Age-related macular degeneration

Peer reviewed by Dr Toni Hazell, MRCGPLast updated by Dr Hayley Willacy, FRCGP Last updated 9 Feb 2026

Meets Patient’s editorial guidelines

- DownloadDownload

- Share

- Language

- Discussion

- Audio Version

Medical Professionals

Professional Reference articles are designed for health professionals to use. They are written by UK doctors and based on research evidence, UK and European Guidelines. You may find the Macular degeneration article more useful, or one of our other health articles.

In this article:

Synonyms: macular degeneration (the term senile macular degeneration is now obsolete)

Continue reading below

What is age-related macular degeneration?

Age-related macular degeneration (AMD, or AMRD) is the term applied to ageing changes without any other obvious precipitating cause that occur in the central area of the retina (macula) in people aged 55 years and older.1

AMD is a progressive chronic disease of the central retina and a leading cause of vision loss worldwide. Most visual loss occurs in the late stages of the disease.2

Pathophysiology34

Back to contentsAMD is characterised by the appearance of drusen in the macula, accompanied by choroidal neovascularisation (wet AMD) or geographic atrophy (dry AMD). The two forms of AMD have differing pathophysiology and progression.

Dry AMD/geographic atrophy (GA)

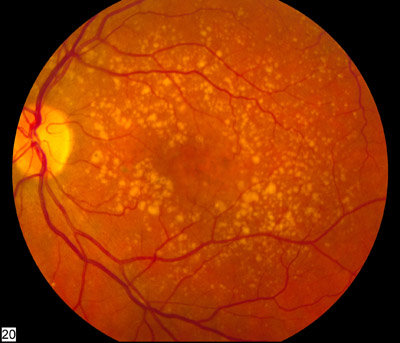

The characteristic lesions of dry AMD are soft drusen and changes in pigmentation (hypopigmentation and/or hyperpigmentation) of the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE). Atrophy of the RPE becomes more extensive with time. The dry form can advance and cause vision loss without turning into the wet form. The end stage of the dry form involves the whole macula becoming affected as the GA evolves.

Dry AMD is the most common form of AMD, occurring in 90% of cases.

Progression to visual loss is usually gradual.

Eventually there is an area of partial or complete atrophy of the RPE. This may or may not involve the fovea.

The formation of drusen is due to the accumulation of lipofuscin (a yellow-brown pigment produced in cells due to the ageing process).

Those with dry AMD have a 4-12% chance per year of developing choroidal neovascularisation (wet AMD). Patients with extremely large drusen have a higher (30%) chance that their AMD will convert to the wet form within five years.5

Wet AMD/neovascular AMD/exudative AMD

In the wet type of AMD, new blood vessels grow in from the choriocapillaris under the retina. They spread under or above the RPE or both. They are fragile and easily leak. Blood vessels don't initially grow under the macula - they start off to the side of the retina and grow towards the centre. For some, it can take only days to grow under the macula; for others it will take weeks. They can reoccur, sometimes many years later. The consequences of abnormal vessel growth are haemorrhage and scar formation (disciform scarring).

Wet AMD accounts for 10% of all cases of AMD but about 60% of advanced cases. Wet AMD is by definition considered advanced at presentation.

Progression varies from a few months to three years. Untreated, most will become severely visually impaired within approximately two years.

The end point of this type of AMD is scar formation known as disciform macular degeneration.

Approximately 50% of patients who have wet AMD in one eye will also develop this condition in their second eye within five years

Continue reading below

Classification of severity

Back to contentsThere are several classification schemes based on the presence and severity of the characteristic features of AMD, namely drusen, pigmentary irregularities, GA and neovascularisation. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) has devised its own scheme as follows:6

AMD classification | Definition |

Normal eyes | No signs of age-related macular degeneration (AMD). Small ('hard') drusen (less than 63 micrometres) only. |

Early AMD | Low risk of progression: Medium drusen (63 micrometres or more and less than 125 micrometres); or Pigmentary abnormalities. Medium risk of progression: Large drusen (125 micrometres or more); or Reticular drusen; or Medium drusen with pigmentary abnormalities. High risk of progression: Large drusen (125 micrometres or more) with pigmentary abnormalities; or Reticular drusen with pigmentary abnormalities; or Vitelliform lesion without significant visual loss (best-corrected acuity better than 6/18); or Atrophy smaller than 175 micrometres and not involving the fovea. |

Late AMD (indeterminate) | Retinal pigment epithelial (RPE) degeneration and dysfunction (presence of degenerative AMD changes with subretinal or intraretinal fluid in the absence of neovascularisation). Serous pigment epithelial detachment (PED) without neovascularisation. |

Late AMD (wet active) | Classic choroidal neovascularisation (CNV). Occult (fibrovascular PED and serous PED with neovascularisation). Mixed (predominantly or minimally classic CNV with occult CNV). Retinal angiomatous proliferation (RAP). Polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy (PCV). |

Late AMD (dry) | Geographic atrophy (in the absence of neovascular AMD). Significant visual loss (6/18 or worse) associated with: Dense or confluent drusen; or Advanced pigmentary changes and/or atrophy; or Vitelliform lesion. |

Late AMD (wet inactive) | Fibrous scar. Sub-foveal atrophy or fibrosis secondary to an RPE tear. Atrophy (absence or thinning of RPE and/or retina). Cystic degeneration (persistent intraretinal fluid or tubulations unresponsive to treatment). NB: eyes may still develop or have a recurrence of late AMD (wet active). |

Idiopathic polypoidal choroidopathy1

This is a variant of AMD, consisting of neovascularisation, primarily located within the choroid. It shares some features with AMD - it involves the macula, it is seen in the same age-group, it shares common non-genetic risk factors, such as smoking and hypertension, and it shares common genetic risk factors.

However, in contrast to AMD, polypoidal choroidopathy is seen in a younger age group than AMD, it more often occurs in the nasal macula and the polypoidal neovascular complexes may leak and bleed but are less likely to invade the retina.

How common is age-related macular degeneration? (Epidemiology) 16

Back to contentsAMD is the most common cause of severe visual impairment in older adults in the developed world.

AMD is responsible for two thirds of registrations of visual impairment in the UK.

The estimated prevalence of AMD in the UK rises with age; 2.4% in those over 50 years of age, 4.8% of those over 65 years of age and 12.2% of those aged 80 years or more. Prevalence is rising with the aging population.

The prevalence in 2020 is estimated to be 645,000 cases of late AMD and 339,000 cases of neovascular AMD (nAMD).

About 90% of all cases have dry AMD.

Wet AMD accounts for about 60% of advanced AMD.

AMD is more common in people of white ethnicity.

Women are more likely than men to develop AMD.

About 67 million people in the EU are currently affected by any AMD. Due to an ageing population, this number is expected to increase by 15% until 2050. For any late AMD, prevalence is expected to increase by 20% to 12 million in the same time period.

Continue reading below

Risk factors3

Back to contentsAMD is a multi-factorial disease; both environmental and genetic components play a role in its development. Several risk factors have been linked to AMD:

Increasing age (the main risk factor).

Smoking: a risk factor both for new-onset AMD and for progression to advanced disease. Risk increases with the number of pack-years. Smoking has a synergistic effect with genetic factors. There also seems to be a relationship between genes and response to treatment.

Family history: several genes are associated with a risk of developing dry AMD. Siblings of affected people have four times greater chance of developing the disease. Concordance for identical twins is 40-100%.

Presence of AMD in one eye greatly increases the risk of it developing in the other: 25-35% will develop visual impairment in the second eye within four years.7 8

All cardiovascular risk factors are also associated with wet AMD.9

Some studies suggest association between AMD and cumulative eye damage from ultraviolet light. People with light-coloured eyes are more likely to develop dry AMD.

People with diets that are high in fat, cholesterol and high-glycaemic index foods, and low in antioxidants and green leafy vegetables, may be more likely to develop AMD.

Obesity (BMI greater than 30) increases risk by about 2.5 times.

Ethnicity affects risk. AMD is very uncommon in native Africans and native Australians. It is most common in white people.

There is growing evidence that a high cumulative lifetime exposure to sunlight also increases the risk of developing AMD.10

Symptoms of age-related macular degeneration (presentation)1 3

Back to contentsAMD causes painless deterioration of central vision, typically in a person aged 55 or more. Patients may initially be asymptomatic and retinal signs may be detected incidentally during a routine eye test.

General symptoms

Reduction in visual acuity, noticed particularly for near vision.

Loss of (or decreased) contrast sensitivity (the ability to discern between different shades).

Size or colour of objects appearing different with each eye.

Abnormal dark adaptation (difficulty adjusting from bright to dim lighting). There may be a central dark patch in the visual field noticed at night, which clears within a few minutes as the eyes adapt.

Photopsia (a perception of flickering or flashing lights).

Light glare.

Visual hallucinations (Charles Bonnet syndrome). These can occur with severe visual loss of any cause. Visual hallucinations are often not reported unless specifically asked about.

Dry AMD symptoms

Visual deterioration tends to be gradual. A common presentation is difficulty with reading, initially with the smallest sizes of print and then later with larger print.

People may not notice visual deterioration when only one eye is affected, so that the visual loss only becomes apparent when the second eye becomes affected.

When GA is bilateral and involves both foveae, patients may complain of deterioration of central vision.

Scotoma - the person may describe a black or grey patch affecting their central field of vision.

Fundus photo of normal left eye

© Medical gallery of Mikael Häggström 2014, via Wikimedia Commons

Normal left eye - medical gallery of Mikael Häggström 2014, via Wikimedia Commons

Dry ARMD fundus image

© Dry ARMD - National Eye Institute of the NIH, via Wikimedia Commons

Dry ARMD - National Eye Institute of the NIH, via Wikimedia Commons

Wet AMD symptoms

The most common symptoms typical of onset of exudative AMD are central visual blurring and distortion. Most patients will complain that straight lines appear crooked or wavy.

Visual deterioration may develop quickly. A person may suddenly become unable to read, drive, or see fine detail such as facial features and expressions.

Vision may suddenly deteriorate to profound central visual loss in the event of a bleed. This may be preceded or accompanied by a shower of floaters.

As for dry AMD, when exudative AMD occurs in the second eye, patients may suddenly become aware of their visual loss.

Examination

Back to contentsExamination may reveal a normal or decreased visual acuity associated with distortion on the Amsler grid. See the separate Examination of the Eye article.

Fundus examination reveals drusen (discrete yellow deposits) in the macular area, which may become paler, larger and confluent in patients progressing to exudative AMD.

Late in the disease, a macular scar may develop, resembling a thick yellow patch over the macular area.

Areas of sharply demarcated hypopigmentation or hyperpigmentation of the peripheral retina are sometimes seen, representing GA of the RPE.

Macular signs of wet AMD include well-demarcated red patches representing intraretinal, subretinal or sub-RPE haemorrhages or fluid. There may be patchy pigmentation.

Differential diagnosis3

Back to contentsPainless loss of vision can be caused by:

Some corneal diseases - eg, Fuch's endothelial dystrophy.

Central serous retinopathy.

Cerebrovascular disease including amaurosis fugax, transient ischaemic attack and stroke.

Some drugs or chemicals including methanol, chloroquine, hydroxychloroquine, isoniazid, thioridazine, isotretinoin, tetracycline or ethambutol.

Pituitary tumour, central nervous system tumour and papilloedema.

Primary open-angle glaucoma (central visual loss occurs late).

Conditions causing similar retinal signs to those observed in AMD include:

Macular degeneration associated with high myopia (greater than −6 dioptres): atrophic or neovascular changes usually occur at a younger age than AMD and have a different natural history and response to treatment.

Rare inflammatory syndromes causing choroidal neovascularisation (for example, ocular histoplasmosis). There are usually signs of active or previous uveitis.

Macular dystrophy - usually inherited and often symmetrical.

Diagnosing age-related macular degeneration (investigations)1 3

Back to contentsSecondary care investigations are aimed at confirming the diagnosis, assessing the extent of the disease and the possibilities for intervention, and keeping a record in order to measure treatment effects and disease progression:

Slit-lamp biomicroscopy to identify drusen and any pigmentary, exudative, haemorrhagic, or atrophic changes affecting the macula (looking for the characteristic area or areas of pallor with sharply defined and scalloped edges). This also helps to detect retinal thickening or elevation due to neovascular AMD.

Colour fundus photography is used to record the appearance of the retina.

Fluorescein angiography is used if neovascular AMD is suspected, in order to confirm the diagnosis and assess the lesions. Fluorescein dye is injected intravenously and photographs of the retina are taken serially to detect abnormal vasculature or leakage from capillaries.

Indocyanine green angiography may be used to visualise the choroidal circulation, which provides additional information to fluorescein angiography.

Ocular coherence tomography produces high-resolution cross-sectional and three-dimensional images of the retina. The guideline from The Royal College of Ophthalmologists states that this test is mandatory for diagnosis and that monitoring response to therapy can reveal areas of GA that may not be clinically visible on biomicroscopy.

Management of suspected age-related macular degeneration3

Back to contentsIf AMD is suspected, refer the person urgently for further assessment, ideally to be seen within one week of referral. Urgent referral is particularly important in people who present with distortion or with rapid-onset visual loss, as these suggest wet AMD.

Refer to one of the following, the choice depending on local referral pathways:

A fast-track macular clinic or medical retina clinic treatment centre.

A local district general hospital eye service.

An optometrist: only an option if they can be seen within one week and the optometrist is able to refer directly to an ophthalmologist.

Advise the person that if there is either a delay of more than one week in being seen by an ophthalmologist or symptoms are worsening whilst they are waiting to be seen, they should attend Eye Casualty as soon as possible, or seek other immediate medical attention to expedite urgent specialist assessment.

Management of dry age-related macular degeneration

Back to contentsThere is no treatment which prevents progression of dry AMD, although lifestyle adjustments may slow progression. Management consists mainly of counselling, smoking cessation, visual rehabilitation and nutritional supplements in those expected to benefit. Co-existing visual impairments such as cataract and refractory error should be appropriately managed (although a Cochrane review found that it is not possible to conclude from the available data whether cataract surgery is beneficial or harmful in people with AMD.)11

There is currently considerable interest in implantable lens systems for end-stage disease (see below).

Advice and support3

People diagnosed with AMD will receive information about their condition from secondary care; however, consider offering information such as:

If the person develops worsening symptoms, or develops symptoms in the second eye, they should either:

Present as soon as possible to Eye Casualty or a similar urgent walk-in hospital eye clinic; or

Present as soon as possible to the GP so that an urgent re-referral can be made to specialised services.

Information about secondary care treatments.

What can be done to slow progression.

Explain that many people with severe sight loss experience visual hallucinations.

Consider registering as sight-impaired. Registration is voluntary but provides access to benefits and help.

If appropriate, information on accessing low vision services (see below).

Signposting to relevant organisations - for example:

The Macular Society provides support and comprehensive information about AMD and living with AMD, in print and audio format.

The Royal National Institute of Blind People provides information and support (including contact details for local support groups) for the visually impaired.

Citizens Advice can provide advice on available benefits.

Driving: many people with AMD are able to drive, depending on the severity of the disease, if their vision fulfils the requirement by the DVLA. It is the person's legal responsibility to check whether their eyesight is good enough to drive.12 Registration for sight impairment or severe sight impairment normally rules out holding a driving licence. If there is uncertainty about fitness to drive, advise the person to contact the DVLA.

Lifestyle advice313 14

Advise smokers to stop smoking: this reduces the risk of AMD progression in people with existing disease.

Encourage the person to eat a healthy, balanced diet rich in leafy green vegetables and fresh fruit: this is likely to improve concentrations of macular pigment in the fundus. There is no firm evidence that this helps to slow the progression of AMD but it is sensible and is unlikely to do any harm.

Patients may be advised by their consultant ophthalmologist to take a dietary supplement. The AREDS trial of 2001 and the follow-up work (AREDS2) concluded that specific dietary supplements may reduce the risk of progression by 25% in these patients. However, the AREDS trial only provides weak evidence of benefit as the post-hoc sub-subgroup analysis showed no difference in vision. Hence, NICE does not recommend AREDS supplements.

A number of studies have looked at using statins and ginkgo biloba extracts (these contain flavonoids and terpenoids which have antioxidant properties) to slow disease progression; however, studies have been inconclusive. These are not treatment options used in the UK.

Visual rehabilitation

This is the mainstay of management for most patients with dry AMD. It revolves around maximising any remaining visual function and assisting the person to maintain an independent life for as long as possible. It may involve:

Refraction check to make sure that any remaining vision is the best it can be.

Low visual aid clinic referral to help the person to make the most of their remaining sight. The services may include: provision and training on the use of optical aids (such as magnifiers) and advice on lighting, tactile aids, electronic aids and other non-optical aids. Low vision services may be provided by social services, community optometrists, eye departments, or the voluntary sector.

A person does not need to be registered as sight impaired to access low vision services. In fact, access to low vision services before the person develops serious visual difficulties gives them the chance to adapt before they are severely affected.

The service may also provide advice on benefits, concessions and support groups for people who are sight impaired. See the separate Severe and partial sight impairment article.

Management of wet age-related macular degeneration

Back to contentsIntravitreal injections of anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (anti-VEGF) agents are the current standard of care. Treatment is carried out by ophthalmologists with a special interest in retinal and macular problems. Interventional treatment takes place either in theatre or in a designated treatment 'clean room' under local anaesthetic. Local anaesthetic eye drops are used to numb the eye before injection. The injection is to the white of the eye and is not visible to the patient.

Anti-VEGF inhibitors1 315

VEGF is a pro-angiogenic growth factor that also stimulates vascular permeability and has a major role in the pathology of neovascular AMD. Since anti-VEGF therapy has become available there has been a substantial improvement in the prognosis of people affected by neovascular AMD:

Anti-VEGF drugs include ranibizumab, bevacizumab, faricimab and aflibercept.

The anti-VEGF drugs are administered by intravitreal injection, usually given 4 weekly but are then generally spaced out to 8-12 weekly depending on response. Treatment and follow-up may be for beyond two years.

Most patients will maintain vision at their current level and about a third will gain some improvement in vision; however, about 10% will not respond to therapy.

Patients should understand the risk associated with intravitreal injections and be instructed to report symptoms suggestive of endophthalmitis without delay.

Pegaptanib is no longer available. Brolucizumab is newly available and NICE recommended for wet AMD although there are concerns about rare cases of inflammation in the eye from it. Ranibizumab, faricimab and aflibercept are recommended if the manufacturer provides it with the discount agreed in the patient access scheme and all of the following circumstances apply in the eye to be treated:

Best-corrected visual acuity is between 6/12 and 6/96 (although the guideline committee advised against the use of strict visual criteria).

No permanent structural damage to the central fovea.

Lesion size is less than or equal to 12 disc areas in greatest linear dimension.

There is evidence of recent presumed disease progression (blood vessel growth, as indicated by fluorescein angiography, or recent visual acuity changes).

It is recommended that treatment with ranibizumab should be continued only in people who maintain adequate response to therapy.

Bevacizumab was developed for systemic treatment of colorectal cancer. It is cheaper, so whilst it is not currently licensed for intraocular use, it is widely used around the world on account of its price. Studies suggest that ranibizumab and bevacizumab have similar efficacy.10 16 In 2017, doctors in the North East were threatened with legal action by the makers of ranibizumab and aflibercept (Bayer and Novartis).17 They claimed it would breach a patient's legal right to an approved drug. However, using bevacizumab would result in significant savings for the NHS, and the CCG argued that pharmaceutical companies: "should not dictate which drugs are available to NHS patients. The choice between three clinically effective drugs should be one for NHS clinicians and patients to make together." In the event, NICE deemed that bevacizumab was as safe and effective as the licensed treatments, and the GMC agreed not to raise concerns over fitness to practise in clinicians who prescribed it.6

Older treatments

These have largely been superseded by anti-angiogenic therapies and are not usually recommended. However, they may have a role for selected people in whom anti-angiogenic drugs are not advisable. They include:

Laser photocoagulation1

Laser photocoagulation could only ever be considered for lesions well away from the fovea because of the risk of severe visual loss arising from a laser scar.

Photodynamic therapy (PDT) with verteporfin6

This involved laser treatment to lesions following intravenous injection of verteporfin, which is selectively taken up by proliferating vascular endothelial cells. The principle of treatment was to destroy the neovascular membrane without damaging the overlying neurosensory retina.

Macular translocation18

The macula is detached with only a small strand of tissue connecting it to the optic disc; the underlying abnormal neovascularisation is removed from the choroid and the macula is re-attached, rotated away from the diseased site. This results in a distorted image (as the macula is in a different position) which is corrected by a further operation to rotate the globe, such that the image is correctly positioned again.

NICE has concluded that there is insufficient evidence to recommend this. A less invasive version involves lifting the macula from the underlying choroid and then folding the sclera so that a healthy piece of choroid is brought to lie under the macula.

Future possibilities

New lines of investigation are looking at neurotrophic growth factors and immunomodulatory drugs.19 20

New therapies for end-stage age-related macular degeneration

Back to contentsImplanted lens systems

This is a relatively new approach to end-stage disease which may help patients with end-stage AMD of either type. A series of lenses (a 'miniature telescope') is used to deflect, focus and enlarge the central visual image on to a functional part of the retina peripheral to the macula. Implantation is usually performed under local anaesthesia.

The brain appears able to adapt, using the healthy part of the retina to view central images. Patients usually require visual rehabilitation.

There is currently insufficient long-term evidence on both efficacy and safety and NICE recommends that this treatment only be carried out in units where there are special arrangements for clinical governance, consent and audit or research.21

Several other intraocular implant devices have been developed. The safety and efficacy of these devices is the subject of ongoing research.22

Complications of age-related macular degeneration

Back to contentsSerous retinal detachment (in exudative AMD only).

Haemorrhage (in exudative AMD only).

Complications of treatment include: 1

Hypersensitivity reaction to a drug.

Severe uncontrolled uveitis.

Ongoing periocular infections.

Thromboembolic phenomena.

Traumatic cataract.

Ongoing visual loss (20% of patients).

The complications of visual impairment include:23

Depression - this occurs in 24-33% of people with AMD and at twice the rate compared with elderly people without AMD.

Visual hallucinations (Charles Bonnet syndrome).

Falls and fractures.

Limitations in mobility, activities of daily living and physical performance.

Reduced quality of life.

Prognosis23 24

Back to contentsAMD is a progressive, irreversible disease affecting central vision only. The process tends to be a slow one in dry AMD, unless concurrent pathology develops in the same or fellow eye, when the decline becomes more apparent.

Early and intermediate AMD is not generally associated with disturbances of central visual function. When vision loss occurs it is usually due to the development of advanced AMD.

For people with early AMD, there is a low risk of progression (1.3%) to advanced AMD after five years in either eye.

For people with intermediate AMD the risk of progression to advanced AMD after five years is about 18%.

Untreated wet AMD leads to significant visual loss (6/60 or worse) within three years.

In dry AMD three lines of visual acuity are lost in 31% of people within two years of diagnosis and in 53% of people within four years.

In untreated wet AMD: the prognosis is poor.

The risk of neovascular AMD developing in the second eye is 12% at one year and 27% at four years.

For people who receive timely treatment for neovascular AMD, there has been a great improvement in prognosis in recent years.

Prevention of age-related macular degeneration25

Back to contentsThe strongest risk factor is age, so currently the most important advice remains to focus on modifiable risk factors, such as control of hypertension, maintaining or achieving an ideal weight and smoking cessation.26

Studies have shown that increased intake of the macular carotenoids lutein and zeaxanthin and foods rich in these nutrients (eg, spinach and collard greens) is associated with a decreased risk of neovascular AMD.14

A risk assessment tool to look at the risk of AMD in an unaffected individual has been developed and is available online. It is intended for use by ophthalmologists.27

Dr Mary Lowth is an author or the original author of this leaflet.

Further reading and references

- Thomas CJ, Mirza RG, Gill MK; Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Med Clin North Am. 2021 May;105(3):473-491. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2021.01.003. Epub 2021 Apr 2.

- Ho AC, Heier JS, Holekamp NM, et al; Real-World Performance of a Self-Operated Home Monitoring System for Early Detection of Neovascular Age-Related Macular Degeneration. J Clin Med. 2021 Mar 25;10(7). pii: jcm10071355. doi: 10.3390/jcm10071355.

- Miller JW, D'Anieri LL, Husain D, et al; Age-Related Macular Degeneration (AMD): A View to the Future. J Clin Med. 2021 Mar 8;10(5). pii: jcm10051124. doi: 10.3390/jcm10051124.

- Brolucizumab for treating wet age-related macular degeneration; NICE technology appraisal guidance, February 2021.

- Faricimab for treating wet age-related macular degeneration; NICE Technology appraisal guidance, June 2022

- Commissioning Guidance: Age Related Macular Degeneration Services, Royal College of Ophthalmologists, May 2024.

- Lim LS, Mitchell P, Seddon JM, et al; Age-related macular degeneration. Lancet. 2012 May 5;379(9827):1728-38. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60282-7.

- Macular degeneration - age-related; NICE CKS, August 2022 (UK access only)

- Ruia S, Kaufman EJ; Macular Degeneration

- Birch DG, Liang FQ; Age-related macular degeneration: a target for nanotechnology derived medicines. Int J Nanomedicine. 2007;2(1):65-77.

- Age-related macular degeneration; NICE Guideline (Jan 2018)

- Roy M, Kaiser-Kupfer M; Second eye involvement in age-related macular degeneration: a four-year prospective study. Eye (Lond). 1990;4 ( Pt 6):813-8.

- Pauleikhoff D, Radermacher M, Spital G, et al; Visual prognosis of second eyes in patients with unilateral late exudative age-related macular degeneration. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2002 Jul;240(7):539-42. Epub 2002 Jun 27.

- Chakravarthy U, Wong TY, Fletcher A, et al; Clinical risk factors for age-related macular degeneration: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Ophthalmol. 2010 Dec 13;10(1):31.

- Chakravarthy U, Evans J, Rosenfeld PJ; Age related macular degeneration. BMJ. 2010 Feb 26;340:c981. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c981.

- Casparis H, Lindsley K, Kuo IC, et al; Surgery for cataracts in people with age-related macular degeneration. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017 Feb 16;2:CD006757. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006757.pub4.

- Assessing fitness to drive: guide for medical professionals; Driver and Vehicle Licensing Agency

- No authors listed; A randomized, placebo-controlled, clinical trial of high-dose supplementation with vitamins C and E and beta carotene for age-related cataract and vision loss: AREDS report no. 9. Arch Ophthalmol. 2001 Oct;119(10):1439-52.

- Chew EY, Clemons T, SanGiovanni JP, et al; The Age-Related Eye Disease Study 2 (AREDS2): study design and baseline characteristics (AREDS2 report number 1). Ophthalmology. 2012 Nov;119(11):2282-9. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.05.027. Epub 2012 Jul 26.

- Pegaptanib and ranibizumab for the treatment of age-related macular degeneration; NICE Technology appraisal guidance, May 2012

- Chakravarthy U, Harding SP, Rogers CA, et al; Alternative treatments to inhibit VEGF in age-related choroidal neovascularisation: 2-year findings of the IVAN randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2013 Jul 18. pii: S0140-6736(13)61501-9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61501-9.

- Cohen D; Are the odds shifting against pharma in the fight for cheaper treatment for macular degeneration? BMJ. 2017 Oct 31;359:j5016. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j5016.

- Macular translocation with 360° retinotomy for wet age related macular degeneration; NICE Interventional Procedure Guidance, May 2010

- Rocco ML, Soligo M, Manni L, et al; Nerve Growth Factor: Early Studies and Recent Clinical Trials. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2018;16(10):1455-1465. doi: 10.2174/1570159X16666180412092859.

- Sandhu HS, Lambert J, Xu Y, et al; Systemic immunosuppression and risk of age-related macular degeneration. PLoS One. 2018 Sep 20;13(9):e0203492. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0203492. eCollection 2018.

- Miniature lens system implantation for advanced age-related macular degeneration; NICE Interventional Procedure Guidance, September 2016

- Grzybowski A, Wang J, Mao F, et al; Intraocular vision-improving devices in age-related macular degeneration. Ann Transl Med. 2020 Nov;8(22):1549. doi: 10.21037/atm-20-5851.

- Hobbs SD, Tripathy K, Pierce K; Wet Age-Related Macular Degeneration (AMD).

- Thomas CJ, Mirza RG, Gill MK; Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Med Clin North Am. 2021 May;105(3):473-491. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2021.01.003. Epub 2021 Apr 2.

- Mathis T, Kodjikian L; Age-Related Macular Degeneration: New Insights in Diagnosis, Treatment, and Prevention. J Clin Med. 2022 Feb 18;11(4):1064. doi: 10.3390/jcm11041064.

- Babaker R, Alzimami L, Al Ameer A, et al; Risk factors for age-related macular degeneration: Updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2025 Feb 21;104(8):e41599. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000041599.

- Klein ML, Francis PJ, Ferris FL 3rd, et al; Risk assessment model for development of advanced age-related macular degeneration. Arch Ophthalmol. 2011 Dec;129(12):1543-50. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2011.216. Epub 2011 Aug 8.

Continue reading below

Article history

The information on this page is written and peer reviewed by qualified clinicians.

Next review due: 8 Feb 2029

9 Feb 2026 | Latest version

Ask, share, connect.

Browse discussions, ask questions, and share experiences across hundreds of health topics.

Feeling unwell?

Assess your symptoms online for free