Gallstones

Peer reviewed by Dr Doug McKechnie, MRCGPLast updated by Dr Colin Tidy, MRCGPLast updated 7 Mar 2025

Meets Patient’s editorial guidelines

- DownloadDownload

- Share

- Language

- Discussion

In this series:CholecystitisAcute pancreatitisERCP

Gallstones are common but cause no symptoms in two out of three people who have them. They sometimes cause pain, yellowing of your skin or the whites of the eyes (jaundice), inflammation of the pancreas (pancreatitis) and gallbladder inflammation. Surgery is the usual treatment for gallstones that cause symptoms.

In this article:

Video picks for Liver and gallbladder

Continue reading below

What are gallstones?

Gallstones form when bile, which is normally fluid, forms stones. Bile is a greenish yellow secretion that is produced in the liver and passed to the gallbladder, where it becomes more concentrated and is either stored or passes via the common bile duct into the first part of the small intestine, the duodenum. There are different types of gallstones:

Cholesterol stones. Gallstones commonly contain lumps of fatty (cholesterol-like) material that has solidified and hardened. The bile contains too much cholesterol. These account for about 9 in 10 of all gallstones.

Pigmented stones. Sometimes bile pigments and calcium deposits form gallstones.

Mixed stones. A combination of both cholesterol and pigmented stones.

Sometimes just a few small stones are formed; sometimes a great many. Occasionally, just one large stone is formed.

Human gallstones

© George Chernilevsky, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

By George Chernilevsky, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

About one in eight people develop gallstones at some stage in their lives. Gallstones are 2-3 times more common in women than in men. Gallstones become more common with increasing age.

Gallstones are more common if you are female, particularly if you have had children. Gallstones are more likely if you have recently lost weight (from either dieting or weight loss surgery). Other risk factors for gallstones include obesity and a family history of gallstones.

You are more likely to develop gallstones if you have Crohn's disease, liver cirrhosis or diabetes. Certain blood disorders such as sickle cell anaemia also increase the risk of developing gallstones.

Taking certain medicines such as the contraceptive pill and hormone replacement therapy also increase the risk of gallstones.

You can find out more about the gallbladder and bile in the Understanding the gallbladder and bile section below.

Symptoms of gallstones

Back to contentsAbout 4 in 5 of all people with gallstones do not develop any symptoms and do not know they have them. It is common to have stones in the gallbladder that cause no symptoms. Gallstones are often found when the tummy (abdomen) is scanned or X-rayed for other reasons.

About one out of five people with gallstones develop symptoms or problems. Symptoms are more likely to develop in smokers and women who have had a lot of children. Symptoms include:

Biliary colic. This is a severe pain in the upper abdomen. Gallstone pain is usually worst to the right-hand side, just below the ribs. It is caused by a stone that becomes stuck in the cystic duct. This is the small tube that takes bile from the gallbladder to the bile duct. The gallbladder then squeezes (contracts) hard to dislodge the stone and this causes pain. The pain eases and goes if the gallstone is pushed out into the bile duct (and then usually out into the gut), or if it falls back into the gallbladder.

Pain from biliary colic can last just a few minutes but, more commonly, lasts for several hours. A severe pain may only happen once in your lifetime, or it may flare up from time to time. Sometimes less severe but niggly pains occur now and then, particularly after a fatty meal when the gallbladder contracts most.Inflammation of the gallbladder. This is called cholecystitis. This can lead to infection in the gallbladder. Symptoms usually develop quickly and include abdominal pain, high temperature (fever) and being generally unwell. You will normally be admitted to hospital and have your gallbladder removed soon if you develop this problem. See the separate leaflet called Cholecystitis which provides more details.

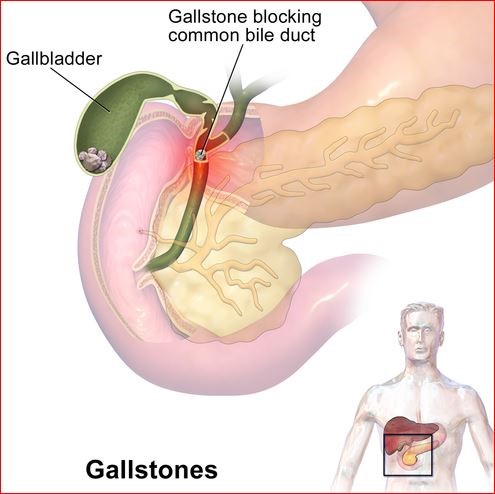

Jaundice. This is an uncommon complication of gallstones. It occurs if a gallstone comes out of the gallbladder but causes blockage of the bile ducts. Bile then cannot pass into the gut and so seeps into the bloodstream. This causes yellowing of your skin or the whites of the eyes (jaundice). The stone may eventually be passed into the gut. However, it is common to need an operation to remove a gallstone which has become stuck in the bile duct. (Note: there are many other causes of jaundice apart from gallstones.) See the separate leaflet called Jaundice which provides more details.

Blockage illustration

© BruceBlaus, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

By BruceBlaus, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Pancreatitis. This is an inflammation of the pancreas. The pancreas makes a fluid rich in enzymes (chemicals which digest food). The pancreatic fluid travels down the pancreatic duct. The pancreatic duct and bile duct join together just before opening into the first part of the gut (small intestine) known as the duodenum. If a gallstone becomes stuck here it can cause pancreatitis which is a painful and serious condition. See the separate leaflet called Acute pancreatitis which provides more details.

Gallbladder abscess (empyema of the gallbladder).

Infection of the bile ducts (acute cholangitis).

Cancer of the gallbladder is more common in people with gallstones but it is not known why there is a link. However, gallbladder cancer is still rare, even in people who have gallstones.

Gallstone ileus is a very rare cause of bowel obstruction, and occurs when a gallstone blocks the small intestine.

See the separate article called Could it be gallstones?

Continue reading below

How are gallstones diagnosed?

Back to contentsIn many cases your symptoms, combined with tenderness in the upper right side of your tummy (abdomen), will alert the doctor that this is likely to be gallstones. However, tests are sometimes needed to rule out other conditions such as stomach ulcers, irritable bowel syndrome, liver disease and tumours. An ultrasound scan and blood tests are the most common investigations done. Other investigations including different types of scans may sometimes be required.

Gallstones treatment

Back to contentsNo treatment is needed in most cases. It is often best to leave gallstones alone if they cause few or no symptoms. If symptoms are problematic after fatty food, it makes sense to avoid that type of food. For more details, see the leaflet called Gallstones diet sheet.

Medication. Once gallstones start giving symptoms, surgery is the best treatment. However, you may be given painkillers and antibiotic medication if the gallbladder becomes infected. Surgery is performed once the infection settles down - usually a week later.

Surgery. An operation to remove the gallbladder is the usual treatment if you have troublesome symptoms caused by gallstones. Different techniques to remove the gallbladder may be recommended depending on its site, size and other factors.

Keyhole surgery is now the most common way to remove a gallbladder. The medical term for this operation is laparoscopic cholecystectomy. It is called keyhole surgery, as only small cuts are needed in the tummy (abdomen) with small scars remaining afterwards. The operation is done with the aid of a special telescope that is pushed into the abdomen through one small cut. This allows the surgeon to see the gallbladder. Instruments pushed through another small cut are used to cut out and remove the gallbladder. Keyhole surgery to remove the gallbladder is not suitable for all people.

A few people with gallstones need a traditional operation to remove the gallbladder. This is called cholecystectomy. In this operation a larger cut is needed to get at the gallbladder.

Other surgical procedures may be needed if a stone becomes stuck in the bile duct.

Laser treatment to break up bile duct stones. A procedure called laser lithotripsy can be used to break up stones in the bile duct.

This is usually carried out under general anaesthetic using endoscopy - a flexible telescope inserted through the mouth. A laser fibre is inserted gently through the flexible telescope and used to break the stones into smaller pieces, which can be more easily removed.

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommends that it should only be considered for difficult-to-treat bile duct stones, with special arrangements for monitoring. This is because it has been found to be effective, but at the moment there is limited evidence about its long-term safety.

You can find out more about this procedure, and NICE's recommendations, from the further reading section at the end of this leaflet.

Continue reading below

After a gallbladder is removed

Back to contentsYou do not need a gallbladder to digest food. Bile still flows from the liver to the gut once the gallbladder is removed. However, there is no longer any storage area for bile between meals. The flow of bile is therefore constant, without the surges of bile that occur from a gallbladder when you eat a meal.

You can usually eat a normal diet without any problems after your gallbladder is removed, although some patients are advised to eat a low-fat diet. Up to half of people who have had their gallbladder removed have some mild tummy (abdominal) pain or bloating from time to time. This may be more noticeable after eating a fatty meal. Some people notice an increase in the frequency of passing stools (faeces) after their gallbladder is removed. This is like mild diarrhoea. It can be treated by antidiarrhoeal medication if it becomes troublesome.

Post-cholecystectomy syndrome

Back to contentsWhilst it is unusual to have problems following gallbladder removal, some patients develop problems including tummy (abdominal) pain, yellowing of their skin or the whites of the eyes (jaundice) or indigestion symptoms.

Understanding the gallbladder and bile

Back to contentsBile is a fluid made in the liver. Bile contains various substances, including bile pigments, bile salts, cholesterol and lecithin. Bile is passed into tiny tubes called bile ducts. The bile ducts join together (like the branches of a tree) to form the main bile duct. Bile constantly drips down the bile ducts, into the main bile duct and then into the gut.

The gallbladder lies under the liver on the right side of the upper tummy (abdomen). It is like a pouch which comes off the main bile duct and fills with bile. It is a 'reservoir' which stores bile. The gallbladder squeezes (contracts) when we eat. This empties the stored bile back into the main bile duct. The bile passes along the remainder of the bile duct into the first part of the gut, known as the duodenum.

Bile helps to digest food, particularly fatty foods.

Common questions

Back to contentsCan gallstones make you tired and dizzy?

Gallstones themselves don't cause dizziness and tiredness. However, dizziness and tiredness may occur during an attack of biliary colic or when complications develop, such as during episodes of cholecystitis.

Foods to avoid with gallstones?

You should avoid eating too many foods with a high saturated fat content. You should also maintain a diet with adequate fibre. See the leaflet on Healthy eating for further information.

How do you get gallstones?

Gallstones are thought to be caused by an imbalance in the chemicals in bile. Gallstones can form if there are high levels of cholesterol or bilirubin in the bile. This can cause tiny crystals to develop. The crystals can grow slowly into solid stones that can be as small as a grain of sand or as large as a pebble. Sometimes only one stone will form, but there are often several gallstones at the same time.

What do gallstones look like in the toilet?

A gallstone may be too small to notice, but a larger gallstone often looks like a tiny pebble. The shape might look jagged rather than smooth. Most are yellow, but some are brown.

Can gallstones kill you?

Gallstones are harmless in themselves but a small number of people with gallstones may develop serious problems if the gallstones block a bile duct or move into another part of the bowel (gut). These complications are much more dangerous and include cholecystitis, gallbladder abscess (empyema of the gallbladder), infection of the bile ducts (acute cholangitis), acute pancreatitis, cancer of the gallbladder, and gallstone ileus.

What are gallstones made of?

There are three main types of gallstone, which are cholesterol stones, bile pigment stones and gallstones that are a mixture of cholesterol and bile pigment. Cholesterol stones are typically yellow-green in colour, while pigment stones are darker (because of the bilirubin in pigment stones).

Where is gallstones pain felt?

Gallstones often don't cause any symptoms. But gallstones may cause sudden, severe upper abdominal pain, either in the middle (just below the breastbone) or on the right side (just below the right side of the ribcage). The pain usually lasts for longer than 30 minutes and up to 8 hours. Pain on the right side of your upper abdomen may radiate to your side or shoulder blade. After an episode of pain, it may be several weeks or months before you have another episode.

Can gallstones cause back pain?

Gallstone typically cause pain in the upper tummy (abdomen) just below the middle or right side of your ribcage. However, back pain between your shoulder blades or pain in your right shoulder may also be caused by gallstones.

Do gallstones cause diarrhoea?

Back to contentsDiarrhoea is not a common symptom of gallstones but if gallstones block a bile duct or move into the pancreas or gut (bowel) then the gallstones may cause diarrhoea.

Patient picks for Liver and gallbladder

Digestive health

Primary sclerosing cholangitis

Primary sclerosing cholangitis is an uncommon condition affecting the bile ducts and liver. Inflammation and scarring of the bile ducts can lead to liver damage and cirrhosis - a condition where normal liver tissue is replaced by scar tissue (fibrosis). Different treatments are available to control symptoms that may develop and also to manage any complications which may occur. The outlook for people with primary sclerosing cholangitis can be very variable.

by Dr Colin Tidy, MRCGP

Digestive health

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) describes a range of conditions caused by a build-up of fat within liver cells.

by Dr Doug McKechnie, MRCGP

Further reading and references

- Gallstone disease; NICE Clinical Guideline (October 2014)

- Gallstones; NICE CKS, June 2024 (UK access only)

- Cholecystitis - acute; NICE CKS, July 2021 (UK access only)

- Laser lithotripsy for difficult-to-treat bile duct stones; NICE Interventional procedures guidance, June 2021

- EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines on the prevention, diagnosis and treatment of gallstones; European Association for the Study of the Liver (2016)

- Gutt C, Schlafer S, Lammert F; The Treatment of Gallstone Disease. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2020 Feb 28;117(9):148-158. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2020.0148.

Continue reading below

Article history

The information on this page is written and peer reviewed by qualified clinicians.

Next review due: 6 Mar 2028

7 Mar 2025 | Latest version

Ask, share, connect.

Browse discussions, ask questions, and share experiences across hundreds of health topics.

Feeling unwell?

Assess your symptoms online for free

Sign up to the Patient newsletter

Your weekly dose of clear, trustworthy health advice - written to help you feel informed, confident and in control.

By subscribing you accept our Privacy Policy. You can unsubscribe at any time. We never sell your data.