Meniscal tears

Knee cartilage injuries

Peer reviewed by Dr Hayley Willacy, FRCGP Last updated by Dr Colin Tidy, MRCGPLast updated 10 Feb 2023

Meets Patient’s editorial guidelines

- DownloadDownload

- Share

- Language

- Discussion

In this series:Sports injuriesHamstring injuryGroin strainAnkle injurySprains and strainsKnee ligament injuries

You've all seen the footballer on TV - one moment they're running full pelt, the next they've tripped over another player and are clutching their knee in agony. There's a good chance an injury to their knee cartilage is at least part of the problem.

In this article:

For some people, the symptoms of meniscal injury go away on their own after a few weeks. However, for other people the symptoms persist long-term, or flare up from time to time, until the tear is treated.

Continue reading below

What are the symptoms of damaged articular cartilage?

It is much less common to damage your articular cartilage than it is to damage your meniscal cartilage (a meniscal tear). If you do injure your articular cartilage, it is very likely that you have also injured another part of your knee at the same time, such as one of the ligaments or your meniscus.

The symptoms that you get from any other injury may be more noticeable than the symptoms that are being caused by the injury to the articular cartilage.

Articular cartilage does not contain any nerves or blood vessels but you may still feel pain from a damaged articular cartilage. If it is painful, the pain tends to be felt around the joint line and on movement.

'Locking' of the knee can occur if a piece of cartilage affects the smooth movement of the knee.

The knee may swell and it may be painful to weight bear.

The knee joint

Back to contentsCross-section diagram of the knee

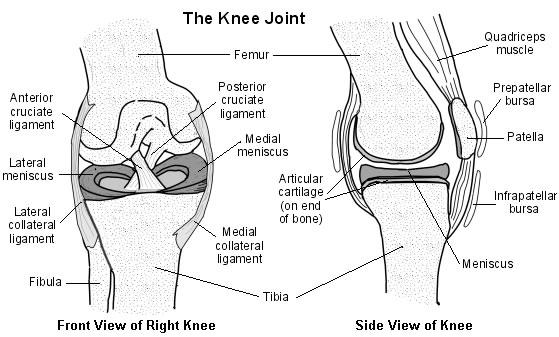

There are four bones around the area of the knee joint: the thigh bone (femur), the main shinbone (tibia), the outer shinbone (fibula) and the kneecap (patella). The main movements of the knee joint are between the femur, the tibia and the patella. Tough connective tissue (articular cartilage) covers the ends of the tibia and femur and the back of the patella around the knee joint. The articular cartilage reduces friction between the bones of the knee joint and helps smooth movement between them.

Each knee joint also contains an inner and outer meniscus (a medial and lateral meniscus). The menisci (plural of meniscus) are thick rubbery pads of cartilage tissue. They are C-shaped and become thinner towards the middle of the joint. The meniscal cartilages sit on top of, and are in addition to, the usual thin layer of articular cartilage which covers the top of the tibia. The menisci act like shock absorbers to absorb the impact of the upper leg on the lower leg. They also help to make the knee movements smooth and help to make the knee stable.

When people talk about a cartilage injury to a knee, they usually mean an injury to one of the menisci. However, the knee also has tough connective tissue covering the ends of the bones in the joint - this is called articular cartilage - and damage can occur here as well. The areas of articular cartilage can be seen in the side view of the knee joint in the diagram above.

Continue reading below

How do you tear your meniscal cartilage?

Back to contentsThe knee is commonly injured in sports, especially rugby, football and skiing. You may tear a meniscus by a forceful knee movement whilst you are weight bearing on the same leg. The typical injury is for a footballer to twist (rotate) the knee whilst the foot is still on the ground - for example, whilst dribbling around a defender.

Another example is a tennis player who twists to hit a ball hard but with the foot remaining in the same position. The meniscus tears fully or partially. How serious the injury is depends on how much is torn and the exact site of the tear.

Meniscal tears may also occur without a sudden severe injury. In some cases a tear develops due to repeated small injuries to the cartilage or to wear and tear (degeneration) of the meniscal cartilage in older people. In severe injuries, other parts of the knee may also be damaged in addition to a meniscal tear. For example, you may also sprain or tear a ligament.

Meniscal cartilage does not heal very well once it is torn. This is mainly because it does not have a good blood supply. The outer edge of each meniscus has some blood vessels but the area in the centre has no direct blood supply. This means that although some small outer tears may heal in time, larger tears, or a tear in the middle, tend not to heal.

How do you injure the articular cartilage?

Back to contentsDamage to the cartilage covering the end of the bones at the knee joint is called a chondral injury. If the underlying bone itself is also damaged, this is called an osteochondral injury.

Injuries to the articular cartilage usually happen in combination with other injuries to the knee, either to the meniscus (as above) or the knee ligaments or bones.

Continue reading below

How is a meniscal tear diagnosed?

Back to contentsHow you injured your knee and the symptoms you are getting may be enough to tell a doctor that you have a meniscal tear.

A doctor or therapist will need to examine your knee. Certain features of the examination may point towards a meniscal tear. They will also want to examine the rest of your leg, including your hip, to check for other injuries or other causes of your symptoms.

Cartilage doesn't show up well on an X-ray so an X-ray of your knee is not usually necessary. The one time you might need to have an X-ray would be if your doctor is concerned that you might have damaged your bone (rather than cartilage) when you injured your knee.

Knee ultrasound is limited compared with ultrasound for other joints because the cruciate ligaments and knee cartilages are usually difficult to see properly.

The diagnosis of a meniscal tear can be confirmed by a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan.

Computerised tomography (CT) scanning is not as good as an MRI for diagnosing a meniscal tear.

How is damage to the articular cartilage diagnosed?

Back to contentsJust as when someone injures their meniscal cartilage, the history of how you injured your knee is important. Examination of the knee may reveal a swelling of the joint (effusion), a 'crunching' of the joint (crepitus) or locking but these things can be caused by other conditions too. X-rays are sometimes useful but an MRI scan provides doctors with the best pictures of the articular cartilages of the knee.

Damage to your articular cartilage may be found on an MRI scan when you are having the scan for another reason. Your doctor may have requested the scan to investigate other injuries to your knee, such as a meniscal tear or a ligament injury.

Can I treat a knee cartilage injury myself?

Back to contentsFor the first 48-72 hours think of:

PRICE - Protect, Rest, Ice, Compression, Elevation; and

Do no HARM - no Heat, Alcohol, Running or Massage.

PRICE:

Protect your injured knee from further injury.

Rest your affected knee for 48-72 hours following injury. Consider the use of crutches to keep the weight off your injured knee. However, many doctors say that you should actually not keep your injured knee immobile for too long. You can usually start some exercises to help keep your knee joint moving and mobile. Start these as soon as you can tolerate the exercises without them causing too much pain. You can ask your doctor when you can start to move your knee joint and what exercises you should do.

Ice should be applied as soon as possible after your knee injury - for 10-30 minutes. Less than 10 minutes has little effect. More than 30 minutes may damage the skin. Make an ice-pack by wrapping ice cubes in a plastic bag or towel. (Do not put ice directly next to skin, as it may cause ice-burn.) A bag of frozen peas is an alternative. Gently press the ice-pack on to your injured knee. The cold from the ice is thought to reduce blood flow to the damaged ligament. This may limit pain and inflammation. After the first application, some doctors recommend reapplying for 15 minutes every two hours (during daytime) for the first 48-72 hours. Do not leave ice on while asleep.

Compression with a bandage will limit swelling and will help to rest your knee joint. A tubular compression bandage can be used. Mild pressure that is not uncomfortable or too tight and does not stop blood flow is ideal. A pharmacist will advise on the correct size. Remove before going to sleep. You may be advised to remove the bandage for good after 48 hours. This is because the bandage may limit movement of the joint which should normally be moving more freely after this time. However, bandages of the knee are sometimes kept on for longer to help keep swelling down and to keep the affected knee more comfortable. Ask your health professional what is best in your case.

Elevation aims to limit and reduce any swelling. For example, keep your foot on the affected side up on a chair with a pillow under your knee when you are sitting. It may be easier to lie on a sofa and to put your foot on some cushions. When you are in bed, put your foot on a pillow. The aim is that your affected knee should be above the level of your heart.

R is sometimes added to this list to make PRICER. R stands for Rehabilitation which is the most important part of the treatment for meniscal tears - to get you and your knee back to normal. You may need to see a physiotherapist or sports therapist for advice about exercises to do to strengthen and stretch the muscles around your knee if your symptoms persist.

(Note: despite the common guidance of putting an ice-pack on injuries, there is some evidence from animal studies that it can delay healing and some researchers in the field suggest the evidence base for putting ice on an injury should currently be thought of as equivocal.)

Avoid HARM for 72 hours after injury. That is, avoid:

Heat - for example, hot baths, saunas, heat packs. Heat has the opposite effect to ice on the blood flow. That is, it encourages blood flow. So, heat should be avoided when inflammation is developing. However, after about 72 hours, no further inflammation is likely to develop and heat may then be soothing.

Alcoholic drinks, which can increase bleeding and swelling and decrease healing.

Running or any other form of exercise which may cause further damage.

Massage, which may increase bleeding and swelling. However, as with heat, after about 72 hours, gentle massage may be soothing.

What medication will help?

Back to contentsParacetamol and codeine

Paracetamol is useful to ease pain. It is best to take paracetamol regularly, for a few days or so, rather than every now and then. An adult dose is two 500 mg tablets, four times a day. If the pain is more severe, you may be prescribed codeine, which is more powerful but can make some people drowsy and constipated.

Anti-inflammatory painkillers

These medicines are also called non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). They relieve pain and may also limit inflammation and swelling. There are many types and brands. You can buy some (for example, aspirin and ibuprofen) at pharmacies, without a prescription. You need a prescription for others.

Side-effects sometimes occur with anti-inflammatory painkillers. Stomach pain, and bleeding from the stomach, are the most serious. Some people with asthma, high blood pressure, kidney failure, bad indigestion and heart failure may not be able to take anti-inflammatory painkillers. So, check with your doctor or pharmacist before taking them in order to make sure they are suitable for you.

But note: The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) Clinical Knowledge Summaries (CKS), a well-known source of guidance for doctors in the UK, do not recommend that anti-inflammatory painkillers be used in the first 48 hours after the injury. This is because of concerns that they may delay healing. The logic is that some inflammation is a necessary part of the healing process. So, it may be that decreasing inflammation too much by taking these medicines may impair the healing process. This is a supposed (theoretical) concern, as no trials have proved this point. Further research is needed to clarify the use of these medicines following an injury. Also, if you are having surgery to repair a torn ACL (see below), it is thought that, theoretically, NSAIDs may not be a good idea to take for a long period of time after the surgery because they may have an effect on the success of the surgery.

Rub-on (topical) anti-inflammatory painkillers

There are various types and brands of topical anti-inflammatory painkillers. You can buy some, without a prescription, at pharmacies. You need a prescription for the others. There is debate as to how effective rub-on anti-inflammatory painkillers are compared with tablets. Some studies suggest that they may be as good as tablets for treating sprains. Some studies suggest they may not be as good. However, the amount of the medication that gets into the bloodstream is much less than with tablets and there is less risk of side-effects.

Further treatment

Back to contentsThis will then depend on:

The severity of symptoms.

How any persisting symptoms are affecting your life.

Your age.

Your general health.

When will you need physiotherapy for a meniscal tear and why?

Back to contentsSmall tears may heal by themselves in time, usually over about six weeks. You may be advised to see a physiotherapist or sports therapist to advise you on how to strengthen the supporting structures of your knee, such as the quadriceps and hamstring muscles. Some tears don't heal but, even so, they may not cause long-term symptoms once the initial pain and swelling has settled, or cause only intermittent or mild symptoms. In these cases, no further treatment will be needed.

If you are having symptoms which interfere with your ability to work or which have been going on for more than 6-8 weeks, despite rehabilitation with a physiotherapist, a referral to an orthopaedic surgeon is advised. However, it is important to realise that if you have been diagnosed with a meniscal tear, even if it has shown up on an MRI scan, this doesn't mean you will have to have surgery.

If you do need surgery to your knee, you will be advised to have physiotherapy afterwards. This is so as to keep the knee joint active (which encourages healing) and to strengthen the surrounding muscles to give support and strength to the knee.

When will you need physiotherapy for an articular cartilage injury and why?

Back to contentsAdvice from a physiotherapist can be particularly useful if you have been diagnosed with an articular cartilage injury. Moving the knee passively (which means moving it without using the surrounding muscles) may help the articular cartilage to heal. Moving the knee passively also helps to reduce the formation of scar tissue.

What operations are done for a meniscal tear?

Back to contentsIf the tear causes persistent troublesome symptoms, particularly painful locking, then an operation may be advised - although evidence for the benefit of surgery is variable. Several studies have been done that suggest that surgical treatment for people who have a meniscal tear due to wear and tear (degeneration) is no better than following a standard exercise regime.

Most operations are done by arthroscopy (see below). The types of operations which may be considered include the following:

The torn meniscus may be able to be repaired and stitched back into place. However, in many cases this is not possible.

In some cases where repair is not possible, a small portion of the meniscus may be trimmed or cut out to even up the surface.

Sometimes, the entire meniscus is removed but this is rarely done as long-term results are not good.

Meniscal transplants have recently been introduced. The missing meniscal cartilage is replaced with donor tissue, which is screened and sterilised much in the same way as for other donor tissues such as for kidney transplants. These are more commonly performed in America than in Europe.

There is a new operation in which collagen meniscal implants are inserted. The implants are made from a natural substance and allow your cells to grow into it so that the missing meniscal tissue regrows. It is not yet known whether this is any better than other treatments.

What operations are done for damage to the articular cartilage?

Back to contentsThe treatment of large injuries or those which cause persistent symptoms is by surgery. Surgery may involve a keyhole operation (arthroscopy - see below) to remove loose bits of cartilage or to transplant cartilage into the damaged area. Another method used to repair damaged knee cartilage is to make tiny holes (called microfractures) in the bone beneath the damaged cartilage. This releases bone marrow into the damaged cartilage. The bone marrow then helps to repair the cartilage. Unfortunately, the newly formed tissue can break down over time and long-term results may be disappointing. You may want to discuss the pros and cons of surgery and the type of surgery with your doctor.

If damaged articular cartilage that is bad enough to cause symptoms is left untreated, this may lead to early osteoarthritis.

What is an arthroscopy?

Back to contentsThis is a procedure that allows a surgeon to look inside a joint by using an arthroscope. An arthroscope is like a thin telescope with a light source. It is used to light up and magnify the structures inside a joint. Two or three small (less than 1 cm) cuts are made at the front of the knee. The knee joint is filled up with fluid and the arthroscope is introduced into the knee. Probes and specially designed tiny tools and instruments can then be introduced into the knee through the other small cuts. These instruments are used to cut, trim, take samples (biopsies), grab, etc, inside the joint. Arthroscopy can be used to treat meniscal tears and damaged articular cartilage. There are some risks from arthroscopy. See the separate leaflet called Arthroscopy and Arthroscopic Surgery for more details.

Following surgery, you will have physiotherapy to keep the knee joint active (which encourages healing) and to strengthen the surrounding muscles to give support and strength to the knee.

Patient picks for Sports injuries

Bones, joints and muscles

Knee ligament injuries

Knee ligaments are the short bands of strong but flexible tissue that hold the knee together while allowing movement of the knee joint. Sometimes one or more of the knee ligaments can become injured, such as when playing sport or as a result of a car accident.

by Dr Colin Tidy, MRCGP

Bones, joints and muscles

Hamstring injury

A hamstring injury is a strain (tear) to one or more of the three large muscles at the back of the thigh (or their tendons at the back of the knee or in the pelvis).

by Dr Toni Hazell, MRCGP

Further reading and references

- Bhan K; Meniscal Tears: Current Understanding, Diagnosis, and Management. Cureus. 2020 Jun 13;12(6):e8590. doi: 10.7759/cureus.8590.

- Beaufils P, Pujol N; Management of traumatic meniscal tear and degenerative meniscal lesions. Save the meniscus. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2017 Dec;103(8S):S237-S244. doi: 10.1016/j.otsr.2017.08.003. Epub 2017 Sep 2.

- Stein JM, Yayac M, Conte EJ, et al; Treatment Outcomes of Meniscal Root Tears: A Systematic Review. Arthrosc Sports Med Rehabil. 2020 Apr 28;2(3):e251-e261. doi: 10.1016/j.asmr.2020.02.005. eCollection 2020 Jun.

- Karia M, Ghaly Y, Al-Hadithy N, et al; Current concepts in the techniques, indications and outcomes of meniscal repairs. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2019 Apr;29(3):509-520. doi: 10.1007/s00590-018-2317-5. Epub 2018 Oct 29.

Continue reading below

Article history

The information on this page is written and peer reviewed by qualified clinicians.

Next review due: 9 Feb 2028

10 Feb 2023 | Latest version

Ask, share, connect.

Browse discussions, ask questions, and share experiences across hundreds of health topics.

Feeling unwell?

Assess your symptoms online for free

Sign up to the Patient newsletter

Your weekly dose of clear, trustworthy health advice - written to help you feel informed, confident and in control.

By subscribing you accept our Privacy Policy. You can unsubscribe at any time. We never sell your data.