Eye problems

Peer reviewed by Dr Colin Tidy, MRCGPLast updated by Dr Toni Hazell, MRCGPLast updated 10 Dec 2024

Meets Patient’s editorial guidelines

- DownloadDownload

- Share

- Language

- Discussion

In this series:Infective conjunctivitisAllergic conjunctivitisDry eyesEpiscleritis and scleritisUveitisSubconjunctival haemorrhage

Eye problems range from everyday irritations to serious internal conditions. This leaflet contains a list of conditions which affect the eye, grouped together by the part of the eye which is affected or involved.

In this article:

Video picks for Eye conditions

Key points

There are many eye problems that can affect different parts of the eye, from surface issues such as pink eye and dryness to deeper issues such as uveitis or scleritis.

Signs of eye problems include redness, discomfort, blurred vision, and excessive tearing.

Treatment depends on the eye problem but options may include medications, lifestyle adjustments, or surgery.

Regular eye exams, proper hygiene, protection from irritants, and managing underlying health conditions can reduce the risk of having problems with your eyes.

See the leaflet called Anatomy of the eye for details on the structure of the eye.

Continue reading below

Eye surface conditions: conjunctiva, cornea and sclera

The conjunctiva is the clear, front part of the eye overlying the white of your eye and the underside of the eyelids. Conditions of the conjunctiva do not usually directly affect vision, since the route taken by light through the pupil and into the eye does not pass through the conjunctiva.

The clear disc-shaped part of the eye over the pupil and iris is the cornea. This forms the first part of the process of focusing an image on to the back of your eye. Problems affecting the cornea therefore have the potential to affect vision. Because the cornea is very sensitive, problems affecting it are usually painful.

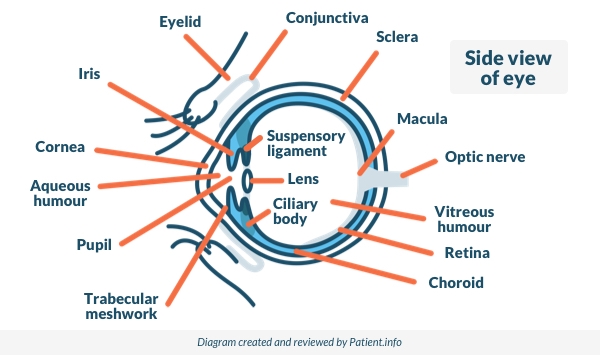

Side View of the Eye

Conjunctivitis

Conjunctivitis is inflammation or infection of the surface layer of the eye (the conjunctiva). Conjunctivitis does not normally affect the vision, other than to make things slightly blurry due to watering or discharge over the eyes.

The patient has red itchy eyes, which may be sticky if the eyes are infected. See the separate leaflets called Allergic conjunctivitis and Infective conjunctivitis for more details.

Sjögren's syndrome

Sjögren's syndrome is an autoimmune disease which most commonly causes dry eyes and mouth. It can also affect other organs including lungs, kidneys, skin and the nervous system. See the separate leaflet called Sjögren's syndrome.

Subconjunctival haemorrhage

This is a common cause of painless red eye, which looks very alarming. It is caused by a small bleed from one of the tiny blood vessels behind the conjunctiva. It can look alarming but it usually causes no symptoms and is usually harmless. Rarely, it can be associated with high blood pressure (hypertension). See the separate leaflet called Subconjunctival haemorrhage.

Episcleritis and scleritis

Episcleritis and scleritis are inflammatory conditions which affect the eye. Both cause redness but scleritis is much more serious than episcleritis. Episcleritis causes redness with discomfort and irritation but without other significant symptoms. Scleritis affects the sclera and, sometimes, the deeper tissues of the eye. See the separate leaflet called Episcleritis and scleritis.

Pterygium

A pterygium is a raised, yellowish, wedge-shaped thickening on the white part of the eye, which can occasionally spread over the cornea, obstructing vision. It is painless (although it can cause irritation, eye discomfort or dryness).

Pterygium occurs as a reaction by the eyes to being exposed to wind, dryness, dust and sunshine (solar radiation). It is particularly common in those who have lived in hot climates. It is sometimes called 'surfer's eye' or farmer's eye, as it is common in those who spend a lot of time outdoors where there are high levels of solar radiation.

It can be treated by surgery (either for cosmetic reasons or because it is starting to block vision) but often comes back; if it is not causing problems then nothing needs to be done. Sunglasses and artificial tears help prevent this.

Pinguecula

This yellow-white thickening of the sclera is common over the age of 40 years. It is caused by ultraviolet (UV) exposure, which leads to degenerative changes in the sclera. Small yellow-white deposits occur at the 3 o'clock or 9 o'clock positions on the eye. Because the surface is raised, the tear film may be interrupted, causing a loss of lubrication of the eye over the pinguecula, leading to pingueculitis.

This condition is similar to pterygium, except that only the conjunctiva is involved, and it forms a bump rather than a wedge-shaped growth. They are occasionally removed on cosmetic grounds and a pinguecula can develop into a pterygium. If it is not causing problems then nothing needs to be done.

Foreign bodies - something in your eye

If you get something in your eye then your eye will water and blink and will feel very uncomfortable. Foreign bodies which sit on the eye don't normally damage vision. However, objects which penetrate the eye and active chemicals which damage the surface (such as acids, alkalis and plaster dust) may do so, sometimes permanently.

Corneal Injury

Injury to the cornea may result in scarring, which can affect vision.

Corneal infection

Inflammation of the cornea is called keratitis and may be caused by various organisms, including germs such as bacteria and viruses. Viruses are the most common cause. See the separate leaflets called Shingles (Herpes zoster), Eye infection (Herpes simplex) and Visual problems (Blurred vision).

Autoimmune diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis, Crohn's disease and ankylosing spondylitis, may cause an inflammatory keratitis.

Allergic and inflammatory conditions of the cornea

Allergies affecting the eye may affect the cornea, with pollen as the most common allergen. Other allergens include medications, animal hair and cosmetics, such as mascara and face creams. See the separate leaflet called Allergic conjunctivitis.

Dry eyes and exposure keratitis

Dry eye syndrome (also known as keratoconjunctivitis sicca, or simply dry eyes) occurs when there is a problem with the tear film that normally keeps the eye moist and lubricated. See the separate leaflet called Dry eyes.

When the cornea dries out it may become irritated and inflamed, a condition called exposure keratitis. This can be caused by problems with tear production. Other causes include inability to close the eyelids properly, as in the facial nerve weakness seen in Bell's palsy.

Arc eye and snow blindness

Photokeratitis is sunburn of the cornea, usually noticed several hours after exposure to the sun. Snow blindness is the type of photokeratitis common in mountaineers and skiers who forget their sunglasses. Arc eye is a similar condition from exposure to the bright light of an arc lamp. See the separate leaflet called Visual problems.

Abnormalities of corneal size and shape

Keratoconus is an abnormally thin, curved cornea. It impairs vision and is treated with lenses and later contact lenses. Both help vision and protect the thinned eye surface. Corneal transplantation may be needed.

Astigmatism is a condition in which the corneal shape is slightly rugby ball-shaped rather than truly spherical, so that the focus of the eye is uneven. It is most commonly treated with corrective spectacles and contact lenses.

Corneal dystrophies

These are a group of progressive conditions which cause a build-up of cloudy material in the cornea. Most are inherited conditions, most affect both eyes and most progress only gradually. Some can affect vision, while others do not.

Continue reading below

Uveal eye conditions: iris, ciliary body and choroid

Back to contentsThe coloured part of your eye is called the iris. The iris is made up of muscle fibres which help to control the size of the pupil. The ciliary body is a small ring-like muscle that sits behind your iris and which helps the eye to focus. The choroid is the layer of tissue between your retina and your sclera, containing blood vessels and a pigment that absorbs excess light.

Anterior uveitis

Uveitis is a general term describing inflammation of the part of the eye called the uveal tract, which consists of the iris, ciliary body and choroid. Anterior uveitis is the term for inflammation which affects the front (anterior) part of the uveal tract. It is the most common type of uveitis and the most painful. See the separate leaflet called Uveitis.

Aniridia

Aniridia is the absence of the iris, usually involving both eyes. It can be genetic, present from birth or caused by an injury. Most affected people have abnormalities further inside the eye and therefore often have severe visual impairment.

Watering eyes

Watering eyes can occur at any age but are most common in young babies and in people over the age of 60. It can occur in one or both eyes. See the separate leaflet called Watering eyes (Epiphora).

Iris heterochromia and anisocoria

Heterochromia is the term used when a person's two irises are different colours, sometimes partially and sometimes completely. It can be a lifelong condition due to the person's genetic makeup. However, it can also be caused by the use (in just one eye) of certain medications which affect eye colour, or can be the result of injury to the iris.

Iris heterochromia is easily confused with anisocoria. In anisocoria one pupil does not react to light in the same way as the other one, so that the pupils are of unequal sizes and the eye with the bigger pupil appears darker.

Eye fluid and drainage conditions: the ciliary body and trabecular meshwork

Back to contentsThe ciliary body is a part of the eye which includes the following:

The ciliary muscle (which changes the shape of the pupil by changing the shape of the iris).

The ciliary epithelium, which produces aqueous humour. This is the liquid that fills the front of the eye. Aqueous humour is made continuously. It circulates through the front part of the eye and then drains away through an area called the trabecular meshwork, near the base of the iris.

Problems with the production and drainage of the fluid in the eye can lead to an increase in the pressure inside the eye (called hydrostatic pressure) and to various types of glaucoma. The underlying reason for the development of the problem is usually unclear. However, inflammatory eye conditions, eye injuries and steroid medication are amongst the known causes.

Acute angle-closure glaucoma (AACG)

AACG (often just called acute glaucoma) occurs when the flow of aqueous humour out of the eye through the trabecular meshwork is blocked. Pressure inside the eye then becomes too high very quickly. If it is not treated quickly, it can lead to permanent loss of vision. See the separate leaflet called Acute angle-closure glaucoma.

Chronic open-angle glaucoma (COAG)

COAG (often just called glaucoma) occurs when there is a partial blockage within the trabecular meshwork. This restricts drainage and leads to a build-up of pressure. The increased pressure in the eye can damage eye nerve fibres and may affect vision. See the separate leaflet called Chronic open-angle glaucoma.

Ocular hypertension

In both types of glaucoma the pressure in the eye is increased. In AACG this causes pain and loss of vision. In COAG it causes no pain and a gradual loss of vision. However, the pressure in the eyeball is raised in both conditions.

Ocular hypertension is a condition in which the pressure in the eyeball is raised but pain and gradual loss of vision do not occur. Ocular hypertension affects around 5 in 100 people over the age of 40 years. However, most do not go on to develop the vision changes of glaucoma (although their risk of developing it is increased). It may be that the nerves in the eyes of people who develop glaucoma are more sensitive to pressure than the nerves in the eyes of those who do not.

Normal-tension glaucoma

This is almost the opposite condition to ocular hypertension. In normal-tension glaucoma the pressure in the eyes is not raised above what eye specialists consider normal. However, damage to the nerves of the eye typical of glaucoma nevertheless occurs.

The cause is uncertain, but it is believed that in these patients the nerves of the eye are particularly sensitive to pressure changes. These nerves can therefore be damaged even at pressures which are not considered harmful in most people.

Continue reading below

Lens and focusing conditions

Back to contentsThe lens can change shape with the help of the ciliary body which contains fine muscle fibres that pull on it. Depending on the angle of the light coming into it, the lens becomes more or less curved (convex). This alters its strength and allows it to focus the light correctly on to the back of the eye.

Refractive errors

Problems with focusing may mean that you need to wear glasses or contact lenses in order to see clearly. There are four main types of refractive error:

Short sight (myopia). See the separate leaflet called Myopia.

Long sight (hypermetropia). See the separate leaflet called Hypermetropia.

A refractive error due to an unevenly curved cornea (a condition known as astigmatism). See the separate leaflet called Astigmatism.

Age-related long sight (presbyopia). See the separate leaflet called Presbyopia.

Refractive errors are generally dealt with by an optician, rather than a doctor, so a visit to the GP isn't usually appropriate.

Cataract

A cataract is a condition in which the lens of an eye becomes cloudy and affects vision. Most commonly, cataracts occur in older people and develop gradually. Initially there may be little or no effect on the vision. See the separate leaflet called Cataracts.

Lens dislocation (ectopia lentis)

Ectopia lentis is the partial or complete displacement of the lens away from its normal position. It may occur after trauma (the most common cause - usually a direct blow to the eye, eye socket or head). Alternatively, it can result from eye disease or disease affecting the whole body (systemic disease). As well as affecting vision the condition can cause glaucoma (see above).

Eye diseases associated with ectopia lentis include Marfan's syndrome. In about half of people with Marfan's syndrome, the lens is dislocated at birth or it dislocates before adulthood. People with Marfan's syndrome are also more prone to retinal detachment (see below), short-sightedness and cataracts. See the separate leaflet called Marfan's syndrome.

Posterior chamber eye conditions: the vitreous

Back to contentsThe globe of the eye needs to keep its shape so that light rays are focused accurately on to the retina. The posterior part the eye is therefore filled with a jelly-like substance called the vitreous humour (or sometimes, the vitreous body or just the vitreous).

It consists mainly of water, with some protein (collagen), hyaluronic acid and salt. It helps to keep the retina in place by pushing it against the choroid. It is lightly attached to the retina posteriorly.

Posterior uveitis and other forms of uveitis

Uveitis is inflammation of the tissues of the eye. It can be described as anterior, posterior or intermediate uveitis, or panuveitis. See the separate leaflet called Uveitis.

Vitreous haemorrhage

Vitreous haemorrhage occurs when blood leaks into the vitreous humour inside the eye, most commonly from blood vessels at the back of the eye. If the vitreous humour is clouded or filled with blood, vision will be impaired. This varies from a few 'floaters' and cloudiness of the vision through to the vision going completely dark. See the separate leaflet called Vitreous haemorrhage.

Posterior vitreous detachment

The vitreous is lightly attached to the retina at the back by protein fibres. As we age, the vitreous shrinks and eventually tends to pull away from the retina and cause a vitreous detachment. The vitreous is already detached in about 75% of people aged over 65 years. Many will not have been aware of it.

However, if symptoms occur they are light flashes and floaters (dots, spots or wispy lace objects floating across the vision), which can also be symptoms of retinal detachment. The flashes tend to settle once the detachment is complete. See the separate leaflet called Flashes, floaters and haloes.

Back of the eye conditions: the retina and optic nerve

Back to contentsThe retina is a layer on the inside of the back of the eyeball. It contains highly specialised nerve cells. These convert the light which is focused there into electrical signals. These are then passed through the optic nerves to the parts of the brain which process vision and build up the picture that we see.

Near the centre of the retina is the macula. The macula is a small highly sensitive part of the retina. It is responsible for detailed central vision, the part you use when you look directly at something. It contains the fovea, the area of your eye which produces the sharpest images of all.

Retinal detachment (RD)

The retina is made up of two layers: an inner layer of light-sensitive 'seeing cells' (called rods and cones) and an outer layer of pigmented cells which nourish and support them. RD occurs when the inner layer of rods and cones is separated from the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE). Symptoms include flashing lights, 'floaters' and loss of vision. Retinal detachment is a medical emergency. See the separate leaflet called Retinal detachment.

Macular degeneration

The macula is the small area of the retina at the back of your eye and responsible for your central vision. Age-related macular degeneration (AMD, or ARMD) is the most common cause of severe sight problems in the developed world. It causes a gradual loss of central vision. See the separate leaflet called Age-related macular degeneration

'Colour blindness' (colour vision deficiency)

Colour vision deficiency means you are unable to see certain colours. It is usually an inherited (genetic) disorder and you have it from birth. Red-green colour vision deficiency is the most common form. The condition can be variable from mild to severe. Some patients have no colour vision at all (achromatopsia). See the separate leaflet called Colour vision deficiency (Colour blindness).

Retinitis pigmentosa

Retinitis pigmentosa is the term for several inherited diseases with a gradual deterioration of the light-sensitive cells of the retina. Symptoms often start in childhood with difficulty seeing in the dark. See the separate leaflet called Visual problems.

Retinal dystrophy

Retinal dystrophies are a group of inherited disorders which result in changes to the retina, which may affect vision; some people with this condition will become blind in their 30s, whereas others will retain vision into old age. See the separate leaflet called Visual problems.

Charles Bonnet syndrome (CBS)

CBS affects people who have experienced a sharp decline in their vision. CBS involves visual hallucinations. These seem to occur as the brain stops receiving information from the retina and starts to replace it with information from our own memory stores. See the separate leaflet called Charles Bonnet syndrome.

Optic neuritis

Optic neuritis is caused by inflammation of the optic nerve in the eye. It can involve one or both eyes and it can be recurrent. It is painful, particularly on eye movements. It can cause blurred vision or loss of colour vision. See the separate leaflet called Visual problems.

Optic neuritis can sometimes be the first sign of multiple sclerosis (MS), a disorder of the brain and spinal cord. Optic neuritis is the first symptom of MS for around one in four people with MS. However, not all optic neuritis is due to MS. See the separate leaflet called Multiple sclerosis.

Retinal vein occlusion

Retinal vein occlusion occurs when one of the tiny retinal veins becomes blocked by a blood clot. It usually leads to a painless decrease in vision in one eye. See the separate leaflet called Retinal vein occlusion.

Retinal artery occlusion

Retinal artery occlusion is a blockage of all or part of the blood supply to the retina because the retinal artery is blocked by a blood clot. Occasionally both eyes are affected but this occurs in fewer than 2 in 100 cases.

Tumours of the eye and optic nerve

Tumours in the eye principally occur in the middle and inner layers of the eye, particularly the retina and optic nerve. They are rare. However, they include melanoma (which typically affects the choroid layer and is usually a tumour of later life) and retinoblastoma.

Choroidal melanoma

Choroidal melanoma arises from pigment cells in the choroid layer. It is the most common primary malignant eye tumour in adults. 98% of all cases occur in ethnically white races. Most often it has symptoms which don't show (it is asymptomatic) and is found on chance examination. It can occasionally cause visual loss or vitreous haemorrhage. The majority of patients are over 50 years of age.

Retinoblastoma

Retinoblastoma is the commonest cancerous (malignant) tumour of the eye. It accounts for 3% of all childhood cancers. Onset generally occurs between the third month of pregnancy and 4 years of age with very few diagnosed later than 5 years of age. Most cases affect one eye only. The most common signs are leukocoria (a white pupil noticed on flash photography or in dim lighting) and squint (strabismus). The management of retinoblastoma has improved tremendously and it is now a largely curable disease.

Chorioretinitis

Chorioretinitis is infection or inflammation of the choroid and retina. The choroid is the pigmented, highly vascular layer of the globe of the eye whose main function is to nourish the outer layers of the retina. The effect on vision depends on the location and size of the damaged area. See the separate leaflet called Visual problems.

Retinopathy

The term retinopathy covers various disorders of the retina that can affect vision. Retinopathy is usually due to damage to the tiny blood vessels in the retina. This leads to oxygen shortage followed by the growth of tiny new blood vessels in a disorderly way, often into the eye. These can bleed and the retina may be permanently damaged.

Retinopathy is commonly caused by diabetes but is sometimes caused by other diseases such as very high blood pressure (hypertension). See the separate leaflets called Diabetic retinopathy and High blood pressure (Hypertension).

Another form of retinopathy is that seen in very premature babies (under 32 weeks of gestation) who require oxygen therapy. It is the leading cause of preventable childhood visual impairment in the developed world.

Optic atrophy

Optic atrophy is the loss of some or all of the nerve fibres in the optic nerve. It causes reduction in vision or loss of vision. This may be central vision or edge vision or both, depending on which fibres are lost.

Optic atrophy is the end result of many conditions which can damage the optic nerve. These include glaucoma, head injury, retinal vein occlusion, retinal artery occlusion and MS. However, it can also happen alone without obvious cause. Some cases may be inherited.

Whole eye conditions

Back to contentsThyroid eye disease

In thyroid eye disease the muscles and fatty tissues within the eye socket (orbit) become inflamed and swollen. This results in the eyeball being pushed forward, affecting the movements of the eye. In severe cases vision may be affected. See the separate leaflet called Thyroid eye disease.

Albinism

Albinism covers a group of inherited disorders in which there is shortage of melanin production. Melanin is the pigment that gives colour to our skin, hair and eyes. Visual problems are an important part of albinism. Melanin is reduced or absent where it is normally present in the eye, skin, hair and brain. This causes abnormal development of the nerve pathways needed for vision.

Severe nystagmus (jumping of the eyes, usually from side to side), light sensitivity, squint and reduced vision are common features. Contrary to common belief, the irises of patients with albinism are not pink. Instead it varies from a dull grey to blue and even brown (brown is common in ethnic groups with darker pigmentation).

Under certain lighting conditions there is a reddish or violet hue reflected through the iris from the retina and the eyes can appear red. Not all types of albinism result in very pale skin and hair.

Coloboma

Coloboma is a defect or gap in the tissues of the eye, occurring during development in the womb. It can involve one or more of several parts of the eye, including the eyelid, cornea, iris, ciliary body, lens, retina, choroid and optic disc.

Coloboma is a rare condition and is sometimes associated with abnormally small eyes (microphthalmia). Not all colobomata affect vision. However, the condition is an important cause of childhood visual impairment. Worldwide, it causes around 1 in 20 cases of severe visual impairment in childhood.

Eye movement conditions

Back to contentsSquint (strabismus)

Strabismus is a condition where the eyes do not look in the same direction. Whilst one eye looks forwards to focus on an object, the other eye turns either inwards, outwards, upwards or downwards. Most squints occur in young children. See the separate leaflet called Squint in children (Strabismus).

Nystagmus

Nystagmus is a symptom, rather than a diagnosis, in which there is a repetitive to-and-fro oscillation of the eyes outside the person's control. It usually affects both eyes, with one worse than the other.

Most nystagmus is present from an early age and is caused by abnormalities of visual development in childhood. This leads to sensory deprivation of the retina. Nystagmus which comes on after childhood is more often due to diseases of the balance organs. These include labyrinthitis and disorders of the brain such as MS, diabetic neuropathy and brain tumours.

Nystagmus is involuntary, meaning people with the condition cannot control their eyes. It improves slightly as a person reaches adulthood but worsens with tiredness and stress. Most people with nystagmus have visual difficulties because the eyes continually sweep over what they are viewing, making it impossible to obtain a clear image.

To see better, patients may turn their head and lock their eyes into what's called the 'null point'. This describes the head angle that makes the eyes move the least, to attempt to stabilise what they see. Nystagmus can occur as a short-term sign, for example in some conditions that cause a type of dizziness called vertigo.

Eyelid conditions

Back to contentsChalazion

A chalazion is a small (2-8 mm) fluid-filled swelling (cyst) in the eyelid. It is common and sometimes called a meibomian cyst or tarsal cyst. A chalazion is more common on the upper eyelid and can affect both eyes. It is not the same as a stye. See the separate leaflet called Chalazion.

Stye

A stye is a common painful eyelid problem, where a small infection forms at the base of an eyelash. It looks like a small yellow pus-filled spot. Vision is unaffected. See the separate leaflet called Stye.

Ectropion and entropion

When part or all of the lower eyelid turns outwards away from the eye, the condition is known as an ectropion. An entropion occurs where the eyelid turns towards the eye, causing the eyelashes to rub against the front of the eye (cornea). See the separate leaflets called Ectropion and Entropion.

Lagophthalmos

Lagophthalmos is the inability to close the eyelids completely. This leads to corneal exposure and dryness. The main cause is facial nerve paralysis. However, it can occur after trauma or eyelid surgery (cicatricial lagophthalmos) or during sleep (nocturnal lagophthalmos). The main cause is Bell's palsy.

Bell's palsy

Bell's palsy is the most common cause of sudden facial weakness (paralysis). It is due to a problem with the facial nerve. It may cause a watery or dry eye that will not close properly. See the separate leaflet called Bell's palsy.

Drooping eyelids

Drooping of the eyelid is called ptosis by doctors. It may affect one or both lids and there are many causes. People may comment that you look sleepy or tired.

Ptosis

Ptosis can be due to long-term contact lens wear, to eye trauma or surgery, or to simple ageing of the muscles of the eyelid. Less common causes of ptosis include diseases causing muscle weakness (such as myasthenia gravis and myotonic dystrophy) and conditions affecting the nerves to the eyelid.

Floppy eyelid syndrome

Floppy eyelid syndrome is a specific condition which tends to occur in obese men and is often associated with sleep apnoea and snoring. The loose lids tend to come apart during sleep, resulting in an exposed cornea.

Blepharitis

Blepharitis means inflammation of the eyelids. It causes the eyes to feel sore and gritty. It can be a troublesome and recurring condition with no one-off cure. It can be associated with other skin conditions such as rosacea and seborrhoeic dermatitis. See the separate leaflet called Blepharitis.

Disorders affecting the eyelashes

There are many conditions which can affect the growth and appearance of eyelashes:

Trichiasis is a problem of the lid edge in which the eyelashes are misdirected and in contact with the eye (ocular) surface. It is usually caused by scarring of the eyelash follicles.

Poliosis is premature, localised whitening of the lashes and eyebrows.

Madarosis is loss of eyebrows or eyelashes. It is common and occurs in association with conditions affecting the whole body (systemic conditions) and with localised conditions. These include:

An overactive thyroid gland (hyperthyroidism).

An underactive thyroid gland (hypothyroidism).

Autoimmune disease.

Normal ageing.

Eyelid infections.

Some medicines.

General conditions which affect the eye

Back to contentsMany conditions which have their main effects elsewhere in the body can affect the eye, although they do not always do so. They include:

Diabetes mellitus - may cause diabetic retinopathy.

High blood pressure (hypertension) - may cause hypertensive retinopathy.

A condition in which too much growth hormone is made (acromegaly) - may cause optic atrophy.

Inflammatory disorders - those disorders which particularly affect joints can also inflame the eye, causing scleritis or uveitis. These include:

Rheumatoid arthritis - may cause episcleritis, scleritis and dry eyes.

Systemic lupus erythematosus - may cause dry eyes, keratitis and scleritis, retinal vasculitis or optic neuropathy.

Ankylosing spondylitis - commonly causes anterior uveitis iritis.

Reactive arthritis - may cause conjunctivitis and uveitis.

Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis - may cause uveitis, keratitis, dry eyes and episcleritis.

Sarcoidosis - may cause conjunctival inflammation and posterior uveitis.

Systemic sclerosis - may cause eyelid tightening.

Psoriatic arthritis - may cause uveitis, conjunctivitis, keratitis or dry eyes.

HIV/AIDS - many eye problems can occur in AIDS, including severe infections, uveitis, retinopathy, chorioretinitis and abnormalities of the pupil.

Gilbert's syndrome - this is a condition where the liver does not process bilirubin very well. It is usually harmless, although it can occasionally cause yellowing of your skin and of the whites of your eyes (jaundice).

Vitamin A deficiency - vitamin A is important for healthy eyes. Severe deficiency may cause night blindness, corneal thinning and dryness and even retinal damage.

Frequently asked questions

Back to contentsWhat are the four most common eye problems?

The four most common eye problems are short-sightedness (myopia), long-sightedness (hyperopia), astigmatism, and presbyopia. These conditions affect how clearly you see and often require glasses or contact lenses to correct vision.

What is the most serious symptom with the eye?

The most serious eye symptoms include sudden vision loss, severe pain, flashes of light, or a sudden increase in floaters. These may indicate urgent conditions such as retinal detachment, acute glaucoma, or eye infection and require immediate medical attention.

Dr Mary Lowth is an author or the original author of this leaflet.

Patient picks for Eye conditions

Eye health

Retinal artery occlusion

Retinal artery occlusion occurs when the retinal artery or one of its branches becomes blocked. This cuts off the blood and nutrient supply to the nerve layer of the retina, leading to permanent damage. It is a common cause of sudden loss of vision in one eye, which occurs over a few seconds. The loss is usually severe. Occasionally both eyes are affected but this is rare. The condition is an emergency, as very early treatment is needed if there is to be a chance of restoring your sight.

by Dr Mary Elisabeth Lowth, FRCGP

Eye health

Eye floaters, flashes and haloes

Eye floaters and flashes are common and are usually nothing to worry about. They usually occur because of normal changes that happen in the jelly-like substance inside the eye (vitreous humour) as you age. Haloes are bright circles around a source of light. They are also referred to as glare. They are a common symptom, particularly in older people. They can sometimes be a sign of underlying eye conditions such as glaucoma.

by Dr Philippa Vincent, MRCGP

Further reading and references

- Asbell P, Messmer E, Chan C, et al; Defining the needs and preferences of patients with dry eye disease. BMJ Open Ophthalmol. 2019 Dec 5;4(1):e000315. doi: 10.1136/bmjophth-2019-000315. eCollection 2019.

- Valikodath NG, Newman-Casey PA, Lee PP, et al; Agreement of Ocular Symptom Reporting Between Patient-Reported Outcomes and Medical Records. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2017 Mar 1;135(3):225-231. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2016.5551.

Continue reading below

Article history

The information on this page is written and peer reviewed by qualified clinicians.

Next review due: 9 Dec 2027

10 Dec 2024 | Latest version

Ask, share, connect.

Browse discussions, ask questions, and share experiences across hundreds of health topics.

Feeling unwell?

Assess your symptoms online for free

Sign up to the Patient newsletter

Your weekly dose of clear, trustworthy health advice - written to help you feel informed, confident and in control.

By subscribing you accept our Privacy Policy. You can unsubscribe at any time. We never sell your data.