Knee pain

Peer reviewed by Dr Laurence KnottLast updated by Dr Colin Tidy, MRCGPLast updated 16 Feb 2022

Meets Patient’s editorial guidelines

- DownloadDownload

- Share

- Language

- Discussion

Medical Professionals

Professional Reference articles are designed for health professionals to use. They are written by UK doctors and based on research evidence, UK and European Guidelines. You may find the Knee and kneecap pain article more useful, or one of our other health articles.

In this article:

Knee pain affects approximately 25% of adults, and its prevalence has increased by almost 65% over the past 20 years. Initial assessment should focus on excluding urgent causes while considering the need for referral1 .

A good history and knee examination are essential to determine if a significant knee injury has occurred. A good knee assessment will guide further investigations and/or treatment. If there is little or nothing abnormal to find despite the history, examine the hip and lumbar spine. Referred pain from the hip as a cause of knee pain is common, especially in children.

Continue reading below

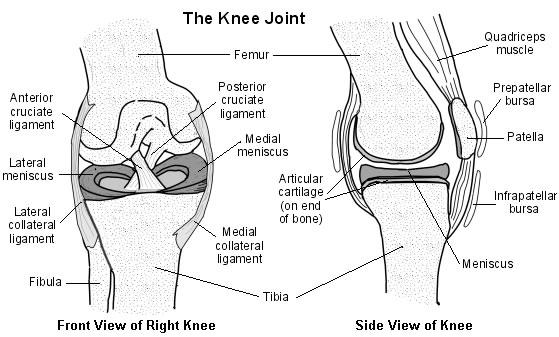

Anatomy of the knee

Joints - there are two joints in the knee:

Patellofemoral joint.

Tibiofemoral joint (the joint that is usually referred to as 'the knee joint').

Patella - the patellar tendon (also called patellar ligament) passes anteriorly to the patella. The medial retinaculum also gives support to the patella.

Ligaments - stability of the tibiofemoral joint is provided by various ligaments:

Anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) - controls rotational movement and prevents forward movement of the tibia in relation to the femur. Runs between attachments on the front (hence, anterior cruciate) of the tibial plateau and the posterolateral aspect of the intercondylar notch of the femur.

Posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) - prevents forward sliding of the femur in relation to the tibial plateau. Runs between attachments on the posterior part (hence, posterior cruciate) of the tibial plateau and the medial aspect of the intercondylar notch of the femur.

Medial collateral ligament (MCL) - prevents lateral movement of the tibia on the femur when valgus (away from the midline) stress is placed on the knee. Runs between the medial epicondyle of the femur and the anteromedial aspect of the tibia. Also has a deep attachment to the medial meniscus.

Lateral collateral ligament (LCL) - prevents medial movement of the tibia on the femur when varus (towards the midline) stress is placed on the knee. Runs between the lateral epicondyle of the femur and head of the fibula.

Menisci - the medial and lateral menisci are located within the knee joint, attached to the tibial plateau. They help to protect the articular surfaces by absorbing some of the forces transmitted through the knee. They also help to stabilise and lubricate the knee.

Cross-section diagram of the knee

History2

Knee pain (see 'Causes of knee pain', below): nature, speed of onset.

A 'popping' or 'snapping' sound may suggest rupture of a ligament.

Swelling: rapid swelling (0-2 hours) suggests haemarthrosis which may, for example, be due to fracture, ACL or PCL rupture, and patellar dislocation. Gradual swelling (6-24 hours) suggests an effusion which may be due to meniscal injury. Swelling over a 24-hour period, with no history of trauma, could be due to septic arthritis or an inflammatory arthritis. See also the separate Knees That Swell article.

Locking or clicking suggests a loose body and may be due to meniscal injury.

The knee giving way suggests instability (eg, ACL injury) or muscle weakness.

Fever, although not always present, suggests septic arthritis.

Night pain or pain at rest is suggestive of bone tumour. Ask about weight loss.

Knee pain which is worse at rest and stiffness on waking that lasts more than 30 minutes suggest inflammatory polyarthritis.

Also ask about problems with any other joints, including the back, previous history of knee injury, other past medical history, occupation and level of exercise.

Continue reading below

Causes of knee pain2

Acute knee injury

Knee cartilage injuries: medial or meniscal injury.

Knee ligament injuries: MCL, LCL, PCL, ACL. See also:

Leg fractures and dislocations: knee fractures and dislocations, distal femoral fractures, proximal tibial and fibular fractures.

Patellar tendon rupture.

Global knee pain

Monoarthritis.

Polyarthritis: osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis.

Crystal arthropathies: gout, pseudogout.

Seronegative arthropathies - eg, ankylosing spondylitis, reactive arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, Behçet's disease, juvenile idiopathic arthritis.

Infective causes: septic arthritis, osteomyelitis.

Disease of bone around the knee: osteosarcoma - usually affects children. The most common sites are around the knee or proximal humerus. The most frequent presenting symptom of osteosarcoma is pain, especially with activity. See the separate Bone Tumours article.

Referred pain (usually from the hip).

Rare causes - eg, haemochromatosis, rheumatic fever, spontaneous haemarthrosis (may occur in coagulation disorders, especially haemophilia), familial Mediterranean fever.

Anterior knee pain

See also the separate Anterior Knee Pain article.

Common causes of anterior knee pain include:

Patellofemoral pain syndrome: the term 'anterior knee pain' is sometimes used synonymously with 'patellofemoral pain syndrome' (previously referred to as chondromalacia patellae) but it is important to make a careful assessment of the underlying cause in order to ensure appropriate management and advice.

Fat pad impingement: the infrapatellar fat pad (Hoffa's pad) is impinged between the patella and the femoral condyle. This is thought to be due to a direct blow to the knee, but no trauma may be recalled. Treatment includes patellar taping to relieve impingement.

Patellofemoral misalignment (patellofemoral instability/recurrent patellar subluxation): this is more common in young females - patellar hypermobility with apprehension and pain when the patella is pushed laterally are found on examination.

Other causes include:

Referred pain from the hip - eg, slipped upper (capital) femoral epiphysis, Perthes' disease.

Patellar stress fracture.

Osgood-Schlatter disease and Sinding-Larsen Johansson disease. Both are a cause of knee pain that is worse when jumping and running.

Lateral knee pain

Common causes of lateral knee pain include:

Iliotibial band syndrome3 :

An overuse injury caused by repeated flexion and extension of the knee. Occurs due to friction between the iliotibial band and the underlying lateral epicondyle of the femur. It produces lateral knee pain in cyclists, dancers, runners, football players and military recruits; it is the most common running injury to cause lateral knee pain.

There is tenderness over the lateral epicondyle of the femur 1-2 cm above the lateral joint line. Flexion/extension of the knee can reproduce symptoms.

Weakness in the hip adductors is presumed to be a major aetiological factor.

While massage and stretching may give short-term relief, treatment requires correction of predisposing factors and altering the biomechanics with muscle strengthening. Changing shoes and running surface may also help.

There is a paucity of good-quality research to guide management.

Steroid injection and surgery are not indicated.

Lateral meniscus problem (tear, degeneration, cyst).

Other causes include: common peroneal nerve injury, patellofemoral pain syndrome, osteoarthritis, referred pain from the hip or the lumbar spine.

Medial knee pain

Common causes of medial knee pain include:

Patellofemoral pain syndrome (see 'Anterior knee pain', above).

Medial meniscus problem (tear, degeneration, cyst).

Pes anserinus bursitis and/or tendinopathy.

Other causes include: tumour, referred pain from the hip or the lumbar spine, MCL injury, osteoarthritis.

Posterior knee pain

Common causes of posterior knee pain include:

Knee joint effusion.

Referred pain from the lumbar spine or patellofemoral joint.

Other causes include: Baker's cyst, deep vein thrombosis, peripheral vascular disease, PCL injury, gastrocnemius and hamstring insertion injuries.

Examination

Examination of gait

Always remember to watch the patient both standing and walking.

Ask the patient to lie comfortably on a couch. Pain or apprehension will make examination difficult. Always examine and compare both knees.

Inspection

Look at the patient: an unwell, pyrexial patient may have septic arthritis.

Look at the joint: with a view to establishing if it is swollen, red, or hot.

Examine for muscle wasting: compare with the other side.

Examine for an effusion

This is unnecessary if swelling is gross.

The massage (bulge) test: with the knee in extension, use the palm of your hand to massage any fluid in the anteromedial compartment of the knee into the suprapatellar pouch. Next, stroke the lateral side of the joint and the lateral side of the suprapatellar pouch. This will push any fluid present back into the anteromedial compartment. Look for a fluid impulse.

Eliciting a patellar tap: extend the knee and empty the suprapatellar pouch by applying pressure from the palm of your hand above the knee. This will push fluid underneath the patella, lifting it. Maintain this pressure. Next, press down on the patella with the fingers of the other hand and the patella will be felt to move down and touch ('tap') the underlying bone if an effusion is present.

Examine for tenderness

Palpation should include:

The medial and lateral joint line - palpate with the knee in 30° flexion.

The patellofemoral joint.

The MCL and the LCL.

The popliteal fossa. This may be easier with the patient supine. Consider Baker's cyst, deep vein thrombosis, gastrocnemius pathology, popliteal artery aneurysm4 .

Examine range of knee movement

Examine active and passive flexion and extension.

The examining hand on the kneecap may detect crepitus. This is of limited value as it is commonly found in both osteoarthritis and patellofemoral pain syndrome.

Full range of movement is from 3° of hyperextension to 140° of flexion4 . For most activities of daily living 115° of flexion is needed4 .

Always compare both knees.

Fixed flexion deformities can be due to torn cartilage or loose body.

Examine stability

MCL and LCL

The valgus and varus stress tests - can be used2 :

Flex the knee by 30°.

Hold the ankle firmly between your arm and your side.

With your other hand putting pressure above the knee, attempt to adduct and abduct the knee joint.

More than minimal movement is abnormal.

ACL

Lachman's test:

Flex the knee to 15-20°.

Hold the lower thigh in one hand and the upper tibia in the other.

Push the thigh in one direction and pull the tibia in the other.

Reverse the direction, pushing the tibia and pulling the thigh and look for increased movement or laxity between the tibia and the femur.

The anterior drawer test - less sensitive than the Lachman's test due to need to ensure that the hamstring muscles are relaxed:

Flex the knee to 90°.

Hold the position by sitting on the patient's foot.

With both hands, grasp below the knee and pull the tibia forward.

Compare the degree of movement with the other side.

Excessive movement may indicate ACL disruption.

Pivot shift test: this test is difficult to perform and is generally not recommended for use by GPs2 :

Hold the patient's heel with one hand.

Internally rotate the foot and the tibia and, at the same time, apply an abduction (valgus) force at the knee.

Flex the knee from 0° to 30° whilst applying this force and still holding the foot and tibia in internal rotation.

Try to detect any palpable or visible reduction between the femur and the tibia.

PCL

Posterior drawer test:

Perform the same examination as the anterior drawer test but pushing backwards in relation to the tibia instead of pulling forwards.

Compare the degree of movement with the other side.

Posterior sag test:

Flex both knees to 90°.

Look at the position of the tibia in relation to the femur.

If there is rupture of the PCL, the position will be relatively posterior.

Other tests

McMurray's test for meniscal injury - this test is no longer recommended because the diagnostic accuracy is low and it is thought that it may exacerbate the injury2 :

Flex the patient's hip and knee to 90°.

Hold the heel with the right hand and steady the knee with the left.

Slowly extend the knee, using the right hand and, at the same time, palpate the joint line with the left hand. Perform this with the tibia in external and then internal rotation at the various stages of flexion.

A positive test is evident when a 'clunk' is felt with associated pain.

Patellar apprehension test to assess stability of the patella:

The patient should be lying on their back with the knee extended.

Apply pressure to the medial side of the patella.

Keep this pressure applied whilst passively flexing the knee to 30°.

Look for any lateral patellar movement and any 'apprehension' from the patient.

Continue reading below

Investigations

Knee joint aspiration can be both diagnostic and therapeutic. See the separate Joint Injection and Aspiration article.

X-ray may reveal fracture of any of the bones, erosive disease, calcium pyrophosphate crystals of pseudogout or joint space narrowing.

Damage to cartilage or ligaments can be demonstrated by MRI:

The Direct Access Magnetic resonance imaging: Assessment for Suspect Knees (DAMASK) trial looked at the influence of early access to MRI of the knee, compared with referral to an orthopaedic specialist, on GPs' diagnoses and treatment plans for people with knee problems. The trial found that access to MRI did not significantly alter their diagnoses or treatment plans but it did significantly increase their confidence in these decisions5 .

There is a significant false positive rate from MRI of the knee. Abnormal findings have been reported in healthy individuals with no knee symptoms: 16% have evidence of meniscal tears, increasing to 36% for people aged over 456 .

Further reading and references

- Bunt CW, Jonas CE, Chang JG; Knee Pain in Adults and Adolescents: The Initial Evaluation. Am Fam Physician. 2018 Nov 1;98(9):576-585.

- Knee pain - assessment; NICE CKS, Aug 2022 (UK access only)

- van der Worp MP, van der Horst N, de Wijer A, et al; Iliotibial band syndrome in runners: a systematic review. Sports Med. 2012 Nov 1;42(11):969-92. doi: 10.2165/11635400-000000000-00000.

- Examination of the knee; Wheeless' Textbook of Orthopaedics

- Brealey SD; Influence of magnetic resonance of the knee on GPs' decisions: a randomised trial. Br J Gen Pract. 2007 Aug;57(541):622-9.

- Crawford R, Walley G, Bridgman S, et al; Magnetic resonance imaging versus arthroscopy in the diagnosis of knee pathology, concentrating on meniscal lesions and ACL tears: a systematic review. Br Med Bull. 2007;84:5-23. Epub 2007 Sep 3.

Continue reading below

Article history

The information on this page is written and peer reviewed by qualified clinicians.

Next review due: 15 Feb 2027

16 Feb 2022 | Latest version

Ask, share, connect.

Browse discussions, ask questions, and share experiences across hundreds of health topics.

Feeling unwell?

Assess your symptoms online for free