Chronic suppurative otitis media

Peer reviewed by Dr Rosalyn Adleman, MRCGPLast updated by Dr Colin Tidy, MRCGPLast updated 23 Feb 2023

Meets Patient’s editorial guidelines

- DownloadDownload

- Share

- Language

- Discussion

- Audio Version

Medical Professionals

Professional Reference articles are designed for health professionals to use. They are written by UK doctors and based on research evidence, UK and European Guidelines. You may find the Middle ear infection (otitis media) article more useful, or one of our other health articles.

In this article:

Continue reading below

What is chronic suppurative otitis media1

Chronic suppurative otitis media (CSOM) is a chronic inflammation of the middle ear and mastoid cavity. It is predominantly a disease of the developing world. Clinical features are recurrent otorrhoea through a tympanic perforation, with conductive hearing loss of varying severity.

The tympanic membrane is perforated in CSOM. If this is a tubotympanic perforation (in the centre of the tympanic membrane), it is usually 'safe', whilst atticoantral perforation (at the top of the tympanic membrane) is often 'unsafe'. Safe or unsafe depends on the presence of cholesteatoma:

Safe CSOM is CSOM without cholesteatoma. It can be subdivided into active or inactive depending on whether or not infection is present.

Unsafe CSOM involves cholesteatoma. Cholesteatoma is a non-malignant but destructive lesion of the skull base.

CSOM is assumed to be a complication of acute otitis media. The underlying pathology of CSOM is an ongoing cycle of inflammation, ulceration, infection and granulation. A persistent tympanic membrane perforation leads to recurrent middle ear infection and chronic inflammation. CSOM can be caused by bacterial and/or fungal infection (often polymicrobial), including Pseudomonas aeruginosa (most common), Staphylococcus aureus, Proteus spp., Aspergillus spp., Candida albicans. This process may continue, destroying surrounding structures and leading to the various complications of CSOM.

Epidemiology

Back to contentsIn 2004, the World Health Organization estimated the prevalence in the UK to be less than 1%. A more recent systematic review stated that the incidence of CSOM in 2005 in Western Europe was 3.57%.1

Worldwide, there are between 65-330 million people affected, of whom 60% develop significant hearing loss. This burden falls disproportionately on children in developing countries.2

Risk factors3

Multiple episodes of acute otitis media (AOM).

Living in crowded conditions.

Being a member of a large family.

Attending daycare.

Studies of parental education, passive smoking, breastfeeding, socio-economic status and the annual number of upper respiratory tract infections (URTIs) show inconclusive associations only.

Craniofacial abnormalities increase risk: cleft lip or palate, Down's syndrome, cri du chat syndrome, choanal atresia and microcephaly all increase the risk of CSOM.

Continue reading below

Spectrum of otitis media4

Back to contentsOtitis media (OM) is an umbrella term for a group of complex infective and inflammatory conditions affecting the middle ear. All OM involves pathology of the middle ear and middle ear mucosa. OM is a leading cause of healthcare visits worldwide and its complications are important causes of preventable hearing loss, particularly in the developing world.2

There are various subtypes of OM. These include acute otitis media, otitis media with effusion (OME), CSOM, mastoiditis and cholesteatoma. They are generally described as discrete diseases but in reality there is a great degree of overlap between the different types. OM can be seen as a continuum of diseases:

AOM is acute inflammation of the middle ear and may be caused by bacteria or viruses. A subtype of AOM is acute suppurative OM, characterised by the presence of pus in the middle ear. In around 5% of cases the eardrum perforates.

OME is a chronic inflammatory condition without acute inflammation, which often follows a slowly resolving AOM. There is an effusion of glue-like fluid behind an intact tympanic membrane in the absence of signs and symptoms of acute inflammation.

CSOM is long-standing suppurative middle ear inflammation, usually with a persistently perforated tympanic membrane.

Mastoiditis is acute inflammation of the mastoid periosteum and air cells occurring when AOM infection spreads out from the middle ear.

Cholesteatoma occurs when keratinising squamous epithelium (skin) is present in the middle ear as a result of tympanic membrane retraction.

Presentation1

Back to contentsSymptoms

CSOM usually first presents in childhood, often as a spontaneous tympanic perforation following an acute infection of the middle ear.

CSOM presents with a chronically draining ear (otorrhoea), with a possible history of recurrent AOM, traumatic perforation, or insertion of grommets.

The WHO states that otorrhoea for a period of two weeks or more may indicate CSOM, but some experts suggest a duration of more than six weeks of discharge should be used to make the diagnosis.

The otorrhea should occur without otalgia or fever.

Fever, vertigo and otalgia should prompt urgent referral to exclude intratemporal or intracranial complications.

Hearing loss is common in the affected ear. Ask about the impact of this on speech development, school or work. Mixed hearing loss (conductive and sensorineural) suggests extensive disease.

Signs

The external auditory canal may possibly be oedematous but is not usually tender.

The discharge varies from fetid, purulent and cheese-like to clear and serous.

Granulation tissue is often seen in the medial canal or middle ear space.

The middle ear mucosa seen through the perforation may be oedematous or even polypoid, pale, or erythematous.

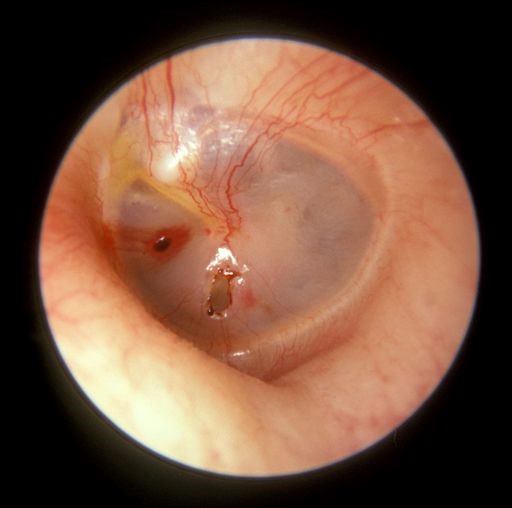

Perforation of the tympanic membrane

© Michael Hawke MD (Own work), CC BY 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

By Michael Hawke MD (Won work), CC BY 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Red flag symptoms which can indicate serious complications (such as mastoiditis and/or intracranial infection) in a person with CSOM include:

Headache.

Nystagmus.

Vertigo.

Fever.

Labyrinthitis.

Facial paralysis.

Swelling/tenderness behind the ear.

The more serious condition of CSOM, with chronic mucous discharge through a large central perforation, can be found under Further Reading and References.

Continue reading below

Differential diagnosis

Back to contentsAcute suppurative otitis media.

Otitis media with effusion.

Otitis externa (inflamed, eczematous canal without a perforation).

Foreign body.

Impacted earwax.

Neoplasm.

NB: chronic serous otitis media is not the same as chronic suppurative otitis media. The former may be defined as a middle ear effusion, without perforation, persisting for more than 1-3 months.

Investigations1

Back to contentsDo not swab the ear in primary care, as the clinical utility of this is uncertain.

An audiogram will normally show conductive hearing loss. Mixed hearing loss may suggest more extensive disease and possible complications.

Imaging studies may be useful:

CT scanning for failed treatment may show occult cholesteatoma, foreign body or malignancy. It may be particularly helpful pre-operatively.5

A fine-cut CT scan can reveal bone erosion from cholesteatoma, ossicular erosion, involvement of petrous apex and subperiosteal abscess.

MRI is better if intratemporal or intracranial complications are suspected. It shows soft tissues better and can reveal dural inflammation, sigmoid sinus thrombosis, labyrinthitis and extradural and intracranial abscesses.

Management1

Back to contentsPrimary care

If CSOM is suspected, refer for ENT assessment and do not swab the ear or initiate treatment.

If a serious complication is suspected - eg, postauricular swelling or tenderness (suggesting mastoiditis), facial paralysis, vertigo or evidence of intracranial infection (see Symptoms and Complications sections of this article), arrange urgent admission or assessment by ENT.

An ENT specialist will be able to microsuction the exudate from the ear canal and hence visualise the tympanic membrane accurately.

Few non-specialists have the equipment or training to carry out aural cleaning.

The topical antibiotics used by specialists are either used off-licence (quinolones) or are not recommended in the presence of tympanic perforation (aminoglycosides).

Patients should be advised to keep the affected ear dry.

Important information |

|---|

Swimming advice |

Secondary care

Conservative treatment of CSOM consists of three components:

An appropriate antibiotic, usually given topically.

Regular intensive aural toilet (microsuction) to remove debris.

Control of granulation tissue.

Medication

Aural toilet and topical antibiotics appear effective at resolving otorrhoea. Long-term outcomes (eg, healing of tympanic perforation, recurrence prevention and hearing improvement) need further study.

Topical treatment is more effective at clearing aural discharge than systemic therapy7 - probably due to the higher local concentrations of antibiotic achieved.

Regarding the use of systemic antibiotics for chronic suppurative otitis media, a Cochrane review found:8

Limited evidence to examine whether systemic antibiotics are effective in achieving resolution of ear discharge for people with CSOM.

When used alone (with or without aural toileting), it was very uncertain whether systemic antibiotics are more effective than placebo or no treatment.

When added to an effective intervention such as topical antibiotics, there seems to be little or no difference in resolution of ear discharge (low-certainty evidence).

Data were only available for certain classes of antibiotics and it is very uncertain whether one class of systemic antibiotic may be more effective than another.

Adverse effects of systemic antibiotics were poorly reported in the studies included. As very sparse evidence was found for their efficacy, the possibility of adverse events may detract from their use for CSOM.

If used, antibiotics should have activity against Gram-negative organisms, particularly pseudomonas and Gram-positive organisms, especially Staphylococcus aureus:

Aminoglycosides and the flouroquinolones both meet these criteria but there remain safety concerns with both. Many authorities advise that topical aminoglycosides should not be used with tympanic perforation, due to their ototoxicity. However, many specialists continue to use them carefully, considering that undertreated OM carries a higher risk of hearing impairment and complications.9

Topical quinolones are effective compared to no drug treatment or topical antiseptics only; however, evidence for their superiority over other topical antibiotics is only indirect.10 UK specialists use either off-licence quinolones or aminoglycosides (because their effectiveness outweighs the risks of ototoxicity). There are specific concerns about the use of flouroquinolones in children because of juvenile animal studies indicating a risk of joint injury in the young. Short-term treatment has been shown to be safe.11 One study did find an association between ciprofloxacin and arthropathy in paediatric patients although the effect was reversible. No link was found between duration of administration and frequency of arthropathy.11

Antibiotic failure is usually due to failure to penetrate the debris rather than to bacterial resistance.

Topical steroids are used to reduce granuloma formation and it is conventional to use combined antibiotic/steroid preparations.

Systemic therapy is reserved for failure to respond to topical therapy. If a focus of infection in the mastoid cannot be reached by topical drops, then systemically administered antibiotics (usually IV) can penetrate in sufficient concentrations to control or eliminate infection. Topical therapy is continued simultaneously. This is usually done in hospital with an accompanying regime of intensive aural toilet.

Treatment should continue for three to four weeks after the end of otorrhoea.

Surgical

There is a paucity of up-to-date evidence of surgical procedures for CSOM.12

However a small case series from India suggested that surgery can usually render an ear 'dry' and hence cured of the CSOM, when other treatments have failed.13

The type of surgery will depend on the severity of the disease process and may involve myringoplasty (repair of the eardrum perforation alone) or tympanoplasty (repair of the eardrum and surgery involving the bones of the inner ear).

If otoscopy reveals granulation tissue of the unsafe variety, aural polyps or infection persisting despite appropriate medical treatment, cholesteatoma should be sought. The goal of ensuing treatment is to create a safe ear, although the appropriate surgical procedure is often controversial.

If cholesteatoma is present (unsafe CSOM), classical radical mastoidectomy, modified radical mastoidectomy or the 'combined approach tympanoplasty' (anterior tympanotomy plus extended mastoidectomy) may be used depending on the extent of cholesteatoma and, more importantly, the experience of the surgeon. Whatever the procedure chosen, the aim of surgery is to remove all disease and to give the patient a dry and functioning ear.

Facial paralysis can occur with or without cholesteatoma. Surgical exploration with mastoidectomy should be undertaken promptly.

Labyrinthitis occurs when infection has spread to the inner ear. Early surgical exploration to remove the infection reduces damage to the labyrinth. Aggressive surgical debridement of the disease (including labyrinthectomy) is undertaken to prevent possibly fatal meningitis or encephalitis.

Where conductive hearing loss has resulted from CSOM (due to perforation of the tympanic membrane and/or disruption in the ossicular chain), surgical removal of the infection and cholesteatoma, followed by ossicular chain reconstruction, will reduce hearing loss.

Cochlear implants have been used in CSOM but it is essential to eradicate all disease first.14

Complications1 15

Back to contentsComplications of CSOM are rare but potentially life-threatening.

Intratemporal complications include:

Intracranial complications include:

Lateral sinus thrombophlebitis.

Sequelae include:

Hearing loss. A population-based observational study demonstrated a high lifetime risk of hearing loss following CSOM in childhood, with up to 91% experiencing at least mild hearing loss.

Risk factors for hearing loss in people with CSOM include:

Diabetes.

Smoking.

Longer duration of disease.

Presence of otorrhoea (active discharge).

Size of the tympanic perforation.

Prognosis3

Back to contentsPrognosis is good in developed countries where there is easy access to antibiotics and surgical treatment. However, in undeveloped countries the outcome can be variable, with significant complications and mortality.

Tympanic membrane perforations can heal spontaneously but can occasionally persist, leading to mild to moderate hearing impairment. If this occurs in the first two years of life, it is associated with an increase in learning disabilities and a decrease in educational performance.

Further reading and references

- Otitis media - chronic suppurative; NICE CKS, July 2022 (UK access only)

- Monasta L, Ronfani L, Marchetti F, et al; Burden of disease caused by otitis media: systematic review and global estimates. PLoS One. 2012;7(4):e36226. Epub 2012 Apr 30.

- Acuin J; Chronic suppurative otitis media. Clin Evid (Online). 2007 Feb 1;2007. pii: 0507.

- Qureishi A, Lee Y, Belfield K, Birchall JP, Daniel M; Update on otitis media – prevention and treatment. Infection and Drug Resistance. 2014;7:15-24. doi:10.2147/IDR.S39637.

- Gerami H, Naghavi E, Wahabi-Moghadam M, et al; Comparison of preoperative computerized tomography scan imaging of temporal bone with the intra-operative findings in patients undergoing mastoidectomy. Saudi Med J. 2009 Jan;30(1):104-8.

- Basu S, Georgalas C, Sen P, et al; Water precautions and ear surgery: evidence and practice in the UK. J Laryngol Otol. 2007 Jan;121(1):9-14. Epub 2006 Nov 14.

- Macfadyen CA, Acuin JM, Gamble C; Systemic antibiotics versus topical treatments for chronically discharging ears with underlying eardrum perforations. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006 Jan 25;(1):CD005608.

- Chong LY, Head K, Webster KE, et al; Systemic antibiotics for chronic suppurative otitis media. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021 Feb 4;2(2):CD013052. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD013052.pub2.

- Llor C, McNulty CA, Butler CC; Ordering and interpreting ear swabs in otitis externa. BMJ. 2014 Sep 1;349:g5259.

- Macfadyen CA, Acuin JM, Gamble C; Topical antibiotics without steroids for chronically discharging ears with underlying eardrum perforations. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005 Oct 19;(4):CD004618.

- Sung L, Manji A, Beyene J, et al; Fluoroquinolones in children with fever and neutropenia: a systematic review of prospective trials. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2012 May;31(5):431-5.

- Mittal R, Lisi CV, Gerring R, et al; Current concepts in the pathogenesis and treatment of chronic suppurative otitis media. J Med Microbiol. 2015 Oct;64(10):1103-16. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.000155. Epub 2015 Aug 5.

- Sengupta A, Anwar T, Ghosh D, et al; A study of surgical management of chronic suppurative otitis media with cholesteatoma and its outcome. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2010 Jun;62(2):171-6. doi: 10.1007/s12070-010-0043-3. Epub 2010 Sep 24.

- Basavaraj S, Shanks M, Sivaji N, et al; Cochlear implantation and management of chronic suppurative otitis media: single stage procedure? Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2005 Oct;262(10):852-5. Epub 2005 Mar 9.

- Yorgancilar E, Yildirim M, Gun R, et al; Complications of chronic suppurative otitis media: a retrospective review. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2012 Jan 15.

- Kim J, Jung GH, Park SY, et al; Facial nerve paralysis due to chronic otitis media: prognosis in restoration of facial function after surgical intervention. Yonsei Med J. 2012 May;53(3):642-8. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2012.53.3.642.

Continue reading below

Article history

The information on this page is written and peer reviewed by qualified clinicians.

Next review due: 22 Feb 2028

23 Feb 2023 | Latest version

Ask, share, connect.

Browse discussions, ask questions, and share experiences across hundreds of health topics.

Feeling unwell?

Assess your symptoms online for free