Gastroparesis

Peer reviewed by Dr Toni Hazell, MRCGPLast updated by Dr Philippa Vincent, MRCGPLast updated 12 Jan 2025

Meets Patient’s editorial guidelines

- DownloadDownload

- Share

- Language

- Discussion

- Audio Version

Gastroparesis is now more commonly known as delayed gastric emptying. It is a chronic condition in which food passes through the stomach and into the gut (intestine) more slowly than usual. The nerves that usually trigger the stomach muscles to move food out of the stomach and into the intestine don't work as effectively as normal. This is not caused by an obstruction or structural abnormality but by a failure of the normal mechanisms.

In this article:

Video picks for Other digestive conditions

Continue reading below

What is gastroparesis?

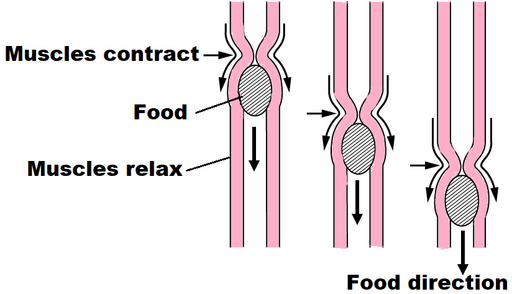

Gastroparesis, or delayed gastric emptying, is a condition where the movement of solid food from the stomach into the small intestine is slower than normal. This is due to a mechanical disorder where the muscles which normally push the food through via peristalsis do not work effectively. It is thought that this is due to the nerves which supplies them not working normally.

Peristalsis

© OpenStax College, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

OpenStax College, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

It is not clear how common gastroparesis is. Recent studies suggest that approximately 13 per 100, 000 people may be affected.

Gastroparesis can affect people of all ages but it is more common in older age groups and also more common in women.

Gastroparesis symptoms

Back to contentsGastroparesis symptoms vary from mild to severe and often tend to come and go. Many people with mild gastroparesis are not aware of any symptoms.

Usually a number of symptoms occur together rather than having just one symptom. The symptoms of gastroparesis may include:

Feeling full earlier than normal during a meal (early satiety) and being unable to finish a meal.

Feeling sick (nausea). Vomiting undigested food eaten a few hours earlier.

Belching.

Heartburn. This can occur due to the stomach emptying slowly.

Gastroparesis symptoms are sometimes very similar to other conditions such as indigestion (dyspepsia), food intolerance, stomach acid reflux, cyclical vomiting syndrome, chronic pancreatitis, and other causes of nausea and vomiting.

Continue reading below

Gastroparesis causes

Back to contentsIdiopathic gastroparesis. For many people with gastroparesis, there's no obvious cause. This is called idiopathic gastroparesis - this appears to be the most common cause in the UK. However, smoking and chronic alcohol use are commonly associated with idiopathic gastroparesis. Cannabis has also been shown to delay gastric emptying.

Diabetic gastroparesis. The most common cause is diabetes, especially poorly controlled diabetes. Over time, diabetes can cause damage to the stomach nerves. This is called diabetic gastroparesis. About 57 in 100 cases in the United States are due to diabetes although this number is lower in the UK. Gastroparesis can occur in type 1 diabetes or type 2 diabetes.

Gastroparesis may also occur:

Post-surgical. After some types of surgery - particularly weight loss surgery or surgery to the oesophagus, stomach or bowel - gastroparesis can occur.

Medicines. Drug-induced gastroparesis accounts for about 12 in 100 cases of gastroparesis. This can occur as a result of various medications including strong painkillers (opioids), calcium channel blockers, GLP-1 inhibitors or tricyclic antidepressants.

Infections. Gastroparesis can occur temporarily following a viral or bacterial infection.

Auto-immune conditions. Gastroparesis is a rare complication of some auto-immune conditions such as hypothyroidism or systemic sclerosis.

Other conditions. Some neurological conditions such as multiple sclerosis, Parkinson's disease, or following a stroke, increase the risk of gastroparesis although this is not common. As a result of having an underactive thyroid gland (hypothyroidism). In a number of rare conditions such as systemic sclerosis or amyloidosis.

What are the tests for gastroparesis?

Back to contentsIf gastroparesis is suspected, a referral to a gastroenterologist (hospital specialist) will be made. One or more of the following tests may be needed:

Barium meal

During a barium meal test, a liquid containing barium is swallowed. This is then seen on an X-ray and highlights how the liquid is passing through the digestive system.

Gastric emptying scintigraphy (GES)

A solid meal (usually scrambled egg with bread) containing a small amount of a radioactive substance (called an isotope) is eaten. The isotope disappears from the body very quickly but allows the progress of the meal to be monitored, using a special external camera, to see how long it takes for the food to progress through the stomach. This test is very useful to help diagnose gastroparesis. However, an abnormal GES result does not necessarily mean that gastroparesis is the diagnosis.

Stable isotope breath test

This involves either a solid or liquid meal, which again includes a small amount of an isotope. This isotope is converted to carbon dioxide gas in the body and the amount of carbon dioxide gas is then measured in the breath. This test can show how fast the stomach empties after eating food.

Gastroscopy

In a gastroscopy, a thin, flexible tube with a tiny camera (endoscope) is passed down your throat and into the stomach to examine the stomach lining and rule out other possible causes for gastroparesis symptoms. In gastroparesis the test result is usually normal.

Ultrasound scan or MRI

Scans called ultrasound and MRI may may also be used to look for other possible causes for the symptoms.

Continue reading below

Gastroparesis treatment

Back to contentsTreatment aims to improve symptoms and to improve gastric emptying. Gastroparesis cannot usually be cured, but dietary changes and medical treatment can help to control symptoms.

Dietary advice

Eat smaller, more frequent meals.

Eat soft and liquid foods, as these are easier to digest.

Avoid tough fibrous foods, such as raw vegetables, broccoli, celery, citrus fruits, apples with their skin, oranges, pumpkin, grapes, prunes and raisins.

Chew food well before swallowing.

Drink liquids with each meal, but avoid fizzy drinks.

Avoid foods that are high in fat, which can also slow down digestion.

Following eating any meal, wait for at least two hours before lying down.

A dietician referral may be needed to advise on ensuring that the diet is adequate for nutritional needs. Occasionally oral nutrition supplements may be advised to help ensure the intake of essential nutrients and calories if unable to eat much solid food.

Improved diabetic control

Improving control of high blood sugars is very important for people who have diabetes and have been diagnosed with diabetic gastroparesis. It is also important in order to reduce the risks of developing gastroparesis. See also the separate leaflets on Type 1 diabetes and Type 2 diabetes for more information.

Medicines

Medicines can be used to help reduce gastroparesis symptoms. The medicines include:

Medications to stimulate the stomach muscles. These medications include domperidone, metoclopramide and erythromycin.

Medications to control nausea and vomiting. Drugs that help ease nausea and vomiting include ondansetron and prochlorperazine. Domperidone and metoclopramide also help to control nausea and vomiting.

Medications that work on the nerves themselves. These include anti-depressants such as mirtazapine and buproprion, anti-psychotics called levosulpiride and haloperidol, and the antibiotic, erythromycin.

Gastric electrical stimulation

If dietary changes and medicine do not help the symptoms, a treatment called gastric electrical stimulation may be recommended.

This treatment involves a minor surgical procedure to implant a battery-operated device under the skin of the abdomen. Two leads attached to this device are fixed to the muscles of the lower abdomen. They send electrical impulses to help stimulate the stomach muscles involved in controlling the passage of food. The device is turned on using a handheld external control.

The effectiveness of this treatment is very variable and it is not suitable for everyone with gastroparesis. For many people who do respond, the benefit will only last for up to 12 months. Currently, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) has decided that there is not enough evidence for gastric electrical stimulation to make it available for treatment on the NHS in the UK.

There is also a small chance that this treatment may cause complications that mean the device has to be removed. The possible complications include:

Infection.

The device dislodging and moving.

Damage to the abdominal wall.

Botulinum toxin injections

For people with severe gastroparesis, injecting botulinum toxin into the valve between the stomach and small intestine may be considered. This relaxes the valve and keeps it open for a longer period of time so that food can pass through.

The injection is given through a thin, flexible tube (endoscope) which is passed down your throat and into your stomach. The benefit of this treatment is also variable and some studies have found it may not be very effective. Most studies suggest that any benefit is very short-lived.

Surgery

Surgery may be recommended if all other treatments have not helped. These operations are designed to reduce gastroparesis symptoms by allowing food to move through the stomach more easily. The options for surgery include:

Creating an opening between the stomach and small intestine (gastroenterostomy). A small tube (stent) is used to keep this connection open.

Connecting the stomach directly to the second part of the small intestine, the jejunum (gastrojejunostomy).

Some people may benefit from having an operation to insert a tube into the stomach through the abdomen which can be opened at intervals to release gas and relieve bloating.

Feeding tube

People with extremely severe gastroparesis that is not improved with any treatment may need a feeding tube. There are many different types of temporary and permanent feeding tube.

A temporary feeding tube, called a nasojejunal tube, may be tried first. This delivers nutrients directly into the small intestine. A thin tube is passed through the nose, down the oesophagus, through the stomach and into the gut (small intestine).

A feeding tube can also be inserted into the bowel through a cut (incision) made in the abdomen. This is known as a jejunostomy. Liquid food can be delivered through the tube and straight to the bowel to be absorbed into the body without having to go through the stomach.

An alternative feeding method for severe gastroparesis is intravenous (parenteral) nutrition. This allows liquid nutrients to be delivered into the bloodstream through a catheter inserted into a large vein. This route of feeding would only be used if there is also a problem with the gut (small intestine) as well as gastroparesis.

Other treatments

Other treatments which may be considered include gastric peroral endoscopy myotomy (G-POEM). A thin tube with a camera is inserted though the mouth and passed to the stomach. A muscle in the stomach is then cut, to help the stomach empty more easily.

Gastroparesis complications

Back to contentsGastroparesis can lead to some potentially serious complications. These complications include:

Dehydration as a result of repeated vomiting.

Malnutrition, when the body is not getting enough nutrients. This can vary from mild to severe.

Unpredictable blood sugar levels in people with diabetes.

Long-term symptoms can reduce quality of life and may lead to depression.

Outcome

Back to contentsGastroparesis symptoms may improve over time (usually this takes at least 12 months) for some people, particularly those with gastroparesis after an infection.

Where gastroparesis is due to any cause other than infection, the outlook (prognosis) is more variable. However, the treatments outlined above can be very effective and so reduce symptoms and improve quality of life.

Patient picks for Other digestive conditions

Digestive health

Mallory-Weiss tear

Mallory-Weiss syndrome (also called Mallory-Weiss tear) is the name given to bleeding and other symptoms caused by a tear in the lining of the upper part of the gut (gastrointestinal tract). It is usually diagnosed by having a test called a gastroscopy (endoscopy). This involves a tube being passed down through the gullet (oesophagus) into the stomach. In many cases, the bleeding has stopped by the time gastroscopy takes place and specific treatment is not needed. The tear usually heals by itself after a few days.

by Dr Philippa Vincent, MRCGP

Digestive health

Cyclical vomiting syndrome

Cyclical vomiting syndrome is a condition which occurs mainly in children but can also affect adults. It is more common in people who have migraines. Children have severe episodes of feeling sick (nausea) and being sick (vomiting), sometimes with other symptoms. In between these episodes the person is completely well. There are various treatments available to reduce the frequency of these episodes and also to improve the symptoms when they occur.

by Dr Philippa Vincent, MRCGP

Further reading and references

- Gastroelectrical stimulation for gastroparesis; NICE Interventional procedures guidance, May 2014

- Grover M, Farrugia G, Stanghellini V; Gastroparesis: a turning point in understanding and treatment. Gut. 2019 Dec;68(12):2238-2250. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2019-318712. Epub 2019 Sep 28.

- Usai-Satta P, Bellini M, Morelli O, et al; Gastroparesis: New insights into an old disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2020 May 21;26(19):2333-2348. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v26.i19.2333.

- Gastroparesis for the nongastroenterologist; J Araujo-Duran et al

Continue reading below

Article history

The information on this page is written and peer reviewed by qualified clinicians.

Next review due: 11 Jan 2028

12 Jan 2025 | Latest version

7 Oct 2021 | Originally published

Authored by:

Dr Colin Tidy, MRCGP

Ask, share, connect.

Browse discussions, ask questions, and share experiences across hundreds of health topics.

Feeling unwell?

Assess your symptoms online for free

Sign up to the Patient newsletter

Your weekly dose of clear, trustworthy health advice - written to help you feel informed, confident and in control.

By subscribing you accept our Privacy Policy. You can unsubscribe at any time. We never sell your data.