Chalazion

Peer reviewed by Dr Hayley Willacy, FRCGP Last updated by Dr Colin Tidy, MRCGPLast updated 14 Jun 2022

Meets Patient’s editorial guidelines

- DownloadDownload

- Share

- Language

- Discussion

Medical Professionals

Professional Reference articles are designed for health professionals to use. They are written by UK doctors and based on research evidence, UK and European Guidelines. You may find the Chalazion article more useful, or one of our other health articles.

In this article:

Synonyms: meibomian cyst, tarsal cyst

Continue reading below

What is a chalazion?1

A chalazion, or meibomian cyst, is a focus of granulomatous inflammation in the eyelid arising from a blocked meibomian gland (or tarsal gland).

Meibomian glands are modified sebaceous glands located in the tarsal plates of the upper and lower lids. (The tarsal plates are the two relatively tough elongated pieces of fibrous connective tissue which form the infrastructure of the eyelid.)

There are about 20-25 meibomian glands in each lid, arranged in vertical rows which drain at the lid margin. Their function is to secrete meibum, lipid component of the tear film. Meibum is a complex mixture of lipids which differs significantly from sebum.2 Without it the tear film would evaporate and run off too quickly to protect the eye adequately.

A chalazion is caused by non-infectious drainage occlusion of the gland, causing extravasation of meibum into the eyelid soft tissues. This is followed by a focal secondary inflammatory reaction. Disorders which cause abnormally thick meibum predispose to chalazia, which can therefore be multiple or recurrent.

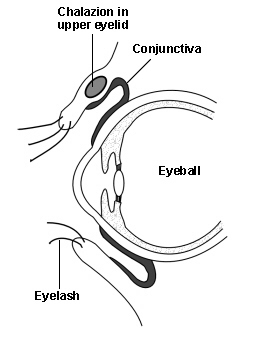

Eye with upper eyelid chalazion

Chalazion is non-infectious, in contrast to internal and external hordeolum. A hordeolum is an acute (usually staphylococcal) infection of the eyelid. There are two types, both of which are (confusingly) known as styes; however, they differ:

Internal hordeolum - when the meibomian gland is infected, resulting in an abscess. This occurs only rarely.

External hordeolum (an acute infection of the lash follicle ± its associated sebaceous gland of Zeiss or Moll). The term 'stye' is often used more specifically to refer to external hordeolum.

For other eyelid problems, see the separate Conditions Affecting the External Eye article.

Chalazion epidemiology

Back to contentsChalazia are the most common of all lid lumps.3

They can occur at any age.

Risk factors include:1

Chronic blepharitis

Rosacea

Seborrhoeic dermatitis

Pregnancy

Diabetes mellitus

Rare associations include:Hyperlipidaemia

Leishmaniasis

Tuberculosis

Immune deficiencies

Viral infections

Continue reading below

Chalazion symptoms1

Back to contentsChalazion

Chalazion presents as a gradually enlarging roundish, firm lesion in either the upper (more common) or the lower lid, usually 2-8 mm in diameter. There may be variability of size from day to day.

It may be a little tender initially as the inflammatory reaction occurs but this settles rapidly and, ultimately, it is painless.

There may be multiple lesions. They can be bilateral. Multiple lesions may look more like a diffuse swelling of the lid.

Everting the lid reveals a discrete, immobile, round, yellowish lump. If the chalazion has grown through the tarsal plate and tarsal conjunctiva, a polypoidal granuloma may form, seen on eversion of the lid. There should be no associated ulceration, bleeding, telangiectasia, tenderness, or discharge.1

Occasionally, a chalazion of the upper lid can press on the cornea, so inducing astigmatism and causing blurred vision.

A chalazion usually drains through the inner surface of the eyelid or is absorbed spontaneously over 2-8 weeks. A large chalazion may indent the cornea, resulting in slightly blurred vision.

Internal hordeolum

This is a tender swelling within the tarsal plate, which progressively enlarges and which may eventually discharge anteriorly (through the skin) or posteriorly (through the conjunctiva).

Diagnosis

Back to contentsDiagnosis is clinical. Distinguishing chalazion from internal and external hordeolum can be difficult.

During the first couple of days the three may be clinically indistinguishable: both conditions initially cause eyelid hyperemia and oedema, swelling and pain: swelling is initially diffuse and can occasionally be dramatic, closing the eye completely.

Chalazion and external hordeolum are common conditions; internal hordeolum is rare.

A chalazion is embedded in the tarsal plate; the overlying skin is freely mobile in the absence of infection. It is not tender to touch, unlike a hordeolum.

Over 1-2 days, chalazion becomes a small non-tender nodule in the eyelid centre, whereas external hordeolum remains painful and localises to an eyelid margin.

Chalazion typically causes yellowish swelling visible on the underside of the eyelid. In external hordeolum, a small yellowish pustule develops at the base of an eyelash, surrounded by hyperemia, induration, and diffuse oedema.

Symptoms of an internal hordeolum are the same as for a chalazion but with more pain, redness and oedema. Inflammation may be severe, sometimes with fever or chills. Spontaneous rupture occasionally occurs, on the conjunctival side.

Continue reading below

Differential diagnosis4

Back to contentsInfections

Internal hordeolum.

External hordeolum.

Early herpes zoster.

Chalazion or hordeolum near the inner canthus of the lower eyelid must be differentiated from dacryocystitis and canaliculitis. Location of maximum induration and tenderness is the eyelid for a chalazion, near the side of the nose for dacryocystitis and over the punctum for canaliculitis.

Chronic chalazia that do not respond to treatment require biopsy to exclude tumor of the eyelid.

Tumours1

Sebaceous gland carcinoma may masquerade as recurrent chalazion.

Merkel's cell tumour (rare).

Lacrimal sac neoplasia (consider this in swellings above the medial canthus).

Investigations

Back to contentsRecurrent or atypical chalazia need histology.

Associated diseases

Back to contentsChalazion treatment and management1

Back to contentsChalazion

Chalazia can resolve spontaneously. The process may be helped by improving the flow of meibomian gland secretions:

Twice-daily (minimum) warm compresses to warm up and loosen secretions. Try cotton pads soaked in warm water, applied for about 10 minutes.

Massage the lids, 'milking' the secretions out (downward movement on the upper lid and upward movement on the lower lid). Do this with clean fingers or cotton buds.

If there is associated blepharitis, finish off by cleaning the lid margin, running the buds along the lid margin, cleaning the orifices. Suggest cotton buds dipped in 9:1 water:baby shampoo solution.

Explain to patients that resolution often takes time and that several weeks of regular hot lid bathing may be required.

A small asymptomatic cyst can be safely left alone. A simple chalazion does not need treatment with antibiotics, even if it is very large.

Some lesions get progressively larger and simple lid hygiene techniques don't help. Consider referring individuals with troublesome lesions to the Eye Unit, where interventions include:

A minor operation, usually under local anaesthetic. The lid is everted and clamped and the cyst is incised. The contents are curetted through the tarsal plate. A short course of ocular chloramphenicol (qds for a week) is prescribed. Follow-up is not usually needed. The lid may remain swollen and bruised for about a week afterwards.

Chalazion may occasionally be managed with a triamcinolone injection alone.6 This is reserved for softer, smaller lesions and is sometimes the preferred option in children. Multiple chalazia can be treated at the same time. The lesion regresses about 1-2 weeks after injection. This treatment is contra-indicated where there is co-existing infection. The success rate is about 75%.

Large or multiple lesions may be treated with both curetting and steroid injection to the base of the curetted area.

Persistent chalazia (particularly those associated with acne rosacea or seborrhoeic dermatitis) may benefit from a course of systemic antibiotics (eg, doxycycline 50 mg od for three months or lymecycline 408 mg od for at least three months).

Lesions that recur at the same site should be biopsied for histology.

Internal hordeolum

There is little evidence for the optimum management of an internal hordeolum.7 Common practice is to treat the acute infection first. Curetting then follows when necessary. Consider a week's course of chloramphenicol ointment (qds) or fucithalmic ointment (bd). Some advocate oral antibiotics for an internal hordeolum.

If there is associated cellulitis (preseptal or orbital), the patient will need oral antibiotics (eg, flucloxacillin 500 mg qds for one week and metronidazole 400 mg tds for one week) and ophthalmic supervision.

Referring

If there is suspicion of associated orbital cellulitis, arrange urgent hospital admission for assessment and management.

If possible malignancy is suspected, arrange urgent referral for specialist assessment, biopsy (where appropriate), and any required management.

If the condition is persistent, recurrent, causing significant astigmatism, cosmetically unacceptable, or there is uncertainty about the diagnosis, refer to an ophthalmologist for further management. An ophthalmologist may consider incision and curettage where appropriate, or intralesional injection of steroid (may be preferred in children). For recurrent lesions, biopsy may be indicated to rule out meibomian gland carcinoma.

A low referral threshold is needed in young children, particularly with large chalazia (there is a risk of amblyopia) or where there is an associated infection.

Complications1

Back to contentsSerious complications are rare. Large chalazia can induce astigmatism by pressing on the cornea (see 'Presentation', above) or cause a mechanical ptosis.

Secondary infection may occur. If the infection spreads to other ocular glands or neighbouring tissues this may lead to periorbital or orbital cellulitis.

Complications of operative removal are rare but may include:

Haemorrhage.

Infection.

(Rarely) canalicular trauma and globe perforation.

The most common problem is recurrence of the chalazion.

Prognosis1

Back to contentsMost resolve either spontaneously or with conservative management, although resolution may take weeks or months. Recurrence is more common in people with risk factors (see above).

Dr Mary Lowth is an author or the original author of this leaflet.

Further reading and references

- Meibomian cyst (chalazion); NICE CKS, April 2024 (UK access only)

- Butovich IA; The Meibomian puzzle: combining pieces together. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2009 Nov;28(6):483-98. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2009.07.002. Epub 2009 Aug 4.

- Adamski WZ, Maciejewski J, Adamska K, et al; The prevalence of various eyelid skin lesions in a single-centre observation study. Postepy Dermatol Alergol. 2021 Oct;38(5):804-807. doi: 10.5114/ada.2020.95652. Epub 2020 Jun 8.

- Carlisle RT, Digiovanni J; Differential Diagnosis of the Swollen Red Eyelid. Am Fam Physician. 2015 Jul 15;92(2):106-12.

- Shields JA, Lally SE, Milman T, et al; Eyelid chalazion or not? Indian J Ophthalmol. 2019 Oct;67(10):1519. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_1620_19.

- Biuk D, Matic S, Barac J, et al; Chalazion management--surgical treatment versus triamcinolon application. Coll Antropol. 2013 Apr;37 Suppl 1:247-50.

- Lindsley K, Nichols JJ, Dickersin K; Non-surgical interventions for acute internal hordeolum. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017 Jan 9;1:CD007742. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007742.pub4.

Continue reading below

Article history

The information on this page is written and peer reviewed by qualified clinicians.

Next review due: 13 Jun 2027

14 Jun 2022 | Latest version

Ask, share, connect.

Browse discussions, ask questions, and share experiences across hundreds of health topics.

Feeling unwell?

Assess your symptoms online for free