Porphyria

Peer reviewed by Dr Colin Tidy, MRCGPLast updated by Dr Hayley Willacy, FRCGP Last updated 21 Aug 2023

Meets Patient’s editorial guidelines

- DownloadDownload

- Share

- Language

- Discussion

- Audio Version

The porphyrias are a group of disorders in which there is a problem with the production of haem (also spelled heme) within the body. Haem is used to make haemoglobin in red blood cells. There are seven different types of porphyria and in most cases they run in families (are inherited).

It is important that the type of porphyria that you have should be identified. This is because each type can have different symptoms and effects on the body.

Symptoms vary greatly and can include tummy (abdominal) pain, nervous system problems, mental health problems and skin problems. You may need to avoid certain things such as some medicines or alcohol that may trigger an attack of porphyria.

In this article:

Video picks for Blood problems

Continue reading below

What are the porphyrias?

The porphyrias are a group of metabolic disorders. A metabolic disorder is the term used when there is a problem with one of the chemical processes within the body. In the porphyrias, the chemical process that is affected is the one that produces a substance called haem.

Haem is mainly made in the liver and in bone marrow. Haem is used to make haemoglobin which transports oxygen around the body in red blood cells. Haem is also used to make a number of proteins in the body, needed for various important functions.

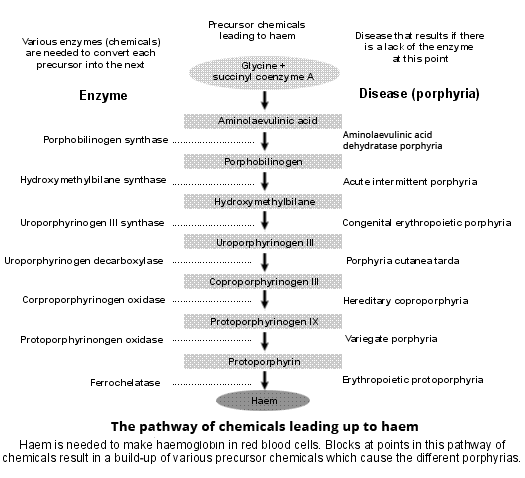

Porphyria-pathway

There is a complex process that goes on in the liver and in bone marrow to make haem. The process has various steps and each step is controlled by a special protein called an enzyme. At each step, substances are made that are known as haem precursors.

These are substances that are made during the process leading up to the making of haem. They include substances called porphyrins. There are seven different types of porphyria. In each type, there is a lack of (or partial lack of) one of the enzymes that controls one of the steps in the making of haem.

Because this enzyme is lacking, there is overproduction of haem precursors including porphyrins. The porphyrins and other precursors may then build up in the body and cause the various problems associated with porphyria.

When porphyrins build up in the skin, it becomes very sensitive to sunlight and this causes the skin symptoms of porphyria. Build-up of other haem precursors in the liver and elsewhere in the body causes the symptoms that occur in the acute attacks of porphyria.

The different types of porphyria

Back to contentsThe porphyrias are a group of diseases and each is named in the diagram above, depending on which enzyme is lacking. However, the porphyrias are also commonly classified according to the effects that they have on the body and the symptoms that they produce. Porphyrias can be:

Acute porphyrias

Symptoms of acute porphyria can vary. The most common symptom is a severe tummy (abdominal) pain. The nervous system is also commonly affected to cause symptoms such as muscle weakness and numbness in parts of the body.

Acute porphyria can also cause mental health (psychiatric) problems including agitation, mania, depression and hallucinations. Symptoms are described more fully later. If there are both nervous system and psychiatric problems these are sometimes put together and called neuropsychiatric problems. The acute porphyrias include:

Acute intermittent porphyria.

Aminolaevulinic acid dehydratase porphyria (also known as plumboporphyria).

Cutaneous porphyrias

This type of porphyria mainly affects the skin. The cutaneous porphyrias include:

Porphyria cutanea tarda.

Erythropoietic protoporphyria.

Congenital erythropoietic porphyria (also known as Günther's disease).

Mixed porphyrias

This type of porphyria can lead to symptoms of both acute porphyria and cutaneous porphyria. They can therefore cause abdominal pain, affect the skin and the nervous system and may also cause psychiatric problems. The mixed porphyrias include:

Variegate porphyria.

Hereditary coproporphyria.

Continue reading below

What causes the porphyrias?

Back to contentsMost types of porphyria are inherited. That is, they are passed on in families through the genes. If you inherit a faulty gene you can develop porphyria. An exception to this is porphyria cutanea tarda. This type of porphyria may sometimes be genetically inherited in families.

However, in many people there may be no family history. In these cases it can be triggered in susceptible people by exposure to certain medicines or chemicals, including oral contraceptives and alcohol (see below for more information).

Most types of inherited porphyria are passed on in families through what is called autosomal dominant inheritance. Briefly, this means that if you have porphyria (and therefore a gene that is faulty), each child that you have has a 50:50 chance of inheriting the faulty gene and also developing the condition.

How common are the porphyrias?

Back to contentsOn the whole, the porphyrias are rare. The diagnosis may be missed because their symptoms are easily confused with other diseases.

Porphyria cutanea tarda is the most common type of porphyria worldwide. It affects about 1 in 25,000 people in the UK. About 1 in 75,000 people have acute porphyria attacks. They may either have one of the acute porphyrias or they may have a mixed porphyria.

Continue reading below

Acute porphyrias

Back to contentsThe most common of these is acute intermittent porphyria. However, the mixed porphyrias (hereditary coproporphyria and variegate porphyria) can also show the same symptoms. Aminolaevulinic acid dehydratase porphyria (also known as plumboporphyria) is very rare.

With this type of porphyria, symptoms tend to come in waves (or as an attack). Between attacks the person is healthy. The frequency and severity of attacks also vary widely between people. It is estimated that at least three quarters of people who inherit an acute porphyria gene will never experience an acute attack of porphyria.

An attack may be brought on (precipitated) by a number of things. These include:

Certain medicines.

Alcohol.

Illicit drug use.

Emotional upset.

Pregnancy.

Periods (menstruation).

Injury.

A surgical procedure.

Sometimes, infection somewhere in the body.

There are certain medicines that you should avoid if you have this type of porphyria. Recommended lists of medicines to avoid are available. Remember that herbal remedies and over-the-counter medicines may also be included in the list of recommended medicines to avoid. Always ask your doctor or pharmacist.

What happens during an acute attack?

The most common age for a first acute attack is anywhere from your late teens to your forties. An attack can go on for one to two weeks. Attacks can often start with anxiety, restlessness and difficulty with sleeping (insomnia).

You may also develop tummy (abdominal) pain which can be severe. Feeling sick (nausea), being sick (vomiting) and constipation can occur.

Nervous system effects can lead to speeding up of your heart rate and an increase in your blood pressure. You may notice that your urine is dark or reddish because your kidneys are trying to get rid of the excessive haem precursors. These are the substances that are made during the process leading up to the making of haem.

Some people can develop muscle weakness during an acute attack. This can affect your arms and legs and sometimes even your chest wall muscles, leading to breathing difficulty. Your sensation may be affected. Rarely, confusion and convulsions can occur.

You may experience mood changes including agitation and/or euphoria and sometimes depression or hallucinations. In some people, these psychiatric problems can continue between attacks.

Rarely, sudden death can occur during an acute attack. This is thought to be due to a disturbance in the electrical activity in your heart (cardiac arrhythmia).

How is this type of porphyria diagnosed?

A test can be done on a sample of your urine to look for porphyrins and related chemicals, to see whether or not you have a porphyria. Further, more detailed tests are then needed to find out which specific type of porphyria you have. This may involve further testing of your urine and sometimes your stools (faeces) and blood.

Note that between attacks, the porphyrin levels in your urine may be normal. If you are found to have a porphyria, other members of your family should also be tested to see if they are affected.

What is the treatment for this type of porphyria?

Often, if you have an acute attack of porphyria like this you need to be admitted to hospital. There are various steps in the treatment of an attack.

Step 1: identify any possible trigger

Ideally, you should try to avoid any possible triggers (examples are given above) in order to reduce your chances of having an attack.

However, if an attack does occur, it is important to try to identify anything that may have triggered the attack this time and to remove the trigger if possible. For example, this may mean stopping a medicine that you are taking.

Step 2: treatment to relieve symptoms

Treatment is then aimed at dealing with any symptoms that may have been caused by the attack. For example, painkillers can be prescribed for abdominal pain and medication can be used to combat nausea and vomiting.

Medication can also be started to reduce any raised heart rate and raised blood pressure or to treat any convulsions that develop.

Step 3: close monitoring for the development of new symptoms

It is important that someone with this type of porphyria be monitored closely for any new symptoms that may develop, such as muscle weakness.

Particular attention needs to be paid to any signs that the muscles of the chest wall start to become weak. This is because your breathing can then become affected. If this happens, you may need help with breathing using a ventilator.

Step 4: treatment to reduce porphyrin build-up

It is usually recommended that a medicine called haem arginate be started early in an attack. This is given directly into a vein (intravenously) and it helps to reduce the overproduction of porphyrins.

Treatment with haem arginate does not usually cause any problems but occasionally it causes inflammation of the veins around the injection site.

Rarely, it may interfere with blood clotting. An allergic reaction to haem arginate is also possible but again is rare. Once-weekly or twice-weekly intravenous treatment with haem arginate has been used in some people to help prevent repeated attacks.

If haem arginate is not available, sugar (glucose), given either by mouth or intravenously, may help to reduce the overproduction of porphyrins and other precursors. This may help to stop an attack.

In people who are severely affected by frequent attacks and where other treatments have not worked, liver transplantation has been carried out successfully.

What is the outlook (prognosis) for this type of porphyria?

It is only a minority of people with porphyria who have repeated acute attacks of porphyria. As mentioned above, some people may never have an attack and some may have one or just a few. Acute attacks can be very severe but they are rarely fatal.

Most people who have one or a few attacks of acute porphyria make a full recovery. They are able to lead a normal life except that they need to be careful to reduce the risk of having another attack by avoiding possible triggers, as discussed above.

Rarely, an acute attack can cause death. If death does occur, it is usually because either the heart stops beating due to a cardiac arrhythmia (as mentioned above) or the breathing muscles are affected, meaning the affected person has to be ventilated. If someone is ventilated for a long time there is then a risk that they may develop pneumonia.

In a small minority of people, long-term (chronic) high blood pressure or chronic kidney disease can develop because of repeated acute attacks. Chronic liver damage can also, rarely, occur.

Cutaneous porphyrias

Back to contentsThis type of porphyria mainly affects the skin, causing skin rashes and other problems. The excess porphyrins that build up can interact with light, making the skin light-sensitive. There are various different types which can produce slightly different symptoms.

Porphyria cutanea tarda

This is the most common of the cutaneous porphyrias.

What are the symptoms?

Symptoms due to this type of porphyria are usually first noticed in your 40s and include:

When your skin is exposed to sunlight, redness and blisters can appear.

Your skin can become quite fragile and can take a long time to heal.

Your skin may be itchy and there may be areas where it is darker (hyperpigmented) or excessively hairy.

The skin on the forehead, cheeks, ears and backs of the hands is most commonly affected but all skin exposed to the sun can be affected. Some people with porphyria cutanea tarda can develop liver damage.

Who gets it?

Porphyria cutanea tarda can be genetically inherited in families. However, in most people affected there is no family history.

In these susceptible people it can be triggered by exposure to certain medicines or chemicals, including oral contraceptives and alcohol. Porphyria cutanea tarda can also sometimes occur if you have another illness, such as:

Chronic active hepatitis.

Again, these conditions are thought somehow to trigger the development of the porphyria. Porphyria cutanea tarda is more common in men than in women.

How is it diagnosed?

As with the acute porphyrias, diagnosis is by measurement of excess porphyrins and other related haem precursors in urine, blood and stool (faeces) samples.

What is the treatment?

Because the skin problems can be triggered by sunlight, one of the main treatments is to avoid exposure to sunlight by covering up and using sunscreens. Avoidance of alcohol and medicines, such as the contraceptive pill, may also be helpful.

A medicine called chloroquine may also help to treat this type of porphyria in some people. This medication makes the excess porphyrins more soluble so that more are passed out (excreted) in the urine.

In some people with porphyria cutanea tarda, there can be a build-up of iron in the body. If this is the case, excess iron can be removed by regularly removing blood, using a procedure called venesection.

The procedure is the same as for blood donors. Every pint of blood removed contains a quarter of a gram of iron. The body then uses some of the excess stored iron to make new red blood cells.

Congenital erythropoietic porphyria

This is a very rare form of porphyria. It is also sometimes known as Günther's disease. Symptoms are usually first noticed in childhood. You may notice that your child's urine appears red in their nappies.

Their skin is also extremely sensitive to sunlight. The skin can become red and develop blisters. These blisters can burst and ulcers can form which may become easily infected. When the skin ulcers heal, there may be scarring of the skin, which is sometimes severe.

Children with this type of porphyria can become anaemic and their spleen can enlarge in size. Possible treatments include a medicine called chloroquine, removal of the spleen (splenectomy) and sometimes a bone marrow transplant.

Erythropoietic protoporphyria

Again, symptoms are usually first noticed in childhood, but they can occur for the first time at any age. There is burning, itching and redness of the skin on exposure to sunlight. In this form of porphyria, blisters do not tend to form and there is minimal scarring of the skin.

Porphyrins and other precursors can build up in the liver and lead to liver failure. Sometimes it can lead to the formation of gallstones.

It is diagnosed by measuring haem precursor levels in red blood cells. Treatment with carotene may be helpful, as it raises tolerance to sunlight. Liver and bone marrow transplantation have also been successfully carried out as other treatments.

Mixed porphyrias

Skin symptoms occur in about half of people with variegate porphyria and about a third of people with hereditary coproporphyria. The skin rash is similar to that in porphyria cutanea tarda (see above).

Sometimes the only symptom of these mixed porphyrias is the skin rash. However, it is important to find out the exact type of porphyria, as those with mixed porphyrias are at risk of developing neuropsychiatric acute attacks as well.

Patient picks for Blood problems

Allergies, blood and immune system

Haemophilia

Haemophilia is a rare bleeding disorder that affects your ability to make a clot. The blood contains substances called clotting factors that work with platelets to form a clot. When you injure yourself the clot stops you bleeding. Haemophilia is a condition where there is a deficiency of clotting factors, so people with this condition usually have prolonged bleeding. There is no cure but with available treatments most people with haemophilia are able to live normal lives.

by Dr Hayley Willacy, FRCGP

Allergies, blood and immune system

Polycythaemia rubra vera

Polycythaemia rubra vera (PRV) is a myeloproliferative disorder, which means the bone marrow makes too many blood cells. It is also sometimes just called polycythaemia (PV). There is an abnormally high number of red blood cells in your blood. You may also have an abnormally high number of platelets and white blood cells.

by Dr Hayley Willacy, FRCGP

Further reading and references

- Cardiff Porphyria Service

- British Porphyria Association

- International Porphyria Network; (Previously European Porphyria Network)

- Stolzel U, Stauch T, Kubisch I; [Porphyria]. Internist (Berl). 2021 Sep;62(9):937-951. doi: 10.1007/s00108-021-01066-1. Epub 2021 Jun 29.

- Phillips JD; Heme biosynthesis and the porphyrias. Mol Genet Metab. 2019 Nov;128(3):164-177. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2019.04.008. Epub 2019 Apr 22.

- Wang B, Bonkovsky HL, Lim JK, et al; AGA Clinical Practice Update on Diagnosis and Management of Acute Hepatic Porphyrias: Expert Review. Gastroenterology. 2023 Mar;164(3):484-491. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2022.11.034. Epub 2023 Jan 13.

Continue reading below

Article history

The information on this page is written and peer reviewed by qualified clinicians.

Next review due: 19 Aug 2028

21 Aug 2023 | Latest version

Ask, share, connect.

Browse discussions, ask questions, and share experiences across hundreds of health topics.

Feeling unwell?

Assess your symptoms online for free

Sign up to the Patient newsletter

Your weekly dose of clear, trustworthy health advice - written to help you feel informed, confident and in control.

By subscribing you accept our Privacy Policy. You can unsubscribe at any time. We never sell your data.