triptorelin. These cause a temporary menopause. Sometimes 'add-back' HRT is given alongside them to reduce menopausal symptoms.

Aromatase inhibitors. For example, letrozole.

Recurrences

Once the endometriosis has gone with treatment, it may come back again in the future. Further treatment or a combination of treatments may need to be considered if symptoms do come back.

Endometriosis in transgender people

Endometriosis can affect anyone who is of the female sex, regardless of their gender identity; this includes trans men and some non-binary people.

Some types of gender-affirming treatment can affect endometriosis symptoms. Trans men may take testosterone as part of hormone therapy. Testosterone often causes periods to become irregular and then eventually stop. This means testosterone should help symptoms of endometriosis.

However, some studies suggest that testosterone therapy doesn't completely shut down the ovaries and womb lining, so some trans men might still have symptoms from endometriosis despite taking testosterone. It would not usually be appropriate for a trans man to take treatment which contains oestrogen (such as the CHC), but they may benefit from a progestogen only pill or a LNG-IUD. It should be noted that testosterone does not provide contraception and so if a trans man is having vaginal sex and does not want to become pregnant, then contraception is needed.

Some trans men have a hysterectomy as part of gender-affirming surgery. A hysterectomy should improve symptoms of endometriosis, but it may not fully cure them for some people. Further surgery - at the time of the hysterectomy or afterwards - may be needed to remove any other areas of endometriosis that are causing symptoms.

If you're trans or non-binary and you have symptoms of endometriosis, speak to your doctor. It's important that your doctor knows that you are a trans man and that you are worried about endometriosis, particularly if you have changed the gender marker on your notes and you didn't know your doctor before you transitioned, otherwise they may not realise that you have female organs and are at risk of endometriosis.

Dr Hazell works for the Royal College of General Practitioners (RCGP) and worked on their eLearning course on endometriosis, which was sponsored by Endometriosis UK, as well as having been involved in other RCGP resources on the subject. She has also written and lectured on endometriosis for a variety of organisations including Livi, RCGP, Haymarket and Cogora.

Frequently asked questions

Can you live normally with endometriosis?

Yes, many people live well with endometriosis, though it can take time to find the right treatment and coping strategies. Managing pain, getting regular medical support, and making small lifestyle adjustments can make a big difference to daily life and overall wellbeing.

Can you get pregnant with endometriosis?

Yes, it’s possible to get pregnant with endometriosis, but it can sometimes make conception more difficult. The condition may affect fertility by causing inflammation or scarring around the reproductive organs. However, many people with endometriosis do go on to have successful pregnancies, either naturally or with treatment.

Is endometriosis genetic?

Endometriosis can run in families, so genetics may increase your risk. If your mother or sister has it, you’re more likely to develop it too, though hormones and other factors also play a part.

Patient picks for Uterine problems

Women's health

Fibroids

A fibroid is a non-cancerous (benign) growth of the womb (uterus). They are also called uterine myomas, fibromyomas or leiomyomas. Their size can vary. Some are the same size as a pea and some can be as big as a melon. Fibroids are common and usually cause no symptoms. However, they can sometimes cause heavy periods, tummy (abdominal) swelling and urinary problems.

by Dr Colin Tidy, MRCGP

Women's health

Endometrial hyperplasia

Endometrial hyperplasia is a thickening of the womb (uterus) lining. The womb lining is called the endometrium. Hyperplasia means over ("hyper" in Latin) growth ("plasia" in Latin).

by Dr Philippa Vincent, MRCGP

Further reading and references

- Endometriosis: diagnosis and management; NICE Guidelines (Sept 2017 - last updated November 2024)

- Endometriosis; NICE CKS, November 2024 (UK access only)

- Becker CM, Bokor A, Heikinheimo O, et al; ESHRE guideline: endometriosis. Hum Reprod Open. 2022 Feb 26;2022(2):hoac009. doi: 10.1093/hropen/hoac009. eCollection 2022.

- Accredited Endometriosis Centres; British Society for Gynaecological Endoscopy Accredited Endometriosis Centres

Continue reading below

Article history

The information on this page is written and peer reviewed by qualified clinicians.

Next review due: 19 Jun 2027

20 Jun 2024 | Latest version

Ask, share, connect.

Browse discussions, ask questions, and share experiences across hundreds of health topics.

Feeling unwell?

Assess your symptoms online for free

Sign up to the Patient newsletter

Your weekly dose of clear, trustworthy health advice - written to help you feel informed, confident and in control.

By subscribing you accept our Privacy Policy. You can unsubscribe at any time. We never sell your data.